When most people today hear the word “virtue,” they usually don’t think “manliness.” Having virtue or being virtuous is looked at as being sissy or effeminate. In fact, we sometimes use the word in today’s vernacular to describe a woman’ssexual conduct.

However, virtue is far from being sissy or effeminate. The word “virtue” is actually rooted in “manliness.” “Virtue” comes from the Latin virtus, which in turn is derived from vir, Latin for “manliness.” Cicero, a famous Roman statesman and writer, enumerated the cardinal virtues that every man should try to live up to. They included justice, prudence, courage, and temperance. In order to have honor, a Roman man had to live each of the four virtues. When Aristotle encouraged men in the ancient world to live “the virtuous life,” it was really a call to man up.

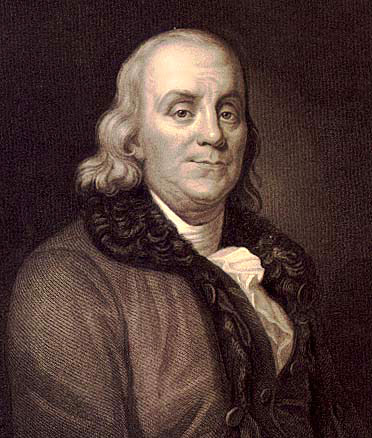

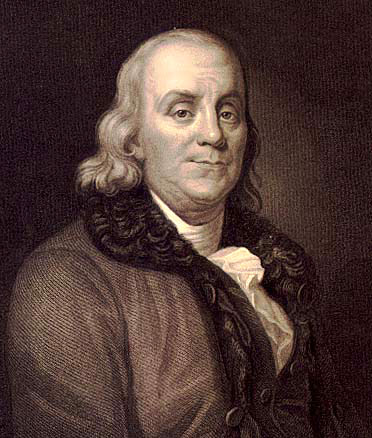

One man took up Aristotle’s challenge to live the virtuous or manly life with particular fervor: Benjamin Franklin.

Franklin’s Quest for Moral Perfection

Benjamin Franklin is an American legend. He single handily invented the idea of the “self-made man.” Despite being born into a poor family and only receiving two years of formal schooling, Franklin became a successful printer, scientist, musician, and author. Oh, and in his spare time he helped found a country, and then serve as its diplomat.

The key to Franklin’s success was his drive to constantly improve himself and accomplish his ambitions. In 1726, at the age of 20, Ben Franklin set his loftiest goal: the attainment of moral perfection.

I conceiv’d the bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection. I wish’d to live without committing any fault at any time; I would conquer all that either natural inclination, custom, or company might lead me into.

In order to accomplish his goal, Franklin developed and committed himself to a personal improvement program that consisted of living 13 virtues. The 13 virtues were:

- “TEMPERANCE. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.”

- “SILENCE. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.”

- “ORDER. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.”

- “RESOLUTION. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.”

- “FRUGALITY. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.”

- “INDUSTRY. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.”

- “SINCERITY. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.”

- “JUSTICE. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.”

- “MODERATION. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.”

- “CLEANLINESS. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation.”

- “TRANQUILLITY. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.”

- “CHASTITY. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.”

- “HUMILITY. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.”

In order to keep track of his adherence to these virtues, Franklin carried around a small book of 13 charts. The charts consisted of a column for each day of the week and 13 rows marked with the first letter of his 13 virtues. Franklin evaluated himself at the end of each day. He placed a dot next to each virtue each had violated. The goal was to minimize the number of marks, thus indicating a “clean” life free of vice.

In order to keep track of his adherence to these virtues, Franklin carried around a small book of 13 charts. The charts consisted of a column for each day of the week and 13 rows marked with the first letter of his 13 virtues. Franklin evaluated himself at the end of each day. He placed a dot next to each virtue each had violated. The goal was to minimize the number of marks, thus indicating a “clean” life free of vice.

Franklin would especially focus on one virtue each week by placing that virtue at the top that week’s chart and including a “short precept” to explain its meaning. Thus, after 13 weeks he had moved through all 13 virtues and would then start the process over again.

When Franklin first started out on his program he found himself putting marks in the book more than he wanted to. But as time went by, he saw the marks diminish.

While Franklin never accomplished his goal of moral perfection, and had some notable flaws (womanizing and his love of beer probably gave him problems with chastity and temperance), he felt he benefited from the attempt at it.

Tho’ I never arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was, by the endeavour, a better and a happier man than I otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it.

Applying Franklin’s pursuit of “the virtuous life” in your life

Here are The Art of Manliness we want to resurrect the idea that being manly means being virtuous. We think old Ben Franklin can show us a thing or two on how best to live a virtuous (or manly) life.

In order to help you live the virtuous life, we’re going to highlight one of Ben’s virtues that you can focus on throughout the week. We’ll find a great man from history that exemplified that virtue and extract practical lessons from them that can help us live that virtue more fully. When we get done with Franklin’s virtues, we’ll add some more.

Until then, why not get started on the project by picking up one of our Franklin’s Virtues Journal?

Read the Rest of the 13 Virtues Series

- Temperance

- Silence

- Order

- Resolution

- Industry

- Sincerity

- Justice

- Moderation

- Cleanliness

- Tranquility

- Chastity

- Humility

Sources