When most modern men shave or comb their hair, it’s just something they do to get ready for the day. Sure, you might make the experience a bit more enjoyable by using a straight razor or an old-school pomade, but other than that you probably don’t give grooming much thought.

But throughout time and across cultures, shaving, beard trimming, and even hairstyling carried heavy cultural meaning for men. Shaving and grooming were part of many cultures’ rites of passage, were sometimes tied to religious rituals, and could connote power or status.

Today we explore some of the unique cultural and religious meanings of shaving and men’s grooming from history and around the world. If you think today’s man is overly fastidious about his appearance, wait until you get a load of the practices of our manly ancestors.

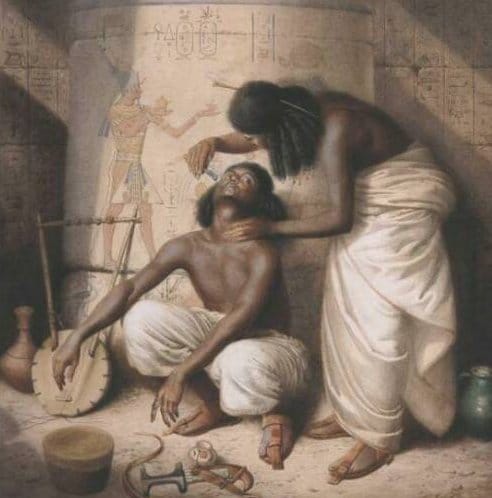

Ancient Egyptians

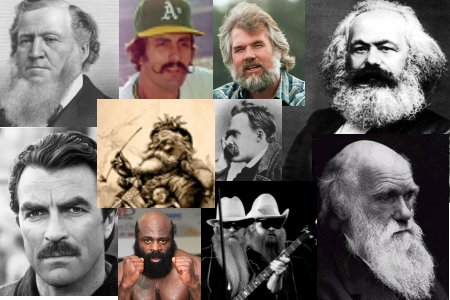

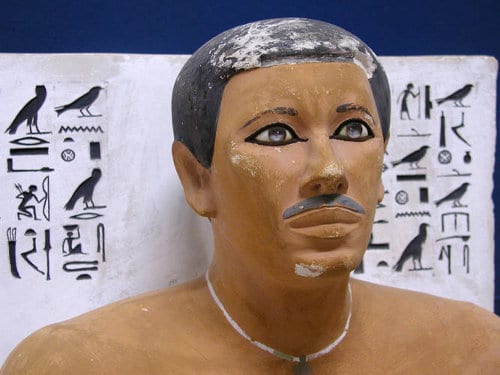

In the early years of Egyptian civilization, men grew out their beards along with the hair on their heads. Death masks and murals from this period depict men sporting full beards. Kings would braid their beards and dust them with gold powder. Some Egyptian men, like Rahotep, a Third Dynasty official, even rocked awesome mustaches.

Rahotep: Government official and winner of seven gold medals in the Egyptian Olympics.

But the love of virile and natural body hair would quickly fade as Egyptian men embraced shaving with gusto at the start of the Dynastic Period. During this time, hair became seen as a symbol of man’s animalistic tendencies. Thus to put off the primal man and become civilized, Egyptian men began removing all the hair from their heads, faces, and even bodies. Wealthy Egyptian men often hired full-time barbers to live with them in order to maintain their smooth as a baby’s behind look every day. Less affluent Egyptians would frequent the local barber to have their faces and heads shaved daily. To appear unshaven became a mark of low social status.

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Egyptian priests in 6th century BCE would shave their entire bodies every other day as part of a ritual cleansing. They even plucked out all of their eyebrows and even their eyelashes (ouch!).

Hair removal was so important to Ancient Egyptians that kings would have their barbers shave them with sanctified, jewel-encrusted razors. When a king died, he was often buried with a barber and his trusty razor, so he could continue to get his daily shaves in the afterlife.

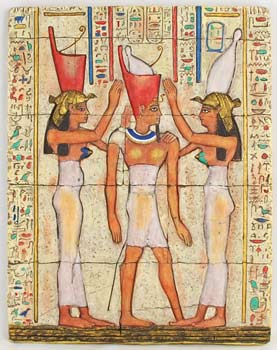

While Dynastic Egyptians eschewed facial hair, they still reverenced the beard as a symbol of divinity and power. Kings during this period were often depicted sporting beards. But rather than embracing the full-on natural beard like their predecessors in the Old and Middle Kingdoms, Dynastic kings sported a small fake goatee called the “osird,” or “the divine beard.” The osird was usually made of precious metals like gold or silver and was worn during religious rites or celebrations. While living, a king’s osird was straight. When he died, an upward pointed curl would be added at the end, denoting that the pharaoh had become a god.

Ancient Mesopotamians

An eye for an eye, a beard hair for a beard hair…

Ancient men living between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers devoted a lot of time and attention to the care of their beards. The Assyrians, Sumerians, and Phoenicians all grew long, thick, and luxurious beards. None of that fake Egyptian beard stuff for these gents. Upper-class men dyed their beards with henna and powdered them with gold-dust. Ribbons and thread were woven throughout their beards for added flair. The most distinct feature of Mesopotamian beards was the way in which they were meticulously and artfully curled. Men would spend hours having the ends of their beards curled into tiny locks and arranged in three hanging tiers. The higher up you were in Mesopotamian hierarchy, the longer and more elaborate your beard was.

Ancient Mesopotamians also spent a lot of time thinking about the hair on their heads. While they weren’t fond of hair washing (most only washed their hair once a year), they did devise an elaborate hairstyle system to signify what sort of work a man did. Doctors, lawyers, priests, and even slaves had their own special kind of haircut. Whenever a Mesopotamian man was at party making small talk, he could simply point at his head whenever someone asked, “So Belanum, what do you do for a living?”

The Ancient Greeks

Ancient Greek philosophy would have likely been greatly impoverished if the period’s philosophers had not had a nice beard to stroke while contemplating the universe.

The Ancient Greeks were a people of the beard. For them, a beard was a sign of virility, manhood, and wisdom. In fact, according to Plutarch, when an ancient Greek boy began growing whiskers, it was the custom to dedicate the boy’s first beard to the sun god Apollo in a religious ritual. Greek boys were also not allowed to cut the hair on their heads until their beards started to grow.

Greek men would only cut their beards during times of grief and mourning. If a blade wasn’t available, a grief-stricken man would resort to tearing out his beard with his bare hands or burning it off with fire. When a man died, his relatives would often hang the trimmings of his beard on the door.

Cutting another man’s beard was a serious offense and punishable by a fine and sometimes even jail. Being de-bearded was considered shameful, and thus the ancient Greeks would often use beard cutting as a means of punishment. For example, the Spartans would shave off half of a man’s beard to indicate he had displayed cowardice during battle.

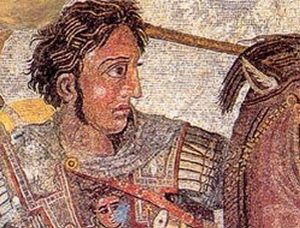

Alexander the Great started the trend towards whisker-less warriors.

Beard growing would eventually go out of style among the ancient Greeks when Alexander the Great came to power. Xander, ever the tactician, ordered his soldiers to remove their beards lest they be grabbed by their enemies in hand-to-hand combat.

The Ancient Romans

To distinguish themselves from their Greek cousins, the Ancient Romans were clean-shaven folk. A young man’s first shave was an important event in his life and was ritualized in an elaborate religious ceremony. Young men would keep growing their peach fuzz until they reached the age of majority. On their birthday, they would shave while family and friends watched. The whiskers would then be placed in a special box and consecrated to a Roman deity. For example, the Emperor Nero housed his first shavings in a golden, pearl-studded casket. Some young men would rub olive oil on their faces throughout their teenage years in the hopes it would help them grow a thick beard for their ceremonial first shave. In addition to keeping their first whiskers in consecrated boxes, the Roman grammarian Sextus Pompeius Festus recorded that young Roman men would shave their first full-on beard and hang it from a communal capillaris arbor, or tree of hair.

Ancient Germanic Tribes

Ancient Germanic men would make oaths by swearing on their beard.

In the German frontiers of ancient Rome lived barbarian tribes who grew some of the fiercest beards in history. The mostly beardless ancient Romans were both afraid of and fascinated by Germanic beards.

We learn from the Roman historian Tacitus that it was customary for a young Germanic man to make a vow to never cut his hair or beard until he had killed an enemy. Later Germanic tribes had a similar beard vow. St. Gregory of Tours notes in his History that the defeated Saxons vowed to never cut their hair or beards until they were avenged. Unfortunately, the beards weren’t able to help them, as they were summarily defeated again.

Ancient Hindus

While beard-growing was the norm for many Hindu sects, some practiced a first shave ritual similar to the ancient Romans. According to the Grihya Sutra, a collection of ritual texts that outlined the rites a Hindu was to perform in his home, a boy was to receive his first shave when he turned sixteen. Known as the Godanakaruman, this ceremonial first shave was performed by a local barber. The face as well as the head were to be razored clean.

The Grihya Sutra laid out the fees a family was to pay the barber for their boy’s first shave: an ox and cow if you were Brahmin, a pair of horses if you were a Kshatriya, or two sheep if you were Vaishya. Before the shave, the family would gather around the boy and the barber and repeat the following mantra: Purify his head and face, O barber, but do not take away his life. Basically, it was an admonishment to the barber to give the boy a close shave, but to not go all Sweeney Todd on him.

African Tribes

Amongst African tribes, both past and present, male grooming practices are as varied as the many tribes that inhabit that continent.

In Kenya’s Masai tribe for example, the young men have their heads shaved as part of the numerous steps of initiation into manhood they must undergo. When a Masai boy is circumcised around age 14, he becomes a warrior in the tribe. Ten years later, another ceremony is held to initiate him as a senior warrior. At this ceremony, his mother shaves his head while he sits on the same cowhide on which he was circumcised a decade earlier. The Masai warrior can now take a wife. Two initiation ceremonies later, a Masai man ends his journey into manhood and becomes a junior elder of the tribe. During this ceremony he is given an elder chair by the tribe, which he will keep his whole life through. He sits in the chair and his wife shaves his head to once again symbolize his new status.

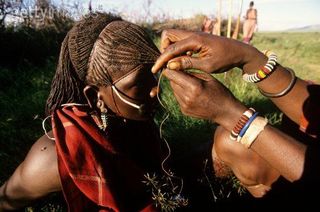

Masai men spend hours doing each other’s hair.

Masai warriors are the only group in the tribe allowed to wear their hair long (women shave their heads), and the young men allow their hair to grow out in-between the periodic initiatory shavings. Thus it is the men of the tribe who are most concerned about their tresses, and they spend hours grooming and styling each other’s hair — mixing in ashes, clay, and animal fat, coloring it with ochre, and forming thinly braided strands which may be woven together with cotton or wool threads. The warriors’ “manes” symbolize the African lion’s strength and masculine beauty, and is a source of pride and confidence.

Early Christians

While the ancient Jews and Muslims were commanded not to shave off their beards, the acceptability of beards among the early Christians waxed and waned.

Sometimes beards were seen as symbols of piety — other times as diabolic. In the faith’s early days, the beard took on the former meaning. A man who decided to devote himself to a monastic life would often undergo an initiatory first shave (in addition to the tonsure — the cutting of the hair on the crown of the head) that was observed by the other monks in the monastery. Before the shave, a prayer called the benedictio ad barbam, or “blessing of the beard” would be said. One version used in the Abbey of Bec in France went like this:

Dominus vobiscum.

Oremus, Dilectissimi, Deum Patrem omnipotentem, ut huic Famulo suo N., quem ad juvenitem perducere est aetatem, bendictionis suae dona concedate; ut, sicut exemplo Beati Petri, Principis Apostolorum, ei exteriora, pro Christi amore, sunt attondenda juventutis auspicia, ita praecordiorum divellantur interiorum superflua, ac felicitatis aetermae percipiat incrementa. Per eum qui unus in Trinitate perfecta vivit et gloriatur Deus per imortalia saecula saeculorum. Amen

My Latin is a little rusty, but I believe the prayer says a new cleric must follow the example of the apostle Peter by shaving, which makes sense if you know the story of how Peter’s life came to an end. According to non-canonical Church history, before he was crucified upside down, Peter was mocked by having his head and beard shaved. So a young initiate in the Abbey of Bec symbolically shared Peter’s mockery by having his head and face shaved, too. After the shaving, the hair and whiskers were consecrated on an altar.

After their initial shave, monks were put on a strict shaving schedule. In a convocation held in 817 AD, French monks decided that they should shave once a fortnight, but would take part in an occasional razor and shaving fast during certain times of the year.

Listen to our podcast with William Ayot about man’s need for ritual, in all its forms: