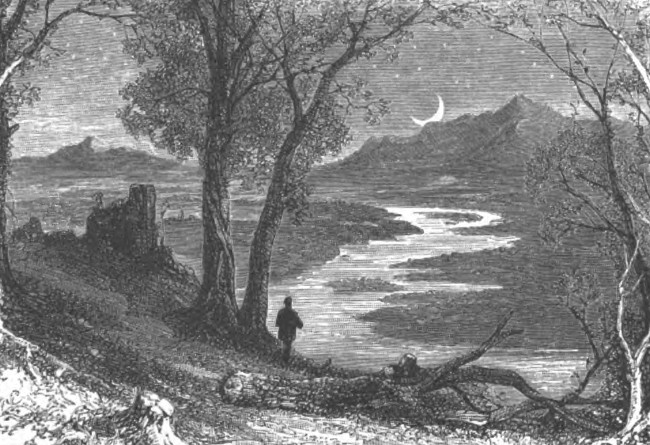

Whether you’re hunting wild boar at night, taking a moonlit walk through the woods, running some kind of covert operation, or simply trying to find the bathroom in an unfamiliar house or hotel, it can be advantageous to be able to see well in the dark.

You could fire up a flashlight to accomplish that purpose, but that has its disadvantages, including letting the thing you’re hunting know where you are, and, ironically, actually diminishing your ability to see in the dark.

You could also put on some fancy night-vision goggles if you wanted to get high-tech about it and had the money.

But your natural, naked eye has its own night-vision capabilities that are actually pretty top-notch — if you know how to enhance and harness them.

How We See in the Dark

Understanding how we see in the dark can better help us understand what we can do to maintain our vision at night. Below we walk you through a thumbnail sketch of how the human eye sees in low-light environments:

Pupil. Think of the pupil as the aperture on a camera. It’s what allows light to enter our eyes. The wider the pupil, the more light can come in; the narrower the pupil, the less light can enter.

Just as the aperture on a camera will open wide in low-light environments to allow more light in, so too will your pupil dilate — open wide — in dark situations.

You may have thought of this widening/narrowing of the pupil as the only mechanism by which your eyes adjust to the dark. But this is just the first step in this process, and not even the most significant one. Human night vision has more to do with the eye’s . . .

Rods and cones. After light passes through the pupil, it goes to the back of our eyeball and hits a thin layer of sensory membrane called the retina. Sticking with the old-school camera analogy, think of the retina as the camera’s film. It’s where our eyes start putting together nerve signals to send to our brains.

The retina is covered with two types of photoreceptors called rods and cones. They’re called rods and cones because those are the shapes they respectively take.

Rods work best in low-level light. They just need a few photons of light to be activated. When we’re looking around in low-light environments, our eyes primarily use rods to see things. The downside of rods is that they don’t see color. That’s why when you’re seeing in the dark, things look more grayscale, and colors don’t pop. Everything is kind of muted.

Cones require a lot more light to be activated. We have three types of cones: red, blue, and green. A combination of these different cones being activated allows us to see in color. Most of our cones are packed in a small part of the retina called the fovea, which is at the very back of the eyeball and allows us to see images in detail.

Photopigments, specifically rhodopsin. Both rods and cones contain light-sensitive chemicals called photopigments. These photopigments convert light energy that hits the retina into electrical activity so that our brains can decipher what we’re seeing. Going back to our camera analogy, think of photopigments as the chemicals that help develop your film.

Rods contain a photopigment called rhodopsin; cones contain a photopigment called photopsin.

Rhodopsin is what allows us to see at night.

But as soon as the rhodopsin is exposed to high-light levels, it decomposes (aka photobleaches), reducing our sensitivity to light in low-light conditions, meaning we can’t see as well in the dark. The brighter the light, the more the rhodopsin gets bleached.

Once your eyes are exposed to less light, the rhodopsin starts to regenerate in your rods. It takes about 30 minutes for rhodopsin to completely restore, bringing you back to optimal night vision. Even though it takes a half hour for rhodopsin to fully regenerate, your eyes’ ability to see in the dark will start to improve as soon as they stop being exposed to the high levels of light that caused their rhodopsin to decompose in the first place. You’ll notice that your low-light vision will slowly get better and better the longer you get used to the lower-light levels.

If you’ve ever experienced going from a bright sunny day outside to back inside your house, and everything looked really dark for several minutes despite the interior lights being on, you now can understand what was happening in your eyeballs — the sunlight had photobleached your rhodopsin, leaving your eyes struggling to see in the suddenly lower-light conditions.

You may have then noticed that your vision gradually got better and better as you sat in the low-light room. That was your rhodopsin regenerating in your rods. Pretty cool, huh?

How to Maintain Your Night Vision

Now that we have a rough idea of how we see in the dark, we’re better equipped to understand how to maintain our vision at night.

The overarching principle is to expose your eyes to as little bright light as possible. Because as soon as the rhodopsin in your rods is exposed to bright light, it bleaches away, taking your night vision along with it. And remember, it takes a half hour to be fully restored!

Looking directly at light bulbs, flashlights, smartphone screens, and even a bright full moon will result in the degeneration of your rhodopsin. So don’t do those things.

How to Maintain Night Vision While Using a Flashlight

Flashlights raise an interesting issue when it comes to maintaining night vision. When working in the dark, you may need to use your flashlight to read directions on paper or look for things in your environment. But the use of this artificial aid will also reduce the rhodopsin in your eyes, reducing your natural ability to see in the dark.

So how can you use a flashlight or headlamp without disrupting your night vision too much?

Consider the idea that you may not need a flashlight after all. When you head out in the dark, you probably have an automatic instinct to reach for a flashlight and feel like wielding one is necessary to see what you’re doing. And it does initially appear that way. But remember, it takes awhile for your eyes to fully adjust to the dark; if you give them that chance, you may find you don’t need a flashlight to see after all. Especially when you’re outdoors and operating under the moonlight.

Only use as much light as you need. These days, most LED flashlights allow you to select how much light you emit from your flashlight. So if you do use a flashlight, select the lowest light setting possible. Remember, the brighter the light, the more your rhodopsin decomposes, so the less light you can use from your flashlight, the better.

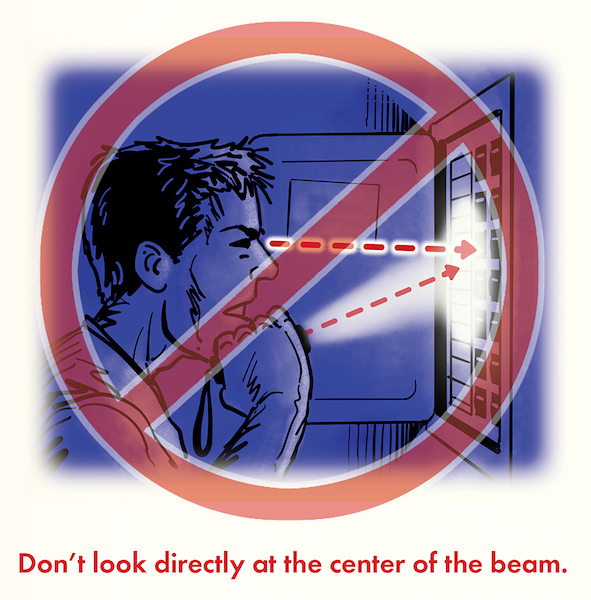

Don’t look at the center of the flashlight beam. When you’re pointing a flashlight at an object in your environment, you have the natural tendency to look at the center of the beam. It makes sense; it’s the brightest part of the light coming from a flashlight. But looking at the brightest part of the light will only accelerate the fading of your rhodopsin, and your night vision along with it.

Instead of looking directly at the center of your light beam, look around its periphery.

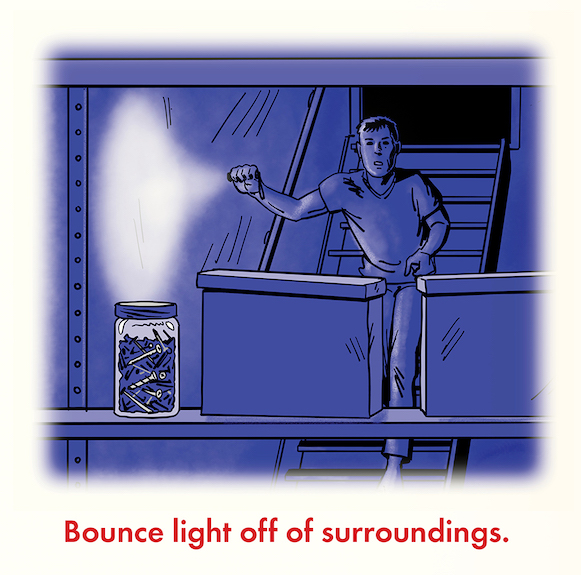

Bounce light off your surroundings. If you’re in a dark room, you can avoid looking directly at your flashlight by bouncing the light off a wall and just using the resulting ambient light.

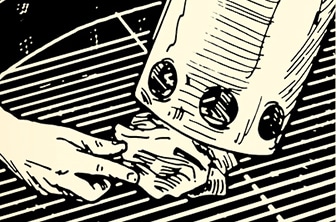

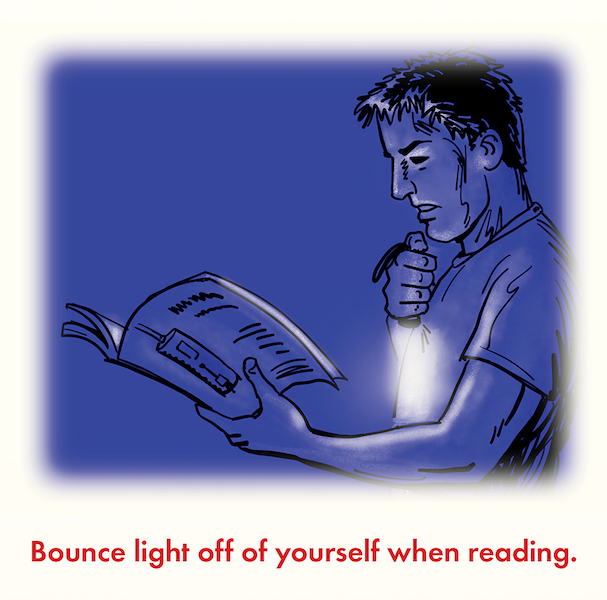

Bounce light off yourself when reading. If you need to read a document with your flashlight, instead of aiming the light directly at the paper and looking directly at the center of the beam, press the bezel of your flashlight flush against your chest and tilt the light. You’re effectively bouncing the light off your chest in order to illuminate the document with much dimmer ambient light.

What About Red or Green Lights?

You may have seen war movies where a unit on a night patrol uses flashlights that emit red light. Here’s why:

Rhodopsin is less sensitive to photobleaching from the long wavelengths of red light. As such, it has a reduced effect on rhodopsin as compared to white light.

While red light has been the color of choice for maintaining night vision, there has been a trend in the military of pivoting towards using green light in low-light situations. Our eyes are more receptive to green light, which means you can see things more clearly with a green light at a lower light intensity. That is, with a green light, you don’t need to have as much light coming from your flashlight to read a map in the dark.

So red light is good for maintaining night vision because it doesn’t reduce rhodopsin as much, and green light is good because you can use less light overall.

Whether you go with one color or the other is up to your preference.

Either way, the same overarching principle outlined above applies: use as little light as necessary. A really bright red or green light beam from your flashlight will still cause your rhodopsin to decompose, taking away your night vision. It all comes back to light intensity. Avoid bright lights, no matter the color.

Other Tips and Tricks to Maintaining and Using Night Vision

Close your eyes before moving from a lighted area to a dark area. If you’re about to leave a well-lit area and enter a dark one, close your eyes for a few seconds before you do so. This will allow your eyes to start generating some rhodopsin in your rods so that when you do open your eyes back up in the dark area, you’ll have a bit of low-light vision at the ready.

Close one eye when moving back and forth between dark and lighted areas. If you’re moving from a dark area to a lighted area and back again, close one of your eyes, so that one of them remains acclimated to each condition. So for example, if you’re going to the bathroom in the night, close your right eye before turning on the bathroom light; after you do your business and turn the light off, open your left eye to navigate back to bed in the dark, as that eye will have maintained its night vision.

This concept also applies to being hit with someone’s high beams while driving at night. Exposure to the bright light of headlights can temporarily blind you. To mitigate that effect, simply close one of your eyes while you drive past the car that’s using its high-beams. This will prevent the rhodopsin in that eye from photobleaching as much, allowing you to adjust back more quickly to low-level light vision.

You may have heard that the reason pirates wore eye patches, was not because they lost an eye in a swashbuckling sword fight, but to employ this very technique: they kept a patch over one of their eyes when above deck, and then switched the patch to the other eye when they went below deck; the now-exposed, still-rhodopsin-filled eye could then amply see in the dark of the interior compartments. While it’s a fun idea, there’s unfortunately no historical evidence to back up this legend.

Use your peripheral vision at night. As mentioned above, our cones are located in a small spot in our retina called the fovea. They give us our sharp, central vision, also called foveal vision. Rods, on the other hand, are found all throughout the back of the retina, which doesn’t make them good for central vision, but does make them good for peripheral vision. You can actually see more with your rods when you don’t look directly at something, so instead of looking directly at objects at night, look side to side of them.