Editor’s note: This is a guest article from Tony Budding.

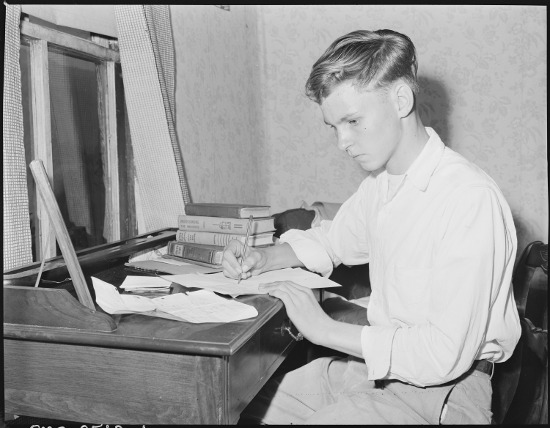

Writing the personal statement for your college applications can be daunting. The questions are usually open-ended with many possible approaches. And, it could end up making the difference between acceptance and rejection.

In this article, I suggest methods for identifying the topic and writing the statement. As a former English teacher, I can tell you that reading numerous mediocre essays in a row is mind-numbing. College admissions officials have a lot of essays to read. The unexpectedly vibrant, authentic, one-of-a-kind personal statement shatters their monotony and immediately distinguishes the application. This can be yours.

First, some logic. Good writing comes from good thinking. In the case of a personal essay, good thinking comes from self-knowledge. Self-knowledge is arguably the greatest asset any man can possess. Therefore, treat the personal statement as a boon.

I believe in progress through extreme effort. You should endeavor to out-work your peers in the acquisition of self-knowledge. There are no shortcuts in this, though there are dead ends. Think of this article as a roadmap of worthy avenues and unproductive alleys.

There are two distinct phases: acquiring self-knowledge and crafting the essay. The former is intrinsically valuable, while the latter is goal oriented. That goal? To have the admissions officer finish reading your essay convinced you belong at their school.

Colleges seek students that support their charter. Ideally, these students understand their passions, challenges, and ambitions, have developed a good work ethic, and are driven by internal motivations (not grades). Such students become lifelong learners. Colleges also aim for diversity of gender, race, geography, academics, athleticism, artistic ability, and background experiences.

That’s the ideal. Your goal is to tap into your values, identify what motivates and inspires you, and demonstrate how this has fueled your pursuit of excellence in some way. The essay is short — typically 650 words or less — so it has to be narrowly focused. You will use this to your advantage by featuring only the parts of you that best convey your ideal inner student.

What Not to Do

First, let’s look at what not to do.

Don’t approach this like a typical academic essay. You are not trying to prove a point, instruct your reader, or explain a thesis. The Authority, the Educator, and the Pontificator are personas you should shun at all costs. You are not an expert in anything; you’re applying to college to learn, and the only thing worse than a pontificating professor is a pontificating student

Don’t have it all figured out. Don’t assume you know exactly what you want to do with your life. And don’t predict the future.

Don’t describe your achievements. Don’t write about something. Don’t summarize. And don’t try to be funny.

Never use absolutes (did you see what I just did there?).

Don’t try to sound like a college student. Don’t try to sound like anybody. Don’t worry if they’ll like you. Don’t lie. And don’t tell the whole truth (it wouldn’t fit anyway).

You Are the Subject

That’s a lot of “don’ts.” What’s left to write about? You.

You are the only you in the world. No one else lives inside your head, thinks exactly like you, feels just what you do, sees the world the same way, or craves the same outcomes.

You are your subject. Not the whole you. Your core values. The motivated you. The inspired you.

This is what colleges are looking for. Every one of the Common Application Essay Prompts asks for some kind of personal meaning, motivation, and/or influence. They want to get to know this you as much as possible.

Self-Inquiry

Writing such an essay begins with self-knowledge, which comes from self-inquiry. Humans are a combination of common and unique elements. Through inquiry, you embark on an inner journey to identify and separate these elements. This profound effort benefits more than just the writing process. Done properly, it forms the bedrock of character upon which you build the foundation of your life.

Self-inquiry is basically asking the question “Who am I?” in as many ways as possible. There are countless ways to approach it. The following questions are examples, oriented toward young men with less experience navigating the inner realms. Start with these questions (or make up your own), but follow each answer with further inquiry. Explore your broad inner landscape with honest reflection.

1. What do you do with your discretionary time and why?

Discretionary activities often reveal inner values. When the homework is done, chores completed, and practices over, what do you do? On a lazy summer day, how do you fill the time? A similar question is, “What would you do if no one would ever find out, and why?”

If you don’t have a lot of discretionary time, switch the inquiry toward your favorite activities. In any case, ask yourself what is it about these activities that appeals to you? Why? Then keep asking why to each answer.

Why is the drill bit that digs the well of understanding. Use it early and often.

Here’s an example. Say you like to shoot hoops in your driveway. Why? Because it’s fun. Why? Well, because it feels good to make a shot. Why? Because it means I’m getting better. Why does that matter? I don’t like losing. Why? I want to win. Why? Cuz if you ain’t first, you’re last! What’s wrong with being last? Losers don’t get good jobs or have good lives.

This process uncovered a link between the fun of driveway basketball and what it takes to have a good life. My experience is that all genuine inquiries reveal some alignment between trivial choices and underlying values. It’s all interconnected, so almost any surface activity can lead to real insight.

At this point, just keep a list of your insights. They will be used later.

2. What injustices in the world are you willing to help fix?

The world is not fair. It never has been and it never will be. Some types of injustice hit your radar stronger than others. Which ones, and why? The question, though, goes one step further. Which ones are you willing to help fix?

This could manifest in a variety of ways. You might volunteer if the issue hits close to home, like child care or soup kitchens. You might research and debate if the issue is political like income disparity or immigration. Or you might decide on a career choice like medical research or international banking if product or service innovations address the need.

The key point is values-based action. It’s one thing to lament corruption in politics. It’s another to do something about it. When your interest and passions are strong enough to motivate action, you know you’re on to something significant.

3. As you think about your life to this point, what events stick out as the most meaningful and why?

What are the strongest memories that you keep coming back to? Which of your past experiences do you reflect on when making decisions in the present? What was it about these experiences that affected you so much? Again ask why?

Sometimes the strongest memories apply to a seemingly insignificant event. Don’t let this deceive you. There is a reason this memory sticks. Use it. Dig in, and keep asking why.

4. How do you define a quality life, and what is required to have it?

While this question can be a stretch for teenagers, it’s worth exploring. Think about your friends and family (both immediate and distant) — who seems the happiest and what do they have in their lives? Include things like careers, family, social activities, vacations, homes, and neighborhoods. Which combinations most appeal to you?

The reason this inquiry is so valuable is that all of life requires compromises. You can’t have it all. For example, an important, high pressure job cuts into relaxation and family time.

Remember the goal of these questions is self-knowledge. You’re not trying to plan out your life, but rather to identify your values. Which aspects pull you? Play the either/or game. A lot of money or a lot of time? A life of travel or a life with kids? Fancy cars or tons of friends? These distinctions are artificial but revealing. And ask “Why?” as often as you can.

5. No man is an island. Who has made the most impact on you and why?

No matter who you are, there are people around you working hard to help you succeed. Parents, relatives, teachers, friends, even strangers. What do they do that supports you? Why do they do it? How does that support affect you both directly and indirectly?

By recognizing their efforts, you can see not just what matters to you, but also how interconnected we are as a species. Since we’re all connected, you also have an impact on those around you. What do you want that impact to be? What do you want others saying about you, what you did for them, and the kind of person you are?

Now push that forward. If that’s the impact you want to have, what skills and experiences do you require to become that person? How well do the colleges you’re applying to fit your needs? It’s possible this inquiry could change where you apply.

Writing the Essay

When you’ve completed these inquiries, you should be able to identify common themes. These are likely the best topics to write about.

Now read the essay prompts carefully. You often have a choice. Any of them can work, so start with the one that seems the easiest (you may decide later that it doesn’t work). Create a rough outline of how you want to answer. Frame your subject in the context of where you are now, oriented toward how your college education will further you along this path. This gives the college insight into both who you are and why you’ll make a good student.

An aside: If you have no compelling answers for these inquiries, I suggest you postpone your college plans until you do. College is a huge investment of time and usually money. If you have no compelling reason to be there, wait. I wish I had. I wasted my college years even though I graduated in four years with good grades because I was not pursuing my own education. It was not until five years after graduating that I began to study for myself. Over the past 20 years, I’ve learned enough for the equivalent of several degrees, but will never regain what my college life could have been.

As you structure your thoughts, identify specific moments of greatest challenge, stress, anxiety, and/or tension. Articulate how these experiences affected you at the time, and how they influence and motivate you now. These are more revealing of your character than great achievements. Plus, your achievements are featured in other parts of your application.

Plan for a long journey. Writing this statement is not easy. There will be a number of false starts. These aren’t failures, but inevitable aspects of refining your thinking. You will also rewrite and edit your essay multiple times.

Nuts and Bolts

Think small. Describe one important event that affected you and influenced your values. Extrapolate this experience into your aspirations for the knowledge and skills needed to pursue your life according to these values.

This works because how you tell stories and describe events reveals a lot about you. An example of this is Joan Didion’s At the Dam. At no point in the 1,000 word essay does she describe herself, yet by the end you have a pretty good sense of what kind of person she is.

Answer the question. Make sure that your essay addresses the prompt. After every rewrite, go back to the question to make sure you haven’t strayed.

Finish with ambitions. You should want something out of your college education. You’ve had past experiences that affect your values. These values motivate you to action in the present. The combination creates an ambition for something in the future (knowledge, experience, skills, participation) for which the college education is necessary.

Use vivid details. Bring the reader into the event with specific information that allows them to experience it in a sensory way. Avoid generic statements: “I was freezing and confused.” Instead, use precise imagery: “The northern wind bit through my sweater, and the shivering distracted me.”

Be bold. Speak unapologetically about your experiences and values. Don’t worry about whether the reader agrees with you or not. They will appreciate the frankness (and if they don’t, it’s not the right school for you).

Be humble. Allow the mysteries of life to remain unsolved. Seek progress, not perfection. The boldness of the above paragraph refers to your values and perspective, while humility is based on the limitations of your knowledge and ability to change the nature of the world. (If Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Mother Teresa couldn’t bring about world peace, chances are you won’t either.)

Keep the end in mind. You’re trying to get accepted into the school. They are looking for intrinsically motivated students who bring genuine curiosity and creative problem-solving to the classroom. Make sure your story highlights these aspects of you.

Have fun. Writing about your deepest passions should be inspiring. Take the inquiry and writing seriously, but don’t take yourself too seriously. Being light and/or playful is different than trying to be funny.

Write well. Care about every word. Cut clutter. Have a clever lead and ending. Rewrite your rewrites. If you haven’t read William Zinsser’s On Writing Well, do it now. It’s a book on writing that’s written so well it’s a pleasure to read. If your essay is due tomorrow, at least read my summary of tips here.

Test for uniqueness. Read your essay as if it were written by someone else. It shouldn’t work. Your statement should be so unique to your life and experiences that it simply doesn’t make sense if anyone else claimed authorship.

Find an editor. Every writer needs an editor. Whether it’s a relative, friend, or teacher, find someone who can help you refine what you wrote so that it says what you mean.

Avoid the don’ts. After every draft, go back and look at the list of what not to do. Some of them have probably creeped in unknowingly. It takes a lot of courage to stay focused, leaving so much else out.

Conclusion

The essay you write for your college applications has a very specific purpose: to get you accepted. To do this, you need to write an authentic, one-of-a-kind essay about your values and ambitions, and how you’ll use your college education to support and achieve them.

Most of your peers are writing boring, bland, and cliche-ridden essays. Admissions officers’ minds are numb from reading hundreds of mediocre essays. Your honest and insightful essay will be a breath of fresh air for them.

To achieve this, you have to outwork your peers on two fronts: self-knowledge and writing. First, invest the time and effort needed to identify what truly motivates you. Then, invest the time and effort needed to write clearly and concisely in your own voice.

Done properly, you will have earned multiple acceptance letters and identified new layers of self-knowledge with which to pursue your life’s ambitions.

Want to share your thoughts on this article? Send us a tweet or join the discussion on Facebook!

______________

Tony Budding taught high school writing and English for several years at Mount Madonna School in California. He also invented a professional sport (Grid), taught logical reasoning in the LSAT prep course for Kaplan, spent a decade way down the rabbit hole of Eastern metaphysical traditions, and recently published an operational definition of consciousness. He is currently Director of Media for DRL, a drone racing startup.

Tags: College