“Fellow-feeling. . .is the most important factor in producing a healthy political and social life. Neither our national nor our local civic life can be what it should be unless it is marked by the fellow-feeling, the mutual kindness, the mutual respect, the sense of common duties and common interests, which arise when men take the trouble to understand one another, and to associate together for a common object. A very large share of the rancor of political and social strife arises either from sheer misunderstanding by one section, or by one class, of another, or else from the fact that the two sections, or two classes, are so cut off from each other that neither appreciates the other’s passions, prejudices, and, indeed, point of view, while they are both entirely ignorant of their community of feeling as regards the essentials of manhood and humanity.” -Theodore Roosevelt

While I have an affinity for the past and believe that nostalgia can be a positive thing, I’m not someone who thinks that everything is worse than it used to be in the “good old days” or that the world is currently going to hell in a handbasket.

Many aspects of our world have gotten better and better, and I wouldn’t wish to be born in any other time in history.

That being said, as in every period of time, while some things get better, some things get worse.

And one thing that is getting worse is indeed cause for concern.

According to studies that have been tracking this since 1979, college students are 40% less empathetic than their counterparts 30 years ago. 40%.

Empathy is not a subject we often associate with manliness; we usually think of it as more of a feminine trait. But even if, as we will soon discuss, men typically do have less empathy than women, it’s a trait absolutely vital to both genders, the glue that holds civilized society together and allows us to experience healthy, satisfying, long-lasting relationships. And if we as men naturally struggle with it to begin with, perhaps it’s even more important that we understand how to hold onto that portion we are capable of cultivating.

What Is Empathy?

Since 1873, when German philosopher Robert Vischer coined the German word Einfühlung (which would later be translated into “empathy” in English) to mean “in-feeling” or “feeling-into,” the definition of empathy has constantly evolved and been argued over.

Empathy is generally conceived as the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes, to understand their feelings and feel them yourself. But of particular debate is whether empathy is the product of a cognitive process-we think about what it would be like to be the other person and then experience similar feelings ourselves, or, more of an involuntary, automatic response.

Recent research has lent much evidence to the latter view. Especially interesting is the discovery of “mirror neurons” in the brains of humans and some other animals. When I am performing a task or feeling an emotion, and you are observing me do so, the same neurons that are being lit up in my brain by actually having the experience, are the ones that light up in your brain just from watching me. That’s why you double-over in pain when you see a fellow man take a hit in the nuts. The empathetic response is automatic and immediate. It’s not a matter of having to imagine what other people are experiencing-they simply effect us.

This doesn’t mean that imagining and thinking about what someone else is experiencing doesn’t lead to greater empathy on our part-it does. But much of empathy is indeed “involuntary” (although we can shut it on and off, the way breathing is automatic but we can hold our breath).

When you feel bad for the victims of a natural disaster and donate money for relief, you’re likely feeling sympathy, not empathy. Sympathy is not an automatic response; we imagine what someone else is feeling and this leads to a desire for action, a desire to alleviate their suffering. With empathy we feel with a person, with sympathy we feel for them. As much as we may have felt sympathy for the victims of the Haitian earthquake, few of us really felt and experienced and understood what a Haitian was feeling and experiencing during that disaster.

Men and Empathy

As mentioned in the introduction, we don’t often associate empathy with manliness. Women are popularly thought to be the more empathetic gender, and studies do at least somewhat bear this belief out.

In the Age of Empathy, biologist Dr. Frans De Waal sums up what we know about the difference between men and women as it concerns empathy:

“Since men are the more territorial gender, and overall more confrontational and violent than women, one would expect them to have the more effective turn-off switch [for their empathy]. They clearly do have empathy, but perhaps apply it more selectively. Cross-cultural studies confirm that women everywhere are considered more emphatic than men, so much so that the claim has been made that the female (but not the male) brain is hardwired for empathy. I doubt the difference is that absolute, but it’s true that at birth girl babies look longer at faces than boy babies, who look longer at suspended mechanical mobiles. Growing up, girls are more prosocial than boys, better readers of emotional expressions, more attuned to voices, more remorseful after having hurt someone, and better at taking another’s perspective. When Carolyn Zahn-Waxler measured reactions to distressed family members, she found girls looking more at the other’s face, providing more physical comfort, and more often expressing concern, such as asking “Are you okay?” Boys are less attentive to the feelings of others, more action-and object-oriented, rougher in their play, and less inclined to social fantasy games. They prefer collective action, such as building something together.”

The differences between males and females seem to manifest themselves before socialization becomes a factor; girl babies are more likely to cry when they hear another baby cry than boy babies are, and two year old girls exhibit more concern for those who are distressed than two year old boys do.

Perhaps most interesting is the fact that in studies on the aforementioned “mirror neurons,” women tended to have stronger motor responses when watching others than men did. One experiment involved men and women playing games with a partner who was really a lab assistant. In one group, the men and women enjoyed working together and playing a game with their partner. Then, while the subjects looked on, their partners were seemingly subjected to pain. The pain areas in both the male and female subjects’ brains lit up as they watched their partners in pain. But in the next group, the partners cheated during the game with the subjects and played unfairly. This time when the subjects watched theirs partner in pain, the pain areas of the women’s brains still lit up in empathy. But in the men’s brains, it wasn’t the pain areas that lit up, it was the pleasure areas. The men got a kick out of seeing the cheater get their comeuppance. The men seemed to be more focused on fairness and justice. Again this is not likely a matter of socialization; the same result has even been found in similar studies with male mice.

These differences are thought to be rooted in the fact that for millenia women have had to be very in tune with the feelings and needs of their offspring. Men, on the other hand, tend to be more aggressive and competitive, and more apt to see others as rivals. They are thus more likely to see empathy as a weakness, as something that gets in the way of climbing to the top and achieving success.

It is also interesting to note that autism and psychopathy, two disorders that affect a highly disproportionate amount of males over females, are both often marked by the inability to experience empathy.

Yet I do not want to overstate the male/female differences with empathy. As with most gender disparities, the differences amount to a bell curve, meaning that there are plenty of men who are more empathetic than the average woman, and plenty of women who are less empathetic than the average man. And as men and women get older, the gaps narrows further.

So what we can say is that women are generally more empathetic than men. But I don’t think this means that men should not be concerned about empathy and developing it. A National League baseball pitcher is there mostly to pitch, but he shouldn’t neglect his hitting all together. It may not be one of our main skills, but we can’t afford to let it go slack either.

Physical Bodies, Technology and the Decline of Empathy

Now that we have provided an overview of empathy, let us return to the study cited in the introduction that college students are 40% less empathetic than they were a couple of decades ago. What could be the cause?

Now there are bound to numerous theories, and I’ll humbly offer mine.

What sticks out to me is that the authors of the study “found the biggest drop in empathy after the year 2000.”

This is also the year that the internet took off and began to greatly alter our lives, diminishing our face-to-face, physical interactions with others and replacing them with conversations conducted as disembodied versions of ourselves. What does this have to do with empathy? A whole heck of a lot.

The amount of communication that takes place between our physical bodies is amazing. We pick up the mood and mirror the body language of others nearby. Studies have shown that couples start to look like each other over time, and the couples that looked most alike after 25 years of marriage were also the happiest (the study controlled for couples that simply looked alike to begin with). A couple of decades of face-to-face communication had physically transformed the couples’ visages.

Empathy derives from the powerful synchrony that exists between our physical bodies. When others laugh, we laugh; when they yawn, we yawn. The smiles and frowns of others cause our mouths to droop or rise in turn. Think of the difference between listening to your favorite band at home and being at a concert where a whole mass of people is connected by the same emotion and moving the same way.

Empathy is communicated between bodies; we do almost literally step into another’s shoes. We map another person’s body onto our own. Our thinking causes our bodies to act, and our bodies cause our brains to think.

Dr. De Waal argues:

“We’re beginning to realize how much human and animal cognition runs via the body. Instead of our brain being like a little computer that orders the body around, the body-brain relation is a two-way street. The body produces internal sensations and communicates with other bodies, out of which we construct social connections and an appreciation of the surrounding reality. Bodies insert themselves into everything we perceive or think….the field of “embodied” cognition is still very much in its infancy but has profound implications for how we look at human relations. We involuntarily enter the bodies of those around us so that their movements and emotions echo within us as if they’re our own. This is what allows us, or other primates, to re-create what we have seen others do. Body-mapping is mostly hidden and unconscious but sometimes it “slips out,” such as when parents make chewing mouth movements while feeding their baby. They can’t help but act the way they feel their baby ought to.”

The Decline of Empathy and the Rise of Anger and Loneliness

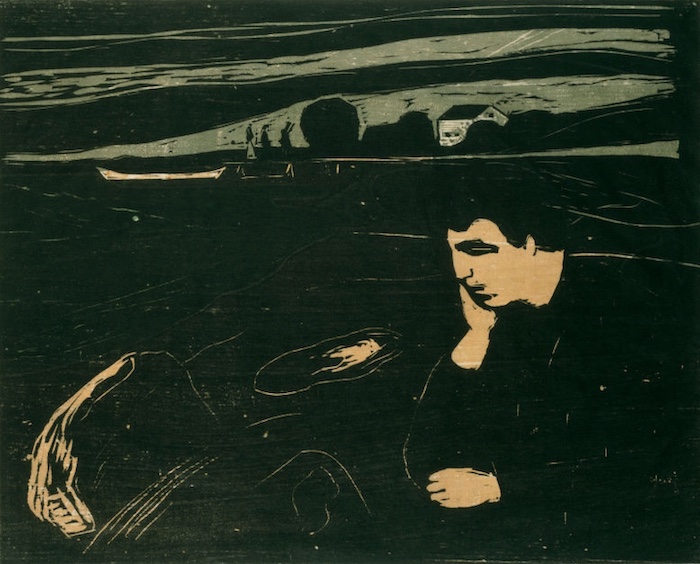

People whose facial muscles become paralyzed often become depressed, lonely and even suicidal. They cannot express themselves fully, but even worse, people tend to avoid them. In a Parkinson’s support group, the mediator noticed that those with facial rigidity were avoided by the other participants. We feed off the transferring of emotions that happens in our face-to-face interactions; these interactions feel empty when we don’t see our emotions reflected back in the other person, and we struggle to empathize with what they’re feeling.

Isn’t so much of how we communicate now done with “paralyzed faces,” with immovable avatars that show no facial expressions, no body language? Is it any wonder that many of us are feeling empty and depressed?

Before I got a “real” job, there was a period where I was working on the website full-time. This seems to be many a man’s dream, and certainly it is nice to “go to work” in your pajamas. But it’s also incredibly lonely. Your day is devoid of human interactions. While I love to interact with AoM’s readers online, I missed empathetic, physical interactions. It was really kind of depressing.

And it’s not just loneliness that our disembodied lives have created, but a culture of acrimony.

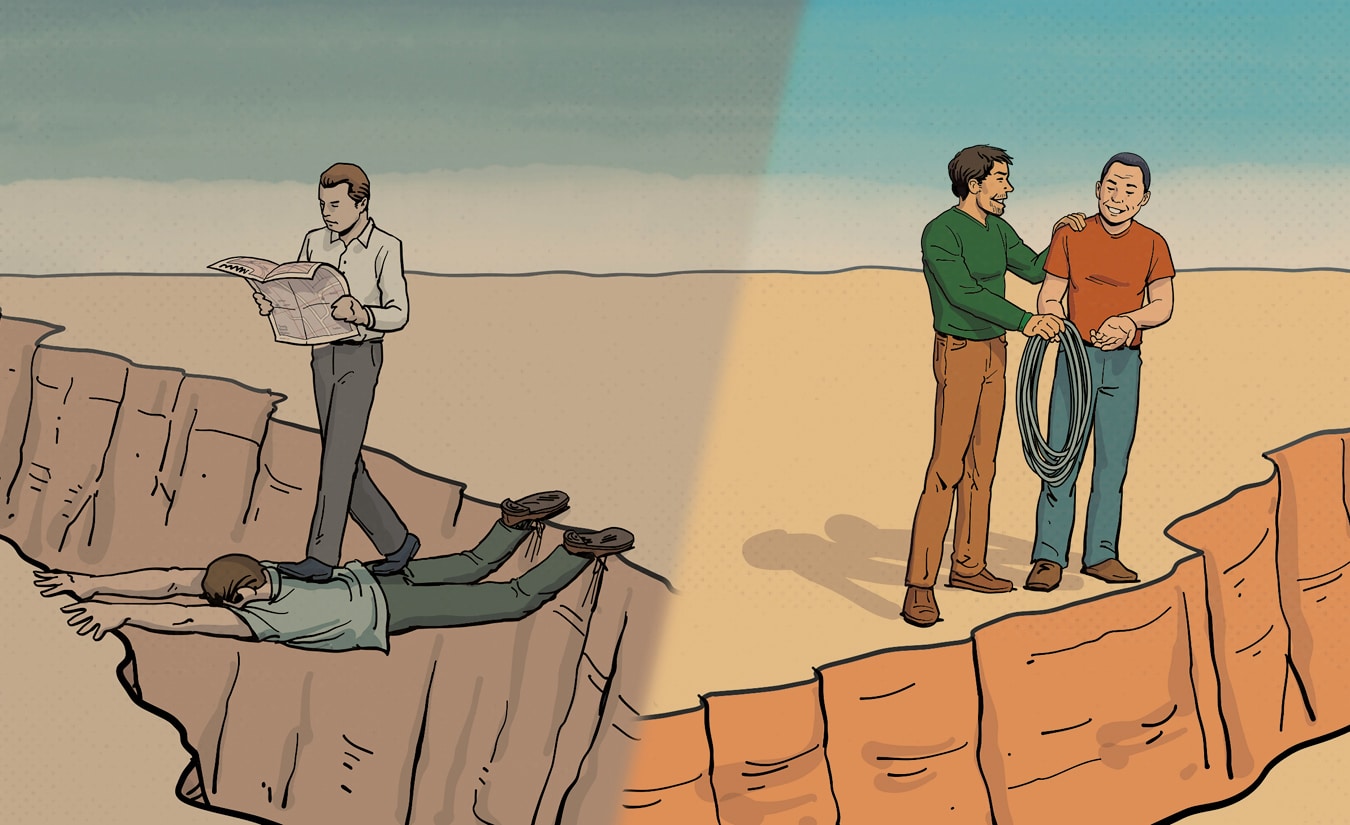

Have you ever been incredibly angry at another person, stewing and brooding about it all day? But then when you finally met up with the person face-to-face and talked to them, the anger just melted away? In the presence of their physical self, those puppy dog eyes, your empathy kicked in. In the absence of these real encounters, minor slights can multiply themselves many times over. One of the reasons long-distance relationships rarely work out.

Yet our internet-saturated lives are now filled with “long-distance relationships.” I read pretty much every comment made on this site, and what often strikes me is how angry some people are. Even if it’s just disagreeing with the inclusion of one movie over another, the commenter seems to be fairly frothing out the mouth. It’s not that I don’t understand; having to spend so much time online has most definitely made me less patient, crankier, and a lot more cynical. The temptation to lash out is ever present. And it comes down to the decline in empathy. Hunched over our computers, communicating as disembodied blobs, we’re suffering a dearth of empathy transference. We’re little islands of one, free from the experience of stepping into another’s shoes, truly feeling what they’re feeling, and understanding where they’re coming from.

Final Thoughts

Whenever I do a post that in any way criticizes modern technology, some inevitably take this to mean I’m a Luddite who wishes he could be cruising along in a horse and buggy. Not so. Come on, you’re reading this on a blog! (See how angry I get?) Clearly I’m a full supporter of taking advantage of modern advances; I love computers and I love the internet. I’m simply an advocate for using technology responsibly and finding balance in our lives.

I’ve been actively trying to find ways to get out and interact with people physically, body-to-body, face-to-face. I want to experience and strengthen my empathy, to understand others, and I know that can’t be done entirely from behind a computer screen. I would encourage others to get out and experience the physical, emphatic side of humanity as well.

Source: The Age of Empathy by Dr. Frans De Waal