As we talked about in a previous post, Kate and I have what might be termed a “Marriage Master Mind.” We share everything just about equally—the blog, parenting, household chores, and so on. We get along really well, especially for people who spend practically 24/7 together and have to balance issues involving both work and romance.

But like all couples, we occasionally have arguments. And a good percentage of them used to be over who was taking care of what, and whether one person wasn’t pulling their weight enough in the relationship.

We’re not alone in this: conflict over the division of domestic duties ranks second only to money problems in creating discord in marriages.

This isn’t just a product of the more egalitarian nature of relationships in our modern age—although that has likely intensified the conflict. Even back in the day when spouses had clearly defined roles–husband worked, wife stayed home—men and women debated who had the heavier burden; was it tougher to go to work or to stay home with the kids?

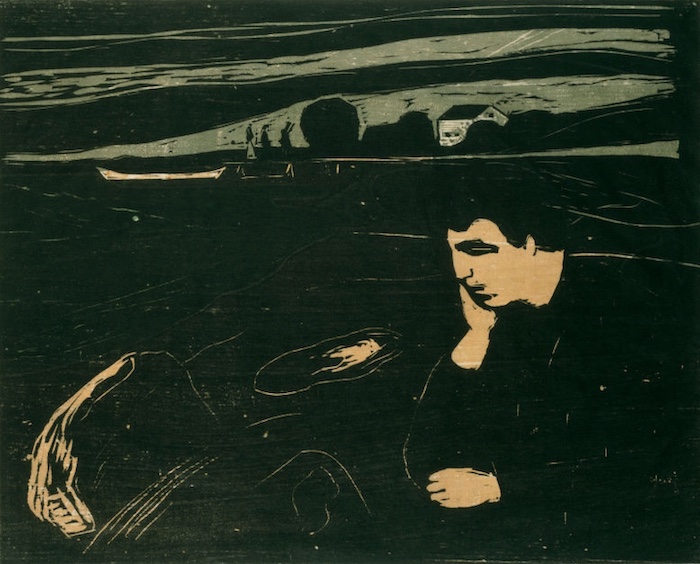

Concentrating on keeping the scales of a relationship exactly balanced can create animosity and discord between partners. This unhealthy state is what we like to call “The Tit for Tat Trap.”

The Faulty Calculations of Those Stuck in The Tit for Tat Trap

Couples who fall into The Tit for Tat Trap base their relationships on strict reciprocity. “I will only do this, if you do that. And if you stop doing what I expect of you, I will stop doing what you expect of me.”

Now relationships based on strict reciprocity can work well for say, two partners joined by a business contract. I give you money, and you give me a service or product. Quid pro quo.

The problem with using a framework of strict reciprocity in a personal relationship is that it is difficult, nay, impossible to exactly calculate the worth of each person’s actions and behavior.

First off, we still haven’t even resolved the debate over which is the tougher lot–working full-time or staying home with children (having had a hand in both, I’d say they’re equally difficult, just in different ways). And does cleaning the bathroom garner more points than mowing the lawn? Is folding the laundry harder than putting it away? Is installing a fan worth more than staying up with a sick child during the night? And that’s not even getting into weighing the emotional stuff. If you’re consistently the rock while the other person is allowed to fall apart, does that tip the scales in your favor? If one spouse is mopey and morose and the other optimistic and cheerful, does the latter get more marks on their side of the relational ledger book?

Compounding the difficulty in measuring the worth of such things is the fact that we are all terrible judges of just how much of the weight we’ve been pulling. This is because all human minds are subject to what is called the “availability heuristic.” Heuristics are problem-solving mental shortcuts our minds use to figure things out…but they’re not always all that accurate and are prone to biases.

In the case of the availability heuristic, we tend to believe that the easier it is to pull something from our memory (the more available it is to us), the larger the category and the more frequently the thing happens. So for example, since the media gives so much coverage to things like gruesome and unexpected deaths, people think that you’re more likely to die in a plane crash than a car wreck, and more likely to die in an accident than from a stroke, even though in both cases that’s simply untrue, and untrue by a wide margin of error. But since such vivid deaths are at the forefront of our minds, and are easy to retrieve from our memory, we believe they happen with greater frequency than they actually do.

One of the things that influences the availability heuristic is whether or not something happens to us personally, or to another person. Things that we experience ourselves are obviously more salient, and thus reside closer to the forefront of our minds—and this makes them easier to retrieve, which sways us into believing they happen with greater frequency than they do.

Which brings up back to relationships. Because it’s much easier to recall all the efforts we’ve been making from day to day, and it’s harder to remember what our partner’s been up to, we’re prone to think that we’ve been doing much more than the other person has. It’s easy to remember how we’ve been staying up late doing the taxes and spent all Saturday cleaning out the garage, but harder to recall that the wife spent Saturday doing errands, and was planning your kid’s birthday party while you were gathering together the year’s receipts.

In a study done by Ross and Sicoly, couples were asked to estimate what percentage they contributed to taking care of specific household chores. If the husbands and wives had been accurate in their assessments (say the husband said he took out the trash 60% of the time, while the wife said she did it 40% of the time), when they added up their respective percentages, each total should have come out to around 100%. But that’s not what happened; the totals consistently exceeded 100%. In other words, each partner overestimated their respective contributions to each chore. And the same result was found for other social contexts as well (such as group projects for school or work).

All of which is to say: when it comes to accurately keeping score in a relationship, we suck.

“Nice Guys” Are Scorekeepers

At this point you might be thinking to yourself, “Scorekeeping is something douche-y guys do in a relationship. But not me. In my relationships I’m an incredibly generous and giving guy.”

Unfortunately, if that’s what you’re thinking, there’s a good chance that you might be one of the worst offenders of all.

In the book No More Mr. Nice Guy, Dr. Robert Glover describes the problems of a set of men who are not simply “nice,” but who suffer from “Nice Guy Syndrome.” These guys never assert their own needs and let people walk all over them, all in the hope that shaping themselves into what others desire will win them love and approval. And yet such behavior inevitably leads instead to unhappiness, frustration, and barely suppressed rage.

Even though they suppress their needs, Nice Guys still want those needs met somehow, which naturally creates a real dilemma. Glover articulates the problem this way: “How can they keep the fact that they have needs hidden, but still create situations in which they have hope of getting their needs met?” Nice Guys accomplish “this seemingly impossible goal” by resorting to methods that are “controlling, manipulative, and unclear” and involve the use of what Glover calls “covert contracts.” These “unconscious, unspoken agreements,” Glover explains,

“are the primary way Nice Guys interact with the world around them. Almost everything a Nice Guy does represents some manifestation of a covert contract.

The Nice Guy’s covert contract is simply this:

I will do this ___________(fill in the blank) for you, so that you will do this_____(fill in the blank) for me. We will both act as if we have no awareness of this contract.”

Nice Guys give a ton of themselves to their partners, to be sure, but they give to get. Strings are strongly attached, and under the guise of doting generosity, they actually demand total reciprocity. They give as a way to indirectly get their needs met and in the hopes of getting something in return. And if their partners fail to pick up on this veiled message, and reciprocate in a way the Nice Guy deems equivalent, he grows angry and bitter towards them.

Avoiding The Tit for Tat Trap

So you how do you avoid falling into The Tit for Tat Trap? Here are some ways to steer away from it:

Squash the availability bias. The good news in all this, is that of the many cognitive biases that distort our thinking and decision-making, psychologists say that overcoming the availability heuristic is one of the most easily achievable.

In the study done by Ross and Sicoly mentioned above, researchers found that simply making the spouses aware of the bias worked to undermine it, so that they were able to more clearly see what their partners had been contributing, and not just their own contributions. After reading this post, hopefully the next time you’re prone to feeling that you’ve been pulling more weight than your partner, you’ll stop to put yourself in their shoes, and realize they’re probably thinking the exact same thing.

Quit mind reading. If you’re feeling under-appreciated and that you’ve been pulling more weight than your wife, don’t stew about it in silence. Say to her, “I’ve been feeling crazy busy lately. Is there anything you could help take off my plate?” She’ll either 1) Be happy to help and happy that you let her know how she could help you. 2) Let you know that she’s got an equally full plate, and all the things she’s been up to. At which point, if you calmly reflect on it, you’ll realize that the availability bias had steered you wrong. Or, 3) She won’t offer to help you even though she has the time to do it. See note about unhealthy relationships below.

Just by doing the two points above, Kate and I have virtually eliminated this source of conflict from our relationship. If you need further help, read on.

Take responsibility for your own needs. As we mentioned above, Nice Guys expect their partners to meet all their emotional needs, but can’t make those needs known, and so resort to “covert contracts,” in hopes their partners will take the indirect hint and reciprocate their “generosity.”

Dr. Glover recommends that recovering Nice Guys squash this unhealthy behavior by taking responsibility for their own needs. He exhorts the reader to remember that besides your parents, “No one was put into this world to meet your needs but you.”

I agree with this for the most part, but I do think all humans have needs for love and sex that cannot be met entirely on one’s own (trying to do so is like giving yourself a massage—not very satisfying). But the point is a good one: you can’t rely on someone else to make you a happy, healthy, confident, sane man; you take responsibility for becoming whole yourself, and you bring that whole self into a relationship with another whole self. When you don’t rely on someone else to meet your needs, you are then able to give to and do things for your partner…with no strings attached. Just because you genuinely want to.

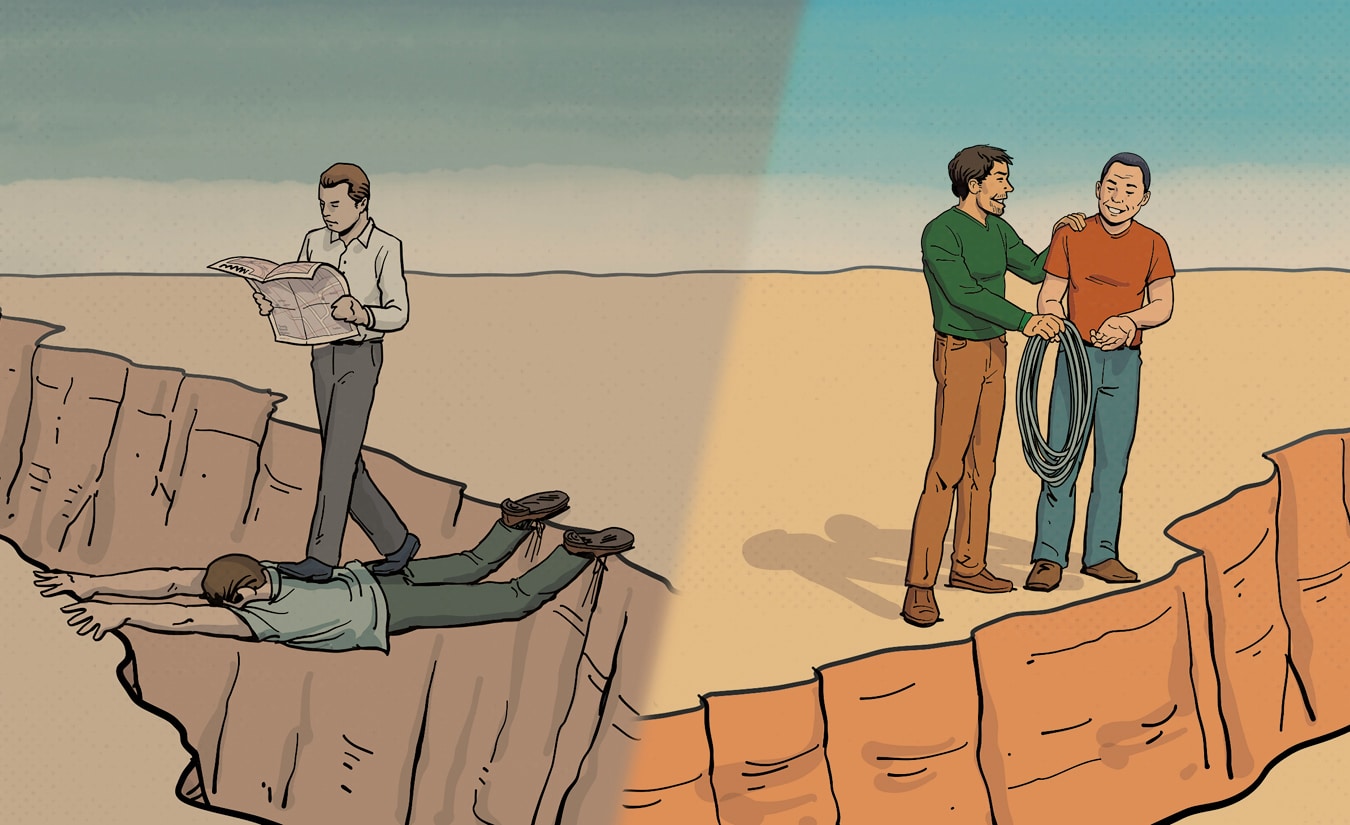

Let it flow. At this point, I am sure some of you are thinking, “But, what if you give a lot to your partner, but she doesn’t reciprocate at all? Isn’t that a recipe for getting walked over and taken advantage of?

Certainly, setting some boundaries is important. Psychologists tell us that if you reinforce a person’s bad behavior with a reward, then they’ll keep repeating that bad behavior. So it’s definitely a bad idea to bring your wife flowers right after she spent a half hour berating you.

But in general, when you’re in a healthy relationship, things just flow naturally, without the need for scorekeeping or fears of being taken advantage of. You give because you love the person, and they do the same. Sometimes you’re doing less because you’re sick in bed with the flu or feeling down in the dumps, and sometimes they’re having a rough patch and you’ve got it together. Things may feel uneven in the short-term but they’ll inevitably ebb and flow in the long-term; the scale tips from one side to the other over and over. You just got to ride the waves. If you are both committed to the relationship and to loving and serving each other, it simply flows.

But what if I’m in an unhealthy relationship? My wife is so angry/stingy/crazy!

Well first off, as the saying goes, when you point your finger at someone, two fingers point back to you. Or as Glover puts it:

“Wounded people are attracted to wounded people. When Nice Guys enter a relationship, they frequently choose partners who look more dysfunctional than they do. This creates a dangerous illusion that one of them is sicker than the other. This is a distortion, because healthy people are not attracted to unhealthy people—and vice versa. I frequently tell couples that if you have one obviously wounded person in a relationship, you always have two. No exception.”

All of which is to say, the first thing you need to do is figure out what stuff about yourself you need to work on. Sometimes (certainly not always) changing yourself can cause the other person to change and the relationship dynamic to heal. Treating someone in a healthy manner can thaw the ice between you and soften their heart, which will change their behavior.

Oftentimes for couples stuck in The Tit for Tat Trap, a stalemate has been reached where neither partner wants to make the first move and do something for the other person. They feel that to do so would show weakness. And showing weakness in a relationship has become something of an all-consuming fear amongst men these days, since lots of “seduction” gurus make it sound like if you don’t always have the upper hand, you’ll be instantly transformed in a woman’s eyes from attractive hunk to simpering wiener.

So if you find that pride is getting in the way of making the first move, try looking at it not as some big, permanent change you’re making in your behavior or mindset, but simply as an experiment. You’re not capitulating—you’re just conducting an experiment, with a predetermined start and end date. You’re a scientist who’s simply going to test a hypothesis. Then for say one week, take the initiative in doing things for your partner—like leaving her a love note each morning.

At the end of the week, assess the result. Sometimes something like this is enough to shift the relationship dynamic to get you both back in a healthy groove.

But not always of course. If she’s the wrong kind of woman, it could very well increase her disdain for you, or not change her feelings about the relationship at all. If this is the result of your experiment, then if you’re dating, you should probably find another girl. And if you’re married, you might consider getting some couples therapy.