Winston Churchill once said of his only son: “I love Randolph, but I don’t like him.” It’s a sentiment many a parent with a tumultuous relationship with one of their children can relate to, and well describes both how Winston felt about Randolph, and how Randolph felt about his father.

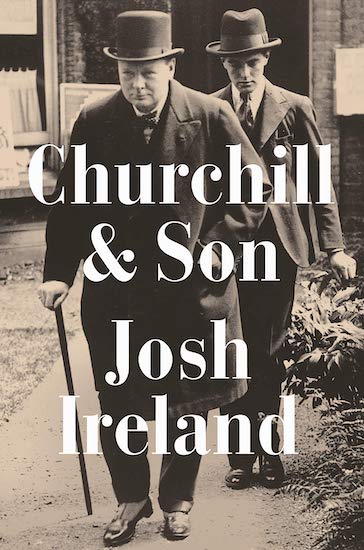

My guest today details Winston and Randolph’s incredibly close and yet terribly complex and combustible relationship in his book, Churchill & Son. His name is Josh Ireland, and we begin our discussion with how Winston’s own harsh and neglectful father influenced his decision to be a much more involved and ultimately indulgent family man, and the way he spoiled a son who was already inclined towards appalling behavior. Josh describes the manner in which Winston and Randolph both bonded and fought, and the effect the trouble Randolph caused had on the relationship between Winston and his wife. We then get into how World War II, and the way Winston may have encouraged Randolph’s wife to cheat on him with an American diplomat, affected Randolph’s relationship with his father for the worse. Josh explains the outsized expectations Winston had for Randolph, the points at which father and son respectively realized they’d never be fulfilled, and the lesson to be taken from their story about the cost of parents imposing their own dreams on their children. We end our conversation by discussing why it is that the children of great leaders rarely turn out well themselves, for, as Randolph himself observed, “Nothing grows in the shadow of a great oak tree.”

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- Why was Josh interested in tackling the relationship between Winston and Randolph

- What was Churchill’s relationship with his father like?

- Why did Churchill still revere his father in spit of the terrible treatment?

- How that terrible childhood impacted the future leader’s abilities and ambition

- Where is Churchill at in life when he marries and has children?

- What was Winston like a father?

- Why was the relationship between Winston and Randolph so fraught?

- What about Clementine, Randolph’s mother? What was their relationship like?

- How WWII impacted Churchill’s relations with his kids

- Why did the PM decide he needed Randolph by his side?

- Randolph’s first wife, Pamela, and how Winston took advantage of them

- What happened after the war?

- What did Josh learn about fatherhood from studying this relationship?

Resources/Articles/People Mentioned in Podcast

- Rogue Heroes by Ben Macintyre

- How Churchill (and London) Survived the Blitz of 1940

- The Audacious Life of Winston Churchill

- The Making of Winston Churchill

- The Winston Churchill School of Adulthood

- Chartwell

- Stalin’s Daughter

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. Winston Churchill once said of his only son, “I love Randolph, but I don’t like him.” It’s a sentiment many a parent with tumultuous relationship with one of their children can relate to and well describes both how Winston felt about Randolph and how Randolph felt about his father. My guest today details Winston and Randolph’s incredibly close and yet terribly complex and combustible relationship in his new book, Churchill & Son. His name is Josh Ireland and we begin our discussion with how Winston’s own harsh and neglectful father influenced his own decision to be a much more involved and ultimately, indulging family man and the way he spoiled his son who was already inclined towards appalling behavior. Josh describes the manner in which Winston and Randolph both bonded and fought, and the effect the trouble Randolph caused had on the relation between Winston and his wife.

We then get into how World War II and the way Winston may have encouraged Randolph’s wife to cheat on him with an American diplomat affected Randolph’s relationship with his father for the worst. Josh explains the outsized expectation Winston had for Randolph and the points at which father and son respectively realized they’d never be fulfilled and the lesson to be taken from the story about the cost of parents imposing their own dreams on their children. We end our conversation by discussing why it is that the children of great leaders rarely turn out well themselves for, as Randolph himself observed, “Nothing grows in the shadow of a great oak tree.” After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/churchillandson.

[music]

Brett McKay: Alright, Josh Ireland, welcome to the show.

Josh Ireland: Thanks, and well, really pleased to be on.

Brett McKay: So you got a new biography out about Winston Churchill, but this isn’t just any other regular Winston Churchill biography, where you look at the entirety of his life. You focus in on his relationship with his firstborn son, Randolph Churchill. Curious, what kick-started your project in looking at and writing a biography of this father-son relationship?

Josh Ireland: It’s quite weird. I can pinpoint exactly where I was and when. I was on holiday and I was reading Ben Macintyre’s really good book about the early days of Britain’s SAS, and right in the middle of that narrative, suddenly, Randolph, who’s Winston son, makes this extraordinary cameo right in the middle of the desert with these tough soldiers. Suddenly, this fat, drunk, angry, clever, brute and damaged man strides in and he steals the show for a few pages and then disappears off. And that got me thinking. I realized that I knew nothing about this man. I’m barely aware that Winston had a son. And then the more I read about Randolph, the more I realized that it was really strange that for all the many biographies of Winston, Randolph barely appears, when actually, if you look at how Winston felt about him, Randolph was the absolute center of his life. And that made me realized that it was a different way of looking at Winston, a different way of understanding him as maybe as a more human, more emotional, more vulnerable figure. And the other thing I was really interested in was, what it’s like to grow up with a man who is regarded as the greatest person in history, what effect that has on you, how you ever kind of build a life in that really long and punishing shadow.

Brett McKay: Well, I hope we can see in this conversation, it was… Their relationship was fraught. That’s an understatement, I think.

Josh Ireland: [chuckle] Yeah.

Brett McKay: But I think to understand Churchill’s relationship with his son, Randolph, you really have to understand Churchill’s relationship with his own father, who’s also named Randolph, Lord Randolph. Can you tell us about Lord Randolph, what was he like? And then we can talk about his relationship with his son, Winston Churchill.

Josh Ireland: Well, Lord Randolph’s one of the most interesting and controversial, and strange figures in the 19th century. He was son of a duke and he basically revolutionized the Conservative Party, dragging them into the Modern Age. And just as he was about to take power himself, he takes this extraordinary gamble which backfires and just throws him out of power. Outside of his political life, he led an extravagant existence. He spent wildly. He and his wife, Jennie, were plunged into profound debt and even alongside that, he was suffering from this progressive brain disease, which people at the time felt was probably syphilis, but now seems to be something unidentified but which has a lot of the same symptoms. So his brain was rotting, his body was rotting, even as he was stepping away from the political limelight. But all of this busyness and all this danger and all of this excitement left no space at all for his two children, and that meant that Winston was this very sensitive, shy child, who was desperate for attention from a father who barely seemed to notice him.

And so there’s all these terrible scenes where Lord Randolph goes to address a political meeting in Brighton, where his son was at school and he didn’t even bother to cross the road to say hello to his son. He barely knew what country his son was in, he couldn’t tell you how old his son was. And whenever Winston tried to form any kind of bond with him, he’d have this horrible rebuke where his father basically told him that he was worthless, would never gonna amount to anything, and that he was almost ashamed to have him as a son, which had a massive and a long-lasting effect on… Psychological impact on Winston.

Brett McKay: And some of the letters are just brutal, where he’s writing to his father and his father just dresses him down, and Randolph was like, “You’re pathetic. You’re never going to amount to much.”

Josh Ireland: [laughter] It’s… I just can’t imagine any father talking to their child like that. To do it once is pretty bad, but he did it repeatedly. Even the last letter, he writes to him just before he dies, he’s just saying, “You’re never gonna amount to anything. You’re a failure, you’re pathetic, you’re stupid, you’re worthless.” He said, “You’re gonna become a degenerate. You’re gonna degenerate into a shabby, unhappy, and futile existence.” And Winston got that letter and he never saw his father again. They were almost the last words he ever heard from his father.

Brett McKay: And what’s so shocking about this, despite being treated so poorly by his father, Churchill, he still deeply admired and loved his father. What was going on there? Can you… Can you figure…. Did you figure out why Churchill had this romantic ideal of his father, even though his father… And the reality his father was nowhere near that ideal?

Josh Ireland: I think it was psychologically essential for him. I think he retreated into a fantasy, where he believed that his father would have grown to love and admire and respect him. And everything he did, really, right through the course of his life, was part of this dialogue with his father, trying to persuade his father’s ghost that he was worthy of the affection that he hadn’t been given 30, 40, 60 years beforehand. There’s this extraordinary short story that Winston writes in the last years of his life where he imagines his father returning to him, and it’s just that… He said could never stop talking to his father or thinking about his father. And I think he just needed to believe that his father would ultimately have grown to love and respect him. And so he had that fantasy and lived it out throughout the entire existence.

Brett McKay: And do you think Churchill’s, his terrible relationship with his dad, do you think that helped him become the Winston Churchill that led England during World War II?

Josh Ireland: Yeah, undoubtedly. I think that damage that was wrought on him, eventually that drove his ambition and it drove his sense of purpose, and it made him go further and harder than I think he would have otherwise. That’s what instilled in him, that ferocious work ethic, that burning desire to prove himself. So it’s grim irony that Britain’s survival in 1940 was all dependent on the bullying, cruel behavior of a man, 60 years beforehand.

Brett McKay: And I think, wasn’t it Randolph that wrote… Or it might’ve been Winston, something like “most great men”… He even thought about this. “Most great men they had a really bad childhood.”

Josh Ireland: Yeah, and that’s Winston entire line, yeah. He really thought it was essential as part of this growth of a great man, to be subjected to that kind of brutality as a young person, which is what makes his own attempts to mold his own son seem almost perverse in that he took exactly the different… Exactly the opposite approach.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about his son. So Churchill had a terrible relationship with his father. He gets married and at what point in his life did he become a father? Where was he at in his political career?

Josh Ireland: He was in his mid-30s when he finally marries. He meets a woman called Clementine Hosier, who comes from a similarly damaged emotional background and they quite quickly have kids. They have a daughter, Diana, a year after they get married and then Randolph follows a couple of years later. And their marriage coincides with the moment that Winston’s political career really begins to take off. He becomes the youngest member of Cabinet for 50 years. Initially, he’s President of the Board of Trade, which isn’t a particularly significant role, but it’s still important. Then he becomes Home Secretary and then after that, becomes Lord of the Admiralty, which makes him one of the three most powerful men in the entire British Empire at the time. So he’s really flying by the time he actually becomes a father.

Brett McKay: Alright, and so he named his son after his father, Randolph. And as you said, Churchill had this really terrible relationship with his own father. He decided from the get-go that he would do things entirely different with his kids, particularly with Randolph. Where there was scorn, Churchill would heap praise. So how did that… What did that look like? How did Churchill give Randolph the praise and approbation that he craved himself as a child from his own father?

Josh Ireland: Yeah, Winston was very self-consciously, a very, very different parent to how his own father had been. For one thing, he was just much more present. I’m not sure Lord Randolph ever went into his children’s nursery. He certainly never gave any of his kids a bath. And when Winston was around… And it should be said, Winston had this incredibly busy, extravagant social life and his work dominated his existence, but when he could be there for his children, he was this intense, vigorous, charismatic presence. He loved all of his children and he was unashamedly affectionate, but it was Randolph that he adored more than any of the others. And I think from an early age, all of Randolph’s sisters knew that their brother was the favorite, and Winston showed that in lots of ways. He fed Randolph oysters from the table. When Randolph grew older, he would be encouraged to come and sit with prime ministers and great other political figures, and Winston would wave his cigars at David Lloyd George or Herbert Asquith and tell him to shut up and let his son speak.

And from a very early age, Winston encouraged Randolph to believe that he would become a great man, that he would probably become a prime minister or some other great figure. He praised him. He told him how clever he was, how beautiful he was, how funny he was. And whenever anyone else tried to discipline Randolph, Winston would step in and protect him. There were never any consequences, no matter what Randolph did, and Randolph was an appallingly mischievous child. Winston defended him and would just say that it was high spirits or a sign of his cleverness.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s talk about him being an appalling child. So he was a terror from the get-go. And we talked about some of the stuff that he did as a kid that were just crazy, but Churchill’s like, “Yeah, that’s… He’s just a clever boy.”

[laughter]

Josh Ireland: Yeah, the same [0:11:53.5] ____ etch. He was just… He must have just been… He was uncontrollable, really. He used to phone up the government departments, pretending to be his own father. He’d impersonate his voice. There was one day when David Lloyd George who was, at the time, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, came to visit the church, it was at a country house, and Randolph urinated on him from an upstairs window. It’s just extraordinary.

There was… No nurse maid stayed employed by the Churchills more than a couple of months, ’cause usually they’d be broken by this demonic child. And he was charming and he was funny, but he was… There was no one… Nobody could stop him from doing whatever he wanted.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the story with the nannies… He’d run them off, they would pack their bags. They would be chanting at the stairs, “Nanny’s leaving! Nanny’s leaving!” And you’re like, “What in the… “

Josh Ireland: I know, and it’s just, it’s funny on one level and then also just horrifying to think what all these poor teenage girls must have gone through. This big country house, suddenly this blonde, angelic demon starts yelling at them, and there’s no one that would protect them from him.

Brett McKay: Yeah, like you said, during this time, Churchill really didn’t do anything about it.

Josh Ireland: No. I mean, if anything, he encouraged it. I think he saw it as a sign of his son’s vitality. A big part of Winston’s own myth was that as a child, he’d been the naughtiest boy at Harrow, that he’d been stupid at school, that no one had thought he would make anything of himself, that he was forever getting into fights, that he was forever getting into arguments. And the same was true of Randolph. So, when Randolph fought with people at school, or when Randolph’s teachers tried to remonstrate with either Randolph or Winston, Winston would just laugh. And I think Randolph was self-consciously imitating his father. He knew that legend about Winston as the naughty child. I think he saw it as an important part of being a Churchill, as a way of demonstrating that as a Churchill, you didn’t follow other people’s rules.

Brett McKay: And do you think… Yeah, Randolph was a terror from the get-go. Do you think there was an inborn temperament that contributed to that? Or was it… Do you think it was primarily driven by Churchill’s overindulgence?

Josh Ireland: It’s difficult… I think there’s something innate there. There’s lots of talk about streak of Churchill madness that goes from Lord Randolph to Winston to Randolph. There are generations of Churchills that have suffered from this malady. I think there’s probably some truth to that, and I think, clearly whatever was there, planted there by nature, was encouraged by Winston’s own behavior. He created a perfect environment for that, that bad behavior to grow.

Brett McKay: Alright. So when Randolph was a boy, he was peeing on prominent politicians, [chuckle] but then as he’s gotten to a young man, the problems just got bigger. What was he like, high school, and then in early on, in his own launching off into adulthood? What problems did Randolph create for Churchill?

Josh Ireland: I think he… I think the thing about Randolph is that all of Winston’s faults are present in him. But they appear in a grander, more extravagant form. So, Winston was barely out of debt right through his life but could just about keep on top of it. Whereas Randolph ran up unbelievable amounts of debts by spending money he just didn’t have. He’d buy diamonds for girlfriends or friends. He’d turn up, when he was still a student, he’d turn up at Winston’s house in a chauffeur-driven Bentley. He bought flowers, he bought drink. When he stayed in a hotel, he’d stay in the master suite. And all of this went alongside like a ferocious appetite for drink and sex, and eating.

There are extraordinary descriptions of him, his eyes growing as he saw a pork chop being brought to the table. And he argued with everyone. He never stopped talking when he was at Eton, the high school. There were other people that actually threw him out of a window to see if he would stop talking. And they lobbed him out of the first floor of the window, saw him crash to the ground and he just carried on talking. But mostly, it was arguments. He was arrogant, he was clever, and he thought he knew better than anyone else, and was never afraid of speaking up, which is a really admirable quality sometimes, but clearly could get him into a lot of trouble.

Brett McKay: And this is also when you start seeing what people described as rows, bloody rows between Winston and Randolph. What kind of arguments would they get in, were… Basically it would be like yelling matches essentially?

Josh Ireland: Yeah, the two men loved each other. They really deeply loved each other. And I think that love meant… All that affection, all that emotion, meant that most of the time, they were like a adoring couple. They’d tell each other how wonderful they were. They’d spend weekends in each other’s company. They’d go on holiday together, they’d go drinking together. They’d eat in restaurants together, they’d plot together, they’d go hunting together. But that close proximity also meant that when things went wrong, that it was so charged that they went really, really wrong. Randolph couldn’t control himself when he lost his temper. He’d throw chairs, he’d storm, and Winston had exactly the same faults. And often, the arguments they had were over tiny things. They were perceived slights. They were like tumultuous, romantic relationship.

They could be jealous of each other, they could be jealous of… They could be disapproving of each other’s behavior, and then Winston was brilliant at bringing them back together. He valued his son’s friendship and his son’s love, and couldn’t bear the idea that anything could stand in the way. So, after a huge argument, Winston would invariably be found going to Cartier’s to buy a new bracelet or watch for his son to try and make up. But there were times when their arguments were so fierce, that Clementine, Winston’s wife and Randolph’s mother, refused to be in the same room as them. It must have been terrifying to see. They’re both big men, they both drank a lot, they both had loud voices, they were both very sure of themselves and they didn’t care what anyone else thought about them.

Brett McKay: Speaking of Clementine, this was another… This added to the tension between… With Churchill and Randolph because Clementine was extremely protective of Winston Churchill. She even said that like, “My whole life now”, once they got married, “Is devoted to Churchill, Winston and his career.” And Randolph got in the way of that. And Clementine, she kinda… She didn’t really like her son… Not the nicest way… She didn’t like Randolph at all. What was that relationship like between Randolph and Clementine?

Josh Ireland: Yeah, I think Randolph resented his mom… Mother for pouring everything she had into his father and there was very little left over for the other children. And I don’t think he ever forgave her for that. And as far as Clementine was concerned, I think she saw Randolph as the incarnation of all the worst parts for her husband. She admired Winston immensely, but she also knew that he was susceptible to extravagance and gambling and drinking, and that she thought Randolph was a bad influence when his father would just have a strange way of looking at the world. And I think also she was deeply jealous of him because Winston, especially in Randolph’s early years, clearly privileged him over anybody else including her. She thought that she was at the center of his life and then as Randolph enters his twenties, she realizes that she’s been pushed to its edges and I think she found that very hard, and so they were in… In a sense, they were in constant competition for Winston’s affection and love and attention and that meant that their relationship was incredibly uneasy, suspicious and very, very fraught.

Brett McKay: Did it affect Clementine’s and Winston’s marriage? Was there tension there because of Randolph?

Josh Ireland: Yeah, I mean, I think for a long time because Winston was so uninterested in what was going on in anyone else’s head or heart apart from his own, I think he didn’t notice but as time went on, I think it became maybe the only significant argument that he and Clementine ever had, that they… This was the one thing in their marriage that threatened to push them apart because then they had this long successful bond for upwards of 50 years, but Randolph was the only thing that ever came between them because Clementine felt that Randolph could potentially be the end of Winston, that Randolph could be the reason that Winston wouldn’t go on to achieve all of his dreams and she did everything she could to try and to protect Winston from his son, was Winston was obsessed with Randolph. He wanted to spend as much time as he could with him, he wanted to do everything he could to help Randolph, and so those two views would… They couldn’t really would be reconciled.

Brett McKay: So, what’s interesting too, you note in the book when Churchill was in his wilderness years, when he was basically out of power, a pariah, this was before World War II, this was when his relationship with Randolph got really, really close. Randolph became a confidant, they spent a lot of time together ’cause Churchill didn’t have much going on but then World War II starts, Churchill is made Prime Minister. How does their.. The relationship between him and Randolph change with the start of World War II?

Josh Ireland: So I think it changes almost overnight after Winston becomes Prime Minister, that they have been accustomed to phoning each other all the time and writing letters and spending huge amounts of time in each other’s company, and in a sense although Winston had been a Cabinet Minister, there was a… You could see that in the wilderness years that maybe his career was coming to an end and it must have felt to Randolph as if the future was his, and then suddenly Winston becomes Prime Minister, he’s surrounded by the whole apparatus of government. He doesn’t have time to think about his son because Britain’s in the greatest power that it has been maybe for almost 1000 years and so Randolph finds himself very abruptly pushed to the margins of his father’s life and he finds it very, very difficult to adjust to that new status because he used to be able to just walk into his father’s room and to start talking and now there were secretaries in his way or generals or chiefs of staff, and I don’t think he ever… Their relationship really ever recovered from that.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the way you describe it, I can see it’s been really hard for Randolph. There was instances where he wanted to see his father but Churchill’s private secretaries wouldn’t let him and wrote these patronizing letters like…

Josh Ireland: Yeah, exactly.

Brett McKay: “Be a good boy and leave your father alone.”

Josh Ireland: Exactly, which is… It must have been devastating to Randolph because one of the other things that when Winston becomes Prime Minister, he very quickly assembles a new government and he gives appointments to a lot of the people that had stayed loyal to him right through the wilderness years, but also to the people that had been responsible for his time in the wilderness, that, the conservative hierarchy. Winston was very, very quick to forgive the people that he knew would be necessary to help win the war and Randolph couldn’t bear that, he couldn’t bear that he’d been excluded, that his loyalty hadn’t been rewarded, and he couldn’t bear that the things that had made him so useful and necessary to his father, his pugnacity, his willingness to pick fights, his bravery, his recklessness, all of that was the last thing in the world that his father needed.

His father needed someone calm and steady like Clementine, and Randolph didn’t help his case, he got… He’d get drunk and lose important maps when he parked outside Downing Street or he’d… All of the stories come back to Randolph being drunk and shouting at his father, he’d berate him about strategy over dinner. I don’t think he could ever adjust to the fact that he was no longer an important person, he wasn’t a partner of his father, he was just the Prime Minister’s son, and that doesn’t carry any weight.

Brett McKay: Yeah, these arguments, he would do it in front of the generals and Randolph would actually… He had no regard for hierarchy, military hierarchy when he was in his father’s presence and he’d just dress down generals and say, “You’re doing your strategy wrong,” and accuse people of cowardice.

[chuckle]

Josh Ireland: I mean it’s bold and it’s brave and it’s funny, and I’m sure a lot of those generals were really pompous and at the time the war was going really badly, so their strategy was probably wrong, whether Randolph knew any better is open to question but… Yeah I just think he couldn’t find a way of being useful to his father and so he just let go, he didn’t have any control. He wasn’t able to control himself, he wasn’t able to reconcile himself to the fact that he was this spare part now. And I think the thing he found intensely frustrating, and I think it’s impossible not to feel sympathy for him, was that Randolph knew that Winston revered bravery above everything, almost any other quality. And he was desperate to be able to get to the front line to fight, to show how brave he was and to secure his father’s admiration, but Winston was never willing to let him do that. He would say that if Randolph were killed, he wouldn’t be able to carry on as Prime Minister, so he found one way or another to stop him from going to the front. So Randolph was just a staff officer, kicking his heels, unable to contribute anything meaningful, unable to do anything that would make you stand out, and he became angry and bitter, and he took it out on the only person that he knew to do, and that was his father.

Brett McKay: And his father also, during the war would find excuses for his son to meet him somewhere, when Churchill was flying somewhere in the theater of war. He would somehow figure, “Oh I need Randolph here for whatever reason,” and Randolph would show up and I mean… What do you think was going on… Why do you think Churchill felt like he needed Randolph by his side?

Josh Ireland: I think Randolph was probably the most disruptive presence in Winston’s life. He caused trouble, he caused arguments, he got drunk, he picked fights, but he also understood him in a way that I think nobody else did. They had spent so much time that they kind of inhabited almost the same mental space. They had talked about the same moments from the past, they had gone through so much together already, they shared so many of the same opinions and views on the world, they liked to drink and they liked to gamble. And I think Winston found his son’s company a huge support, which is something that I don’t think anyone around him ever quite understood or appreciated. I think they, all they saw was this whirlwind who was gonna come in and break apart their carefully laid plans, but actually I think there was… Randolph actually was essential to his father’s well-being and his ability to relax in a way that enabled him to prosecute the war so relentlessly and so effectively. He needed that outlet and Randolph was that outlet.

Josh Ireland:And Randolph understood that Winston would want to start the day in bed in silk and dressing gown, smoking and drinking and for Randolph that was absolutely normal, whereas for tightly buttoned civil servants, it was intolerable. And was just more sympathetic, and I think probably right through Randolph’s life he gave his father the affection and unstinting admiration that Lord Randolph had never given Winston. And when Winston needed that, that’s when he picked the phone up and said, “Send me my son.”

Brett McKay: So something that added some more complication between the relationship between Churchill and Randolph, was Randolph got married to his first wife, Pamela. This is kind of an interesting thing ’cause it also, there was implications it had effect on the war a bit. So can you tell us about Randolph’s relationship with his first wife Pamela, and Pamela’s relationship with Churchill?

Josh Ireland: Yeah, the marriage should have been a really good thing. Randolph knew that two things would please his father once the war broke out. One was that he would fight with distinction and bravery, and two that he would find someone he could marry and produce an heir. Winston was absolutely obsessed with the idea of creating a dynasty of Churchills. So, absolutely central to that was the idea that Randolph should produce a son of his own. So Randolph wasted absolutely no time, almost within the weeks of war being declared, he proposed to, I think, seven women and all of them said no. Including, he was having an affair with two women at the time, both of whom said no. And then found seven unsuspecting debutantes who also said no. I think his reputation preceded him. And then finally he found someone who did say yes. Pamela was from another aristocratic background, maybe a tiny bit more provincial than the Churchill’s, and I think she was desperate to escape promised to be for her a boring, routine existence in the backwaters of England. For her, the Churchills was a passport into this exciting, gilded, glamorous political world.

Josh Ireland: So they married, a few months later, she gave birth to a child, Winston, and on the face of it everything was quite happy. Pamela and Winston got on incredibly well. She was brilliant at anticipating his moods, she soothed him when he was overwatch during the most tense times in the war, and he adored the fact that she had produced another heir. Unfortunately, all of the faults that have made Randolph a difficult son also made him an appalling husband, and when his own son was being born, he was in bed with the wife of another man, had to be summoned back from London at 4:00 in the morning, and he carried on drinking, he carried on cheating on her, he carried on gambling. And so it all came to a head when finally, he got posted to the Middle East and on the ship on the way over, he managed to lose their entire… I think he lost maybe four years’ worth of salary and then sent her a pathetic note saying, “I made a bit of a mistake. Do you think you could sort it out?” Which I think was the moment when I think she felt as if their marriage came to an end.

And that coincided with the arrival of Averell Harriman in the United Kingdom, he was President Roosevelt’s special emissary to Churchill. He was the person that would determine how much support the States, which still hadn’t entered the war, would provide Britain, which was looking increasingly beleaguered and alone, and war that was beginning to look unwinnable, and there was an immediate spark of attraction between Averell and Pamela. And Winston I think, recognized that that relationship had a value to him, that having someone who was so close to the man, who was in turn so close to President Roosevelt, might help him achieve his war aims, whether by persuading Roosevelt to send more men and ships…. Or more ships and munitions and supplies or just having someone who could engage in pillow talk, who could find out what the Americans were thinking. I don’t think for a second he initiated the relationship, but I think he knew it was happening and I think he encouraged it. He certainly never showed any sign of disapproving of the fact that his daughter-in-law was sleeping with another man.

Brett McKay: And what complicated the relationship even more is that Randolph and Averell, they became pretty good friends while Harriman was having an affair with Randolph’s wife.

Josh Ireland: Yeah, I think they were enchanted with each other. I think they had a great time. Randolph was stationed out in the Middle East at the time and Averell made a tour of Egypt and they spent hours in each other’s company. They went on boat trips. They went to restaurants. Randolph unwisely told Averell about all the affairs he was having in the Middle East, which I don’t know whether maybe that made it easier for Averell when he got home, but he seemed pretty comfortable in that deception. And I don’t think Randolph ever particularly… I don’t think he ever really blamed Averell for it, what had happened. I think he thought… He saw himself as a man of the world. He thought it was beneath for men to argue about women. What he resented, what he bitterly resented and what caused the wound that would probably never ever heal was his sense that his father had betrayed him. That was something he couldn’t bear.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So yeah, Randolph and Pamela end up getting divorced, and you make the case that that really harmed the relationship between Churchill and Randolph, ’cause Randolph just, for the rest of his life, pretty much felt that Churchill was responsible for it, like he knew about it and he took Pamela’s side or his side.

Josh Ireland: Yeah, I think he always felt as if… Not only did Winston condone that relationship and I think Randolph would have accused him of actually being the person behind it. Randolph, I think he just, he couldn’t ever get over it. Even years later, when Winston was this frail, old, weak person sitting on Aristotle Onassis’s yacht, Randolph would still be berating him. He’d be screaming in his face. It was something that cut Randolph deeply and no matter how many times he tried to heal that wound, he could never quite staunch the blood. It would still have the capacity to hurt him decades later.

Brett McKay: And the thing that amazed me as I was reading, particularly during the war years, their relationship was that, okay, Churchill, he’s leading in World War II. But at the same… That’s a big undertaking, but at the same time, he’s got all this family drama going on. I’m just like, how is this guy doing this? How is he dealing with his son yelling at him, his wife being mad at him because he’s forgiving his son, he’s got this daughter-in-law… How did this guy do that without keeling over from a heart attack? I think most people would have just died.

Josh Ireland: I think one of the interesting things is a lot of the times, his biggest flare-ups with Randolph happened around the time of greatest tension in the war. So the terrible arguments they had after Randolph found out that Pamela had been cheating on him came just as the Japanese were rampaging through Asia in late 1941, early 1942. And there’s an appalling row they have in the summer of 1944, just after D-Day, when, although things were going pretty well, there was still a lot up in the air. So it’s difficult to know whether there was something in the atmosphere which threw them against each other even more aggressively. But yeah, I think it is extraordinary that amidst all of that chaos, Winston is still focused. I think that was one of his great gifts, and then he had this ability to sleep when he needed to. I think the best thing he did was to send Randolph to Yugoslavia as much as he could to get him out of the way. And I think he recognized the value of sleeping and eating and drinking and having time to do things that weren’t anything to do with the war, but I don’t think having your son screaming at you or your wife not talking to you is a recipe for functioning well at work normally, and even especially if you are running a war effort.

So yeah, it is extraordinary that in the days after D-Day, when you would have thought that all of his attention should have been focused on what was happening in Normandy or other parts or the far east, and he was thinking about his son. He was writing letters to his son. At precisely this time, Randolph was writing to his mother, begging Clementine to tell Winston to stop interfering in his marriage that he couldn’t help himself. As I said, he was obsessed by his son.

Brett McKay: So the war ended. Did their relationship get any better after the war?

Josh Ireland: I think the thing about their relationship before the war was that whether they were up or down, whether they were screaming at each other or hugging each other, their relationship was just unmistakably exuberantly alive. It was so living and so energetic, and that quality disappears completely after the war. I think that Winston, as I said, had always needed that love and affection that Randolph gave him, and he needed it during the wilderness years more than he ever had before. He was subject to so much criticism, so much ostracism, that he needed that support that Randolph gave him.

And then after the war, he’s this hero across the whole world. He goes into restaurants and people start cheering him. He goes into a French cafe and doesn’t have to pay for a drink, and he’s showered with money and awards and praise, and so he doesn’t need that from Randolph anymore. And I think also something essentially breaks during the war. It’s the distance that him becoming Prime Minister creates and also all the ferocious bloody rows they have together. And I think for a long time, Winston liked the energy that Randolph provided. He liked the banter and he liked the aggression, and he liked the arguments, and that’s what he thrived off. And then I think after the war, he was exhausted, and the last thing he wanted was that son bustling into his room, telling him what to do.

And you could see that although I don’t think they ever lost their love for each other or their capacity for affection, I think they stopped liking each other, and that’s heartbreaking. Winston starts spending time with his son-in-law, Christopher Soames, much more than he ever would his own son. He started almost shunning him. If you look at the visitor books at Chartwell, where Randolph had been a constant visitor before the war, he barely comes at all in comparison after it.

And there’s this really… There’s all these very sad story… This one terribly sad story, Randolph, on one of the rare visits he does make, he sees that his father has this wonderful collection of Mark Twain’s… I think signed by Mark Twain, that he just left molding in a cupboard. So he asks his father if he could have them and Winston doesn’t really say anything. And then that night, it starts raining. Randolph is just having a walk after dark, and then he sees his father clad in a raincoat, carrying a towering pile of Mark Twain books, off to go and hide them from his son. It feels symbolic of where their relationship was after the war.

Brett McKay: We’ve been talking about, earlier on, since Randolph was a boy, Churchill had these aspirations that he would be a great man, be prime minister even and kind of create this Churchillian Dynasty, and Winston believed it and then Randolph believed it. Was there a point where both of them eventually resigned themselves to the fact that Randolph wouldn’t amount to much?

Josh Ireland:Yeah, I think Winston realized sooner than Randolph. I think Winston knew, as soon as the war has over. Randolph had been in Parliament for five years over the course of the war and then lost his seat in the 1945 election, which was the last time he would ever be in Parliament and I think Winston knew then. I think Winston knew that his son’s flaws were too deep and his anger was too great and he drank too much, he caused too many arguments. He’d fallen out with almost everyone in the Conservative Party’s hierarchy.

Randolph, I think, held onto that dream for longer. I think he felt that all it needed was for his father to disappear from the scene, whether that was to die or to walk away. I think he thought that as long as his father occupied a central place in British politics then there would never be space for him, which I think was true, but I think it also allowed him to believe that what happened to him wasn’t his own fault and that at some point, everything that he thought would happen would magically appear.

And the sad thing is that actually, it’s only when he lets go of that dream in the late ’50s that he actually begins to approach something like happiness. I think when he realizes that that pressure has been lifted, that he doesn’t need to think about that anymore, then he can begin to enjoy life for what it is rather than for what his father says it should be.

Brett McKay: Yeah, you talk about it… I think a big moment for Randolph with his relationship with his father… There was all this distance between them after the war. Randolph’s dream, since he was a boy was to write Winston’s biography. And he never asked his father to do it ’cause he’d think that’d be presumptuous, but eventually Churchill asked Randolph to write his biography. What did that mean to Randolph and how did that change the relationship?

Josh Ireland: I think it meant everything to him. It was a sign Winston did, in fact, believe in him and value him. And I think it, more than that, it offered his life a purpose that it hadn’t had before. It allowed him to have a part in shaping his father’s legend, the memory of his father, and it allowed him to become closer to him because he was given all these incredible documents from his father’s life. He was able to go and talk to people who’d been significant figures in Winston’s life. And I think that whole process allowed him to re-acquaint himself with a man that he’d loved so hard and so long for so many years. He would say it was the only worthwhile thing he did, and I think it brought him a happiness that had eluded him for decades.

Brett McKay: It’s like a happy melancholy because, alright, so he had these aspirations to be a great man, ’cause his father basically told him that he’d be a great man. But it ended up… He did do something great. There’s this quote, I’ll read it, that you quote him, he says… About the biography. He says, “It’s a monument to my father and I’ll have left something worthwhile, something worthy of me. I’ve never done that before. It’s nice to leave something behind that someone will remember.” So he did this great thing, but it was about his father. It wasn’t even him.

Josh Ireland: Nothing is ever purely his own. Everything he has always comes from his father in some way, that he can never really claim to have achieved anything on his own merits, which I think is crushing when you look back at your life and you think that. I think for anyone, I think you want to feel as if you’ve established your own identity or you earn everything that’s come your way. And for all the people, I think poured scorn on Randolph for always taking money from his father or taking advantage of Winston’s connections, I think he would have been so much happier if he’d have been given a clearer run at life, if he’d have been left to his own devices. He would say that everything good he did, people would say, “Oh, that’s only because of his father” and anything bad he did, they’d say, “Oh, how terrible for the old man.”

He was just locked in this golden cage and it’s no wonder that he began to resent it, because I think clearly, anyone who’s the child of a great person, that you’re forever trying to be judged on your merits, that you want to be compared to yourself, you don’t want to just be always compared in relation to what your father or mother or sister or brother may have done many years ago. And then you’re… And I think more than anyone, Randolph was trapped in there.

Brett McKay: As you wrote this book and looked at their relationship, did you get any takeaways about lessons on the father-son dynamic that are universal to all father and sons?

Josh Ireland:I mean, yes. So about a month after I finished the first draft, my wife had a baby, so it was one of those things that… It was a girl, but I think it was one of those things that really focuses your mind, you think about it. You’re much more alert to all those things than maybe you would have been otherwise. And I think one of the things that people criticize Winston for most is that sense that he over-indulged Randolph, that he left him spoiled. But I think it’s difficult to reproach someone for loving their child too much, I think much more damaging was the way he imposed his own ambitions and his own values on Randolph. He never even considered whether Randolph might want to do something other than become a politician or he never really wondered whether Randolph wanted the life that Winston was pushing upon him.

And I think that’s one thing I think, that you… No matter how much you might want something for your child, you have to let them find their own way, you can’t force them into something that you… Just because it’s important to you, it may not be important to your own child, and I think… I don’t think he can help this, but his personality was so strong, so he was so charismatic and so so powerful that I think Randolph, he couldn’t ever see himself outside of his father’s eyes. I think his own self-worth was entirely dependent on how his father was treating him on a given moment. I don’t think he ever had an independent sense of self.

So I don’t know quite how that translates into a universal rule for parenting, but I think what Winston could never respect was someone else wanting something other than the life Winston had wanted for himself, but at the same time, he was affectionate and generous. And I think the thing that is most admirable was his constant ability to forgive no matter what Randolph did, he always forgave him.

Brett McKay: And do you think it’s possible for someone to do world-altering work, great work that will be remembered for the ages and be a good father, or is that you had to choose one or the other?

Josh Ireland: I mean it’s interesting, if you think about all the great, The Big Three, the summits between Stalin and FDR and Winston Churchill through the war, these three immensely powerful men, who as much as anyone in history have really changed the course of history. They really had… They were extraordinary giants of men. And all of them had incredibly unhappy children, there’s a brilliant biography of Svetlana Stalin, who had this weird life where she actually ends up in the States, and she was completely crushed by Stalin. All of FDR’s children were unhappy. Randolph’s sisters, one of them committed suicide. Another basically drank herself to death. And I think to go back to where we began, the idea that great men need to be damaged in their childhood to go and do great things, I think the dark side of that is that they… Because they are damaged, they are able to do great things, but they are damaged and damaged people generally end up damaging the people around them, whether they intend to or not. And so, I think it is very hard to imagine anyone who is the child of a great person ever having a happy or fulfilled life because there are very few examples of anyone that has managed that.

Brett McKay: The one thing I always think about too, is you look… Here in America, there’s these families that were dynasties like the Roosevelts, for example. So we’re talking about the Franklin Roosevelt side and the Theodore Roosevelt side. None of their kids… I mean, Theodore Roosevelt, Teddy, Theodore Roosevelt Jr was, he became a general in the army. The rest of the kids, they had unhappy lives too. So it was always like, man, should you even try to go for great things if it’s gonna destroy your family? I’d love to figure out someone who’s able to go through that Charybdis and Scylla, and navigate through it. I don’t know if it’s possible.

Josh Ireland: I remember when I was young, I worked with… I won’t say who it was, but I worked at a publishing house, and we published a memoir by a child of one of Britain’s prime ministers, and they were just one of the most unhappy people I’d ever met. And they spent their entire life wanting approval or attention from their parent and had never been given it. And I think I always had that in the back of my mind as I was writing this, that you’ll always… That you can’t have both things that I think… Logistically, if your parent is a significant politician, the demands on their time and attention are immense, but I think also, the people that go on to do those things are egotistical and ruthless and selfish, and that’s what enables them to get to the top, but it also means that they are [0:49:35.4] ____ parents.

Brett McKay: Well, Josh, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Josh Ireland: Yes, so the book’s out in the States and in the UK, it’s published by Dutton, so it’s available everywhere, I’m sure.

Brett McKay: Well, Josh Ireland, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Josh Ireland: Well, thanks so much, Brett, I really enjoyed that. Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest here is Josh Ireland, he’s the author of the book, Churchill & Son. It’s available on Amazon.com and book stores everywhere, make sure to check out our show notes at aom.is/churchillandson, where you can find links to resources when you delve deeper into this topic.

[music]

Brett McKay: Well, that wraps up another edition of The AOM Podcast, check out our website, artofmanliness.com, where you’ll find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles written over the years about pretty much anything you think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of The AOM Podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium, head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code Manliness at check out for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of The AOM Podcast.

And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcast or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing this show with a friend or a family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for your continued support, until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to The AOM Podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.