For nearly two hundred years, the private detective has been a literary archetype of manliness.

Edgar Allen Poe invented the literary detective with his character Auguste Dupin. Sherlock Holmes is perhaps the most famous of literary sleuths. (You can find the 10 best Holmesian stories here). These detectives, and other private investigators of the 19th and early 20th centuries, showcased keen observation and sharp analytical deduction. You rarely saw them get into physical altercations. They were heroes because they were brilliant.

But in the 1930s and through the 1950s, a new type of private eye started popping up in American literature. These detectives were smart, but they were also physically and emotionally tough. If they needed to, they’d resort to violence. They also did their best to develop a kind of mental armor to protect themselves from the sleaze they encountered because of their work. This resulted in their having a cynical and detached view of life.

These detectives had to become “hardboiled.”

Dashiell Hammett is credited with creating the hardboiled detective with the character of Sam Spade. Raymond Chandler added his spin to the archetype by introducing the world to Philip Marlowe.

What all hardboiled detectives have in common is that they’re outsiders. They work to solve crimes, but do it because they’re hired to perform a job. They’re not officers of the law, though criminals often see them that way. They’re mercenaries. Renegades. Liminal characters stuck between two worlds. Consequently, the hardboiled detective often doesn’t have a given code of ethics to follow. He has to develop his own and fight like hell to stick to it.

For the last couple years, I’ve been reading and enjoying numerous works from the hardboiled detective genre. While these books are known as pulp fiction, and they are indeed engaging, non-overly-high-brow reads, there are also deeper existential currents going on under the hood. So you can read them as gritty page-turners, and also as musings on how to make your way in a chaotic, crooked world.

Below I share five of my favorites; if you’re looking to dive into the genre, they’re all can’t-go-wrong starting places.

The Difference Between Hardboiled and Noir

Genres are funny things. They can cause a lot of debate among fans. The world of detective novels isn’t immune from that dynamic.

Hardboiled and noir are often used interchangeably to describe the same type of book. While hardboiled and noir novels do share similar characteristics (an unflinching look at violence against a backdrop of human depravity), many aficionados make a distinction between the two. The best description of that distinction that I’ve encountered comes from noir author Megan Abbott:

“The common argument is that hardboiled novels are an extension of the Wild West and pioneer narratives of the 19th century. The wilderness becomes the city, and the hero is usually a somewhat fallen character, a detective or a cop. At the end, everything is a mess, people have died, but the hero has done the right thing or close to it, and order has, to a certain extent, been restored. . . .

Noir is different. In noir, everyone is fallen, and right and wrong are not clearly defined and maybe not even attainable.”

I’ve read my fair share of noir novels, and I’ll do a post highlighting my favorites within that genre in the future. For this article, I’ll just be focusing on hardboiled detective novels.

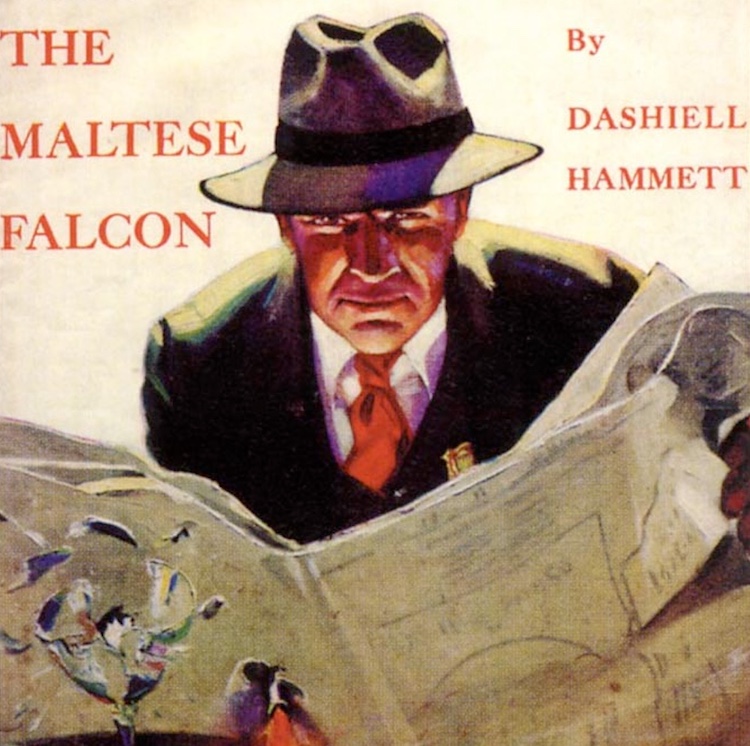

The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett

Dashiell Hammett created the pattern for the hardboiled detective with Sam Spade. Underneath Spade’s hardened and cynical facade lies a profound idealism — a commitment to live by his own code of ethics.

The Maltese Falcon begins with Spade’s long-time partner getting killed and the police fingering Spade as the primary suspect. Spade has to juggle proving his innocence while trying to hunt down a valuable statue of a bird. Featuring grifters, crooked cops, and a femme fatale with ever-shifting loyalties, The Maltese Falcon is a hardboiled detective novel you’ll have a hard time putting down.

Farewell, My Lovely by Raymond Chandler

Farewell, My Lovely is the second installment in the Philip Marlowe series but is considered Chandler’s best work.

It’s easy to see why.

The story is actually several stories woven together into one. It starts out with Marlowe witnessing the murder of a club owner by a felon looking for his old girlfriend. You think this will be the main story you’ll be following in the book, but the narrative then shifts to Marlowe hunting down the thief of some stolen jewels. You subsequently think that’s going to be the main mystery Marlowe will solve, but then the story finds him diverted once again, and trying to bust a phony psychic and a drug-dealing doctor. That might sound like a confusing jangle of plotlines and loose ends, but it doesn’t feel discordant, and in the end, Marlowe discovers that all of the mysteries are connected in one grand meta-mystery.

Throughout it all, Marlowe lives by his personal code of honor and does his damndest to neither be seduced by wily femme fatales nor corrupted by all the crooks he encounters.

I’ve read most of the Marlowe novels, and this one is by far my favorite.

The Thin Man by Dashiell Hammett

Nick Charles is a former private eye who spends his time drinking and wisecracking with his socialite wife, Nora. Charles reluctantly comes out of retirement to start investigating the murder of the secretary of a really messed-up family.

What makes The Thin Man such a great read is that the Charles character is completely different from Hammett’s other detective creations, and from other PIs in general. Charles is definitely a hardboiled guy. Thanks to years of working among humanity’s lowlifes, he’s tough and cynical.

But there’s also a lightness to him.

He doesn’t take life too seriously, and you see that play out in his relationship with his wife, Nora. They really do love each other, and they really enjoy each other’s company. The best part of the novel is watching them sling witty banter and dialogue back and forth.

Devil in a Blue Dress by Walter Mosley

When black people show up in old hardboiled detective novels, they’re usually crime suspects or minor characters.

Walter Mosley broke that mold by creating a black private eye: Easy Rawlins. We’re introduced to Easy in Devil in a Blue Dress.

Like his white counterparts, Easy has to navigate a world where he’s an outsider. He’s not a police officer, but he’s also not a crook. He’s different even from many of the other private investigators in the genre, in that he has no background in law enforcement; untrained and unlicensed, he gets into detective work as an amateur.

But there’s yet another layer to Easy’s role as an outsider: he’s a black man living and working in 1940s Los Angeles. He has to navigate the racial tension and animosities that exist in mid-20th century America.

In Devil in a Blue Dress, we see Easy take on his role as a hardboiled private eye and how he gets the job done in the face of all the opposition he encounters. And like all other PIs, he has to do so while maintaining his own code of ethics and honor.

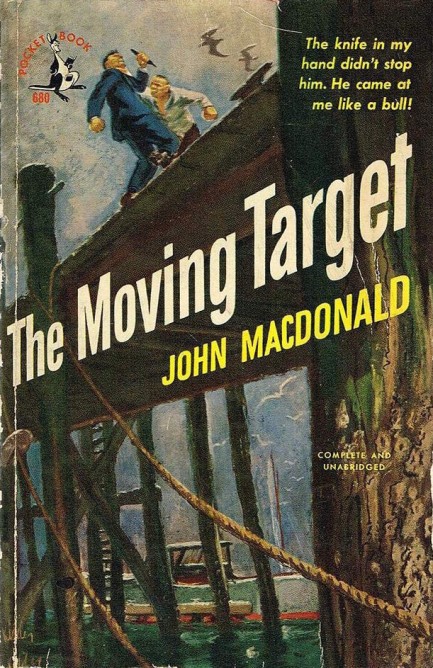

The Moving Target by Ross/John Macdonald

In The Moving Target, Ross/John (both pen names for Ken Millar) introduces his hardboiled private detective, Lew Archer. Like Marlowe and Spade, Archer is a hardened and world-weary guy (though he’s got more of a sensitive and sympathetic strain) who’s just trying to make it in his line of work without compromising his ethical code.

In his literary debut, Archer is hired by a paralyzed wife of a millionaire to find her missing husband. To solve the case, Archer must deal with the flirtatious daughter of said millionaire, an aging Hollywood film star, a sinister British crook, an addict jazz singer, and a cult leader.

Seamlessly constructed and thoroughly engaging, The Moving Target is my favorite out of all the hardboiled detective novels I’ve read.