Welcome back to our series on the libraries of great men. The eminent men of history were often voracious readers and their own philosophy represents a distillation of all the great works they fed into their minds. This series seeks to trace the stream of their thinking back to the source. For, as David Leach, a now retired business executive put it: “Don’t follow your mentors; follow your mentors’ mentors.”

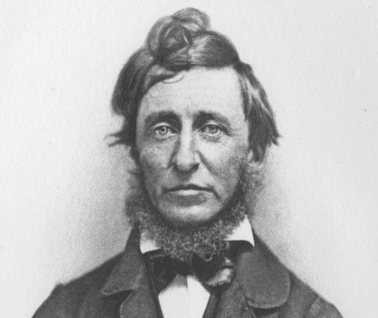

Thomas Jefferson is best known for being the 3rd President of the United States and drafting the Declaration of Independence. And for good reason — these monumental tasks are enough to get any man into the annals of American history. Amazingly, though, Jefferson didn’t stop there. After his presidency, he took on the work of re-creating education in the young country. Up until that point, education was largely a religious undertaking from youth all the way through university. Jefferson, however, believed that one’s education should encompass much more than just knowledge of the divine.

So, in 1819, at the ripe age of 76 years old, he founded the University of Virginia as a secular institute. At the center of this undertaking — quite literally — was the library. Traditionally, the chapel would be at the center of campus. At UVA, though, Jefferson put the library in the center of campus, thereby signaling his belief that books were central to one’s education.

It would be easy to imagine Jefferson as a stuffy reader, but he was quite the opposite. He actually found history and ethics to be fairly dull:

“Thus a lively and lasting sense of filial duty is more effectually impressed on the mind of a son or daughter by reading King Lear, than by all the dry volumes of ethics, and divinity that ever were written.”

He was well-versed in all disciplines, but works of fiction were perhaps his favorite:

“A little attention however to the nature of the human mind evinces that the entertainments of fiction are useful as well as pleasant.”

Throughout his life, Jefferson was a habitual writer of letters, and he frequently responded to requests from strangers for lists of books and ways to improve oneself. In one particular letter, he responds to the commonly held belief of the time that one could only be educated in virtue through Greek and Roman classics:

“Everything is useful which contributes to fix in the principles and practices of virtue. When any original act of charity or of gratitude, for instance, is presented either to our sight or imagination, we are deeply impressed with its beauty and feel a strong desire in ourselves of doing charitable and grateful acts also. On the contrary when we see or read of any atrocious deed, we are disgusted with its deformity, and conceive an abhorrence of vice.”

In that letter, as well as many others, Jefferson gave a lengthy list of books that he found to be uplifting for both moral gain as well as pleasure. What’s listed below is a sampling of the books that Jefferson mentioned in various letters throughout his life. He even went so far as to often organize them by category, so I’ve done the same.

As Jefferson himself noted, these works don’t encompass the entirety of what a man should read, but will provide an excellent base:

“These by no means constitute the whole of what might be usefully read in each of these branches of science. The mass of excellent works going more into detail is great indeed. But those here noted will enable the student to select for himself such others of detail as may suit his particular views and dispositions. They will give him a respectable, an useful and satisfactory degree of knowledge in these branches.”

Thomas Jefferson’s Recommended Reading List

| Title | Author |

| Ancient History | |

| The Histories | Herodotus |

| History of the Peloponnesian War | Thucydides |

| Anabasis & Hellenica | Xenophon |

| Life of Alexander the Great | Quintus Curtius Rufus |

| The Gallic War & The Civil War | Julius Caesar |

| Antiquities | Josephus |

| Lives | Plutarch |

| Annals & Histories | Tacitus |

| History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire | Edward Gibbons |

| Philosophy | |

| Works of Plato | Plato |

| Works of Cicero | Cicero |

| Morals | Plutarch |

| Moral Epistles & Essays | Seneca |

| Memorabilia of Socrates | Xenophon |

| Meditations | Marcus Aurelius |

| The Enchiridion | Epictetus |

| An Essay Concerning Human Understanding | John Locke |

| Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion | David Hume |

| Candide | Voltaire |

| Introductory Discourse and the Free Inquiry | Conyers Middleton |

| Nicomachean Ethics | Aristotle |

| Literature/Epic Poetry/Plays | |

| The Iliad & The Odyssey | Homer |

| The Aeneid | Virgil |

| Paradise Lost | John Milton |

| Oedipus Trilogy | Sophocles |

| Orestian Trilogy | Aeschylus |

| The Plays of Euripides | Euripides |

| Poems | Horace |

| The Works of Shakespeare | William Shakespeare |

| The Misanthrope | Moliere |

| Gulliver’s Travels | Jonathan Swift |

| A Modest Proposal | Jonathan Swift |

| Don Quixote | Miguel de Cervantes |

| The Adventures of David Simple | Sarah Fielding |

| The Adventures of Roderick Random | Tobias Smollett |

| The Vicar of Wakefield | Oliver Goldsmith |

| Tristram Shandy | Laurence Sterne |

| The Canterbury Tales | Geoffrey Chaucer |

| Poems | Edmund Waller |

| Politics/Religion/Modern History | |

| Spirit of the Laws | Montesquieu |

| Two Treatises of Government | John Locke |

| Discourses Concerning Government | Algernon Sidney |

| The Bible | |

| The History of America | William Robertson |

| Historical Review of Pennsylvania | Benjamin Franklin |

| A History of the Settlement of Virginia | Captain John Smith |

| Science | |

| On Electricity | Benjamin Franklin |

| The Gentleman Farmer | Henry Home |

| The Horse Hoeing Husbandry | Jethro Tull |

| Buffon’s Natural History | Georges-Louis Leclerc |

| Anson’s Voyage Round the World | Richard Walter |