The western story, in its most usual forms, represents the American version of the ever appealing oldest of man’s legends about himself, that of the sun-god hero, the all-conquering valiant who strides through dangers undaunted, righting wrongs, defeating villains, rescuing the fair and the weak and the helpless — and the western story does this in terms of the common man, in simple symbols close to natural experience . . . depicting ordinary everyday men, not armored knights or plumed fancy-sword gentlemen, the products of aristocratic systems, but ordinary men who might be you and me or our next-door neighbors gone a-pioneering, doing with shovel or axe or gun in hand their feats of courage and hardihood. —Jack Schaefer

The West has always held a strong place in the American psyche. From the earliest days, west represented the frontier of this nation. Whether it was Kentucky and Ohio or Colorado and Montana or Oregon and Alaska, as a people we’ve always moved westward. And once we crossed the Mississippi, we found a harsh environment unlike any other. Deserts and oases, flatlands and mountains; it was a land of environmental and climatic extremes.

It was in this land that the legend of the cowboy was born, particularly in the mid-to-late 1800s. As Western writer Jack Schaefer notes above, the cowboy embodied strains of the ancient chivalric code, but he wasn’t the aristocratic knight-in-shining-armor of England or even the pious, settled farmer of early America; rather, he was a kind of everyman hero: a regular man who yet was more autonomous, independent, and free than an ordinary fellow. Riding atop his trusty steed, he knew both how to protect others and how to survive himself, and evinced a taciturn, brass tacks, self-made nobility.

Odes to the American cowboy, in the form of the Western novel, started taking shape in the early 1900s, a decade after the U.S. Census Bureau declared that the frontier was closed; the books captured a nostalgia and romantic yearning for an era and way of life that was on its way out (and in some ways, never really was). Western novels mixed real-life detail with larger-than-life drama, as all great mythologies do.

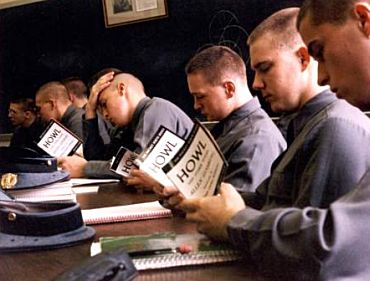

The genre was easy to mass produce, and until the 1940s or so, the Western dime novel led the way. Quality writing and quality stories were hard to come by (though as you’ll find below, a few gems did make their way out into the public sphere). It was in the late ‘40s, and on into about the mid-’70s, where Western literature really came into its own. Louis L’Amour, Jack Schaefer, Edward Abbey — this was the era in which legends were born.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, there was a bit of a downturn in the genre, though a couple lone outstanding works were produced. The ‘90s especially were a black hole, but then the 2000s and even through today have seen a bit of a resurgence in the genre. The old tropes of cattle drives and small town shootouts were played out, so writers started taking some more risks with storylines that have really paid off. I would say that we’ve actually entered another golden era of the Western in the last 20 years or so. Even though the sheer volume of works put out isn’t as great, the quality has tended to be superb. Mainstream publishers are leery of Westerns, so what ends up getting printed is rather good.

Over the last year or so, I’ve read through the canon of what’s considered to be the cream of the crop for Western literature. I consumed dozens of books, and have here narrowed them down to the best 21 that every man should read. I gave each author just a single book on the list (though I do mention other titles I enjoyed for certain authors) because I’m of the opinion that it’s better to read broadly in the genre than to dive whole hog into the works of just one fella. If you’ve read a couple L’Amour titles, you’ve read them all, and the same can be said for a number of other authors.

The list below encompasses all manner of styles, book lengths, storylines, etc. Before getting into it, though, we need to define the genre.

Defining the Western Genre

Simply being set in the West does not a Western make; if so, novels like East of Eden or Angle of Repose would be found here. While not every novel will satisfy every marker, each book listed here includes most of the following elements:

Geographically set west of the Mississippi River. While some very early Westerns are set in the likes of Kentucky and Ohio, the geography that really captured readers’ attention and defined the legend of the cowboy lies west of the Mississippi: Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Montana, etc. Also, Westerns don’t generally reach the West Coast.

Schaefer said this about the geographic setting of his genre:

The bigness beyond the Mississippi was primarily open bigness, beckoning bigness — and also a violent, raw, capricious bigness: extremes of topography and climate beyond those of the east, the highest and lowest areas of the entire nation, the hottest and the coldest, the flattest and the ruggedest, the driest and the wettest.

Takes place during the 19th century. The 1800s, and particularly the mid-to-late 1800s, was really the period of the Western frontiersman and cowboy. While the Machine Age was coming in the East, the West remained wild and untamed. Plenty of Westerns are set in the 20th century, but most on this list take place during the 1800s.

Characters are cowboys, ranchers, homesteaders, gunfighters/sheriffs/rangers, and/or frontiersmen. The career of a Western character is pretty limited, and centers on the aforementioned roles. To come West in the mid-to-late 1800s was generally to be one of those things. Horses also tend to play a large role and often, although not always, faithfully accompany a Western novel’s human characters.

Focus is often given to the harsh, but beautiful landscape. The land itself often plays a role as a main character in Westerns. Long descriptions of the environment are common, and nature’s obstacles — drought, storms, mountains, wild animals — frequently play a role in the main conflict or storyline. Main characters also tend to deeply care for and respect the wilderness and what it represents; even when hunting or ranching on the land, the men fight to preserve what’s natural and spurn the advances of modernity.

Contains characters who show skillfulness, toughness, resilience, and vitality. Whether cowboys or ranchers, the characters who populate Western novels typically share a common constellation of traits and qualities.

One is the possession of a broad, hard-nosed skillfulness. Cowboys and other Western types are adept at everything from roping and riding to hunting and cooking. They’re at home in a wild environment, and what they don’t have at hand, they can improvise.

Western characters also possess a notably flinty character. Schaefer again:

If there is any one distinctive quality of the western story in its many variations, that quality is a pervasive vitality — a vitality not of action alone but of spirit behind the action . . . a healthy, forward facing attitude towards life.

Westerns that contain the elements listed above invariably tend to have this less definable element present as well. It’s almost a byproduct of writing strong characters in a harsh landscape. Great Western novels are permeated with a sheer masculinity and spiritedness that’s hard to find in other genres.

21 Western Novels Every Man Should Read

Given the above set of criteria for inclusion, and selected for overall excellence in plot, characterization, readability, and so on, here are my picks for the best Western novels ever written, arranged chronologically by their date of publication:

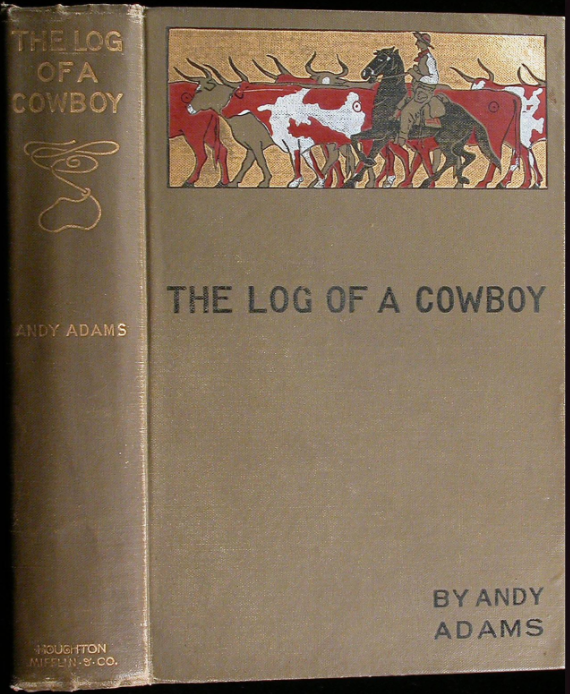

The Log of a Cowboy by Andy Adams (1903)

Among the short list of very early Westerns (pre-1910 or so), you’ll often see Owen Wister’s The Virginian (1902) at the top. I didn’t find that title very readable though, and in fact gave up about halfway through. The Log of a Cowboy, on the other hand, was remarkably readable and easily held my attention the whole way.

Pulling together various real-life stories and anecdotes (including from his own experience of being a cowboy for over a decade), Adams chronicles a fictional Texas-to-Montana cattle drive through the eyes of young Tom Quirk. There isn’t much in the way of overarching plot or a central conflict, but it’s enjoyable nonetheless. From cattle runs, to brutal dry spells, to dangerous river crossings, to hostile Indians and outlaws, the reader really experiences all that an Old West cattle trail had to offer. And that includes the minutiae of paperwork, hours of boredom, how guard duties were divvied up, etc. Adams’ narrative is often considered the most realistic depiction of a cattle drive there ever was, and he in fact wrote the novel out of disgust for the unrealistic cowboy fiction being written at the time.

A hair dry, but recommended reading for any fan of Western novels. If you have any doubt about its place in the canon, you’ll quickly see how much Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove was inspired by Adams’ early novel; the outline of the plot is basically the same.

Riders of the Purple Sage by Zane Grey (1912)

Grey was the early king of the Western dime novel. His output was prolific, but the more he wrote, the more negative reviews he received from critics. (Critics are always skeptical of folks who seemingly write too much!) I don’t think those criticisms have merit, as I find much of Grey’s work to be eminently readable and entertaining today, especially given that most of his work was published over 100 years ago.

Riders of the Purple Sage, published in 1912, is definitely the best of the bunch, and is universally found on “Best Western Novels” lists for a reason.

A more complex plot than is often found in Westerns, the story follows Jane Withersteen, and her harassment at the hands of a group of Mormon fundamentalists. Elder Tull wants to marry Jane, but she refuses. As you can imagine, that’s when the trouble starts up, and she needs help from friends Bern Venters and a mysterious gunman named Lassiter who’s searching for a long-lost sister. There are a number of threads here, and some excellent plot twists. Again, it’s more complex — in a good way — than what you’d normally see in the genre.

Required reading for the fan of Western novels. Grey’s short stories/novellas are also very good (“Avalanche” being my favorite — though it’s a little hard to find).

The Ox-Bow Incident by Walter Van Tilburg Clark (1940)

Cowboys Art Croft and Gil Carter have ridden into Bridger’s Wells, Nevada to find a charged atmosphere. Cattle have been disappearing (likely stolen) and a man named Kinkaid has just been murdered. The townsfolk are mad as heck and looking for justice. Factions form almost immediately; one group wants to capture the suspected culprits on the up and up — to get the judge and sheriff involved and make sure no untoward behavior happens. Another group wants to form a posse to go after the rustlers — vigilante-style — and take care of business with Wild West justice: a hanging at sunrise. They argue that using the legal system takes too darn long and that too often men get off scot-free.

A posse indeed forms and eventually catches up to the alleged rustlers. Are the men lynched? Are they given a chance at a fair trial back in the town of Bridger’s Wells? Are they set free?

While not as fast-paced as many Westerns on this list, the morality tale encased within its 80-year-old pages remains remarkably relevant. It’s an ethics discussion about mob mentality clothed in cowboy flannel and leather holsters. While other Western writers of the era — like L’Amour and Grey — could be said to romanticize the West and its heroes, Clark is more comparable to Dashiell Hammett. All the characters, protagonists and antagonists alike, have deep flaws, and the reader can’t quite decide who he’s siding with, if it’s anyone at all.

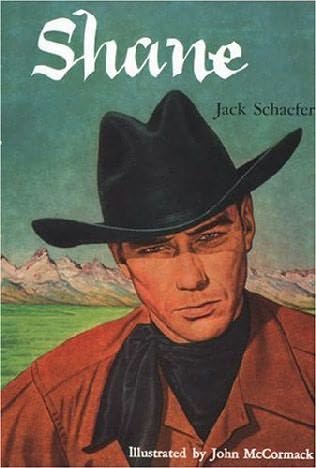

Shane by Jack Schaefer (1949)

Shane is considered by many the best Western novel of all-time. It’s compact, but that just means every page is stocked with virile energy — much like Shane himself, the book’s main character.

Narrated by young Bob Starrett, the story follows his version of events in a small outpost in the Wyoming Territory. Seemingly out of nowhere, the mysterious Shane (Is it his first name? Last name? Made-up name?) rides into town on the back of a horse and takes up temporary residence at the Starrett home. Shane becomes close to the family, and Bob especially comes to see the rider as a mythical, godlike figure. Meanwhile, cattle driver and all-around bad dude Luke Fletcher is trying to take land from a group of homesteaders (the Starretts included). I won’t give away anything else other than to say that Shane is involved in the bad guys’ dispersal.

The pure masculinity of the novel, and of Shane himself, is unrivaled in Western literature. If you aren’t stirred by this novel, you don’t have blood running through your veins. Shane is absolutely a top 3 Western novel. Schaefer’s Monte Walsh is also superb.

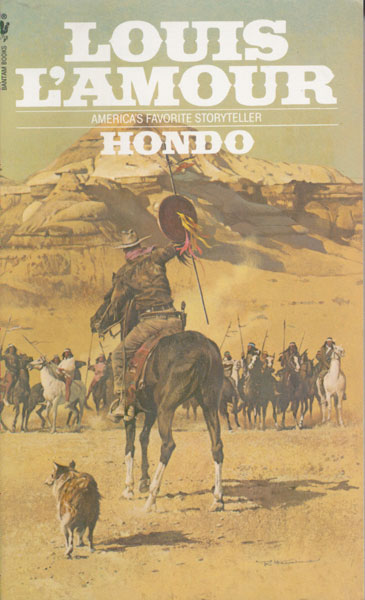

Hondo by Louis L’Amour (1953)

No mention of Western novels is complete without a nod to L’Amour. His books alone could keep you reading for about a decade at a pace of one a month. I read a handful, and have to agree with most others that Hondo is his best. Interestingly, the John Wayne film came first, and L’Amour then novelized that (although the movie was inspired by a L’Amour short story — it’s a bit circular).

Hondo Lane is a quintessential man of the Southwest, shaped as much by the desert landscape as anything else. A former cavalry officer, Lane has had to learn the Apache ways in order to survive in the harsh environment. After escaping an ambush, he comes upon the homestead of Angie Lowe and her young son, with the husband and father nowhere to be found. Throw the warrior Vittoro into the mix, and you get a dramatic story of love, war, and honor that is as representative of the Western genre as a story can be.

Now, with the sheer number of titles he produced, L’Amour’s stories admittedly tend to run together a bit. They’re also slightly formulaic, and you wouldn’t really classify his writing as lyrical or Pulitzer-worthy. But, his books are just really entertaining. It’s like how the Fast and Furious movies aren’t going to win any awards, but I’ll be damned if I’m not watching every one of ‘em for their sheer entertainment value.

Kilkenny and The Tall Stranger were a couple other L’Amour favorites for me.

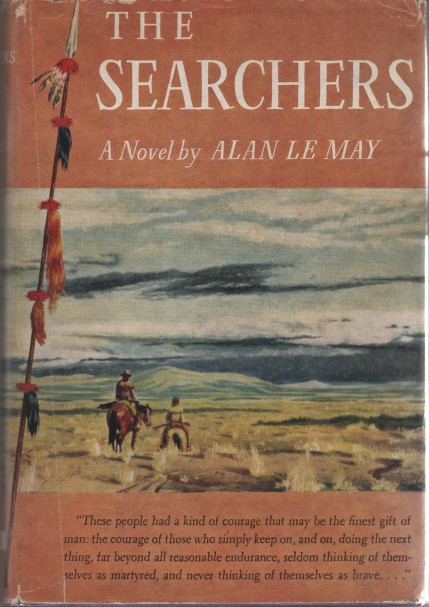

The Searchers by Alan Le May (1954)

If there’s a Moby Dick story to be had in this list, it’s Le May’s The Searchers. While the movie is often seen as one of the greatest Western films of all-time, the book deserves its place of recognition as well.

With one of the most devastating openings on this list, a Comanche raid destroys the entire Edwards family, killing the men folk and kidnapping the women. What follows is a years-long quest by Marty (a virtually-adopted young man who’s part of the Edwards family) and Amos (the Edwards’ patriarch’s brother) to find the missing women. If you’ve seen the movie, you know roughly how the rest of the tale goes, and if you haven’t, I won’t give away anything else.

The book deserves a place on this list because of its sprightly and realistic writing, but also because it portrays the difficulties early homesteaders had in trying to make a life on the oft-dangerous frontier. While indeed some Native Americans were harshly portrayed as violent savages, the reality is that many were indeed incredibly violent and didn’t take kindly to new people settling in their territories.

The Brave Cowboy by Edward Abbey (1956)

Edward Abbey is a legend of environmental, anarchist, and Western writing. He penned essays, novels, and non-fiction works, including Desert Solitaire, which makes an appearance on a number of Best Non-Fic Books of All-Time lists.

The Brave Cowboy indeed falls into the Western novel category, but it’s also more than that. Particularly, it’s a lament of how the modern world — which was the 1950s at the time of the book’s writing — is taking something away from our lives and perhaps more importantly, from our lands. The era of jet planes and city streets was taking over.

Cowboy Jack Burns is a roaming ranch hand in 1950s New Mexico who refuses to join modern society. (The scenes of his horse — named Whisky — crossing highways and tentatively walking on pavement are rather memorable.) This alone makes it stand out from other cowboy stories, which are almost always set in the 1800s. Burns tries to break his pal Paul Bondi out of prison, but things don’t go quite as planned, and Burns ends up on the run with nothing but his guitar and his trusty steed.

From there, it’s a gripping cat-and-mouse story set in the desert. Abbey’s descriptions of the landscape are breathtaking and unmatched in Western literature.

Butcher’s Crossing by John Williams (1960)

In my opinion, Butcher’s Crossing is the most underrated book of the Western genre. You’ve probably never heard of it, but it should be on your reading list ASAP.

Considered one of the first to de-romanticize life on the frontier, the story is set in the 1870s and follows young Will Andrews, who has ditched Harvard, and been inspired by Ralph Waldo Emerson to come West in order to find . . . something. Meaning? Purpose? Himself? All the above, most likely.

Butcher’s Crossing is the small Kansas town he lands in before shortly thereafter joining a buffalo hunting expedition that heads into the mountains of Colorado. They deal with everything the Old West has to offer: extreme dehydration and thirst, early snowfalls, feisty animals (both domestic and wild), and raging spring-time rivers — all set within a merciless buffalo hunt (slaughter, really). Andrews learns some hard truths not only about the land, but about his own make up. But, he also does find something meaningful, and ultimately has to choose between going back East, or venturing even further West. I legitimately didn’t know what he’d choose to do until the very end (and I won’t tell you, of course), which is a sign of a superbly-written character.

Robert Olmstead’s recent Savage Country also takes on the buffalo hunt plot line, and while it’s rather good, Butcher’s Crossing was far better.

Little Big Man by Thomas Berger (1964)

Berger writes the fictional life story of Jack Crabb, who is our 111-year-old narrator. Crabb is thrust into Cheyenne Indian life as a young boy in the mid-1800s after his family is massacred while traveling west. From there, the story jumps back and forth between Crabb’s various forays in and out of the worlds of Indians and white men. Along the way, we run into numerous famed real-life characters of the West, including Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, and in particular, General Custer (Crabb claims to be the sole white survivor of the Battle of Little Bighorn).

It’s partially satire, but also rather accurately portrays both the unfortunate stereotypes ascribed to American Indians as well as the reality of their lives on the plains. There are plenty of hard-to-believe plot twists, but that’s part of the book’s semi-outlandish and epic nature.

It’s largely written as a narrative, with little in the way of dialogue, so it’s not a quick read. It’s extremely well written though, and in a more authentic voice than many Westerns are. It actually reminded me of Lonesome Dove in terms of its writing style — which is about as high a compliment as can be given.

True Grit by Charles Portis (1968)

Though the story has twice been turned into a feature film, it was Portis’ short 1968 novel which first introduced the public to two of the most memorable, and naturally, grittiest, characters in Western history: 14-year-old Mattie Ross and one-eyed US Marshal Rooster Cogburn.

An older Ross narrates the story of the time she sought revenge for the murder of her father. Young Mattie ventures to Fort Smith, Arkansas to find a man who would help her on this quest. She decides on Cogburn — who has a penchant for violence and a quick trigger finger — because she believes he has the “grit” to get the job done (which means, of course, the disposal of the murderer). Cogburn agrees, but is incensed when Mattie insists on coming along; he tries to lose her a number of times, but Ross displays her own tenacity and keeps right up.

The language and dialogue is almost over-the-top old-timey — and therefore comes across a little unrealistically (it does work especially well with this story for some reason, though!). Despite that, Portis writes some of the most memorable scenes of the entire genre. If you’re afraid of snakes, there’s one in particular that might haunt your dreams.

The Time It Never Rained by Elmer Kelton (1973)

Voted by his peers in the Western Writers Association as the greatest Western writer of all time, and recipient of a record 7 Spur Awards, Kelton authored a number of books that could appear on this kind of list. I read a handful, and thoroughly enjoyed each and every one; the best of the bunch, though, in my opinion, is The Time It Never Rained.

West Texas had suffered through droughts before, but nothing like the real-life destructive dry spell of the 1950s. Kelton tells the story of this drought through fictional aging rancher Charlie Flagg. As the drought gets worse with every passing season, nobody — from the Flores family (the loyal ranch hands), to twenty-something aspiring rodeo cowboy Tom Flagg (Charlie’s son), to local bankers and landowners, to the numerous Mexican migrants coming across the border looking for food and work — remains unscathed.

Ultimately, the townsfolk start either drifting away, or turning to the government for provisions. Flagg, though, a bit of a stubborn curmudgeon, spurns federal help and tries to stick to his self-reliance through it all. Will he make it through the drought, or will the harsh conditions force him to leave behind the only life he’s ever known? Not only does Kelton create relatable, memorable characters that you’ll find yourself rooting for, but he paints a vivid picture of the hold Mother Nature had on Western towns and families.

There are few writers whose entire canon ends up on my to-read list, but Kelton is one.

Centennial by James Michener (1974)

If you’re looking for a single book that encapsulates all of Western lit’s sub-genres, Michener’s epic, 900-page Centennial is the way to go. Although set in and named for a fictional northeastern Colorado town, the book actually begins well before any town is established. In fact, Michener begins with a chapter of the geological beginnings and even the dinosaurs of America’s western landscape. From there, each chapter covers an aspect of typical Western lit, all set in or around the town of Centennial: Indian life, hunters and trappers moving from east to west, battles between whites and natives, buffalo hunts, cattle drives, and more. Where Centennial goes further is its depiction of western life after the 1800s, when farming and small-town crime and Mexican immigration all come to play a part in daily life.

At 900 pages, it’s not a quick or necessarily easy read. (You might think that’d be obvious, but a tome like Lonesome Dove is in fact both quick and easy.) The nice thing, though, is that each chapter, although long, is only loosely connected to each other chapter. The novel roughly follows a family tree over the course of centuries, but the plot points differ and the chapters can in fact almost be read as short stories.

Indeed, Michener’s lyrical writing is magnificent, and it’s a joy to read a chapter of it every now and then (at least that’s how I did it).

The Shootist by Glendon Swarthout (1975)

How many different ways can the story of a Western gunman really be told? Glendon Swarthout took that challenge and created the exceptional tale of dying gunman J.B. Books.

Having been diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer, the nefarious gunfighter decides that he’ll spend his dying days in El Paso. The town is none-too-happy about his being there and tries to convince him to leave, but he stubbornly stays. Being an infamous man, various folks come out of the woodwork when word gets around that he’s dying in El Paso, including journalists hoping for a story and other gunmen looking to bolster their reputation by killing Books.

You’d think the story would perhaps be more about Books recounting his life stories, but it’s really just about those last few months and an older man trying to somewhat redeem his sordid reputation. And the way Books chooses to go out on his own terms at the end is as memorable a scene as you’ll ever come across.

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford by Ron Hansen (1983)

Hansen’s 1983 novel verges on true-to-life biography of the (in)famous bank robber Jesse James, and his assassin, young Bob Ford. Somewhat lacking in the way of action — the James Gang robberies are only briefly covered — it’s mostly a character study of the eccentric James, and his obsessive, devoted minion, Bob Ford.

It was only when Ford was convinced that James would kill him (and when the reward money became too high to ignore) that the 20-year-old killed James in his own home, while his back was turned and his gun holsters removed. Ford figured he’d be a hero, but while he was pardoned by the Missouri governor, he became a bit of an outcast. He was a terribly interesting figure himself, and in fact the final quarter or so of the book covers Ford’s life after the murder.

Hansen noted that he didn’t stray from any known facts or even dialogue; he just imagined some of the scenes and added more detail than was perhaps known. It’s not a quick read, but sure a good one.

Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry (1985)

There’s a reason I’ve often compared the other books on this list to Larry McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Lonesome Dove: it can readily be considered the Western against which all others are judged. Of the many dozens of books I read in compiling this list, Lonesome Dove was, without a doubt, the best.

The story is a seemingly simple one: two long-time friends — Augustus (Gus) McCrae and Woodrow Call, along with a ragtag group of ranch hands — embark on a cattle drive from the Rio Grande to Montana. Along the way they encounter outlaws, Indians, old flames, and plenty more. McMurtry takes 800+ pages to tell this story, but it’s so good that you’ll be rather sad when it comes to an end (which it will do far too quickly).

There are three other books in the series as well. While Lonesome Dove was the first and best of the bunch, the others are also great: Streets of Laredo (1993), Dead Man’s Walk (1995), and Comanche Moon (1997). Read them by internal chronological order if you’d like (in which case LD is third), but you don’t have to. I read ‘em in the order they were published, and I didn’t feel like I was missing anything.

If you read one Western in your life, make it Lonesome Dove.

The Revenant by Michael Punke (2002)

More survival story than true Western, but the setting — 1820s Wyoming and Montana — merits its place on this list. If you’ve seen the award-winning movie you know the broad outlines of the plot: After being savagely attacked by a bear, frontiersman Hugh Glass is barely alive. His comrades carry him along for a couple days, but he slows the group’s pace too much. They decide that Glass will die any day now, and leave him behind with two men who are tasked with caring for him until that time comes, and then burying him. The two men leave early however, taking all of Glass’s supplies. Against all odds, Glass regains consciousness, sets his own broken leg, and crawls/hobbles his way over 200 miles to the nearest outpost, even allowing maggots to eat his dead flesh in order to prevent gangrene.

While elements have certainly been embellished over the years, it’s based on an unbelievable true story. Unlike the movie version, which is largely fictionalized and diverts quite a bit from original historical accounts, the novel on which that movie is based stuck to them as much as possible, with just conversations and thoughts being imagined.

The scenes of primitive self-surgery, belly-crawling miles through hard terrain, and hunting and foraging with no tools whatsoever are the stuff of survival legend. It’s like Hatchet on steroids and for adults. While you’ll certainly read it quickly, the story won’t soon leave your mind.

No Country for Old Men by Cormac McCarthy (2005)

McCarthy has a number of Western novels that could qualify for this list, but my own favorite by far was 2005’s No Country for Old Men.

Unlike many Westerns on this list, it’s set in the relatively modern 1980s, on the border of Texas and Mexico. While hunting in the desert, Llewelyn Moss stumbles upon a drug deal gone bad, and claims for himself two million bucks he finds amongst the carnage. Of course, that missing cash isn’t going to go unnoticed, and almost immediately Moss is hunted by some really bad dudes, including one of the most terrifying villains in Western history, Anton Chigurh.

The best parts of the story, in my opinion, center around the aging Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, who investigates the crime and sets out to protect Moss and his young wife Carla Jean. As is a staple of the genre, Bell laments how things are changing in the West. He can’t keep up with the increasing, senseless violence. Can he manage to protect the Mosses? You’ll have to read to find out (or watch the excellent movie).

Perhaps surprisingly, I didn’t care for McCarthy’s near-universally-praised Blood Meridian, and although the Border Trilogy was enjoyable, I see No Country for Old Men as McCarthy’s can’t-miss Western.

The Sisters Brothers by Patrick deWitt (2011)

Eli and Charles Sisters — the Sisters brothers — are assassins who’ve been hired to kill a prospector in 1850s California. They’ve been told by their employer — the Commodore — that this prospector is a thief. Of course, the truth is a little more complex than that.

As with many Westerns, the Sisters’ sibling relationship is also complex. There’s jealousy, disdain, even anger. But ultimately, there’s a deep-seated familial love for each other. For a modern novel, the language deWitt uses — in the form of brother Eli’s narration — is surprisingly believable as coming from the place and time period. There’s also plenty of humor and misadventure to go along with the seriousness of the plot. It’s a good balance, and one that many of the best Western novels tend to find.

The Son by Philipp Meyer (2013)

Spanning a handful of generations of the McCullough family, the story is told largely through the lives of three main characters: Colonel Eli, his son Peter, and his great-granddaughter Jeanna.

The Colonel survived a Comanche raid as a kid and lived with the tribe for 3 years. When he returned, he eventually became a Texas Ranger, and then a rancher, and often feuded with the neighboring Garcia family. The son, Peter, is a disgrace to the Colonel because he’s soft and falls in love with a Garcia daughter. Jeanne spends many formative years with the Colonel, and she’s been the one to acquire his drive for business and empire. In her later years though, she contemplates who will take over the family business in a world that’s quickly abandoning its uses for cattle and oil.

It’s a history of the West, within a family epic set in Texas. It chronicles both the cowboy and rancher ways of the Old West, along with how that culture largely disappeared as the world modernized.

El Paso by Winston Groom (2016)

Winston Groom is most well-known for penning 1986’s Forrest Gump, as well as a treasure trove of masterful and wide-ranging history books. In 2016, for the first time in about 20 years, Groom published a new novel — a fantastic Western called El Paso.

It’s the story of a kidnapping in the midst of Pancho Villa’s Mexican Revolution. Villa takes hostage the grandkids of a wealthy railroad magnate, and what follows is a rollicking tale of an eclectic cast of characters trying to get them back. What’s great about the book is how many real life characters Groom peppers in: Ambrose Bierce (who has a fascinating story of his own), Woodrow Wilson, George S. Patton (whose auspicious start came in the Mexican Revolution), and a few other railroad tycoons.

The book really has everything: gunfights, romantic drama, an epic bull fight, a cross-country race between a train and an airplane, and some history lessons about America’s first armed conflict of the 20th century. It’s nearly 500 pages, but reads very quickly, and deserves a spot among the best Westerns of this new era of the genre.

Dragon Teeth by Michael Crichton (2017)

Taking on a forgotten aspect of Western exploration, legendary techno-thriller author Michael Crichton originally wrote Dragon Teeth in 1974, but it wasn’t published until just last year, almost a decade after his death. Set in the 1870s, the fictional story follows the real-life “Bone Wars” between dinosaur hunters Othniel Marsh and Edward Cope.

Back then, there was a lot of glory (and of course money) to be had in discovering dinosaur bones, particularly out West. This led to some ruthless rivalries, most notably between Marsh and Cope. In Dragon Teeth, William Johnson is a fictional Yale student who takes a summer to work for the two dino hunters (how he comes to work for not just one but both of them is for you to find out).

It’s a super fun, entertaining, swashbuckling story about a little-known aspect of the West. Beyond just cattle drives and buffalo hunts, the Bone Wars really captured America’s imagination and spirit of adventure.

Follow along with more of what I’m reading — from Westerns to old biographies and more — by signing up for my newsletter: What I’m Reading.

Tags: Books