Does the approach of the holidays fill you with a bit of dread?

Do they seem more like a forced march than occasions that are supposed to be joyfully anticipated and whose ostensible purpose is rest, celebration, and a break from the labors and banalities of one’s everyday routine?

Maybe there’s something wrong with our holidays, at least in their currently constituted form.

As Brian Earl, author of Christmas Past, explained on the podcast, while how we do our holidays (specifically Christmas, but really all of our holidays) seems eternal and set in stone — the way things have always been done and should be done — most of our current traditions are in fact quite recent; the majority only emerged and crystallized in the last 200 years. They have greatly changed over time and will continue to evolve into the future.

Evolutions in our holidays arise from the intersection of capacity and desire; changes, whether technological, cultural, or economic, make something doable, and that something becomes a tradition when it also scratches a societal need — it works for people, it makes sense to them.

For example, prior to the mid-19th century, Christmas was more of a public holiday — more akin to Halloween or the Fourth of July — than a private, domesticated one. It was celebrated with drunken revelry on streets and in town squares rather than in the familial living room. But with the rise of railways, people could both move farther away more easily, and more readily return home. And so Christmas became a time of homecomings, when the fragmented family could all get back together and reconnect around the household hearth.

Christmas only became a major shopping and gift-giving holiday relatively recently as well. The holiday’s heavy focus on exchanging presents was spurred by the rise of industrialization and the proliferation of material goods; as production outstripped demand, demand was inflamed by the rise of another new technology-facilitated phenomenon: print advertising. But this wasn’t simply a top-down dynamic, fueled purely by commercial interests; people were genuinely eager to procure the new trappings of the middle class, and there was real delight in seeing them sitting beneath the tree on Christmas morning.

Partaking in sweet treats at the holidays has a longer history, and yet was also created by the particular circumstances of history. During the Middle Ages, sugar, spices (like cinnamon, ginger, and cloves), and dried fruits (like raisins and figs) became more accessible in Europe due to trade, but were still expensive, and so were saved to elevate occasional festivities. Breaking out these rarer commodities at the holidays made these occasions feel special. When sugar and spices became more accessible during the Victorian era, sweets became an essential part of the holidays and were used to make cookies, candies, puddings, and cakes that still felt like novel indulgences in a time when diets were less varied, and there weren’t grocery and convenience stores on every corner, stocked with thousands of desserts and snacks.

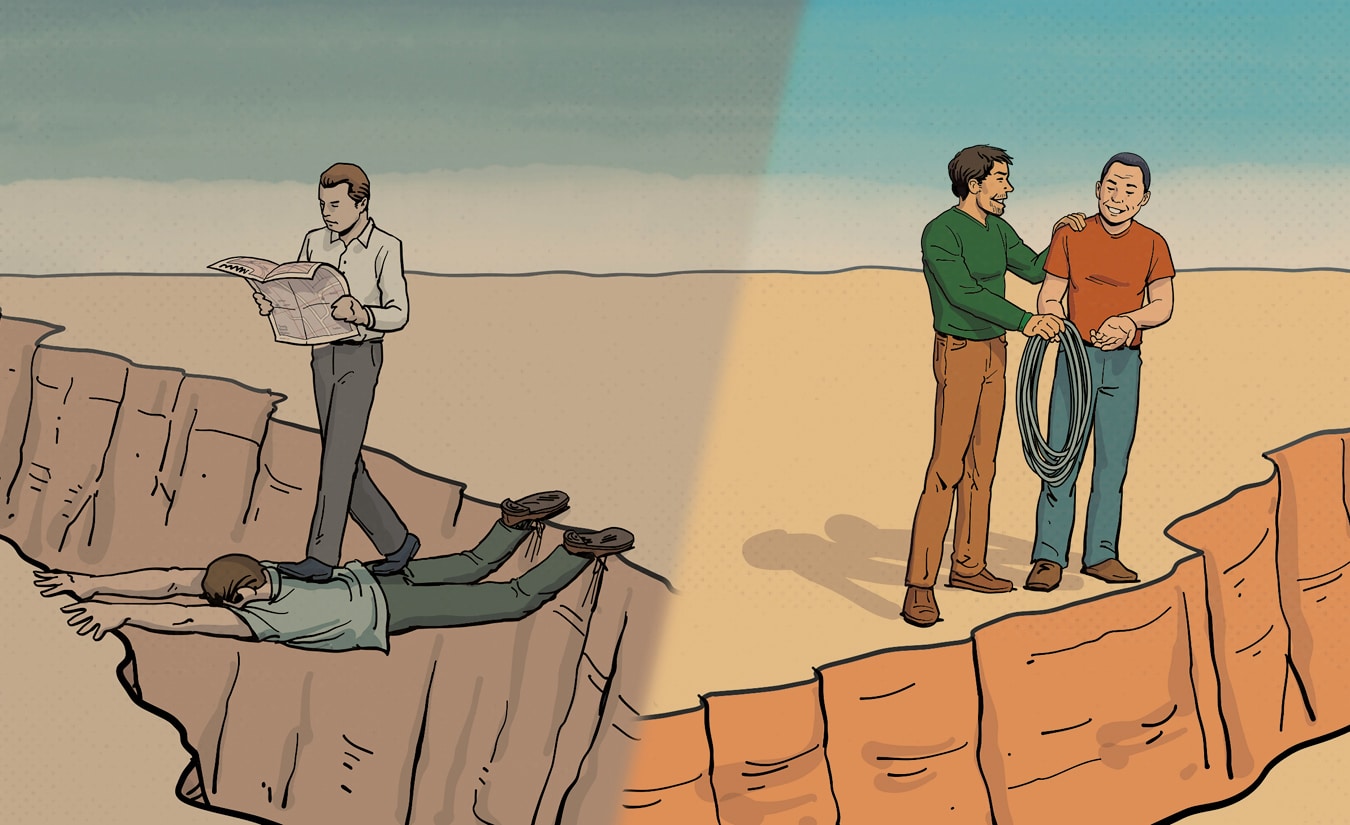

While much has changed over the last 150 years, we’re still in many ways living out the holiday traditions that were created a century and a half back. Unsurprisingly, while some of our traditions still resonate and generate joy, others seem thin and stale. We’re not sure why we’re doing what we’re doing, but we do it because it’s what we’re supposed to do. Born from the specific needs of a certain time, we live out traditions that no longer fit our own.

Brian Earl uses a metaphor from the historian Bruce David Forbes, who compares the evolution of holiday traditions to a snowball: “Roll a snowball, and three things happen. First, it grows larger as it accumulates snow. Second, it picks up pieces of anything else that lay in its path. And third, pieces periodically fall off as the mass of snow changes shape and buckles under its own weight.”

It seems easier to accumulate traditions than to slough them off, and we may need to help the process along, intentionally dropping some rituals and practices and replacing them with ones that meet the unique needs of our age — traditions that will help us refresh our spirits, recalibrate our perspectives, and celebrate those aspects of life that get neglected the other 360 odd days a year.

What Are the Holidays We Need Now?

What form might those new holiday traditions take? (While all of our holidays could use some revamping, we’ll here focus on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s.)

The possibilities are innumerable. These are just a few spitballed ideas:

Travel (somewhere different and fun) for Christmas. While Americans used to be a more mobile people, the number of folks who move each year has been declining for almost a century and hit the lowest level ever recorded, 7.8% of the population, in 2023. Even those who move don’t go far; only a fifth cross state lines. So while far-flung family members might have relished a Christmas homecoming in the 19th century, many people today already see their families fairly regularly. And, while a worker in the 1800s might have spent 12 hours a day, 6 days a week laboring in a factory, and thus relished a day off to luxuriate around the house, more people today work from home, and are already tired of and saturated with its surroundings.

Thus, it might make sense to create a tradition of traveling at Christmas. Not traveling to another family member’s house, but traveling either with your own immediate family or with your extended family to a location where no one necessarily lives. Somewhere fun and different.

To help fund this trip, you could decide to put the budget you were going to use for gifts toward your trip, because another tradition that could be introduced is:

Swap gift-giving for note-giving. When you start seeing holiday ads in October, does it give you a little pukey feeling inside? It’s not only a reaction to a premature start to the season’s crass commercialism, it’s a feeling of, “Man, nobody needs this.”

Getting gifts used to be more exciting when you didn’t know about the existence of certain products or where to get them, and buying things was an effortful pain that required going from physical store to physical store. It was neat to receive something you didn’t know existed and didn’t have to schlep to a mall to get for yourself.

Today, the online marketplace has put any and every product in the world at your fingertips, and with the click of a key, Amazon Prime will have it to your doorstep in just a day or two. Whatever you’ve wanted, you’ve probably already searched for and bought for yourself.

At the same time, today’s kids are less interested in toys than electronic devices and digital accouterments — things that are impossible to put in a stocking and less thrilling to find underneath a tree, than, say, a Red Ryder BB gun.

“Stuff” has lost its shine.

But even though the appeal of exchanging material presents has declined, there’s still something valuable that lies underneath the practice that’s worth preserving. In giving someone a gift, you have to think more intently about them than you typically do; you have to think about who they are and what they like. It pushes you to be a little more other-focused and a little less self-focused than you usually are.

That benefit might be replicated, while dropping gift-giving, by swapping the exchange of gifts for the exchange of notes. What about a tradition in which everyone gave family and friends a note that shared a favorite memory of the person from that year or something they appreciated about the person that year? Instead of opening up presents on Christmas morning, everyone would open up envelopes and get to read some life-affirming words.

Of course, grown-ups would be much more open to this idea than children. But children could be offered the idea of going on a trip in lieu of gifts.

Fasting (and physical feats) before feasting. From harvest rituals to religious celebrations, feasts have been central parts of holidays since time immemorial. But the satisfaction of eating your fill and then some was premised on the fact that your diet, outside of these special occasions, was otherwise more meager and plain because the circumstances of a hardscrabble life dictated that condition and/or because the liturgical calendar prefaced days of feasting with prescribed days of fasting. A day of indulgence was uniquely pleasurable because it was exactly that: a rare and luxurious loosening of restraint.

Today, almost everyone overeats, at least a little, every single day. We indulge in more sweets, treats, and diversified delicacies each week than our ancestors enjoyed in a lifetime. When the holidays come around, we don’t go from empty to full, but from full to bursting. It’s hardly a recipe for savoring and relishing our seasonal smorgasbords.

Yet, there is still something special about eating foods that only come around once a year, and the practice of cooking, of making things by hand when so much of what we eat is packaged and store-bought, seems like something that’s needful and still worth preserving in the modern day.

To maintain the benefits of homemade feasts at Thanksgiving and/or Christmas, while increasing their pleasure, we ought to precede them with a day of fasting and physical feats. What if folks abstained from food for 24 hours before these holidays? While fasting doesn’t seem “fun,” it adds meaning and texture to occasions, and when participated in communally, it becomes a bonding device. And, of course, as hunger is the best spice, it increases the taste and pleasure of the meal that breaks the fast.

To take people’s minds off the fast, while also increasing the meaning-making challenge of it, the day before/morning of Thanksgiving or Christmas could be filled with physical activities like races, obstacle courses, or hikes. Even our ancestors, who lived very active day-to-day lives, filled their holidays not only with rest, but sports, games, and dances. How much more do we moderns, who putter through extraordinarily sedentary existences, need holiday traditions that involve us exercising our bodies? If holidays are breaks from the norm, then what we desk drones need most are opportunities to move and play. And work up an appetite for the imminent feast!

Disconnect. In the 19th century, communicating with others was a challenge; hence the popularity of returning home for visits when you could and sending Christmas cards when you couldn’t. Even in the 20th century, long-distance telephone calls were expensive, and less common, so that calling your loved ones on Christmas was a nice, special gesture.

Today, we have the opposite problem. We often feel too connected. There’s never a time when you can’t be reached, and you’re ever inundated with texts and emails. The rare, needed commodity isn’t communication of any kind, but the face-to-face variety. We need a holiday from digital distractions and for the radical act of complete presence.

So how about a tradition in which everyone turns off their phones and devices at sundown on Christmas Eve and doesn’t turn them back on til sundown on Christmas Day? A holiday shabbat.

There’d be no Zoom calls with Aunt Myrtle on Christmas. You can beam into people’s lives any other day of the year; there’s nothing special about doing it on a holiday.

If you’re there, you’re there. If you’re not there, you’re not there.

There’d be no taking pictures on Christmas, at least with your phone, either. The only pictures that could be taken would be those snapped with an actual camera — you know, one that uses real film. In fact, when you turned off your phone and dropped it into a basket on Christmas Eve, you’d get to reach into another basket to take a disposable camera that would be your visual record-keeping device for the next 24 hours. Then you’d get the fun of having those photos developed later.

There’d be no checking Instagram to see how other people’s Christmases went and how yours measured up.

If you’re not there, you’re not there. If you’re there, you’re really, 100% there.

NYE regrets and hopes. From the beginning of time, holidays have frequently involved drinking and getting absolutely smashed. It made sense, at least for our ancestors. When you’re laboring as a serf on a farm or working 12-hour shifts in a mine, when you have time off, you want to forget about all the hardships of your labor-intensive, disease-ridden, death-filled, hardscrabble life and become completely numb to the world.

But in an era of unbelievable prosperity, a time of comfort and abundance that would have amazed anyone anywhere in the world up until a century ago, it makes less sense to use our holidays to become less conscious. The great need in our own time, when our material goods are abundant but our inner lives are impoverished, is to become more so.

In the modern world, we have the luxury of asking life’s big questions, but rarely take advantage of it. We need a holiday from putting out fires and exclusively thinking about day-to-day tasks; we need a time to actually think about our lives — what we’re currently doing with them and what we’d like to do with them.

So on New Year’s Eve, instead of getting sloshed, why not gather around a campfire with friends to share two things 1) A regret from the previous year (which can be written down on paper and tossed into the flame), and 2) A goal for the year to come.

———

While it might seem inconceivable that we could ever alter our holiday traditions in the ways described above, as Earl observes, holidays are far more malleable than we realize; “Our familiar version of Christmas would be barely recognizable to our ancestors, just as Christmas in the far future will only vaguely resemble that of today.”

Some classic, once-ubiquitous holiday activities like caroling and sending Christmas cards have already seen significant declines in the last few decades. Even the number of people putting up Christmas trees has decreased by a double-digit percentage. Earl thinks that in the future, even these “timeless” traditions will go extinct, “just as the day came when the Christmas tree replaced mistletoe and holly as the main Christmas decoration, or when serving a boar’s head for Christmas dinner became a historical relic.”

The holidays are always changing. They evolved more slowly before the rise of mass media, and more quickly after it, when images of how the holidays were supposed to be done could be standardized and disseminated across the country and the world. Today, we’ve perhaps reached a point of tradition stagnation because we’re waiting for the kind of externally-dictated mass shifts that marked the last couple of centuries. But we no longer live in the era of mass media; we’re increasingly residing in our own niches. So rather than waiting to be swept up in a tide of cultural change, perhaps we should re-embrace the more localized, regional forms of traditions that existed before industrialization. Perhaps we should find traditions that work best for our particular communities, and even just our particular families.

As we do so, it can be tempting to make a clean sweep of things, to throw most everything out in the name of simplification. But the desire to simplify can sometimes just be a cover for laziness. The creation of fun, meaningful texture, and lasting memories always requires effort and inevitably involves some stress. The idea is not to get rid of effort-requiring traditions altogether, but to replace those that seem stale and pointless with those that are genuinely looked forward to and generate real joy — traditions where the effort feels worthwhile.

Exactly what holidays we need now is up for debate and may come down to personal taste, but one thing is for sure; the last thing we need in our modern age is more empty, forgettable days that are just like all the rest.