Even if you’re not very into jazz, you probably know Kind of Blue, the jazz album that’s sold more copies than any other and is widely considered one of the greatest albums ever, in any genre.

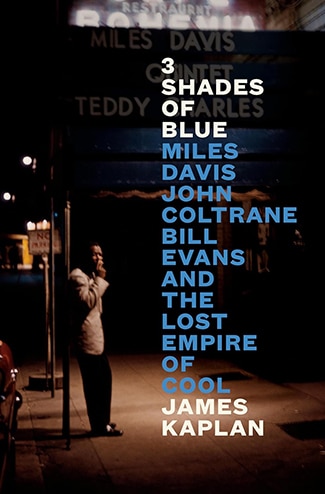

Among the sextet of musicians who played on the album, three stand out as true jazz geniuses: Miles Davis, Bill Evans, and John Coltrane. Today on the show, James Kaplan, author of 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool, unpacks the stories behind these towering figures. We discuss their background, their demons, their passion for musical greatness, and what they contributed to the evolving world of jazz. And we discuss why, when they got together to record Kind of Blue, the result was the most timeless and beloved jazz album in history.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- James’ last appearance on the AoM podcast: Episode #186 — The Legend and Reality of Frank Sinatra

- “Miles Davis Blows His Horn” — James’ 1989 Vanity Fair profile of Davis

- AoM Article: A Crash Course in Jazz Appreciation

- AoM Article: Want to Get Into Jazz? Listen to These 10 Albums First

- Albums mentioned in the show

Connect With James Kaplan

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art Manliness Podcast. Even if you’re not very into jazz, you probably know Kind of Blue, the jazz album that sold more copies than any other, and is widely considered one of the greatest albums ever in any genre. Among the sextet of musicians who played on the album, three stand out as true jazz geniuses; Miles Davis, Bill Evans, and John Coltrane. Today on the show, James Kaplan, author of 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool, unpacks the stories behind these towering figures. We discuss their background, their demons, their passion for musical greatness, and what they contributed to the evolving world of jazz. And we discuss why when they got together to record Kind of Blue, the result was the most timeless and beloved jazz album in history. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/blue.

Alright, James Kaplan. And welcome back to the show.

James Kaplan: Brett, I am thrilled to be here. Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: So we had you on a few years ago to talk about your biography of Frank Sinatra. You got a new musical biography out, and it’s about the artist who created one of the most influential, most popular jazz albums of all time, and that is Kind of Blue, headed up by Miles Davis. What led you to take a deep dive into the artists behind this album?

James Kaplan: Well, truth be told, I had lunch with my editor a few years back, and we were talking about what book I might do. I had had a suggestion for a book idea, which went nowhere. I won’t tell you what it is. [chuckle] But he had a comeback, and his idea was, “What about a book about Kind of Blue?” And I love Kind of Blue, and I had Kind of Blue, and I, like so many other people, was crazy about the album. But there is a wonderful jazz writer named Ashley Kahn who wrote the definitive book about that album, but it’s more of a technical book and more of a jazz book. Strictly a jazz book.

And what occurred to me when my editor, Scott Moyers, proposed this idea was, tickling around in the back of my mind was this amazing thing that I had in my pocket, Brett, which was that in 1989, when I was a young pop of a reporter, I snagged an incredible assignment from Vanity Fair to go and interview Miles Davis, and this was on the occasion of his about-to-be publication of his new memoir, then new memoir, called “Miles,” and I wangled my way into this interview. Actually, my brother helped me do it. My brother, the late newspaper editor, Peter W. Kaplan, great editor of the New York Observer, Was talking to this editor at Vanity Fair, who was looking around for a writer for Miles Davis profile, and my brother, my wonderful brother, said, “Well, my brother, Jimmy, knows everything there is to know about jazz,” [chuckle] which was an exaggeration, to put it very mildly. I knew nothing whatsoever. I had maybe three jazz albums at that point.

But Vanity Fair sent me, and with my knees knocking and my heart thumping, I rode up the elevator to the 17th floor of The Essex House, Central Park, South New York City, and walked into the apartment of Miles Davis. And I was terrified, because his reputation preceded him, but he turned out to be a total pussycat. And despite the fact that I knew absolutely nothing, I managed to get through an hour talking with him, and then he asked me to come back. And so I had the piece I did for Vanity Fair and these years ago recordings I did with the great Miles Davis, and I thought, when Scott, my editor, proposed this book about Kind of Blue, I thought, that’s interesting, but what about a book about the three geniuses of Kind of Blue? There were six musicians, but three of them arguably geniuses. Miles and John Coltrane and Bill Evans, what about those three guys before, during, and after the recording of that great album? What about writing about them not only as musicians, but as men? And Scott heard that, he loved it, and we were off to the races.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I’m glad you went down that route of doing a biography of these men, because I love reading biographies of great musicians, ’cause I find it incredibly inspiring. I know you did a biography of Irving Berlin. And Irving Berlin, the thing that inspired me about him was how much of a workhorse this guy was. He was just cranking stuff out all the time. And that was a big takeaway for me. A lot of success in life if you’re a creator of, whether you’re a writer or a musician, it’s just putting out a lot of stuff.

James Kaplan: It’s not just putting out a lot of stuff, but it is having the courage to fail. Irving Berlin wrote 1500 songs, and he’d like to say, “I wrote more bad songs than anyone.” [chuckle] And it’s true. He wrote a lot of bad songs. And John Lennon, Paul McCartney wrote bad songs. And Miles Davis made bad recordings. All these guys had artistic skeletons in their closet, but they all were incredibly hard workers. Miles and Coltrane and Evan’s practiced and practiced and practiced until their fingers practically bled.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I’ve been reading a biography of Bach. That was another workhorse. That guy was just constantly putting out stuff. And like you said, he failed a lot. We don’t know about all those bad stuff that you wrote, but you wrote a lot of bad stuff, but we remember the good stuff.

James Kaplan: His disco period, it’s a little no. Yeah.

Brett McKay: Alright. So I think to understand what makes Kind of Blue so singular, we have to do a bit of jazz history, and we’re gonna have to condense this. And it’s gonna be hard to do, ’cause jazz is a very multi-faceted art form. But I think the short story is, before the 1940s, jazz was primarily dance music. You went to a jazz band so you could dance to it, whether it was a Charleston or the Lindy Hop, whatever. But after World War II, you started to see the shift away from jazz as dance music to jazz as more of just an art in and of itself. Who were the musicians leading this shift away from jazz as dance music, and what innovations did they introduce?

James Kaplan: Right. And the thing I really wanna do here, Brett, is I want to avoid any… I don’t wanna put anybody to sleep. I don’t wanna talk about the snoozy history of this or of that. What I would like anybody listening to imagine is I’d like them to think about the greatest rock musicians, the greatest rap musicians they can think of. I want you to think about young, in this case, almost all young men. There were certainly women in jazz, but few. But I want you to think about young guys, primarily, young, Black guys, back in the 1930s. And this happened, actually, before World War II and during World War II. This new music called bebop sprang up. There was a recording ban for various reasons. There was a strike during World War II, and so the origins of bebop didn’t get recorded.

But I’d like you to think about these amazing young, Black guys, brilliantly gifted, guys like the guitarist, Charlie Christian, the saxophonist, Illinois Jacquet, Lionel Hampton, the vibraphonist, and in particular, trumpeter, Dizzy Gillespie, and alto saxophonist, Charlie Parker, those two guys. Young men, really young, and they’re really like rock musicians, they are full of juice, and they’re full of innovations, and they’re coming up with this new music that’s moving in a way that’s different to the way that jazz had moved before; different rhythms, different harmonies, wild and kind of angular. And these guys all played in conventional big bands, swing bands, before the war. And they would get in a certain amount of trouble with the band leaders, because they really wanted to play this new style of music, and the band leaders were making their money off of people dancing. So there began to be this kind of clash between these young turks and the old guard band leaders. And what happened during World War II was the big bands, the swing bands, got phased out. A lot of it had to do with wartime scarcity, no gasoline, the bands couldn’t afford to tour, there wasn’t enough money, the big bands began to go out of business, and suddenly, there were the small bands of these young turks playing this crazy new music called bebop.

Brett McKay: I think that’s an interesting point about the impacts. We often don’t think about this when it comes to art, we just think that, “Oh, an artist is just, they’re alone in their head, and they’re coming up with this stuff, but they’re being shaped by macro factors. And the economic factors of the Depression and World War II, that was driving… I mean, if it weren’t for the World War II and the Depression, we might not have had these innovations.

James Kaplan: Yeah. But we also need to think about these musicians struck by genius, as though they had been actually hit by pitchfork bolts of lightning; John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and Bill Evans. All guys born in the 1920s, coming up as young men and loving the music, the jazz that existed already, but full of their own weird ideas about where they could take the music.

Brett McKay: For those who aren’t familiar with bebop, how would you describe it? How is it different from, say, a swing song, like In the Mood? How would you describe that?

James Kaplan: Well, I would say that bebop is to big band swing music as Cubism is to impressionism, maybe, where you look at Cubist paintings, great paintings of Picasso and Braque, and you’re seeing something in the very early 1900s, something totally different from anything that had ever been done before. You’re seeing this angular, crazy-looking stuff on canvases. And at the time, people reacted violently against it. They just thought it was nonsense and almost sinful. It was so terrible-looking to so many people. It wasn’t beautiful. A lot of people had a similar reaction to bebop when it came in. You had this new music that was moving fast, that was moving in a crazy way, that was being played faster than jazz had ever been played before, that you couldn’t dance to. It had a beat, but you couldn’t dance to it. [chuckle] But a lot of young people and the people who weren’t absolutely set on dancing began to be fascinated by this new music. They would stand, and they would listen in awe as Diz and Bird, Charlie Parker, were playing these new bebop songs, and it began to turn into art music, began to turn into music that you could… As Dizzy Gillespie said, “You don’t necessarily have to dance to a song to really feel it. Sometimes you can hear a groove so strong it’ll make your back crack,” is what Dizzy said.

Brett McKay: And yeah, bebop, heavy on the improvisation. Swing, not so much. You’d have a little bit, but it was pretty much set, bebop, a lot of improvisation.

James Kaplan: Yeah. Bebop was, by definition, improvised. It was what they called “head arrangements,” arrangements memorized by the musicians and improvised on the stand. And it was very small groups. It was quartets, quintets, sextets at the most, playing in these little, tiny clubs on 52nd Street, the street as it was known. All these brown stones in the one block between 5th and 6th Avenue used to be speakeasies, turned into jazz clubs in the 1940s. And with these little, tiny, smoky clubs, little, tiny groups playing this wild, new music, you had a scene that had never been seen before and never been seen since. Bebop was really synonymous with New York City and synonymous with the street, with 52nd Street.

Brett McKay: As you said, I think it’s important to point out, these guys, they’re very driven, they’re very ambitious. And what’s interesting about jazz music, particularly bebop, it is collaborative. You’re working with a group. But at the same time, it’s almost competitor too. It was actually extremely competitive. These guys were always trying to outdo each other.

James Kaplan: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And a lot of that began in Harlem, at the great clubs, at the Savoy, at Mittens Playhouse with Thelonious Monk and Dizzy and Bird and Miles, played up there, and so many other great musicians. And yes, absolutely. There was this tradition called “cutting,” and one musician is playing up there in the bandstand, another musician would just jump up on there with the same instrument a guy had been playing and play his own solo and try and better him. And you could put the other guy to shame if you played better than he did. It was an accepted tradition, and it was not battle of the bands, it was battle of the players, and it was Darwinistic, determine who’s gonna come out on top.

Brett McKay: Yeah, sometimes those musical beefs turned physical. They’d actually get… There’d be fistfight sometimes with these guys.

James Kaplan: It was all really physical. It was all about sweat, it was about thrill, it was about excitement, it was about this music that nobody had ever heard before, and it was powerful, it was sexy, it was vital, it was brand new.

Brett McKay: Alright. So this period of the development of bebop jazz, this was the period where Miles Davis and these other musicians, who eventually were on Kind of Blue, this is when they came of age. This is when they were… This was the stew they were in when they were in their early 20s, when they were… The formative years. So I think we start exploring these individual members of Kind of Blue. Let’s start with Miles Davis first. He’s the coolest of the cool when it comes to jazz musicians. What’s interesting though, is that his upbringing was more affluent and conventional than a lot of people might think.

James Kaplan: Miles was well off, and there’s no two ways about it. Miles’s father, Miles II… Miles Davis that we know was actually Miles III, Miles Dewey Davis III. Miles’s father was a dentist. And as such, he was a professional man, well respected, successful, made money, had a horse farm. Miles grew up as a young prince. He rode horses at his father’s farm, he had beautiful clothes, he was a handsome, young kid, and his musical genius was recognized early. Miles had a unique upbringing, in that, it was so privileged. But at the same time, Miles knew that he possessed this strange and powerful gift of musical genius, and he knew he had to take it some place, and the place he knew he had to take it was New York City. He had to get there somehow.

Brett McKay: The way he got there, I think maybe this is how he convinced his parents to get him there, he was a student at the famous Juilliard School of Music. He got to Juilliard, which is very about formal music development. How did he go from there to becoming this jazz musician that we know today, that just added all these innovations to jazz?

James Kaplan: Miles’s father was very traditionalist, and he wanted his son to succeed in a traditional way, maybe even become a classical musician. And so Miles came up with this great strategy. The strategy was, “Let me go to New York and enroll at Juilliard, and I will develop myself and become an educated musician.” Well, [chuckle] there was a certain amount of deception in this strategy. What Miles really wanted was to get to New York City and to hook up with, to connect with Dizzy and Bird. He had met Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker in St. Louis, Miles’s hometown, when Bird and Diz came through playing with a band, and he wanted to get back with them, get to New York.

So he enrolls at Juilliard. He goes to New York City in 1944. He’s 18 years old. And after a couple of months at Juilliard, everybody around him is White, all the other students are White, all the teachers are White. And there was one day in particular in a classroom when a woman was teaching a class, started talking, holding forth about the blues and saying that Black people sang and played the blues because they picked cotton and they were miserable and they were down-trodden, and they had been slaves, and Miles finally couldn’t stand it anymore, and he stood up and he said, “Listen. I play the blues. I’m not down-trodden. I don’t play the blues because I’m down-trodden, and this stuff is all ridiculous.” Miles felt that he was learning from White people about White music, and to a certain extent, those lessons meant something to him. He was studying the great modernist, like Stravinsky and Shostakovich and Rachmaninoff, but Juilliard turned him off. And he got together with Dizzy and Bird as quickly as possible and very quickly got hired by Charlie Parker to join his band. An incredible thing. Here is this young kid out of the Midwest who everybody thought couldn’t play that well, but Bird heard something in Miles and hires him, and before long, Miles is playing great.

Brett McKay: Well, going back to this idea of the ambition of these men Miles Davis, he was super ambitious. And the way he got with Charlie Bird, he had to go look for him. He was constantly… He was on the prowl. He was hitting the pavement, trying to get in touch with Charlie Bird Parker, which just reminds me now when a lot of young men are young, they’re willing to just go and just relentlessly pursue, pursue, pursue, pursue, pursue until they get what they want.

James Kaplan: That’s exactly right. [chuckle] There was no internet, no Google, no Google Maps in those days. Charlie Parker, who was a major heroin addict and a major hedonist, was at large in Manhattan doing heroin, drinking, having sex with many, many, many women all over the place, there one night, here another night, sleeping wherever he felt like it, so he wasn’t that easy to track down. And Miles searched all over Midtown, searched the street, went up to Harlem, searched all over Harlem, couldn’t find Bird, then one night, he’s standing outside a jazz club and he hears a voice back of him and said, “Hey, Miles, you’ve been looking for me?” And it was Bird.

Brett McKay: Did Miles Davis drop out of Juilliard?

James Kaplan: He dropped out of Juilliard after one year. That was it for miles and formal education. But he really did keep on educating himself, and he took some of the lessons from Juilliard, again, listening to these great, modernists of Western classical music and the new harmonies they were bringing to the music. Miles, thought a lot about that, listened to a lot of it. So no more formal education, but for Miles from then on, it was the education of the bandstand.

Brett McKay: How did his father take him dropping out of Juilliard?

James Kaplan: Well, listen, another thing happened, which was that after World War II Miles went to Europe, went to France to play jazz, and found there a welcome that he had never found in the United States. Found white people who weren’t seeing him as a black man, but just as another human being, fell in love with this great singer, Juliette Gréco but then had to come back to the States and back to being a second class citizen, so depressed by coming back to having to be a black man in the America of the late 1940s that he fell into a heroin addiction. And Miles and his father, Miles went back home more than twice actually, to try and kick heroin. His father helped him with this but eventually, Miles had to do it himself. Miles’s father was disappointed that he dropped out of Juilliard. At the same time, Miles’s father understood that his son was a great musician and a troubled young man. He did his best to help Miles, but again in the end, miles had to do it himself.

Brett McKay: Going back to Miles Davis’s heroin addiction, heroin is a character that keeps reoccurring reappearing in your history, what was going on? Why was heroin such a heavily used drug amongst jazz musician during this time period?

James Kaplan: Before World War II, the drugs of choice among jazz musicians had been two. They had been marijuana, and a lot of songs about reefer in jazz prior to World War II and alcohol, of course. And a lot of musicians suffered from alcoholism and even died from alcoholism. During World War II, and especially immediately thereafter, a lot of heroine came into the United States. A lot of this had to do with organized crime. Suddenly there were pushers pushing heroine on jazz musicians. And then there was Charlie Parker. And Charlie Parker was the biggest heroine addict of all of jazz music. He was also a transcendent musical genius. And this awful myth arose, that among musicians, among young black and some white jazz musicians, that if you wanted to play like bird, you had to do like bird. In other words, if you used heroine, maybe you could achieve that transcendent high of musicians ship that Charlie Parker achieved. And it was a myth. It was this terrible falsehood, and a lot of guys died. But heroin addiction became widespread in jazz, right after World War II and stayed for about the next 15 years.

Brett McKay: Yeah. The way you described it the use, I mean, with Charlie Bird, he would sometimes just be passed out on the stand. And then when it was his turn to do his solo, he’d just get up and just crank it out like nothing was wrong. And then he’d go back.

James Kaplan: He was a phenomenon. He was an absolute phenomenon. He was a big strong guy. He had the constitution of a horse. But even in the end, Charlie Parker couldn’t overcome heroin. He didn’t die of overdose, but he really died of overuse of heroin. He died in 1955, at age 34. And when the coroner came to examine his corpse, he estimated Charlie Parker’s age as the mid 50s, 34 years old.

Brett McKay: Wow. So with Miles’ss heroin addiction, he goes from making it, becoming part of Charlie Bird’s Band. He becomes a success. Then he starts heroin and goes to being totally unreliable, nodding off on the stand when he was playing, when he did show up, his hair would just… Clothes would just be a mess. And that was a big change because before that, he took a lot of pride in his appearance, and sometimes he just didn’t even show up to gigs. I mean, he basically almost flushed his career down the toilet. But he did finally go cold Turkey on heroin, though he did continue to use cocaine and alcohol throughout his life. And that was partly to deal with some of the pain he had because he had sickle cell anemia. And he’s also just really brooding throughout his life. People called him the Prince of darkness, but when he put heroin behind him he became a more reliable artist.

We’ll take a quick break for a Word from our sponsors.

And now back to the show. So, when Davis has finally kicked heroin, this is when he started making a lot of the innovations to jazz that he’s famous for, during this time in the ’50s when he starts developing what’s been called cool jazz. How would you describe cool jazz? And then how did the jazz community initially receive these innovations?

Miles knew a guy named Gil Evans, this brilliant arranger and conductor from Canada, who Miles met on the street on 52nd Street. And in Gil Evans, he found a kind of a musical co-equal, a guy who loved the same kind of jazz and the same kind of modern western classical that Miles loved and Miles loved this guy. And they formed this very tight bond of friendship and musical friendship. And Miles and Gil Evans started to create this music together. Gil Evans was arranging this music. A lot of people were writing arrangements, were writing songs for a new kind of jazz that involved a lot of musicians, sometimes as many as eight or nine or 10 or more orchestras. But charts, written arrangements, and the kind of jazz that was something similar to what came to be known as Third Stream.

James Kaplan: It was almost a marriage of Western classical and jazz written down on charts. And the initial recordings that would later come to be called The Birth of the Cool were done by Miles in conjunction with Gil Evans, and were received early on, there’s no other word but to say coolly. [laughter] They were not met with warm affection by jazz musicians or by the public. The records didn’t sell at first. They weren’t even called the Birth of the Cool at first. And in particular, dizzy Gillespie was kind of scathing about this new arranged classical sounding jazz. He said that jazz was really meant to make you sweat. I don’t know if I can say this, I’ll say it anyway. Jazz was supposed to make you sweat in your balls, and this music didn’t make you sweat in your balls. A dizzy wanted a music that was improvised and not written down on charts, or if it was written down on charts, something that really had the power to, as he said earlier, to make your back crack, to be a strong groove. These were not strong grooves. They were smoother, they were cooler. And so it was a different branch of jazz, and it was an important branch of jazz, but not received warmly at first.

Brett McKay: Did it eventually get warmly received?

James Kaplan: It eventually became called The Birth of the Cool and Cool Jazz, and it was much admired by west Coast musicians. Jerry Mulligan, Chet Baker went out to the West Coast, became West Coast Jazz, and which became, very, very popular. Dave Brubeck out there. Cool Jazz achieved its own success during the 1950s, and especially after the fading of bebop, which really happened with the death of Charlie Parker in 1955.

Brett McKay: How did Miles Davis handle the cool reception to his innovation, like Dizzy Gillespie and these all the other guys, like he admired them when he was a young man. How did he feel like, “Oh, I got this new thing”, and everyone’s like, “This is not good.”

James Kaplan: Well, he was playing both sides of the street. He was playing the Cool jazz, and he was playing his own quintet and sextet jazz coming up with these great new innovations in jazz. As Bebop was starting to ebb, a new kind of jazz was rising up. And Miles not only was creating cool jazz, but he was one of the innovators of what came to be called hard bop. Now, hard bop in a certain way means absolutely nothing. What’s hard about it? What’s bop about it? It was a new kind of jazz that was much more soulful, much more based on gospel, on blues. People like Horace Silver, for example, came up, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. It was a jazz that was unlike bebop, which was like cubism. This was more deeply felt. It was more emotional, it was more bluesy. It was kind of a return to swinging and maybe you could even dance to a lot of it. So Miles was innovating both ways. And when you ask what his reaction was, Miles never particularly gave about what anybody’s reaction was to his music. Miles went his own way at all times.

Brett McKay: Constantly innovating. And what was his work ethic like? Was he just constantly performing as much as he could? Is that how he approached these innovations? Did the innovations come in practice, or did they really come out when he performed live?

James Kaplan: Miles was a guy, I’ll tell you a little story about Miles. Miles once was on the road with his quintet, and he heard late at night in the hotel, he heard one of his musicians practicing behind the door of his hotel room. Miles bangs on the door and barges into this guy’s room, and he says to this guy, “I pay you to practice on the bandstand, not in your room.” Miles wanted spontaneity. Now, this may sound paradoxical, he worked with Gil Evans on these arranged charts that were the birth of the Cool, but in the music that he played with his groups, with his small groups on the bandstand, he wanted everybody to be finding new ways right on the bandstand. So he had perfected his technique through playing thousands upon thousands of hours. Miles wasn’t one to woodshed as much as Bill Evans, for example, or as John Coltrane. John Coltrane was an insane incessant practicer, but miles treasured spontaneity above all things.

Brett McKay: Okay. So another artist that played on Kind of Blue was the pianist Bill Evans. Another one of my favorite musicians. I got his album Portrait and Jazz, I love listening to it. What was his background as a musician?

James Kaplan: Bill Evans was a glasses wearing white guy from New Jersey who could have been and maybe should have been in some ways, a great classical pianist. He studied classical piano, he loved classical piano. He had amazing technique, but something else happened when he was a teenager. He fell head over heels in love with jazz. And this is in the 1940s, Bill Evans is hearing all these great new sounds and jazz, falls in love with them. He goes to college to study classical music, but at the same time, he has also… Even before he goes to college, he has turned himself into the fastest boogie Woogie player in New Jersey. He keeps up this romance with jazz. He keeps playing jazz even as he’s studying classical music in college. And finally, when he is in his mid 20s decides to go to New York and he’s gonna make it in jazz, or he is gonna die trying.

If he doesn’t make it, he’s just gonna have to go home. He plays a lot of dances and weddings, bar mitzvahs, the way all jazz musicians have to do to make a dime when they’re coming up. And one night, Bill Evans had a gig at the Village Vanguard great jazz club in Greenwich Village. There was a famous group at the time called the Modern Jazz Quartet, who were playing the vanguard. And Bill Evans was the in-between player. When the modern jazz quartet were taking a break, Bill Evans would play piano in between. When the modern jazz quartet were playing the whole club would go dead silent. Reverend listening to Modern Jazz Quartet, when Bill Evans would start playing in between, everybody started eating and drinking and clinking glasses and plates. Anyway, one night, bill Evans is playing his in-between piano, and he looks down at the end of the grand piano, and there is the penetrating gaze of Miles Davis staring at him. Miles is looking at Evans. He’s listening, he’s taking it in. He’s hearing things he had never heard before in jazz piano. And a few months later, Miles hires Evans.

Brett McKay: What did Davis see in Evans? What was Evans doing that caught his attention?

James Kaplan: Evans, despite the fact that he looked like this nerd from New Jersey was bringing harmonies and textures out of modern Western Classical out of Stravinsky, out of Shostakovich, out of Rachmaninoff, that nobody had brought to jazz before. Miles had genius ears. And he was hearing in Evans a kind of jazz piano that Miles felt that was brand new and Miles really wanted to bring into his group.

Brett McKay: Evans talked about how he really wanted to bring feeling into his piano. He wanted you to feel something when he played and the way he played he just kind of like hunch over his head down. You could tell he was really trying to bring in the emotion to the piano.

James Kaplan: Yes. Evans deeply felt all that he played. He deeply loved the Western classical that had informed his jazz playing. And he couldn’t perform unless he was in a kind of emotional reverie. Unfortunately, the thing that happened as soon as Evans joined Miles Band, there was a huge backlash suddenly in the biggest small jazz group in the United States, in the most successful small jazz group in the United States. There was a white guy among black players, and among black audiences, and among black jazz musicians, a great backlash against Evans. It was psychically extremely damaging to Evans. He was a highly sensitive guy. Miles reassured him, but at the same time, miles had a way of continuing to haze Bill Evans Miles. Miles had a sense of humor. Somebody once asked Miles what his hobby was, and Miles said, making fun of white people on TV.

Miles liked to make fun of Evans too. Sometimes when Evans would hazard a musical opinion, Miles would say, “We don’t want no white opinions here.” But Miles also deeply respected Evans as a musician, and Miles used to say he didn’t care what color his musicians were. And so Evans had these conflicting forces working. He was accepted by Miles, unbelievably, by the great Miles Davis and Evans set about as soon as he joined Miles’ss Band. Evan’s set about turning himself into the biggest junkie in Miles’ss Band. And even though Miles wasn’t using heroin anymore, some of his other musicians were, and Evans joined them and then surpassed them as a heroin user. And this had unfortunately a huge effect on Evans’ music, on his life, on his career. And it shortened his life. He died at age 51 in 1980.

Brett McKay: So was Evans using heroin as a way to, I don’t know, kind of be accepted? Was that maybe he was thinking?

James Kaplan: Yeah. I mean, it was sort of a corollary of the Bird rule, right? To play like Bird you have to do like bird. It was this ridiculously conformist idea that Evans picked up on. If you’re gonna be a hip jazz musician, you gotta do heroine. And it was insane. It was crazy, but it got him a kind of acceptance among musicians that he had never had when he was the nerd wearing glasses from New Jersey.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that maybe it’s a lesson even amongst groups who consider themselves iconoclast or non-conformist. There still is gonna be a sense of conformity that you have to be aware of, or it’s another musician that played on Kind of Blue was John Coltrane. We’ve been talking about him a little bit throughout this conversation. What made him such an amazing saxophone player?

James Kaplan: Well, again, it’s that bolt of lightning. It’s the same thing with Sinatra walking around Hoboken at age 12 and hearing the music of the Spheres. There’s young John Coltrane growing up in North Carolina, and then Philadelphia walking around and sensing some kind of genius in himself that he was too shy. He was a deeply shy, deeply reserved, very, very modest human being. So he was conflicted. He was conflicted. He had a terribly sad childhood, boyhood and early and young manhood. He lost his father when he was very young, which was terribly painful to him and some other important male relatives. And so he became sad. He became withdrawn. He went within himself. He knew he had this musical talent, and he wasn’t sure exactly what to do with it. The thing he mainly did was practiced and practiced and practiced. He would play his saxophone. Everybody said, everybody who knew him as a kid, as a teenager, as a young man would talk about, they would hear him practicing behind closed doors at all hours. And if anybody complained, Coltrane would sit on his bed and practiced the fingering of his saxophone. So an insane over practicer. But he was also so modest that he began to play in bands that were beneath him, really, playing R&B, walking the bar. And he didn’t really come out of himself, emerges as himself until he was recognized, until he was seen and heard by Miles Davis.

Brett McKay: And Coltrane, he made a lot of innovations to jazz.

James Kaplan: As soon as Coltrane was able to rid himself of the need to imitate Charlie Parker, and there was a whole generation, dozens upon dozens of saxophonists who needed to rid themselves of the towering, mountain-like influence of Charlie Parker. As soon as Coltrane was able to find his own voice, he found a way of playing saxophone again, as Miles said, louder and faster than anybody else, and then beginning to explore chords, beginning to explore music in a way nobody had, even Charlie Parker had never explored before, playing tunes in a way that didn’t necessarily go with the way people had heard these songs before. When you listen to Charlie Parker play, when you listen to a great saxophonist like Dexter Gordon play, they were so wonderful, so beautiful, Sonny Rollins too. They would often quote from popular songs of the day or other jazz songs. One thing I say about Coltrane was that Coltrane only quoted from God. He heard things and played things nobody had played before.

Brett McKay: All right. So in 1959, all these guys synced up along with Cannonball Adderley to…

James Kaplan: And Cannonball, I just wanna interject. So, on Kind of Blue, you had not just these three geniuses; Miles and Train and Evans, but you had three other great players. You had Cannonball Adderley, and you had Paul Chambers, great bassist who died tragically young, I think 36 years old, again, heroin. You had Jimmy Cobb, great drummer. Cannonball Adderley was a terrific musician, terrific alto saxophone player who was soulful in a way that Coltrane was the great experimenter, and Cannonball was the great soul player. And Cannonball was itching to go out on his own and lead his own band, and very soon after Kind of Blue would do exactly that. You may remember the terrific jazz standard, Mercy, Mercy, Mercy, that was Cannonball’s song. And that’s a clue of what Cannonball brought to the music. But six great musicians on the album.

Brett McKay: So they all came together and they produced Kind of Blue. It’s considered a day to be modal jazz, the way they describe it. How would you describe modal jazz and what Kind of Blue is?

James Kaplan: Well, again, I don’t want anybody to snooze on us. Don’t want anybody to go to sleep. Modal jazz sounds mathematical, it sounds academic, it sounds, I don’t know. What Miles wanted to do was something nobody had done in jazz before. Jazz, from the time of its formation at the turn of the 19th into the 20th century, all the way up to 1959, jazz had been full of chords. It had been blues chords or it had been based on songs of the American songbook, standard tunes, T for two and stuff like that. And what you had was music that was based on a lot of chords. And it was beautiful, but Miles was restless. He was a restless artist, he was restless his whole life. He was always throwing off styles, he was throwing off friends, he was throwing off lovers, always changing. And Miles wanted to create something brand new and very, very simple. And so he wanted to throw out all these chords and he had gone to a performance of Les Ballets Africains, African Ballet, where they were playing all these African instruments, and he was enchanted by it.

And he was enchanted by the music too, a lot of which was kalimba, African finger piano. And so it was a whole different style of music, a whole different sound of music, and it wasn’t based on chords, it was based on just a couple of chords. And so Miles had this idea of creating an album that would be more about just a chord or two, sometimes just one chord for bar upon bar of the music with people improvising over that single chord, or maybe just two chords, as in the great linchpin of Kind of Blue, the greatest, arguably one of the greatest jazz tunes ever recorded, so What. So What is just two chords, listen to it. One chord, then another chord, and you have these amazing improvisations, including Miles’ss, over just these two chords. Miles wanted something that was quieter and simpler.

Brett McKay: Yeah. In the back of Kind of Blue, the jacket, Bill Evans wrote this thing called Improvisation in Jazz, and he talks about the making of Kind of Blue, and he said that basically Miles David had this basic framework that he wanted to have, but he conceived of these settings only hours before the recording dates, in a ride with sketches which indicated to the group what was to be played. And then he says, Bill Evans says, therefore you will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances.

James Kaplan: And an amazing thing about Kind of Blue, and it’s hard to wrap your head around, but every full take on Kind of Blue was a first take. And I’m gonna say that again, every full take on the album was a first take. So totally spontaneous. And yeah, built on these tiny little sketches. Miles would bring in a piece of paper, not even staff paper, not even music paper, but just a piece of regular white paper with a few notes drawn on it, and show it to the guys. And these, again, Miles was somebody who really needed anybody who played with him to be able to instantly get it, and to improvise beautifully right on the bandstand. And somehow, Bill Evans later said, every musician has recorded dozens of times. You never know, you go into a recording studio on a Wednesday morning, and you never know what’s gonna come out of it. Something good, something bad, something great, maybe. Nobody knew walking into these two sessions for Kind of Blue that greatness would result. Somehow or other, lightning struck, and these six guys all came together, all got in this incredible groove together, and played these historic first takes.

Brett McKay: Is that why you think Kind of Blue has endured? Like, I never get tired of listening to this thing, and I think it’s because it’s all first takes. Like, when you listen to it, you think, like you just feel like I’m listening to something that’s never happened before, and never happened since.

James Kaplan: Never happened before and never happened again. It’s really hard to say, Brett. There’s something very mysterious about it. Going back to Sinatra for a second again, you listen to Sinatra, I listen to Sinatra, as annoyed with him as I can get sometimes, for all kinds of reasons. The guy always gives me goosebumps. What is it that’s giving me goosebumps about Sinatra? What is it about Kind of Blue that gives you goosebumps? There’s a mystery to it. There’s a mystery to this album. There’s something about this album that you can’t, there’s a quiet, what I call it, I call a quiet majesty to Kind of Blue that you can’t put your finger on. It’s really hard to define, but it’s the best-selling jazz album of all time and arguably the best-loved. Why is that? There’s just this quiet to it and this mystery that just puts you in a different place. It takes you to a different place.

Brett McKay: And what I love about Kind of Blue, you have to listen to the whole thing. It’s not one of those things where you can just listen to songs, but you could, but to get the full effect of it, you have to listen to the thing in its entirety.

James Kaplan: Yeah. And you have to and you want to.

Brett McKay: Yeah, yeah. So they make this singular album. What happened to these guys after they made Kind of Blue?

James Kaplan: The three guys of my book all wanted to go out in different directions. Miles had already, of course, led many of his own groups and would continue to do so. Coltrane, Coltrane very much wanted to become a leader and very quickly became one. One month after finishing Kind of Blue, Coltrane recorded the great transformational album Giant Steps with that amazing number on it, Giant Steps, and very soon thereafter would make A Love Supreme and other great albums and become this pivotal, iconic, it’s an overused word, but there’s nobody like Coltrane. Coltrane wanted to be Coltrane. He loved playing with Miles, but he wanted to be Coltrane. He had to be. And Evans had to be Evans. Evans went out. He wanted to play trios, piano trios. He did that for the rest of his short career. Some would argue that Evans didn’t go as far musically, artistically, as Miles or Coltrane did. Some have argued otherwise. One of the great musicians I interviewed for my book was Jon Batiste. And Jon Batiste talked about an amazing album that Evans recorded called Conversations with Myself. What did Evans do? He double tracked.

He played piano and then on another track, he played along with himself playing piano. And Jon Batiste argued, that’s a real innovation. So Evans didn’t play music. He never played music that was difficult to understand. He felt deeply, he played beautifully lyrical music for the rest of his career. But it was a lyrical music, unlike piano music that other people were playing. So they all needed to go in their own directions.

Brett McKay: And did Miles Davis continue to try to push the envelope with jazz?

James Kaplan: Constantly. That’s all he ever did was push the envelope. But the thing about Miles was that Miles loved to sell records. Miles loved money. He loved living the good life. He loved having Ferraris and he loved fine wine, beautiful women, great art. He loved having his own big apartment on the Upper West Side. He loved all the things that money could buy. And so he had to sell a lot of records to do that. So he was always looking out for commercial opportunity. And when rock and roll music upset jazz’s apple cart and then some, it really dropped an atomic bomb into jazz in the early 1960s. Night of February 9th, 1964, the Beatles play Ed Sullivan, and that was the end of jazz, really, in many ways. Really, jazz started dying that night. Miles had to find a way forward. And so one of the ways he found forward was something that came to be known as fusion. It was a combination, a blending of jazz and rock and roll, electric instruments, electronic instruments, electric guitar, electric piano, electric organ. And a lot of people hated it. A lot of jazz purists hated it. But Miles recorded Bitches Brew, which was another huge success for Columbia Records and for Miles Davis. Miles found a way forward commercially, which wasn’t always popular with the gate guardians of jazz.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I’ve heard fusion jazz was jazz’s last ditch effort to make jazz popular again.

James Kaplan: Well, that’s one way of putting it, but I would say that a lot of it holds up. You listen to Bitches Brew today and it’s a powerful album. You listen to that beautiful, beautiful album, Filles de Kilimanjaro of Miles Davis, with a lot of electronic instrumentation on it. And that is gloriously lyrical music with a lot of electric and electronic instruments on it that holds up. So some of it holds up. And jazz just it changed. It transmogrified throughout the 1960s. Unfortunately for jazz, a lot of what happened in American culture impacted jazz. It was not only rock and roll music that beat jazz down, but it was the fragmentation of American culture. In the 1950s, Miles Davis was an American superstar. You could go up to a student on a Midwestern college campus and say Miles Davis, and they would know who you were talking about. And they would like jazz and they would think jazz was hip and jazz was the music of the future. What happened in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s, and then when the internet came in was the fractionalization of American culture, we became a nation of 10,000 tribes.

And so jazz continues to exist, but today it’s niche music, like so many other kinds of music, and it has its passionate adherents and it has its geniuses. There are great jazz players today and singers today. People like Robert Glasper and people like, Jazzmeia Horn, Esperanza Spalding, Aaron Deal, Brad Mehldau, all these wonderful, wonderful vocalists, instrumentalists, but jazz is, you know, in 1957, everybody in the United States would know who Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Miles Davis were, how many people today know who, I’m not going to name any musicians, I just named because I just named them, but they’re wonderful musicians. They’re great musicians, but they are known to the comparatively few who love jazz these days.

Brett McKay: Are these musicians today who are playing, are they innovating like Miles Davis did, or have we reached the edges of innovation in jazz? And now it’s just, we’re perfecting it. It’s kind of like classical music. Like there’s not really much innovation going on. We’re just perfecting what’s there.

James Kaplan: Yeah. I don’t think it’s ever possible within your time to know exactly where you are. I think it’s really only possible years and decades afterwards to know where the music is going. And so as an example, where Coltrane went after Giant Steps and after Love Supreme, he began playing up and down these chords into reaches of chords that nobody had heard before. And people, even jazz aficionados who had loved Coltrane’s music began to get very impatient with him and feel this music is too difficult to listen to anymore. And then people like Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor came in playing what was then called free jazz. And this was jazz that didn’t even have any chord structure. There were no melodies anymore. It sounded to so many people just like a lot of noise. It was one of the things that drove a lot of people away from jazz. But in retrospect, a lot of people think it’s great music. Is anybody doing anything like that today? I would say that you have people doing things today that may fall with difficulty on some years. But I think it’s going to take a long time before we know, before it all gets sorted out.

Brett McKay: Well, James, it’s been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

James Kaplan: Ah, well, they can go to my website, jameskaplan.net. They can go to Penguin Press’s website. And they can go to your terrific podcast. This terrific conversation we had right here, Brett.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, James Kaplan, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

James Kaplan: My pleasure, too.

Brett McKay: My guest today is James Kaplan. He’s the author of the book ‘3 Shades of Blue.’ It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find more information about his work at his website, jameskaplan.net. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/blue, where you find links to resources where we delve deeper in this topic and make sure you give ‘Kind of Blue’ a listen. It’s a great album. It’s available in full on Spotify. Check it out. Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archives, and while you’re there, sign up for our newsletter. We’ve got a daily option and a weekly option. They’re both free. It’s the best way to stay on top of what’s going on at AOM. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcast or Spotify, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to the AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.

Tags: 186, 974