I’m in my office holding a boombox with the wrapper of a Maxell cassette tape at my feet. I’m doing something I haven’t done in 30 years: recording the radio. Specifically, the static from an AM radio channel.

Why am I doing this?

I’m trying to record the voices of the dead, of course.

And I have media theorist John Durham Peters to thank for this Halloween-themed experiment.

The Historical Connection Between Technology and Spirits

Last month, I read Peters’ Speaking Into the Air, which explores the history of the idea of communication. I featured it in a recent Odds and Ends. It’s one of the most fascinating books I’ve read in a long time.

Peters has a section in Speaking Into the Air that traces the history of and the connection between technology and spiritualism — a social movement that arose in the 19th century and centered on the belief that the spirits of the dead could communicate with the living.

Victorians in England and the U.S. were so obsessed with death, that historians have called their fascination “a cult of death.” They held elaborate funerals, created mourning clothing and jewelry (including some made from the hair of the departed), and took post-mortem photographs of their deceased loved ones. And they tried to make contact with the Other Side by attending seances.

What created the Victorian cult of death?

Historians chalk it up to a few factors. High mortality rates, especially among children, made acute grief common, a cultural current that was only intensified by the high death toll during the American Civil War. (Though spiritualism ebbed in the late 19th century, it experienced a revival in the 1920s in the wake of the losses of WWI.) Most Americans had a deceased loved one they keenly yearned to connect with again. There were also changing religious beliefs about the afterlife that focused on reuniting with family and friends rather than heaven or hell. Another big influence on the era was the 40-year-long mourning period Queen Victoria, aka “The Widow of Windsor,” engaged in for her dead husband, Prince Albert. That lady made grieving a fine art and basically birthed the modern funeral industry.

Into this time of heightened preoccupation with death entered new technologies like the telegraph and telephone. The inventions seemed almost supernatural, separating spirit from body and transferring thoughts through the electrical ether. Along with the emergence of these new devices, a question materialized: if the living could communicate this way, why couldn’t the spirits of the dead be similarly reached?

Peters notes that it’s unsurprising that the Fox sisters, famous 19th-century mediums, claimed to communicate with the dead using telegraphic-esque raps in 1848, four years after the telegraph was invented. “That the telegraph opened access to the spirit world is not a fanciful metaphor,” Peters writes. “Spiritualism, the art of communication with the dead, explicitly modeled itself on the telegraph’s ability to receive remote messages.”

Edison’s 1877 phonograph invention added another tool to the spiritualist’s arsenal. Like the telegram and telephone, it seemingly separated spirit and body. You could capture a person’s voice on a record and then experience part of their essence without them being physically present. Maybe with the right technology, the thinking followed, people could record the voices of the dead.

Edison believed it was a real possibility. In 1920, he announced that he was working on a “spirit phone” that could communicate with and record the deceased. Though he never completed it, others pursued similar projects.

In his book, Peters mentions a 1995 Popular Electronics article about a 1950s documentarian who claimed to record ghost voices. Intrigued, I tracked down the article and discovered another fascinating rabbit hole of people using technology to interact with the Great Beyond.

The Birth of Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP)

In the late 1950s, Swedish film producer and painter Friedrich Jürgenson discovered something unexpected after recording bird songs in his garden. When he played back the tape, he heard human voices, even though he had been in the garden alone.

Psychologist Konstantin Raudive expanded on Jürgenson’s work, conducting over 100,000 recordings and publishing his findings in the 1971 book Breakthrough. Raudive claimed these mysterious voices spoke in multiple languages, often toggling between them within a single phrase.

This phenomenon became known as Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP) and sparked a movement of paranormal investigators who believed they could capture spirit voices using various recording devices. The scientific community remained skeptical, attributing the sounds to radio interference or audio pareidolia — a phenomenon where people’s pattern-seeking minds perceive familiar sounds, like voices, in random or ambiguous noise.

EVP has a passionate group of devotees today that swap tips on how to better record voices from the Other Side. You can find lots of YouTube videos of amateur EVP scientists recording ghost voices. They’re fun and interesting to watch.

My Journey Into EVP Research

Besides delving into the history of EVP, the Popular Electronics article provided instructions for conducting your own EVP recording.

I thought I’d try it.

First, an admission: ghosts freak me out.

I’m a believer in the afterlife and the idea that spirits may be amongst us, but I have no interest in interacting with the dead. Never done an Ouija board and never will. Too much bad juju for me. I’ll also never take part in a seance.

But recording the dead?

That doesn’t freak me out since I’m not interacting with ghosts. It’s more like lurking. I’m okay with lurking on ghosts.

The Popular Electronics article suggests asking the potential dead people who are hanging out in the room with you questions to get them talking. Since Jürgenson didn’t do that when he captured ghost voices, I figured I didn’t need to either. I’d happily stick to just creeping on the ghosts.

EVP Experiment #1: Microphone Method

The Popular Electronics piece suggested using a microphone to record ambient sound.

Since the article was from 1995, it recommended using a cassette recorder. I wondered if ghost voices can only be captured on analog. So I bought a Jensen Cassette Player/Recorder with a microphone.

I popped in a cassette, hit record, and let it run for a few minutes in my office in complete silence.

Results

The article said to look for “wispy voices that are difficult to understand” during the playback.

I played my recording back several times but didn’t hear anything except static.

No ghosts.

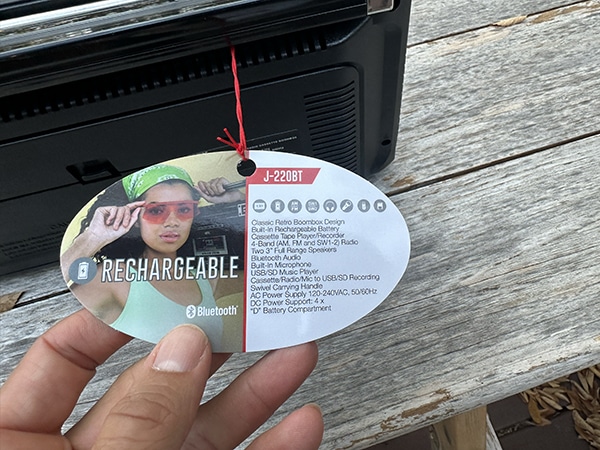

Experiment #2: Radio Method

Another method the article recommended to capture EVP was recording radio static from an AM station. “The quality of voices received using this method are certainly much better than that of the ones recorded by microphone,” the author assured. This was promising.

To record the radio, I bought this radical boombox. Just look at that thing.

In Ferris Bueller’s words, it is so choice.

And this bodacious babe with her bitchin’ shades was a good omen I’d capture poltergeist voices this time.

The article recommends tuning your radio to a part of the band with white noise. Once you find a channel playing static, you hit record on the cassette player.

I let the cassette record AM radio static for several minutes.

Results

I played the radio white noise back several times, but didn’t hear anything resembling a voice.

No ghosts.

The upside is that listening to the radio static over and over again really calmed my tinnitus for a good 20 minutes. I’m now also ready to have hip-hop dance-offs with my homies while wearing a midriff-exposing tank top.

Life starts at 40, my friends!

Experiment #3: Ghost Hunting Kit With Digital Recorder and LED Cat Toys

Maybe 21st-century ghosts can only be recorded using 21st-century technology. So I searched “record ghost voices” on Amazon. The top result was a “ghost hunting kit” with a digital recorder and, for some unexplained reason, four LED “flashing cat balls.”

Well, it’s not completely unexplained. The Amazon product page has an image of cute kittens next to a macabre-looking cake with the text “Flashing cat balls. Better to attract the attention of kittens” superimposed.

Yet there’s no further explanation for why you need to attract kittens during your ghost hunt.

Do spirits love seeing kittens as much as we mortals do?

Do you need to sacrifice a kitten to summon the ghosts?

You’re never told.

Anyways, I bought this kit mainly for the digital recorder, but I’ll use the LED cat balls in case they help get the ghosts I’m trying to record yammering.

I went to my backyard for this one. I initiated all four strobing LED cat balls and hit record on my digital recorder.

Results

I got some recordings of soothing bird chirping, but no EVP.

No ghosts.

I also did not attract any kittens. This ghost-hunting kit is getting a one-star Amazon review. Temu-level quality!

What This Experiment Taught Me About Communication With the Dead

So I wasn’t able to record EVP.

Maybe it’s because:

- Ghosts don’t exist.

- Ghosts exist, but none are in or near my house. It was built in 1987, and I don’t think anyone has died here.

- Ghosts are at my house, but they just weren’t in a chatty mood when I was recording.

- I needed to sacrifice a kitten to summon a ghost, but I didn’t do that because I’m no Satanic weirdo and what kind of monster would kill a kitten? Damn!

While I failed to contact the deceased, the experiment allowed me to tangibly reflect on Peters’ ideas in Speaking Into the Air, particularly this line: “Every new medium is a machine for the production of ghosts.”

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the telegraph and phonograph created ghosts. We’re still using technology in the 21st century to do the same. We read texts and emails from our dead loved ones. The social media profiles of those who have died are sometimes kept active, and people leave messages on them as though the deceased were still living and keeping up with their feeds. Thanks to LLMs, it’s now possible to train a chatbot on all the digital content a loved one left behind, which will allow you to simulate a conversation with that AI ghost in the machine. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Conclusion

While my EVP recording attempt didn’t yield supernatural results, it did provide a morning of entertainment and insights into the human desire to connect.

The main conclusion of Speaking Into the Air is that for all of human history, we humans have desired to have spirit-to-spirit communication with others. We really want to feel like someone completely understands us — that our mind becomes their mind. It’s a desire to transcend the limits of embodiment, a desire for the transcendent itself. Peters doubts such full and complete communication is possible, which is why so many of us feel alienated and lonely, even when surrounded by others.

Maybe one lesson from my failed attempt to record ghost voices is that what makes us human isn’t our ability to successfully communicate, but our persistent hope that real communication might be possible. It’s a hope that may never be fulfilled, but our strivings toward it are what make life so interesting, and . . . electric.