Modern culture is in the throes of a real love affair with travel. It’s become a central element of our zeitgeist, a main tenet in living a fulfilled, non-pedestrian life. Everywhere you turn, and no matter the dilemma, travel is offered as the cure.

Don’t know what you want to do after graduating college? Take a year off to travel.

Spark gone out of your relationship? Take more trips with your significant other.

Feeling restless and generally bored with life? Set off on an epic adventure around the globe.

Travel isn’t just framed as a cure-all for what ails us, either, but as a goal around which to build the other elements of one’s life. Don’t have children, the thinking goes, because they’ll hinder your ability to travel. Work for yourself and create passive income, so you can jaunt off to exotic locales whenever you want.

In a relatively safe and prosperous time, in a society that lacks many built-in challenges and hardships, travel has become the way to have an adventure, to demonstrate a kind of bravery — a cosmopolitan courage where one ventures into unfamiliar territory and undergoes a rite of passage to become an enlightened global citizen.

Travel is thus seen as both a tool of personal development and an almost altruistic moral good.

In short, as the old religious sources of guidance and identity have fallen away, a kind of “cult of travel” has developed in their place.

But is our faith in travel justified? Or have we forced it to bear the weight of far heavier expectations than it should be made to carry?

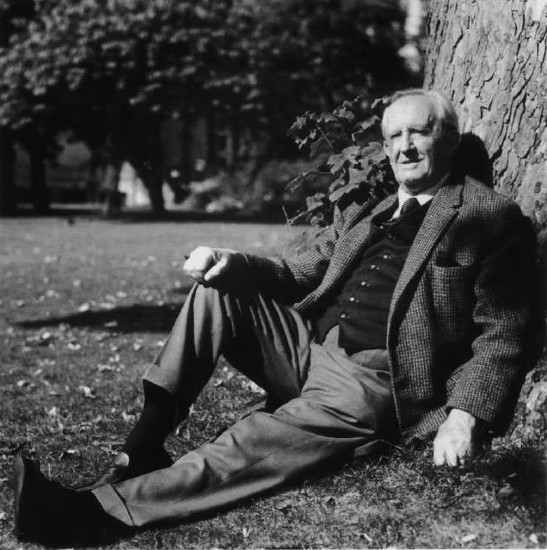

In an Oxford Suburb, There Lived a Creator of Hobbits

If travel has developed into a kind of cult, one of its sacred texts is surely The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien. The plot has been cited by many (including ourselves!) as a parallel to the way moderns should strive to escape the orbit of a boring, conventional life and get out and see the world: Bilbo lives a safe, comfortable, bourgeoisie existence, snug in his wood-paneled, fireplace-heated, well-stocked hobbit hole, until he is fairly dragged along on an adventure by a bunch of dwarves. He experiences a call to greatness he never knew he possessed, demonstrates courage and leadership, grows his perspective, and eventually returns to his suburban shire a changed hobbit. Here, it seems, is the story of the modern, domesticated, drone-turned-world-traveler, acted out in the realm of fantasy.

Seeing the book as inspiration to travel may work convincingly for many. But it didn’t move the behavior of one prominent exception: the author himself.

Tolkien’s own life was one of quiet, ordinary, unvarying domestic routine. He lived in a series of modest, very conventional suburban homes, and spent his days as professor, husband, and father. A typical day for Tolkien consisted of bicycling (he didn’t own a car for most of his life) with his children to early morning Mass, lecturing at Oxford’s Pembroke College, coming home for lunch, tutoring students, having an afternoon tea with his family, and puttering around the garden. In the evenings he’d do some writing, grade exams from other universities to earn extra money, or attend the Inklings, a kind of literary club. He rarely traveled, almost never went abroad, and when he did vacation, he took his family to thoroughly conventional, thoroughly touristy resorts along the English coast.

Between serving in WWI as a 20-something and the success of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in middle-age, nothing major or really exciting happened to Tolkien, and even after his books became international bestsellers, his lifestyle remained almost entirely the same.

“I am in fact a Hobbit,” he admitted, “in all but size”:

“I like gardens, trees, and unmechanized farmlands; I smoke a pipe, and like good plain food (unrefrigerated), but detest French cooking; I like, and even dare to wear in these dull days, ornamental waistcoats. I am fond of mushrooms (out of a field); have a very simple sense of humour (which even my appreciative critics find tiresome); I go to bed late and get up late (when possible). I do not travel much.”

The juxtaposition between Tolkien’s imaginative work and his domestic routine is encapsulated well in one of the short reports he sent his son in 1944 on the progress he was making writing The Lord of the Rings: “I managed to get an hour or two’s writing, and have brought Frodo nearly to the gates of Mordor. Afternoon lawn-mowing. Term begins next week, and proofs of Wales papers have come. Still I am going to continue ‘Ring’ in every salvable moment.”

So what do we make of the fact that a man who lived such a narrow, limited, conventional life, also produced works featuring epic, expansive adventures filled with characters who leave behind their ordinary creature comforts to embark on great, risky, challenging quests?

Was Tolkien a hypocrite? Were his books merely a form of wish-fulfillment, a chance to live out in fantasy the kinds of things he was too timid to enact in his own life?

Not if you understand what Tolkien was truly trying to do with his stories, and what he considered the most important kind of adventure.

The Hidden Dimensions of a Hobbit Hole

Part of what inspired Tolkien’s characterization of hobbits, besides his personal life, was the general character of his fellow countrymen. As he told one interviewer, “The Hobbits are just rustic English people, made small in size because it reflects the generally small reach of their imagination — not the small reach of their courage or latent power [emphasis mine].”

Tolkien never doubted that his neighbors had physical courage in spades — in the trenches of WWI, he had witnessed the steadfastness of enlisted soldiers firsthand. When asked to rise to the occasion, they did so splendidly and without reservation.

Tolkien in fact saw such courage as one of the defining characteristics of hobbits. When his son Christopher was flying planes for the Royal Air Force during the Second World War and anxiously faced deadly risk and fearsome enemies, he encouraged him to “Keep up your hobbitry in heart!”

No, the thing Tolkien thought the average hobbit, or Englishman, lacked was not bravery, but a thoroughly vitalized imagination — the desire to entertain new ideas and perspectives, to leave behind the status quo and take a journey of faith, personal growth, and moral challenge.

For Tolkien, nothing in this world — not its culture, knowledge, assumptions, and expectations, nor its rocks, trees, and people — was entirely as it seemed. Hidden behind what the poet P.B. Shelley called “the veil of familiarity” existed other layers and dimensions. While such realms cannot normally be seen with the eye, they are sensed through poignant pangs of longing for something more — the occasional, fleeting feeling of being on the threshold of something greater.

Not enough people, Tolkien felt, had the imagination to consider this idea seriously, nor the courage to follow their longing beyond the surface of things. The average bloke was like the Bagginses of The Hobbit, where you know what he “would say on any question without the bother of asking him.” Most folks don’t attempt to draw back the curtain on another realm of meaning — can’t be bothered to penetrate the conventional, comfortable, respectable notions of the way things are in order to discover deeper truths.

For Tolkien, those important truths included the idea that all of life — whether in suburbia or on an actual battlefield — constitutes an epic, heroic clash between good and evil, dark and light; that everyone’s choices, no matter how “little” of a person they are, matter; and that each individual’s small story is part of a larger, cosmic narrative. Everyone has a part to play and a pilgrimage to make — not necessarily a physical journey, but a moral and spiritual one.

Tolkien further believed that reading myths was one of the surest ways to begin such a journey. In myths one finds fantastical explanations of who we are, how we got here, and what we’re capable of. Such stories, Tolkien held, are filled with echoes of Truth with a capital T – “a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality” that was truer than anything strictly factual. A good myth, in departing from reality, paradoxically helps us rediscover it — reminding us that beneath the blandness and busyness of our day-to-day lives, lies heroic and mythic potential.

It’s for this reason Tolkien wished to develop his own mythology, and successfully did so in The Hobbit and his other works. Bilbo takes an adventure that runs much deeper than the external landscapes and enemies described on the page; his is a pilgrimage through an epic mythological world in which he battles the forces of darkness, discovers his destiny, and, as the author of Bilbo’s Journey puts it, undergoes, a “rite of passage from wisdom to ignorance and from bourgeois vice to heroic virtue.”

By vicariously and imaginatively following along on Bilbo’s quest, the reader ends up taking a there-and-back-again journey of his own. As Tolkien’s friend C.S. Lewis wrote in his review of The Hobbit, the story admits the reader to a world that “becomes indispensable to him…You cannot anticipate it before you go there, as you cannot forget it once you have gone.”

Both Lewis and Tolkien believed ardently in the power of “fairy stories” to, as the latter put it, offer “sensations we never had before, and enlarge our conception of the range of possible experience.” Lewis explained the effect of imaginative tales on the reader:

“Fairy land arouses a longing for he knows not what. It stirs and troubles him (to his life-long enrichment) with the dim sense of something beyond his reach and, far from dulling or emptying the actual world, gives it a new dimension of depth. He does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods: the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.”

In other words, books like The Hobbit are not necessarily supposed to inspire trips to far-flung lands, but rather to restore the freshness of familiar surroundings right in front of our faces. Once you discover this doorway to realms beyond, you’re able to see the world through a mythological lens, and find that there are hidden dimensions even within the walls of one’s hobbit hole. Once you’ve been there and back again, your perspective is forever changed; you begin to see things as they really are. Everything from the view outside your apartment to your commute to work can become more meaningful, even magical.

That Tolkien could step through this threshold whenever he desired, his otherwise bourgeoisie lifestyle notwithstanding, is what set him apart from other “hobbits.” And it is what accounts for his obliviousness to the allure of physical travel. As one of his biographers put it, “his imagination did not need to be stimulated by unfamiliar landscapes and cultures”; that he could simply sit down at his desk and immediately begin exploring the terrain of Middle-earth explains why he “did not altogether care very much where he was.” For Tolkien, his domestic routine, no matter how familiar, remained perennially fresh.

Tolkien’s immersion in his imagination did not represent an escape from reality, but a reacquaintance with it. He saw clearer than most the way in which even the most ordinary life is filed with epic quests, wrenching conflicts, and the heroic choice between courage and compassion, and greed and selfishness. So that despite the “narrow” scope of his life, one cannot help feeling it was far more expansive than those who fill their Instagram profiles with photos of their globe-trotting travels.

What Tolkien understood is that when it comes to life’s most important journeys — quests of spirituality, self-discovery, and self-mastery — location is irrelevant.

The greatest adventures don’t require a passport.

In fact, our outer journeys can inhibit our inner ones.

Many Who Wander, Are Indeed Lost

“For I measure distance inward and not outward. Within the compass of a man’s ribs there is space and scene enough for any biography.” –Henry David Thoreau

Certainly there is absolutely nothing wrong with travel when it’s given its proper weight and is stripped of undue moral significance, exaggerated powers, and inflated expectations.

The recalibration of those expectations begins with the acknowledgement that there is nothing inherently valuable about travel. The benefits associated with it, like the chance to expand one’s perspective, grow in maturity, and learn how to handle uncertainty, are certainly real, but do not automatically accrue simply by moving from point A to point B. If they did, the author of Eat, Pray, Love, who began her globe-trotting adventure flaky and narcissistic, would have ended her trip a better person, and yet — spoiler alert — she seems no less self-absorbed by the journey’s end.

The value that can be derived from travel only comes to those who engage it with the right mindset and a preexisting self-sufficiency — qualities that can be developed anywhere, and must be formed before you start out.

Many people hope that traveling will help them change or find themselves, but if you can’t become the person you want to be right where you are, then you won’t be able to do it when you’re 5,000 miles distant. Because, of course, wherever you go, you bring yourself along with you. As Ralph Waldo Emerson put it, folks who are unhappy with their lives, and look for fulfillment in exotic and ancient lands, merely carry “ruins to ruins”:

“It is for want of self-culture that the superstition of Travelling, whose idols are Italy, England, Egypt, retains its fascination for all educated Americans. They who made England, Italy, or Greece venerable in the imagination did so by sticking fast where they were, like an axis of the earth. In manly hours, we feel that duty is our place. The soul is no traveller; the wise man stays at home, and when his necessities, his duties, on any occasion call him from his house, or into foreign lands, he is at home still, and shall make men sensible by the expression of his countenance, that he goes the missionary of wisdom and virtue, and visits cities and men like a sovereign, and not like an interloper or a valet.

I have no churlish objection to the circumnavigation of the globe, for the purposes of art, of study, and benevolence, so that the man is first domesticated, or does not go abroad with the hope of finding somewhat greater than he knows. He who travels to be amused, or to get somewhat which he does not carry, travels away from himself, and grows old even in youth among old things. In Thebes, in Palmyra, his will and mind have become old and dilapidated as they. He carries ruins to ruins.

Travelling is a fool’s paradise. Our first journeys discover to us the indifference of places. At home I dream that at Naples, at Rome, I can be intoxicated with beauty, and lose my sadness. I pack my trunk, embrace my friends, embark on the sea, and at last wake up in Naples, and there beside me is the stern fact, the sad self, unrelenting, identical, that I fled from. I seek the Vatican, and the palaces. I affect to be intoxicated with sights and suggestions, but I am not intoxicated. My giant goes with me wherever I go.”

Or as the Stoic philosopher Seneca observed two-thousand years ago:

“[Travelers] make one journey after another and change spectacle for spectacle. As Lucretius says, ‘Thus each man flees himself.’ But to what end if he does not escape himself? He pursues and dogs himself as his own most tedious companion. And so we must realize that our difficulty is not the fault of the places but of ourselves.”

Those who travel in search of something they lack, find that whatever was holding them back from attaining it at home, is waiting for them at the airport when they land.

If one feels that they cannot find themselves or fulfillment without making a certain trip, then they may know for certain that they are setting out with the wrong mindset — the one that says, “If I just had/did X, everything would change.” It’s the same mindset that makes you feel that if you just found the right diet, you’d lose weight; if you just got the right organizing app, you’d get more done; if you just got a better paying job, you’d be happy. In such cases, you’re not actually looking for a tool to kick-start your goal, but a distraction from having to work on it at all.

If you can’t find satisfying adventure in exploring your own backyard, you won’t discover long-lasting satisfaction backpacking through Europe. If you can’t create a rich inner life in suburbia, you won’t develop one in the ashrams of India. If you can’t find freshness in the familiar, and fulfillment in the quests of self-mastery, spirituality, and virtue, then a summer’s trek around the globe won’t ultimately save you from a life of empty dullness.

Happiness, improvement, and fulfillment can be found in any circumstance, or not at all.

A Round, and Round, and Round Trip Ticket

Travel is often framed as an exercise in courage, and the endeavor of the perennially curious. And yet it can also be an excuse for the exact opposite. Needing the structure of a trip to find excitement and adventure shows a lack of imagination, rather than an abundance of it. And in cases where travel is used to flee the mess, disappointments, and deficiencies of one’s normal life, rather than facing them head on, nothing is more cowardly.

And counterfeit.

Travel offers the same feeling of being on the threshold of something strange and wonderful — of existing in an in-between liminal state — that Tolkien was so fond of seeking, but its effect is more temporary, and fails to point beyond itself to something greater. The traveler who embarks without a preexisting structure of self-knowledge and character, intending instead to find it along the way, is set up like a sieve; when the longings produced by his journey arise, they pass right through him. During the trip itself, he feels invigorated, purposeful, full of momentum, and on the path to bigger and better things.

But he has merely mistaken movement for progress.

Once he arrives back home, these feelings dry up, and can only be reinvigorated by undertaking another excursion, and getting another hit of the travel rush. The threshold experience, rather than being a doorway to greater things, merely turns into a cycle of its own duplication, an empty series of passport stamps.

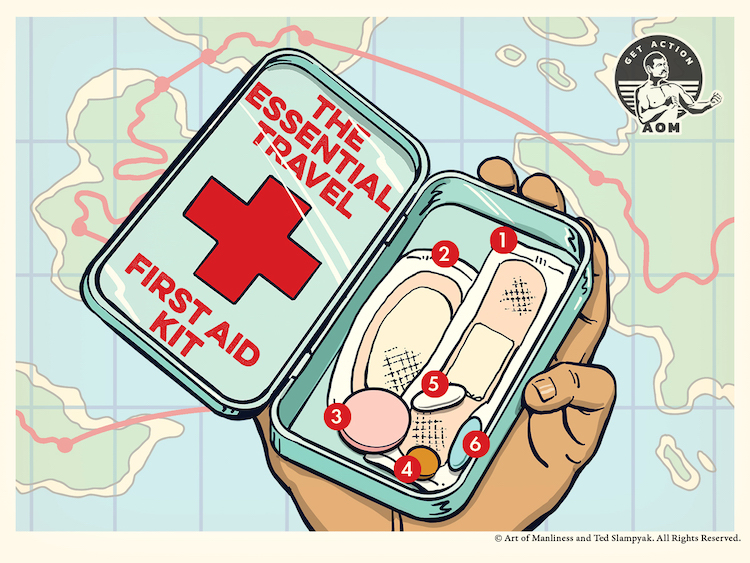

Travel then, should ideally be approached the way one does a healthy romantic relationship. Rather than looking for a partner who will fulfill all your desires, you arrive as a fully realized person yourself. Instead of looking for your lover to complete you, they simply expand and enhance the robust foundation of self you’ve already developed.

In the same way, travel should be seen not as a magic pill, a cure-all, something necessary to your personal development, but an optional enrichment for those already living purposeful, fulfilled lives — an engaging pastime, a hobby like any other, enjoyed by some, and not by all.

Travel should never be an escape from life; only an enhancement of it.

Conclusion

“Our limbs have room enough but it is our souls that rust in a corner. Let us migrate interiorly without intermission, and pitch our tent each day nearer the western horizon.” –Henry David Thoreau

How much one travels is presented these days as a kind of litmus test: the more you travel, the more courageous, cultured, and non-conventional your life is taken to be; the less you travel, the more your life is assumed to be boring, conventional, and narrow.

But the lines are not so easily drawn. A man who’s visited every continent may have a soul as shallow as a thumbnail scratch, while a man who’s never left his hometown may have a spirit deeper than an oceanic trench; the man whose Instragram profile is filled with images of ancient ruins and beachside sunsets may have an extremely limited view of life’s possibilities, while the man who lacks a single passport stamp has cultivated an expansive and far-reaching mind; the man who’s bravely ventured across the globe may be frightened stiff of facing himself and grappling with the ordinary, while the man who’s snug at home has bravely faced up to exactly who he is and what his life has amounted to.

And vice versa, of course.

Nor do these types have to be mutually exclusive.

But even if you wish to be a man whose travels are as rich as his inner life, start with the latter, rather than the former.

Seek depth first, then width.

And know that life’s greatest, most important adventures can be begun right where you’re sitting right now. Without even packing your bags, you can set off on a pilgrimage to greater self-discovery, epic excellence, and heroic virtue, so that, like Bilbo, you’ll soon be “doing and saying things altogether unexpected.”

__________________________________________

Sources:

J.R.R Tolkien: A Biography by Humphrey Carpenter

Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship by Colin Duriez

Bilbo’s Journey by Joseph Pearce

“How to Travel–Some Contrarian Advice” by Ryan Holiday