Puzzles may seem like fairly pedestrian pastimes — fun ways to while away a rainy afternoon. And while they certainly do make for satisfying diversions, my guest would say they’re also more than that, and can teach us plenty about life as well.

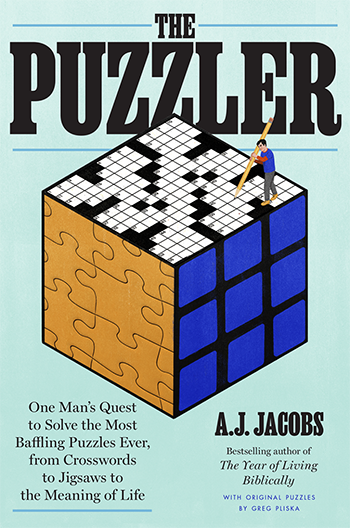

His name is A.J. Jacobs, and he’s the author of The Puzzler: One Man’s Quest to Solve the Most Baffling Puzzles Ever, from Crosswords to Jigsaws to the Meaning of Life. Today on the show, A.J. explains what makes a puzzle a puzzle, and why we’re drawn to them and enjoy them so much. We then discuss the charm of certain puzzles, from crosswords and Rubik’s Cubes, to jigsaws and mazes. Along the way, we discuss some of the strategies behind solving these puzzles, and how these strategies can help you become an all-around better thinker and decision maker, and better at navigating the puzzling dilemmas of life itself.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- A.J.’s previous appearance on the podcast — Episode #53: Experimenting With Your Life

- Maki Kaji — the father of Sudoku

- AoM Article: The Best Riddles for Kids

- A.J.’s wife’s scavenger hunt company, Watson Adventures

- Wordplay

- The Great Vermont Corn Maze

- Tanya Khovanova’s Math Blog

- Kryptos — art sculpture with encrypted code on the grounds of the CIA

- Apophenia

- Sunday Firesides: Take It Bird by Bird

Connect With A.J. Jacobs

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Puzzles may seem like fairly pedestrian pass times, fun ways to while away a rainy afternoon. While they certainly do make for satisfying diversions, my guest would say they’re also more than that. He they could teach us plenty about life as well. His name is AJ Jacobs, and he’s the author of The puzzler: One man’s quest to solve the most baffling puzzles ever, from crosswords to jigsaws, to the meaning of life. Today in the show, AJ explains what makes a puzzle a puzzle and why we’re drawn to them and enjoy them so much. We then discuss the charm of certain puzzles from crosswords and rubik’s cubes to jigsaws and mazes. Along the way, we discuss some of the strategies behind solving these puzzles and how these strategies can help you become an all round better thinker and decision-maker, and better at navigating the puzzling dilemmas of life itself. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at awin.is/puzzles. AJ Jacobs, welcome back to the show.

AJ Jacobs: I am delighted to be back and Brett it’s been since episode 53.

Brett McKay: Man, yeah, you were on one of the first ones. You were among the first you know.

AJ Jacobs: I was honored to be, yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and now we’re in…

AJ Jacobs: And now look at you.

Brett McKay: No, yeah, now we’re in the 800s and you got a new book out called The puzzler: One man’s quest to solve the most baffling puzzles ever from crosswords to jigsaws, to the meaning of life. And again, this book is you take this sort of George Plimpton-esque adventure, sort of immersion journalism, and this time you explore puzzles. What led you down on that path?

AJ Jacobs: Well, I’ve always loved puzzles since I was a kid, I used to do crosswords. I would make these pencil mazes and that took up my whole living room floor, and I think it informed my world view. I think I saw all of life as a puzzle. So some of my previous books, I actually can sort of reframe as puzzles. I wrote a book on The Year of Living Biblically, and that was about the puzzle of religion and what do I teach my kids? So I’d always loved them, and I like to have a nice strong starting story for my books, and a few years ago, I had this crazy experience that provided me one, which was that I was the answer to one down in the New York Times crossword puzzle. It was author AJ blank, and I was the answer, AJ Jacobs. And I thought as a word nerd, this is the greatest moment in my life. Yeah, this is the Holy Grail. My wedding was pretty good, but this, this is great. And then my brother-in-law emailed me and he did congratulate me. He did say, “Congrats.” But he also pointed out I was in the Saturday New York Times puzzle.

And as you may know, that is the hardest puzzle of the week, harder than Sunday, all the answers are totally obscure. So his point was, “This is not a compliment. This is actually proof that no one knows who you are. This is proof in black and white of your obscurity.” So then I was kind of bombing out, the roller coaster had hit the navier, and then I went on a podcast and I told that story, and it happened that one of the New York Times crossword makers was listening, and he decided to save me and put me in a Tuesday puzzle which is one of the easier ones. It’s not Monday, but Tuesday is where Lady Gaga and Joe Biden… That’s where they appear. So he saved me from my obscurity and I’ll forever be grateful and I thought, “Well, this is fun.” And it had gotten me back into doing crosswords on a regular basis. I had become addicted and I thought, “Well, why do I love these so much? Why do millions of people spend millions of hours on puzzles of all kind?” So I thought, “Let me do a deep dive and just spend two years hanging out with the best puzzle makers and puzzle solvers, and going around the world when I could.” And that’s what I did, and that’s the… The book is the result of that.

Brett McKay: Okay, we’ll start off with a very basic question. What makes a puzzle a puzzle? Are there philosophers knocking this question around?

AJ Jacobs: I think so. It’s not as popular as the meaning of life, but it is… It all depends on your definition. And I have a very big tent for my definition of puzzles. So in the book I talk about 20 different kinds of puzzles, everything from visual puzzles like Where’s Waldo, to crosswords, to Japanese puzzle boxes, but I think what unites them all is that they all are a problem that requires a solution that involves ingenuity. You’ve got to have an unusual idea to solve them. I guess the cliche is out of the box. You’ve gotta think outside the box, and that cliche comes from a puzzle, so I feel okay using it. It was originally meant there’s a puzzle with nine dots in a square and you have to draw four lines to connect all the dots. The only way to do it is to go outside the box with your lines, so that to me is what a puzzles the definition and also the attraction, because I think… I personally love to think of creative ideas, and I think that’s what has propelled humans. That’s how we got the wheel and fire. That is the type of thinking that has brought us humanity’s greatest advances.

Brett McKay: Well, I like… A Japanese puzzle maker gave this really succinct definition of a puzzle and I really liked it and it uses just symbols. It’s question mark, arrow, exclamation point.

AJ Jacobs: Yeah. I love that. And it means the question mark is when you arrive and you’re baffled and, “What’s going on?” The arrow is the struggle, the trying things out, trying to figure, to solve the problem. And the exclamation point, is that aha moment, that Oh my God, that’s great. That is… And what’s interesting… Two things, first of all, I think that’s a good… Not just for puzzles, I think is a good summary of so much of stories, stories that require conflict and resolution, life perhaps.

Brett McKay: But I also love this guy, his name was Mackay Kanji, he’s the godfather of Sudoku. He popularized Sudoku. And he said The key to puzzles and the key to life is you have to enjoy that arrow, you can’t be all about the exclamation point, you have to enjoy the solving process and the journey. And I love that, and I try to remember that when I am in the middle of the most frustrating puzzle and you wanna throw it across the room. And I try to remind myself, this is the arrow. Just enjoy the arrow. It’s all part of the journey.

Well yeah, so that arrow part, puzzles can be really frustrating at times, and yet people spend hours on them, there’s something enjoyable about the frustration. What is it about puzzles? Why do we even do puzzles anyways.

AJ Jacobs: Well, I think it’s the same reason we do marathons and climb mountains, and I don’t know if you’ve had Paul Bloom on your podcast, but he’s a great psychologist, and he talks a lot about why do we enjoy painful things? And there are a couple of reasons. One is the cultural. We have the puritan work ethic, we are sort of accustomed to associating hard work with good things, but the second is that is wired into us as humans, we are wired to want to work hard to achieve our goals, and there’s the cliche, no pain no gain. I actually don’t think that’s technically true, you can have gain without pain, but a lot of times the pain does yield something good, so I prefer different people like different kinds of pain, so I am not someone who’s gonna climb Everest, but I am happy to tackle the hardest puzzles in the world.

Brett McKay: Also too… You talk about this throughout the book. Some of the people you talk about, that puzzles, you know there’s a solution to it, and a lot of life is just uncertain, and you don’t know what the right thing to do is for in a relationship, or should I take this job, puzzles, even though it might take you forever, you know there’s an answer and there’s something satisfying about that.

AJ Jacobs: Oh yeah, especially now that life is so confusing and there are no easy answers, this is the platonic ideal of a problem where there is always an answer, and I say to me, there are many parallels between life and puzzles. But life is more like a jigsaw puzzle where the pieces are always changing shape, and maybe the picture is also changing, so it’s more complicated. But puzzles are good training for it, nonetheless.

Brett McKay: Do we know how long humans have been doing puzzles, like what’s the earliest known puzzle?

AJ Jacobs: Again, it depends on how you define puzzle, there is… I talked to a scientist who studies slime molds, and they solve mazes, she’s studying how they put food at the end of a maze and a slime mold figures out how to get to the food. So there’s that type of puzzle, the earliest puzzles that I know of in terms of actual what we consider puzzles are probably riddles, riddles have been around for millennia, and in every culture, you can find them… The earliest riddle, I’ll tell it to you, it’s not a knee slapper, it’s not like the whole… You’re not gonna love it, but I guess it was funny back in ancient Babylon, it’s a Babylonian riddle, and it says What gets fat without eating, and pregnant without having sex. And the answer is, I won’t even make you guess ’cause it’s…

Brett McKay: I remember it. It’s clouds.

AJ Jacobs: Oh you do. Yeah, exactly. It’s a rain cloud.

Brett McKay: A rain cloud yeah.

AJ Jacobs: Nice work, remembering. So yeah, that was the first… And that has continued. Riddles continue to be a puzzle form that’s in every culture, and also there’s the crossover of history and puzzles. I talk in the book about a puzzle that helped save western civilization, which was… It was in 1942, and there was a really hard puzzle in the London Telegraph Newspaper, and at the end it said, If you have solved this crossword in less than 12 minutes, then contact this number, and that number happened to be the code-breaking arm of the British spy agency, it was the Bletchley Park, where they helped crack the Nazi Code and win the war. So puzzles can save the world. That’s my thesis.

Brett McKay: That’s great. So let’s talk about some of these puzzles you highlight, you start off with crossword puzzles, which is a good starting point because this whole thing kick-started with you being a an answer to a crossword puzzle clue. One thing I was surprised about crossword puzzles is it’s a relatively new type of puzzle. When was the first crossword puzzle published?

AJ Jacobs: The first one was in 1913 in the New York World newspaper. And what I love, my favorite part about that history is the New York Times looked down on crosswords, a lot of other newspapers started to print them and they became a big craze. There was a Broadway show about them, but in the 20s and 30s, if you look at The New York Times, they ran articles about how horrible crosswords were for society, it was like… They treated it like crack cocaine, they said it was a pestilence, they said that people were murdering each other and divorces were happening, that there were prison riots over crosswords, literally, these are all headlines in the Times. And then in 1942, World War II came and they decided, people needed a distraction and they finally embraced it, and now they’re considered the top of the puzzle pyramid.

Brett McKay: So what makes a good mix for a good crossword puzzle? Have they… The have crossword puzzle makers… They have this down to a science yet.

AJ Jacobs: I wouldn’t say it’s a science, it’s still an art and a science, but there are definitely parts that make it better, and to me, there are two parts of the crossword, there’s the trivia, so what’s the river in Uganda, and then there’s the word play, and that is what true crossword puzzle lovers usually prefer the word play. Will Shorts, who’s the editor of The New York Times crossword says, his favorite clue ever… It was something like, it turns into another story, and the answer was spiral staircase. So I am a fan of Word Play as well.

Brett McKay: So you do these crossword puzzles, you do the hard one, and along the way you find these insights about problem solving from crossword puzzles. What were the big ones that stood out to you that were applicable to other parts of your life?

AJ Jacobs: Well, a whole bunch. One is, some people do the crossword in pen. I do it in pencil and I am proud, because I think the eraser is one of the greatest inventions we have. Or the delete key. I do it online sometimes. So the key to me solving any problem is cognitive flexibility. You cannot fall in love with your hypothesis and say, This is the way it’s gotta be, whether in crosswords or in life. And I think that’s a huge problem that afflicts us as a society. We are so sure that our answer is the right one, we are unwilling to listen to evidence or to the other side.

So, eraser, the way of the eraser. That’s a big one. Another one I have is… And Bill Clinton actually talked about this in the crossword puzzle documentary, it’s called Wordplay. And he talked about, sometimes you look at a really hard crossword and nothing will click for five minutes. You’ll just be going through and nothing. And then finally, you get the… Get one answer, you get a little toehold, and from that you can work out and get another and another and another. So that is a way I solve a lot of problems, is I just find that one toehold, that one way in, and then you can expand out. Even writing the book or a chapter, I’ll find that one quote or vivid anecdote that I know will work, and then I will expand from there. So that was another lesson. And there are tons others. But, yeah, I find crosswords and puzzles are like… They’re like wise philosophy teachers. They teach you how to think and live.

Brett McKay: Yeah. The find the toehold… I mean, I think people naturally do that with a crossword puzzle. They just find a the clue they can answer right away, ’cause then it just… From there, it just gets the ball rolling. I’ve done that technique, like you in writing, when I have to write something and the… You try to write the beginning, it’s like, This is not coming, but I’ll just write the part that just… It’s really easy. And then the beginning writes itself, once you…

AJ Jacobs: Exactly.

Brett McKay: You get going.

AJ Jacobs: Oh yeah. That’s so huge. Right.

Brett McKay: And the other thing I noticed with crossword puzzles, when I did them, being patient, being able to put it aside, and then sort of marinating and letting it stew, and then you come back to it and you look at it again, it’s like, Oh yeah, this is what that is. It was so obvious. And I’ve applied that to my life as well.

AJ Jacobs: So important. I mean, first of all, I love the word marinate, ’cause I think that’s what your brain is kinda doing, marinating on the problem, not consciously, but somewhere back there. And there is… There’s lots of science on this that one of the best ways to solve problems is put it away, do something else for an hour, a day, a week, and then you come back and you’ll have a fresh perspective, and you’ll have been working on it. And what I love is this is not a new insight. Leonardo Da Vinci wrote a guide to how to be a painter, and one of his main suggestions is, if you get to a tricky part, a problem in your painting and can’t solve it, walk away and then come back, and you will be able to solve it.

Brett McKay: Well, another thing that I did… So I did crosswords puzzles a lot when I was in high school. This one summer I worked at the paint shop at the University of Oklahoma’s Medical School. And I was just with these salty… The were like 50, 60-year-old guys, just really gritty. But they love doing the crossword puzzle. I’d get there in the morning and there’d be some guy there with the paper folded, doing the crossword. And we’d work on it at lunch break and then our different breaks. But it was… It’s a very communal activity. We did it together. So you have these guys who were telling dirty jokes five minutes earlier and trying to figure out some word play, sophisticated word play.

AJ Jacobs: Well, I love that you bring that up because there is a stereotype that puzzles are a solo activity and let you just sit in the corner with your crosswords. But almost everyone in the puzzle community I ran into, it’s the complete opposite. It’s such a communal activity and you’re talking with your friends and comparing and saying, You have any hints for this, or, What do you think that is? And it really bonds people together. There’s even some social science that says, One of the… If you have people of different opinions, like liberals and conservatives, one of the best ways to bring them together is to have them solve a puzzle. And you can see that in team building… My wife actually owns a company, Watson Adventures, it’s wonderful, and they put on scavenger hunts and it’s all about people collaborating to solve these puzzles, because it works for the… Everyone has a strength. Someone might be really good at visual puzzles or at math puzzles or word puzzles. So I love that aspect.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. Okay, so we’ve talked about crossword puzzles. Another puzzle you highlight is the Rubik’s cube. It’s an interesting… This is a new puzzle too, but it became this cultural phenomenon. I can’t imagine a world without Rubik’s cube. So what’s the… Yeah, what’s the story there?

AJ Jacobs: Oh yeah. Now. Well, first of all, what’s your history with… Have you ever solved it?

Brett McKay: I solved it when I was like 10 by taking it apart and then putting it together. I had… There was actually… There’s that book that was written in the ’70s by that one kid. My parents actually had that. And I remember, I think I was like nine or 10, trying to follow the instructions in that book, and I was like, “No, I’m just gonna take it apart and put it together.” That’s the only time I solved the Rubik’s cube.

AJ Jacobs: Well, first of all, that is one interesting way to solve a puzzle, is… It’s sort of the Gordian knot. You chop it in half and say, Enough of this. I’m gonna… So kudos to you for solving it that way. It started in the ’80s, and it was huge. And then it kinda faded away. But then it came back because of YouTube. So now there are millions of kids who are obsessed with it, and they… There’s the speed cubing competitions, which will blow your mind. These kids… The world record for solving a Rubik’s cube is three and a half seconds. It’s crazy. I can’t even look at it in three and a half seconds, and I don’t know where to start. But anyway, I did… I, eventually, during this project, I solved the Rubik’s cube. It took me 50-plus years. I guess, 40-plus years.

But I learned a lot about Rubik’s and the allure of it and why people love it so much. And I think part of it is, is just an extraordinary fact that this little cube has, I don’t know if you remember, but the number is insane, 45 quintillion possible arrangements. It’s just a mind-boggling number. We can’t even comprehend that. That’s more than the stars that you can see. It is just insane. And yet, if you do it correctly, you can get that one arrangement that is the right solution. So to me, that’s… That is super inspiring. 45 quintillion. That’s like the smallest needle in the biggest haystack ever. You can actually solve something that has 45 quintillion options.

Brett McKay: Yeah. The 45 quintillion number really instills a lot of humility in you.

AJ Jacobs: Yeah, I agree.

Brett McKay: Thinking about it, how big it is. But I like how you use the Rubik’s Cube to explore the difference between creative problem-solving and skill. And there seems to be some tension there between the generations, like the original Rubik’s cube solvers and today’s kids who are solving these things in three seconds. Tell us about that distinction and problem-solving that the Rubik’s Cube can shed a light on.

AJ Jacobs: Yeah, I… One of the people I spent some time with was one of the original champions, way back in 1981 or two. And he is the one who wrote the book, “How to solve the cube in 45 seconds,” which now is like an eternity, but back then, that was a big deal. And he’s funny. He loves that kids love the Rubik’s Cube, but he’s a little grumpy, because he does say that it’s different. Back then, people had to discover how to solve the Rubik’s Cube. You had to create your own algorithm, your own way of solving it. And now you can go on YouTube and memorize a couple of dozen algorithms and solve it that way. So it’s a different skill. It’s sort of an exploratory and science versus memorization. And both are important. I admire both. But I do prefer puzzles where you have to come up with the solution in a totally new way and it doesn’t require as much memorization. So maybe I’m on the old fogey side, like this guy.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I’m kind of on the old fogey side, ’cause it kinda takes the puzzle out of the puzzle, if you just… You know what the answer is. If you just put these things, you’ll get it. I don’t know, it doesn’t seem as fun.

AJ Jacobs: Although I just wanted to defend these young kids ’cause it does require some… A lot of skill to figure out which algorithms to do, so that is a puzzle.

Brett McKay: Sure. Yeah. And I noticed with my kids too, they… YouTube is crazy. It’s great. I like how it motivates them to do things. But I’ve noticed that they’ll… My daughter’s really into Minecraft. And instead of trying to figure out how to build things on her own, she’ll just watch a YouTube video and just kinda pause and then do the thing and then watch it. And she builds this cool thing, and it’s… I mean, it took a lot of patience to do it, but it’s like, Yeah, I don’t wanna diss on my daughter, but I was like, “Well, you just watched a video on how to do that. It would have been cooler… I wanted to see what you wanted… If you were free building, what would you make?”

AJ Jacobs: Right. Well, it’s like the difference between Legos when we were kids and Legos now.

Brett McKay: Oh yeah.

AJ Jacobs: When I was a kid, it was just a bunch of blocks and you had to create something. And now they have these elaborate kits where you have to follow 150 instructions and get it. And they are both… They both have their benefits. So I don’t wanna be too much of an old fogey and in just following instructions to create this spaceship. But I still… I think I prefer the old type where you’re just given a bunch of random Lego bricks and you create yourself.

Brett McKay: So let’s talk about my favorite puzzle, which is the jigsaw puzzle.

AJ Jacobs: I love that you love it.

Brett McKay: So I’m curious, you’ve spent your time talking to people who make just really simple jigsaw puzzles to individuals in Vermont who make $100,000 jigsaw puzzles, hand-crafted, and you’ve been putting together a lot jigsaw puzzles. Did you figure out what it is about jigsaw puzzles that are… They’re so relaxing and soothing, but at the same time, they’re incredibly addictive?

AJ Jacobs: They really are. I know. I had that feeling when… It’s just one more. I’m just gonna get one more piece and then one more, and then it’s 3:00 in the morning. And it’s funny because I was a jigsaw puzzle skeptic, and I became a convert. And I don’t know why I was so snobby, but I, for some reason, hadn’t done them, and then I started to do ’em, and I was like, Oh yeah. And I think there are two different ways you can do jigsaw puzzle. One is as meditation. And I think that was big in the pandemic. I mean, jigsaws at the beginning of the pandemic, you couldn’t find them. They were like hand sanitizing. You couldn’t… And people just snapped ’em up because they needed that escape. And you can get into the flow and the hours just pass by like minutes. So that is one. But then there are the jigsaw puzzles where it’s more about trying to solve a really complex puzzle. And either that could be speed. There are people who are obsessed with solving ’em quickly. And I wrote in the book, one of my favorite adventures that my family and I went on was we went to Spain and competed as Team USA in the World Jigsaw Puzzle championship.

And we humiliated our country. I apologize to my fellow Americans. We came in second to last. But it was wonderful, ’cause you got to see these people at the top of their game, the LeBron James of jigsaws, and just how fast their minds and hands were moving. And it was remarkable. But then there’s another type of challenging jigsaw, which are the ones you mentioned, sort of these artisanal wood-cut jigsaw puzzles that are super tricky and have… And edge pieces look like regular pieces, there are 3D, there are pieces from other puzzles thrown in just to mess with you. And I learned to love those. Those you have to have… You have to know that frustration is gonna be a large part of it, but I find them just fun and weird and absurd and delightful.

Brett McKay: Yeah, my… I do jigsaws for the meditative purposes. That’s why I do them. And I was saying earlier, I’m very particular about my jigsaw puzzling.

AJ Jacobs: What do you like and what do you not like?

Brett McKay: Okay. So, well, there’s one, there’s jigsaw puzzle season, and it starts September 1st and goes through December 31st. That’s the only time I do jigsaw puzzles. And they have to be… I like the Americana folk art puzzles. Charles Wysocki is my favorite. And then I have to listen to my puzzle playing playlist, which is… It’s primarily schmaltzy, easy listening, and Muzak. So I’m talking like the Sedia Orchestra. I basically wanna feel like I’m walking through a Montgomery’s ward in 1987 when I’m doing puzzles.

AJ Jacobs: [chuckle] I’m relaxed just hearing about it. That sounds lovely. Yeah. That sounds fun.

Brett McKay: Yeah. But you highlighted some things like the same sort of things that… How to tackle puzzles that I’ve kind of picked up on on my own. You get that toehold. Sometimes you just start with the… If you see something that you can put together easy, start there, and from there you can build off. And then you have found some other little… Cool little tricks to put together jigsaw puzzles?

AJ Jacobs: Yeah. One that I did not expect, but these high-level jigsaw-ers, they don’t only do it by color. They also paid a lot of attention to the shape. And if you’re hit with a big blue sky and you don’t know what to do, they will sort the sky pieces by shape. So they’ll have a section of one outie and three innies and two outies and two innies, and they’ll have these little piles, and then, using those, they’ll be able to assemble it quickly. So I think that’s great. I just… I never thought of jigsaws as having a lot of strategy. But they do. At the high level, you can really separate yourself using these tricks.

Brett McKay: So you also did mazes. You talked about when you were a kid, you drew mazes on the ground that covered your whole apartment. I’m sure every kid has done that when they’re in class and they’re bored, they’d make their own maze on their folder. How long have humans been using mazes as puzzles? Did you figure that out?

AJ Jacobs: Well, yeah. Definitely millennia. There’s the myth, I don’t think it actually existed, of the Minotaur at the… In the middle of a maze in the Island of Crete. And that was a maze you didn’t wanna go into, because if you got lost, then the Minotaur would eat you. But they have been used… They’ve been used for spiritual purposes. People talk about how amazes are like prayer through walking. But then they’re also entertainment. In the Middle Age… Or, yeah, the Middle Ages or a little later, Europe had a ton of hedge mazes and people would have trysts in them. So they have a long history.

Brett McKay: And then you tackled one… Something that became really popular in America in the past, I would say, 25, 30 years, are these corn mazes. And you went to Vermont to tackle the largest, most complicated corn maze. Tell us about that experience.

AJ Jacobs: Yeah. I love this. This was the Great Vermont Corn Maze, it’s called. And it’s huge, 24 acres. And there’s no governing body that says, “This is the hardest corn maze,” but it seems that this is probably the hardest in America. And the guy who started it, Mike Boudreau, he’s a great guy, and just delightfully sadistic, though, he is… He’ll… He will gleefully tell you that people will weep, they’ll get lost, they’ll get in fights. One father drove… Abandoned his family, wife and kids, and drove off because he was so frustrated. And he says, “Don’t bring your teenage kids, because it’s too hard.” And it is… Yeah, I got… It took me over four hours of twists and turns. And there are all sorts of dead ends that will just mess with your mind. And I love it.

One of the things I loved was talking to him, because he says he stands up on a platform above the maze and watches like a God. He watches these mortals as they try to make their way. And he says it’s a real lesson in human psychology. And he says, “A lot of times, people,” he says, “Especially young men,” which I thought was telling, “Will have that cognitive inflexibility,” I was talking about. They are so convinced they’re right. So they’ll go down a corridor, they’ll hit a dead end, and they’re like, Okay. And then they go back and they go down it again. And they just keep going down that same corridor so convinced that they’re right, despite the evidence, the clear evidence that it’s a dead end. So mazes, like every other puzzle, and I think every activity, you need to be more flexible.

Brett McKay: You have talked about logic puzzles, and this reminded me, there was a period in my life where I became obsessed with logic puzzles because they’re part of the LSAT, the test you take to get into law school.

AJ Jacobs: I remember you did… Yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And so tell us about… What does a typical logic puzzle look like? And why would law school think you need to learn how to do these things in order to get into law school?

AJ Jacobs: Well, that is interesting. Do you remember any of the logic puzzles that you solved?

Brett McKay: Yeah. So there’s sort of things where there’s like, There’s five people, Sam, Alex, Jane, Brad, and they are going to bring five different items on these seven different days. And you had a clue like, Okay, Brad brought this on this day, but not on that day. And then you had to figure out who brings what on what day, that sort of puzzle.

AJ Jacobs: Right. That’s interesting. Yeah, I… There are lots of different types of logic puzzles. That one I think of it as sort of the Clue, the board game Clue.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s like Clue.

AJ Jacobs: And to me, the big lesson of those is they’re not that hard if you figure out how to diagram them. So it’s… If you do it in your head, then it’s a mess. But if you just diagram it correctly and you’re able to check them off, then it’s pretty easy. And I don’t know why the LSAT people put it in, I assume it’s because they think that it’s a sign of clear thinking and rational thinking, which I do believe. I don’t know how much it helps you as a lawyer. But there are lots of other types of logic puzzles. I am particularly a fan of the lateral thinking puzzles. I don’t know if you know those, the ones where it’s like a… There’s a man in a field and he’s got an unopened backpack on his back, and his face down and he’s dead. What happened? And you have to try to figure it out.

Brett McKay: My kids love those. My kids love those. Yeah.

AJ Jacobs: I love ’em. Yeah. And the answer to that one, just in… If you wanna pause it and try to figure it out, but he’s a parachutist and the pack didn’t open, so he fell. And then there’s other ones that are similar. I wouldn’t call them quite lateral thinking, but they do require some sort of leap of imagination. So, for instance, there are two girls in a classroom, and they were born to the same mother on the same month, the same year, the same day, but they’re not twins. What’s going on?

Brett McKay: Yeah. I remember my… Actually, my kids told me this one. I can’t remember. What is the answer?

AJ Jacobs: [chuckle] They are triplets. Or quadruplets. Could be quintuplets, you name it. So, yeah, I am a fan of the logic puzzles. And one of the people I interviewed, one of my favorite, was the Soviet mathematician who is… Well, formerly Soviet. She’s an immigrant. She came here and fled the Soviet Union. And she has a math blog called Tanya’s Puzzle Blog. And it is so… She has solved pretty much every logic puzzle ever created by humans. And one thing she talks about, she talks a lot about how you do have to think outside the box, but her students have taught her to think even farther outside of the box, that she’s in a box of her own. So the example she gives is, there’s a famous logic puzzle where there’s…

You have a basket full of five apples, and you give out all the apples to… You have five friends, and you give an apple to each of your five friends, but there’s still one apple left in the basket. What’s going on? And the answer, the traditional answer is that you give that last apple to a friend in the basket. You’re gifting them a basket in addition to an apple. A little bonus. So that’s why… But she says her students have come up with all these other creative possibilities, even one of your… Could be that the basket is your friend. Maybe inanimate objects are your friend. Or maybe one your… One of the five people died. So it’s… I love that idea that you can think outside the box, or you can think way outside the box.

Brett McKay: There’s another genre of puzzles you tackled, and that is ciphers and codes. And you went to the headquarters of ciphers and codes in the United States, to the CIA. And there’s an art installment there with this code on it that has not been cracked in over 30 years. What’s going on there? Why is there art with a code that can’t be cracked by the CIA at the CIA?

AJ Jacobs: Yeah, this was one… And that chapter was… I loved researching, ’cause codes are everywhere. That is… It’s why we can use credit cards, it’s… There’s… Cryptocurrency is all about codes. But the CIA, one of their stated purposes is to crack codes. And about 30 years ago, they hired a sculptor to create a sculpture on the grounds of the CIA headquarters in Virginia. And he teamed up with an ex-CIA cryptographer, and they created this work of art that’s a huge metal wall, and into it are carved hundreds of letters. And those letters, they’re… They look random, but they are a code. And even though it’s in the middle of the CIA, no one has been able to fully crack that code in all of those 30 years, including the CIA. They’ve cracked parts of it.

So we have parts, and some of ’em… Some of the code seems to be a longitude and latitude maybe of some buried treasure, some of it are quotes from the guy who discovered King Tut’s tomb. But there’s a part that is still unsolved. And what I love is that there are thousands of people, mostly in an online community, who spend inordinate amounts of time trying to crack this code. And it’s been 30 years, and they… Every day they have a new theory. Oh, I think it’s Morse code, I think it’s related to the Navajo Wind Talkers, all sorts of theories. But they haven’t given up. And it’s been 30 years, 32 years. And so I try to take that as inspiration. When I’m helping my kids with their math homework and I wanna give up after 45 seconds, I think, “You know what, these guys have been going for 32 years. Let me give it another couple of minutes.”

Brett McKay: But the world of code breaking and cipher puzzle solvers taught you a lot about the dark side of puzzles. What was that?

AJ Jacobs: Well, this is interesting. I think puzzles are all about finding patterns, and science is all about finding patterns, and that can be a great thing that has huge benefits, but we are wired, so hard-wired to find patterns that sometimes we find patterns that don’t exist, and that is… The word for that is apophenia. That’s the psychological word. And, for instance, finding the Virgin Mary’s face in a piece of french toast, that’s classic apophenia. And the problem with apophenia is you become attached to that pattern and you refuse to let it go, even if you are presented with evidence that it’s not true or it’s not going anywhere. So the key to avoiding apophenia is to keep your mind flexible. But apophenia has huge, real life repercussions, and I think it’s responsible for a lot of the problems we have right now.

So people are finding patterns in the world that don’t exist. It’s what can… A lot of conspiracy theories are basically solving puzzles that don’t exist. So, QAnon, they have found all these puzzle pieces and put them together, and they have “solved this puzzle”, but the pieces don’t fit together, it is not true, but they refuse to change their thesis no matter how much evidence they’re given. So apophenia is solving puzzles that don’t exist, and you’ve got to be very careful. So don’t fall in love with your hypothesis. Keep an open mind, keep flexible. That is the only way to battle this dangerous drive in our minds.

Brett McKay: And I think all of us experience apophenia on some level. It might not be conspiracy theory level, but I’m sure we’ve all encountered things where we think… We try to read people’s minds, for example, and we start seeing things like on what they’re saying or not saying or what they’re doing, we’re saying, Yes, this means they don’t like me, and they got this vendetta against me. And basically you’re just putting together pieces of information that are disparate and have no meaning to make meaning in your head.

AJ Jacobs: It’s so true. I mean, I’m sure that half of my beliefs are based on apophenia. And I’ve kinda tried to go through and think about them, but it is such a drive, and even during this year, solving puzzles; I remember I was doing a scavenger hunt, I didn’t even write about it, but one of the clues had to do with a mouse in Central Park and it had arches, and it just so happened I had seen Stewart Little 2, the movie, and it was Stewart Little had an airplane and he drove it through arches in Central Park, and so I was like, Oh, it’s gotta be Stewart Little, that’s the answer. And I went to Central Park and I spent hours trying to verify my… And it was totally wrong, it had nothing to do with the answer. But I was so attached to it, I couldn’t see through it.

Brett McKay: So one thing you’ve taken away from this book after researching and writing it is trying to take the lessons you’ve learned from puzzle-doing and puzzle-solving and puzzle-creating and applying it to life. Do you think it’s possible to treat all of life’s problems and challenges and annoyances as puzzles? Do you think that, is that something do you think we can do in our head, that and it can actually make things better?

AJ Jacobs: I definitely think that that frame can make things better. I don’t know about all problems and puzzles, but a lot of them. And I try to do it in my life. Quincy Jones, the great musician, he has a quote where he says, “I don’t have problems, I have puzzles.” And I think it’s so inspiring, because problems are thorny and depressing and insoluble a lot of times, whereas puzzles, they can be solved, and they are inspiring, you want to solve them, and even sometimes they involve playfulness. So I try to frame my life’s challenges as puzzles. How can I solve them? And one of the hardest puzzles we face now is just how do we bridge the gap between the culture, the culture war. That to me is a huge puzzle. And when I’m talking to someone from the other side of the political spectrum, I could try to debate them, but rarely, the sort of war of words, it rarely yields anything, in fact it usually polarizes both sides. So instead I try to treat it as a puzzle, and I say, You know, why do you believe what you believe? Why do I believe what I believe? Is there any evidence that we could change our minds?

Where do we go from here? Is there any common ground we have? Now, all those are puzzles that you can work on collaboratively in a conversation, and I think that’s much more likely to yield something useful than to berate each other. So, to me, one of the phrases I learned during the pandemic was, Don’t get furious, get curious. And I think that is a very nice little puzzle motto that I try to remember all the time.

Brett McKay: Have you tried to help your kids to take up the puzzle mentality with their life?

AJ Jacobs: Oh sure. And it’s a puzzle of how to get them to listen to me, which I have not solved that puzzle. [chuckle] But I do think… Yeah, if they are faced with something that… We often talk about the strategies we use in puzzling, like if they are faced with a big sort of term paper, well just take it step by step. Anne Lamott has that great quote, “Bird by bird.” Her brother had to write a paper on all birds in North America, and he’s like, What do I do? And their father said, Just do bird by bird. And that is a great puzzle strategy. Just one step at a time.

Brett McKay: Well, AJ, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

AJ Jacobs: I’m at ajjacobs.com, or the puzzlerbook.com, or I’m on Twitter at AJ Jacobs. And I would love to hear from folks about their favorite puzzles. And there’s tons of puzzles in the book for them to solve, so if they need hints on that, then they can also contact me.

Brett McKay: Well, AJ Jacobs, thanks for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

AJ Jacobs: My pleasure, and I hope to come back before episode, it would be like 1700.

Brett McKay: [chuckle] Right. We’ll make it happen.

AJ Jacobs: All right. Thanks.

Brett McKay: My guest there was AJ Jacobs, he’s the author of The Puzzler. It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find more information about his work at his website, ajjacobs.com. Also check out our shownotes at aom.is/puzzles, you can find links to resources or you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The AOM Podcast. Make sure to check out at our website at artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives as well as thousands of articles written over the years about pretty much anything you can think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code Manliness at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Spotify, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you would think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay. Reminder to you all listening the podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.