Every Christmas season, modern musicians — from pop stars to country singers to R&B artists — release new holiday music, offering their own versions of old songs and attempting to introduce new hits into the Christmas canon.

Despite this constant influx of new holiday music, people often continue to reach for a set of classic songs that are eighty years old.

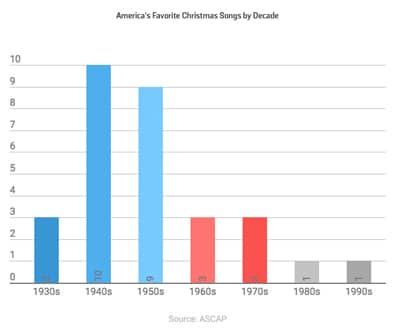

If you’ve ever mused that it seems like the most popular holiday songs largely come from the 1940s and 50s, that perception isn’t just in your head. Statistically, two-thirds of the top Christmas songs of all time came out during those two decades.

While the 1950s were big in terms of holiday pop songs (“Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree”; “Jingle Bell Rock”) and novelty songs (“Frosty the Snowman”; “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus”), it was the 40s (and the very earliest years of the 50s) that saw the release of the Christmas songs we consider the most classic of the classics:

- 1942 — “White Christmas”

- 1943 — “I’ll Be Home for Christmas”

- 1944 — “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”

- 1945 — “Let It Snow”

- 1946 — “The Christmas Song”

- 1948 — “Sleigh Ride”

- 1950 — “Silver Bells”

- 1951 — “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas”

Have you ever wondered what accounts for this phenomenon?

Part of what’s behind it is that Christmas really came into its own during the 40s, becoming a bigger cultural and commercial holiday than it had been. Companies spent more on holiday marketing. The genre of Christmas movies emerged (half of the above songs come from movies), and the films really solidified the music in the popular consciousness.

But the launch of a more all-engrossing holiday during the 40s doesn’t explain why we’re still playing this era’s songs today.

The staying power of this music comes down to a confluence of cultural and historical factors.

First, the style of music that was popular during the 40s simply seems to fit the feeling of the holidays best — better than the style of contemporary music does.

Jazz was the most common genre of music during the 1940s. Jazz harmonies are composed of more parts than the average modern pop song, which employs simpler harmonies. As Brian Earl explains on the Christmas Past podcast, this gave songwriters of the era a wider and more complex musical palette to draw from, and the result is harmonies that have a more poignant effect on the listener.

Earl points out that the style of singing that marks the 1940s Christmas classics plays a role too; advances in microphone technology changed how songs were sung during that decade. “Ribbon mics were introduced that picked up a broader range of frequencies and allowed singers to get closer to the microphone and sing in a softer, smoother way. The crooner style flourished as a result.”

In addition to the jazz-y, crooner style of 1940s music being particularly suited to the inherent mood of the holidays, the historical backdrop in which it was made lent it an incomparable poignancy.

The Christmas classics of the 1940s were composed during and shortly after World War II. Soldiers overseas were missing home, and families in the States were missing their sons, brothers, and husbands who were serving abroad. The cultural atmosphere was marked by fear and hope, longing and yearning. People sacrificed, were haunted by death, and experienced life’s sharpest realities. As a result, the holiday music made during the period — both the new songs that were written and the traditional carols that were covered — is imbued with a well-earned sincerity and deeply felt sentimentality that feels palpable.

And unreplicable: even when contemporary artists attempt to put aside the present-day filter of irony, cynicism, and wink-wink knowingness to cover the mid-century Christmas classics, even when they try to adopt the crooner style of old, the same gravitas and poignancy that defines the songs of the 40s just can’t be duplicated by someone who exists in the modern milieu. If there hasn’t been another true Christmas classic — outside 1994’s “All I Want for Christmas Is You” — minted in the last eighty years, it’s perhaps because we’ve collectively lost access to the unmanufactured earnestness that’s essential for their creation.

Some say the holiday classics of the 1940s have stuck around because they constituted the soundtrack for Baby Boomers’ childhoods and that this large demographic cohort continues to perpetuate their popularity today. But personally, the classics have become such a big part of our own lives that even if every Baby Boomer suddenly disappeared from the earth, we’d continue to listen to these songs year after year; it wouldn’t be Christmas without them.

The staying power of the old classics isn’t due to a particular generation’s nostalgia for childhood. It isn’t, in fact, about any generation’s nostalgia for childhood, or even for a historical era in time. There is an existential nostalgia, a desire for homecoming, felt in the soul that doesn’t attach to any particular period — a painful-yet-pleasurable yearning in everyone, of every age, for we-know-not-what.

The songwriters and musicians of the 1940s, who had lived life at its highest pitch and experienced both its darkest shadows and most incandescent light, were able to capture this yearning in a uniquely poignant way. Year after year, we play their songs again to feel those bittersweet stirrings for ourselves.

To learn how many other Christmas traditions came to be, listen to our podcast with Brian Earl: