The Twilight Zone is arguably one of the best and most influential shows in television history. The reason it endures, and is still being watched and talked about more than sixty years after its debut, can not only be traced to its superior storytelling and innovations in the genres of horror, science fiction, and fantasy, but the fact that each episode is embedded with a lesson on how to grapple with life’s moral and existential dilemmas.

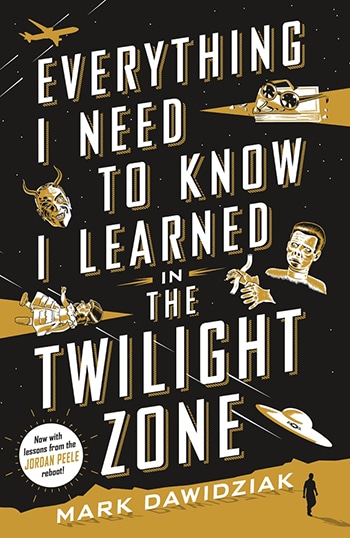

Here to unpack those life lessons is Mark Dawidziak, author of Everything I Need to Know I Learned in the Twilight Zone. Today on the show, Mark and I discuss the parable-like morals from a selection of Twilight Zone episodes, drawn from those that are my favorites, Mark’s favorites, and simply classic. And, since Halloween is coming up, Mark and I both offer our picks for the just plain scariest episodes to watch.

Resources Related to the Episode

- Episodes referenced in the show:

- “A Stop at Willoughby”

- “Walking Distance”

- “Time Enough at Last”

- “A Nice Place to Visit”

- “To Serve Man”

- “Mr. Bevis”

- “Kick the Can”

- “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street”

- “The Obsolete Man”

- Mark’s picks for the scariest Twilight Zone episodes:

- “Twenty Two”

- “Ring-a-Ding Girl”

- Brett’s picks for the scariest Twilight Zone episodes:

- “Living Doll”

- “The Dummy”

- “It’s a Good Life”

- AoM articles inspired by Twilight Zone episodes:

- Can’t Have the Sweet Without the Bitter (Inspired by “A Nice Place to Visit”)

- How Redundancies Increase Your Antifragility (Inspired by “Time Enough at Last”)

- Sunday Firesides: Things Don’t Get Old, We Do (The illustration is an Easter egg homage to “Walking Distance”)

Connect With Mark Dawidziak

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. The Twilight Zone is arguably one of the best, most influential shows in television history. The reason it endures and is still being watched and talked about more than 60 years after its debut, can not only be traced to its superior storytelling and innovations in the genres of horror, science fiction and fantasy, but the fact that each episode is embedded with a lesson on how to grapple with life’s moral and existential dilemmas. Here to impart those life lessons is Mark Dawidziak, author of, Everything I Need to Know, I Learned in the Twilight Zone. Today in the show, Mark and I discuss the parable-like morals from a selection of Twilight Zone episodes drawn from those that are my favorites, Mark’s favorites and simply classic. And since Halloween is coming up, Mark and I both offer our picks for the just plain scariest episodes to watch. After the show is over, check out our show notes at aom.is/twilightzone.

Alright, Mark Dawidziak, welcome to the show.

Mark Dawidziak: Well, thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: So you wrote a book a few years ago called, Everything I Need to Know, I Learned in the Twilight Zone, and this book grew out of… You had been… You had introduced your daughter to the classic television shows you love, and when she was a teenager, you decided it was time for her to watch your very favorite television show, which is also one of the favorite shows in my family, and that’s the Twilight Zone. And as you watch the show together, you found yourself discussing life lessons that were embedded in the episodes and realize the Twilight Zone, it really offers a good guide for life. There are parables and morality plays in the episodes, and so you wrote a book about those lessons. And I think it’s interesting. You watch this with your daughter, she loved it. You mentioned in the book that you’ve taught classes, college classes, and when you mention classic television, kids are not… They don’t know who the Honeymooners are anymore, The Andy Griffith Show has fallen out of the collective pop culture consciousness, but when you mention Twilight Zone, the kids still know about Twilight Zone. My kids, they’re 11 and they’re nine, they’re loath to watch anything in black and white, and I’m like, “I wanna watch these classic movies, they’re black and white.” “No, I don’t wanna watch that.” But Twilight Zone, they’re all over it. They love the Twilight Zone. So what is it about the Twilight Zone that gives it such timeless, cross-generational appeal?

Mark Dawidziak: The Twilight Zone was, is and forever will be great storytelling. And you’re not asking somebody who is young, when you introduce this to them, you’re not asking them to watch a 90-minute, two-hour movie, you’re asking them to watch a half-hour episode. It’s easily digested and it has the appeal of sitting around the campfire of, “Let me tell you a story.” Well, who doesn’t wanna hear a story, well, and especially youngsters. And I discovered the Twilight Zone when I was very young. I discovered the Twilight Zone when I was not old enough to have seen it in its original run. It ended in ’64. I was about seven years old, seven going on eight when it ended its run, so I was too young for it, but, but I grew up in New York and a station there, WPIX Channel 11, immediately started re-running the Twilight Zone, and I started watching it at about the age of 10 in reruns, and I loved it for the reason probably most kids my age would have first loved it. I didn’t know there were morality tales in these things, I didn’t know there was something metaphoric going on behind this, I was watching it for the spook out factor.

It had that same appeal of, you remember when you were a kid and you try to creep out your friends with those urban legends that everybody knew, that always existed everywhere, and always said, “And the only thing that was left, they found the hook on the bumper of the car, ooh.” Those kinds of stories. That was the appeal of the Twilight Zone for me at 10 years old. And I loved it because I had become a horror fan at seven years old, I loved the old Universal horror movies, I loved anything that was like that, the 1950 science fiction movies about giant creatures sacking major cities, I loved it all. And here comes the Twilight Zone, and it gave you a daily creep out, and who didn’t want that at 10 years old? And then when I was a teenager, I started watching them and then you start to sense, “There’s something more going on here. There is something going on behind all of this sort of creepiness.” So the Twilight Zone can hook you when you’re very young. Just as it hooked me as a 10-year-old in 1966, it can hook a 10-year-old today for the very, very same reason.

It has that wonderful, amazing, fantasy storytelling aspect to it, and why wouldn’t it? The principal writers were Rod Serling, Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson, which, it’s like the 1927 Yankees, a fantasy storytelling that was working on the show. So that’s the… I think that’s the short answer. And then you also have great performances. You had these great dialogue written by these great writers, and then they handed it to these great actors. Twilight Zone brings a lot of storytelling heat, and that’s very, very appealing to all ages, and you can age up with the Twilight Zone. So you can be watching it at 10 and just saying, “Well, this is a creepy show, I love it.” Then at 13, 14, you can start to watch it and realize there’s something more, and then as an adult, you realize these are life lessons that you can carry with you all the way through. So it’s just got a tremendous amount of appeal to it, and time… The proof is in the pudding because we’re talking about a black and white show that started in 1959.

Brett McKay: Yeah, good, yeah, good storytelling is transcendent. It’s like fairy tales. We all know these fairy tales, and I think people will still talk about the Twilight Zone a 100 years from now.

Mark Dawidziak: I agree. And I think one of the things that gives it that sort of intellectual grit is exactly that, is Rod Serling figured something out with the Twilight Zone. I tell this in the book. This is… And it’s no secret, anybody who writes about the Twilight Zone can’t get away from the fact that when Rod Serling started his career in broadcasting and radio and television in the late 40s and early 50s, television in particular was still the Wild West. It was a new medium. There were no rules. They were making it up as they went along. You could do just about anything if you could figure out how to do it with no money and no budget and no special effects and no stars. If you could figure all that out, you could do anything.

And as the 50s progressed, television grew up, and by the end of the decade when there were no rules at the beginning of the decade, by the end of the decade, it was nothing but rules. And all of a sudden it was getting harder and harder for Rod Serling, who had made his name as one of the angry young men of television, he and Paddy Chayefsky were probably the two leading writers in the era, what was then called the golden age of live drama. And by the end of the decade, it was getting almost near impossible to get the message out. Everybody would be… Was like, “Well, the sponsor won’t like that. The stations in this area of the country won’t like that,” or “The censor won’t like that.” And it was becoming very, very frustrating.

So Rod Serling took a calculated risk. He fled into the Twilight Zone, and he took a gamble. And the gamble was basically, I can write about the very same themes I’ve been writing about realistically all this time, all of the great themes of Rod Serling’s career prejudice, how we treat children, how we treat old people. I can write about all of that. And the sponsors and the censors will not lift an eyebrow as long as it’s couched in fantasy. And, [chuckle] he was right. The Twilight Zone addresses all of those things, and he didn’t have any problem getting the message across anymore. And in the book I call Rod a moralist in disguise, and that is actually an expression that comes from Mark Twain. And it actually comes from a letter that a little French girl sent to Mark Twain in the last decade of his life.

A very perceptive young woman named Helene Picard, who wrote him essentially a note saying, “I know the world knows you as a funny man, but I detect that behind all of the laughter and the humor is a very serious person who’s trying to teach us something.” And Mark Twain wrote back to this amazing young woman in France, a letter which basically said, “Shhh, you’ve got it. You’re on it. You’re 100% correct. Don’t tell anybody, but I am a moralist in disguise.” Now, is there a better description for Rod Serling than that? Basically what Mark Twain did with humor, which was Mark Twain once said that, “For humor to live, it must not professedly teach and it must not professedly preach, but it must do both if it will live.” In other words, the moral had to be hidden. The moral had to be hidden behind the laughter.

And so what Rod Serling did was Rod Serling used fantasy the way Mark Twain used humor. He hid the message in fantasy. He was like Mark Twain, a moralist in disguise. And so each Twilight Zone, especially Rod’s, contained what I would call a parable. Now parables are storytelling. And it’s a great way to teach somebody a lesson while entertaining them. And you wanna say to yourself, “Now, where have I heard that before? Where have I heard this whole notion of parables of being moral lessons?” And you might say, “Oh, oh, oh, you mean the New Testament you’re talking about Christ?” Well, actually, you can go all the way back to the Greeks in Aesop. It actually even goes back farther than that. The best way to sort of get every Aesop’s Fable ended with the unsaid words and “the moral of the story is… ” And you could say the same thing about the Twilight Zone.

Brett McKay: Right. He who has ears to hear let him hear. That’s what Rod was trying to do.

Mark Dawidziak: Right.

Brett McKay: And I think that’s a good point you make about the Twilight Zone. Like he was a moralist in disguise. And what I love about the Twilight Zone, I’ll watch some other TV shows or movies where it’s obvious there’s some sort of moral message or philosophical message they’re kind of trying to convey. But it always feels ham-fisted, feels like they’re just beating you over the head with it, and it doesn’t land as much. And when I watch The Twilight Zone, I always… When I’m done with an ep, like a good episode of The Twilight Zone, not all of them are great, but like a really great episode. You’re left kind of disturbed and disoriented and like you stew on it for days, weeks, sometimes there’s like episodes I think about just years after I’ve seen it, I’m still thinking about it.

And I think that’s the talent, the talent and the expertise of Rod Serling, those other writers. Oh, so let’s dig in some of these lessons from The Twilight Zone. There were 156 episodes during its five season run. So there’s a lot to choose from. So I thought to narrow it down, I’m gonna focus on the episodes that have had the greatest impact on me and my family. So I’ll start with two episodes that Kate and I, my wife, we reference quite a bit to each other. And it’s Walking Distance and A Stop at Willoughby. And you make the case that these two episodes are part of a character progression and a theme development that certainly began even before Twilight Zone. But let’s talk about these two episodes first. Let’s talk about Walking Distance, Reader’s Digest version of this story. What is this? Oh, I guess we gotta do the spoiler alert. If you haven’t seen The Twilight Zone, you should probably stop listening right now and go watch it and then come back and listen to this. So there we go. You got your spoiler alert. So, Walking Distance what’s the Reader’s Digest version of this story?

Mark Dawidziak: Gig Young plays a businessman in his 30s, a burned out business man who is being driven into the ground by the rat race and the New York lifestyle. And he is driving and his car breaks down and it happens to break down just about a mile or two from the town where he grew up. And so he leaves the car with the mechanic to be fixed, and since he has some time on his hands, he decides, “Hey, that’s walking distance. I can walk back to my home town and see what it looks like now.” And he indeed walks not only back to his home town, he walks into his own past and encounters himself as a little boy, and the hometown that he knew then. One of the inspirations for this is that every summer, Rod Serling would pack up everything, and his family, his wife and two daughters, and he would spend the summer on Cayuga Lake at the family cottage on the lake, and they would spend these idyllic summers. He actually got a great deal of writing done during that time. And he would always take one day during every summer to go back to Binghamton, which is where he grew up, and that episode is basically about Binghamton where he grew up. And the park where you can go to today, if you ever get to Binghamton, go to Recreation Park.

Recreation Park, Rod Serling was born on December 25th, 1924. Recreation Park was opened a few months later. They grew up together, and it had a carousel, it had a band stand, it was the idyllic place of summer recollection for Rod Serling. So that episode is extraordinarily autobiographical. The character was about Rod’s age when he was writing it, and he was feeling burned out by… He had accomplished a lot, he had done a lot since the end of the war as a writer, and he always had this… Felt this pull on the past, the nostalgia of his childhood, and that’s what that episode is about. And it is an amazing… I would venture to guess that if you could have asked Rod what his favorite episodes were, he might have named Walking Distance and Stop at Willoughby. They are certainly, Rod’s daughter who is also a very fine writer and Serling and wrote the foreword for my book, I think Anne, those are, two of Anne’s very, very favorite episodes too as well.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and Walking Distance, so Martin Sloan, he goes back to his childhood and it seems like he gets frustrated ’cause he wants to go back there and kinda re-create it, and then everyone there is like, “Who is this weirdo? This 36-year-old man saying that, he’s this… My son, who’s actually 12 or whatever, nine.” And then his dad, finally… The Martin Sloan’s dad finally realizes, “Okay, I think you actually are my son from the future.” And his dad said, “Look, I know it might be hard. You’re having a hard time in your life, but you can’t go back, you can’t live in the past, you have to create those good memories for yourself in your life. This is done. You have to move on.”

Mark Dawidziak: There’s an amazing exchange. The dad says, “Is it so bad where you are?” And Martin says, “I thought so.” And the dad says, “Look around, you might find summers there too.” And I think that’s an amazing… You have to live in the moment. You have to live… You can’t live in the past, you can’t… It’s one of the great episodes of… Lessons of that episode, is you can’t… You can love the past, you can appreciate the past, but you can’t live in the past. We’re doing this interview, that was one of my mother’s favorite lessons to us when we were growing up, as we were getting older was to… She always talked about living in your time and living in your moment and not living in the past. And today is actually my parents’ wedding anniversary, [chuckle] so it has a sort of a pull for me too.

Brett McKay: And then in A Stop at Willoughby, same sort of theme. You have this guy in his 30s, late 30s, super successful, but he’s just getting beaten down by the rat race. And my wife, whenever we feel like really busy, we always, you know, we got work and then there’s kids, we gotta be out late and we’re like, “Push, push, push.” Like the boss in that episode. Push, push, push all the way. Push, push, push. And to escape this, this guy goes to this idyllic past that he never actually lived while sleeping on a train on his commute.

Mark Dawidziak: Yeah. He falls asleep on the train, he wakes up and the train is an old-fashioned train and the conductor is your old-fashioned conductor, and he’s yelling out, “Willoughby. Next stop Willoughby.” And the train pulls in and then he awakes and he thinks, “Was it a dream? Was it not?” And as things get worse and worse for him he’s determined to get off at Willoughby. He’s determined to find that idyllic place, and it’s a very, very bittersweet episode as we both know, because it ends… Like a lot of Twilight Zone, it ends in a way that’s sort of open to interpretation, is what happened? What exactly happens? Is that a happy ending to Willoughby or isn’t it?

Brett McKay: Yeah. No. [chuckle]

Mark Dawidziak: You know?

Brett McKay: Great. Sometimes you’re having those moments like, “I wanna get off at Willoughby.” And you’re like, “Wait a minute. No, maybe I don’t wanna get off at Willoughby.”

Mark Dawidziak: Yeah. It’s a really interesting… Or is he in better place? Do we envy Martin? The last thing we see of Martin is he’s in this other realm, he’s in this other place and he’s having this sort of Huckleberry Finn existence that he’s dreamed of, and again, I’m not so sure it is as downbeat an ending as a lot of people think, but it is… He did… One of Rod’s recurring themes was how people get used up and we cast them aside, and he basically talked about business doing that, and he’ll talk about it again. His first great piece for television was Patterns, which was aired about five years before the Twilight Zone premiered. And Patterns sort of addresses this issue of when you’ve taken all the talent somebody’s had and you’ve pushed them to the extremes and they’ve given you everything they have, how do we treat them at that point? How do we reward… Do we just cast them aside as Arthur Millers says in Death of a Salesman, like a piece of fruit, like a dried up thing? Do we just cast that aside then? And Rod is always sort of talking about that, he talks about…

I don’t know how many writers in the 1950s and the ’60s and even today, sort of talk about how we treat people as they get older and maybe they lose a step. And the Twilight Zone was always sort of talking. That recurs in a lot of episodes of how we treat aging parents, how we treat older people, and how we treat the most vulnerable people in our society, how we treat children. That’s another theme of the Twilight Zone, that comes back a few times. And I think it’s something we all can relate to because we are… We’re pushed into careers. We all get pushed hard. There’s always a lot of stress. And there is this kind of, “Wow, wouldn’t it be nice to escape? Wouldn’t it be nice to go to a place like Willoughby, where you can live your life to the full measure,” as they say in the episode. And I think it’s a beautifully crafted episode.

Brett McKay: And what’s interesting about those episodes, you’re not left with solutions about the problem, but you’re less thinking about and stewing on. I think like Willoughby will come up throughout my life where I’m having a busy moment. I’ll think about Willoughby. It’s like, what does Willoughby got to teach me? So I think that’s one of the geniuses of Rod Serling. Another iconic Twilight Zone episode is “Time Enough at Last.” Give us a summary of this show and then talk about why… In the book you said this is one of your least favorite episodes, even though it’s iconic. You gotta talk about why you don’t like it.

Mark Dawidziak: I don’t want that to sort of color that because I… It’s not one of my least favorite because I really like almost everything about it. I like the way it’s shot. I like the Glee performance. I think it’s… Burgess Meredith plays a fellow who loves to read. He is a teller in a bank, and his boss, his wife, everybody, these very unpleasant people basically want him not to read. They’re always trying to stop him from reading. So he spends his lunch break in the bank vault, and when he does, there is a nuclear exchange. The world is destroyed and he is saved. He is the last man on earth. And he walks through the rubble and he realizes everybody’s gone. And he even contemplates suicide until he sees the library and he realizes this can be his survival.

He can go through eternity. There’s books forever he can read. And he now has time to read. There’s time enough at last. And as he is stacking the books up on the steps of the library, the glasses slip… His reading glasses slip from his face and shatter. And he picks the glasses up and says, “That’s not fair. There was time, at last there was time enough at last.” Now it is probably the most iconic Twilight Zone episode as far as, O. Henry type of ironic endings go. It is probably the most powerful and it has probably the most powerful visual image of the Twilight Zone, the broken glasses. So I appreciate it on all those levels, but it is an outlier. And when I say that, is the Twilight Zone worked according to a certain set of rules. And one of the rules was that you were rewarded and punished by what you brought into the Twilight Zone.

If you brought in kindness, mercy, empathy, a caring for children and older people, if generosity, if you brought all of that into the Twilight Zone, you were rewarded for it. On the other hand, if you brought in greed, if you were mean, if you were a bully, if you brought in all of the nasty aspects of the human existence, you were punished for it. The fellow in “Time Enough at Last” to me, to my mind, did nothing to merit that awful ending. What is his crime? He wants to read. Well, how dare he? So it’s an outlier, it’s a powerful episode. And I don’t want people to understand that I don’t like it, but I do think it stands out because it’s one of the episodes that does not really play according to the rules of the Twilight Zone.

Now, having said all that, I could not ignore that episode when I wrote the book and I could not, not come up with a life lesson for it. And the life lesson was, again, was supplied by my mother and the life lesson I put on it, which I think is a valid life lesson. When we were kids and there would be squabbles among us as we were five kids growing up. And as there were squabbles, if it was not settled to one of us, our satisfaction, we would say, “But that’s not fair.” And my mother’s favorite expression was, nobody said life was fair. I hated that when I was a kid. I didn’t really like it in the Twilight Zone either, but I acknowledge it as the truth. Life isn’t fair. And nobody said life was fair. And that’s what Burgess Meredith’s character says at the end.

He says, “That isn’t fair.” And we agree with him, it isn’t fair. So that’s my take on that episode. And by the way, Anne Serling agrees with that 100% [laughter] She’s another one who just feels like the payoff is not… It does not fit any crime. He does not really commit a crime. Now I’ve heard people say it’s really about the fact that he is so absorbed in books, he’s cut himself off from other people. And that is a legitimate interpretation of the story. And if that’s your interpretation, no, you can’t be wrong in your interpretation. I don’t happen to agree with it because of how the characters are played. The wife may be the most evil person in the whole history of the Twilight Zone, and that’s saying something. That awful unpleasant, who commits one of the worst crimes when she takes his book of poetry and says to him, “Here, read some poems from this, from me.” And he’s delighted because he thinks, “Oh, she finally gets it. She finally understands my love of the written word in poetry.” And he opens the book to see she has defaced every page. She has gone to the extent of making every page unreadable. I don’t know if there is a more despicable act in the history of the Twilight Zone than that. That goes beyond mean. So, no, I don’t buy that, as far as an explanation, but again, it’s my life lesson, and I think it’s a valuable life lesson.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. Another episode that Kate and I reference again and again to our kids and to each other is “A Nice Place to Visit”. What’s that show about? What do you think is the lesson from the show?

Mark Dawidziak: Let me back up on that one, on “A Nice Place to Visit”. Why is that one particularly resonant to you?

Brett McKay: Okay, so I guess we gotta talk about… Let’s do the summary of the show, right?

Mark Dawidziak: Okay, alright, alright.

Brett McKay: So, you give us… You’re the expert, so give us the summary of the show, and then we’ll talk about why it resonates with me.

Mark Dawidziak: It’s the episode where… It’s where the criminal gets shot. You know… It’s Larry Blyden, it’s one of Larry Blyden’s two performances on it. And he plays a street thug just as common a criminal as you possibly can have, and he gets gunned down during a robbery, and what he assumes is an angel appears, who just calls himself Pip, played by Sebastian Cabot. And he is there to give him everything he desires, everything he wishes for. And he gets the nicest apartment, women throw themselves at him, he got all of his life desires. Every time he plays a game of chance, any gambling, he wins. Every slot machine pays off. And at the end, he’s bored. He becomes absolutely bored with the fact that he’s got everything he wants. And he says to the angel that he doesn’t even understand how he ended up here, that maybe he should have been sent to the other place, and the angel starts laughing and tells him, “But this is the other place. You are in hell, and this is going to be your hell.” So now, I am dying to know, if you’ll pardon the expression there.

Brett McKay: Okay.

Mark Dawidziak: I am dying to know why that one [laughter] so appeals to you and your wife.

Brett McKay: Well, it’s the idea that you can’t know the sweet without the bitter, or you… And yet, there has to be an opposition in all things, like if you wanna know what hot is, you have to know what cold is, and we tell our kids when life just is “You get whatever you want”, it becomes flat, and I think… It resonates with us kind of in our… This age of algorithms giving you whatever you want in terms of content, and then you can get Amazon shipped to your door in a day. We’re kind of creating worlds like this mobster of ours, you just get whatever you want catered to you. And people are like, “My life just feels existentially flat,” and I’d say, “Well, that’s… It’s probably because of this. There’s no friction in your life, and you need that.” That’s our takeaway from it.

Mark Dawidziak: And I agree, you know, that… It goes back to another Mark Twain quote, which is, Mark Twain once said something that… Along the lines of, happiness ain’t a thing in itself. Happiness is just a comparison to something that ain’t happy, that you need both. How would you have any gauge as to what’s happy if that’s all you knew? That you have to have misery in your life, you have to have tragedy in your life to understand what happiness is. There has to be a contrast. So yes, that is true. And I think that’s one thing that’s true about the whole Twilight Zone is that The Twilight Zone was very good at sort of blending light and dark. Nothing ever works. Darkness is always pierced by light in The Twilight Zone, and the flipside of it is that darkness is always lurking there, no matter how light you think something is. And it’s interesting, ’cause it’s a black and white show, so the contrast works extraordinarily well in The Twilight Zone. But that’s… The episode… And I put one of the lessons, the more obvious lessons I put on “A Nice Place to Visit”, was that if something is too good to be true, it probably is.

And I think that that’s entirely… You know, everyday and as your kids get older, they’re gonna have to be even more wary of this than we are. Everyday, there are scammers out there trying to find a way in by presenting something that looks too good to be true. And they’ve become very sophisticated about this, and they’re getting better and better at it. And everywhere you look, there are people who are basically trying to present something which is too good to be true, and The Twilight Zone told us very early, be wary of anything that’s too good to be true. If it looks too good, it probably is too good. And so there’s sort of that too. I mean, I think that that’s a sort of this… Because one of the great, also, things about The Twilight Zone is there’s always multiple lessons you can put on, and interpretations on, you can put on Twilight Zone, and my interpretation may not agree with your interpretation, which is good, because you’re bringing your life experience, your belief systems, your attitude to the episodes that you watch. So your interpretation of The Twilight Zone probably won’t always be the same as mine. That’s what the great thing about metaphoric storytelling. A primary example of this is the first chapter of the book that I wrote. It’s not the first chapter in the book, it’s the chapter I wrote as the sample chapter to sell the book to the publishers. And it was the one on “To Serve Man”.

Brett McKay: Yes. That’s another one of those…

Mark Dawidziak: Now again, one of the most striking, iconic episodes, right?

Brett McKay: Yes. We love that episode, yeah.

Mark Dawidziak: And I think I put maybe seven or eight different interpretive lessons in that chapter, that it could be… Some of them were funny and a little flip, and some of them were more profound, but they’re all in there. It’s not like any one of them is illegitimate as a possible interpretation of… I think the main one I put on it was “Never judge a book by its cover,” and that was somewhat being a little humorous with it, but it could be viewed as basically a retelling of the Trojan Horse. You could very easily just watch that episode that way. But again, there’s some episodes which you could look at and you could easily come up with five or six different interpretations for them.

Brett McKay: Yeah, “To Serve Man”. So it’s similar to that. If something’s too good to be true, it probably is. So the story there is aliens come to Earth, and they basically said, Humans, we’re gonna give you everything you want, there’s just books as to serve man on it, and we’re gonna give you everything you want, you can go to this planet and you’re gonna be fed, you’re gonna live… It’s gonna be great. And then in the end they find out there’s these decoders who are trying to decode the alien language, and they finally realize to serve man is, it’s actually a cookbook, it’s a recipe book on how to serve man to these aliens to eat.

Mark Dawidziak: Right, and the Kanamits is the name of their race. And again, they arrive promising peace, prosperity, and an end of hunger, and an end of drought, and all… This is like, there it is. If that ain’t too good to be true, I don’t know what is.

Brett McKay: Another episode you mentioned a lot in the book, is “Mr. Bevis”. And when we initially watched this one, we didn’t like it. My wife and I didn’t like it, and I think it’s probably because we’re probably too much of practical squares, but Mr. Bevis is… Just his weirdness kind of it annoyed me, and I kinda felt like he needed to get his life together, get a steady job, just act… Quit acting like an oddball. But after stewing about this episode for a while, I’ve come to appreciate the lesson from the show. So talk about… What’s the story of Mr Bevis, and what do you think the lesson is? And why did you… It seems like you’re drawn to that one quite a bit.

Mark Dawidziak: Yeah, I am actually. Mr Bevis is… He’s an oddball, he is an eccentric, he is played by Orson Bean. He likes all the strange stuff like zither music, and it’s odd because one of the things they say he likes is he likes the works of Charles Dickens, and it’s like, How is that so odd? Maybe in 1959, 1960, somebody drawn to an author from the previous century seemed odd, I don’t know, but he is out of step with the world, he’s out of step with what the world is supposed to be like for a young man in around 1960, and he’s out of step at work, he’s considered… But the children love him because he is this kind of grown child himself, so the children of the neighborhood love him, his co-workers love him because he is… His boss hates him, but the co-workers love him because he is warm, and he is funny, and he is an accepting down-to-earth person, and it’d be tough not to like him if you encountered him as your co-worker or such.

An angel played by Henry Jones appears and basically, on the worst day of Mr Bevis’ life says, you can have anything you want. He offers him whatever he wants, and of course, everything the angel gives him makes Mr Bevis more and more unhappy because it takes away the lifestyle that he was happy. He was not successful but he was happy, and he understood what it meant to be happy, and that did not mean position and money, and power, and all of those things. And at the end, the angel sort of understands this and restores his life to the way it was. I think among Twilight Zone fans, this is not considered a favorite episode, this would probably come out very low. It also falls under the category of the fact that there’s a general consensus that Rod’s comedies were not as strong as his other types of stories on the Twilight Zone. By and large, true, although he did write a couple of really good comedies and Mr. Garrity and the Graves is a Serling example of how he could write comedy and be successful with it.

But this one, I think people thought it was a little bit… And I would have to… One thing I wanna say is, one thing I did not do in the book was, I treated these episodes for the metaphoric storytelling, not so much the quality of them. Would I rank Mr Bevis among the finest Twilight Zone episodes of all time? No, I would not. Do I like the message? Oh yeah, I like it a lot. I do. Maybe because I feel like that’s kind of one of my roles in life is that I’ve always been a little bit out of step. I have not lived my life in step with me, and that also it does make you a bit of an outsider and you are gonna be rewarded for that. I would… I always used to tell my students that can state this, is that there’s a price to be paid for living life in your own way, and there are rewards for it, and hopefully the rewards will outnumber the drawbacks to living a life that is not prescribed. So yes, I do like the message of that episode, a lot.

Brett McKay: Another theme you see throughout the Twilight Zone is this idea of recapturing the magic of childhood. So I think that Mr Bevis kind of plays on that a bit, but one episode that really captures it is Kick the Can.

Mark Dawidziak: Yes.

Brett McKay: Summarize this episode, and how has this episode helped you reconnect with the magic and playfulness of childhood?

Mark Dawidziak: Well, Ernest Truex plays… He was a wonderful actor, and he’s also in another episode, What You Need as the peddler who can always give people what they need out of his box of goodies. But he plays in the resident of an old folks’ home, and it opens, he thinks his son is going to come and take him home, and the son arrives to tell him basically, there’s no room, he’s misunderstood him, he has to go back into the old folks’ home. And he sees a bunch of kids playing Kick the Can and it starts him thinking that maybe you get old when you start to think you’re old.

You get old when you stop playing. And he sort of thinks maybe the secret of life is Kick the Can. What if all of the residents could all play Kick the Can one night? Could they recapture their youth? Could they recapture the magic of youth? And his best friend tells him, “You’re old, you’re going to break a bone. What’s the matter with you? You’re acting like a fool.” And there’s an old saying, you get old when you stop playing games, not through… You basically, when you’re not in touch with your youth, that you’re no longer mentally young. And he tries to convince his friend to have an open mind and play Kick the Can, and the friend refuses, and of course it works and the residents are all transformed into children, except his best friend, who pleads with the children, “Take me with you.” And they run off because they don’t recognize him anymore. And I think that that is a powerful episode. It really is. And it’s not a Rod Serling episode, it’s a George Clayton Johnson episode.

But the writer who contributed to The Twilight Zone, who was closest to Rod’s philosophy and view of life, I think was George Clayton Johnson, and that episode really… It’s beautifully performed, it’s just a wonderful cast, and this notion that we now say, “You need to be in touch with your inner child, you need to be… ” And I agree with that, it’s just… It’s a difference between valuing the inner child and not being childish, but not living your life in a childish way, but never to lose sort of the child-like wonder that you had. And I think that’s very much what that episode is about. It’s not just about how we treat the older people in our lives, that’s certainly part of it, but there’s another part of it which talks about the magic of retaining… A GK Chesterton who was a wonderful writer, and I’ve always loved reading Chesterton. Chesterton once said that, “Nobody achieves greatness who does not hold on to something of the nursery.” I think that’s a wonderful quote, I think that’s just a wonderful… He said that, “If you really do lose all sense of that, you will never really achieve genius and greatness,” and I think that’s true.

Brett McKay: So we’ve been talking about the philosophical life lessons from The Twilight Zone, but as you said at the beginning, the show also has a creepiness factor that can be enjoyed in and of itself. So with Halloween coming up, what do you think are the scariest Twilight Zone episodes.

Mark Dawidziak: Well, what scares you is an extraordinary… I’ll ask you the same question, because what scared you is one of the most individual of responses anybody can have. I think this is like a Rorschach test, what’s the scariest episode of the Twilight Zone? For me, it comes down to two, the two episodes that I found the scariest, and I would not put these among the very, very, very best Twilight Zone episodes. If I was making a list of the very, very best I would not put these, but I would put them at the top list of the scariest. One is 22, about the performer in the hospital and she falls asleep and she dreams every night that she’s following a nurse down into the elevator, down to the basement. And there is a room that says, “22,” and it is the morgue. And the creepy nurse comes out and says, “Room for one more,” and she goes off screaming. And she finally is declared well, and she goes to catch a plane at the airport, and the flight number is 22, and the boarding attendant is the nurse, the creepy nurse. And as she comes up with her ticket, the creepy woman says, “Room for one more,” and she goes screaming off, and it’s what saves her because the plane bursts into flames on takeoff. I thought that was an incredibly scary episode.

I did at 10 years old, but I still find it pretty unnerving. The other is the Ring-a-Ding Girl, which is an odd one to say, but again, that one also has a plane crash in it. And I’m not afraid of flying. I’ve flown my entire life, I’m never feared flying, but I think that has an unnerving quality ’cause it’s about an actress, a successful actress, a star who is flying to a next job, she’s coming from Europe and their fan club has sent her a ring, a very… A ring with a large stone and in the stone, she can see people from her hometown pleading for her to come home. And the next thing we see that she’s home, and she decides to put on a concert at the local high school auditorium where she had first appeared, and a lot of people are upset about this because there’s a picnic there. There’s the annual picnic, and she goes ahead with the concert, and a plane crashes into where the picnic was, and countless lives have been saved because of her promising to do this concert at the high school and you later find out she was on the plane. So it’s got that wonderful twist ending, it’s got that, “What did we just see” quality to it. But I think there’s just something very, very creepy about that episode too that always got to me. So, those are mine. What are yours?

Brett McKay: Okay, so two have something in common. The first two are the Living Doll with Talky Tina.

Mark Dawidziak: Sure.

Brett McKay: It’s creepy. And then similar to that is The Dummy. Also terrified. I think that’s a creepy thing, inanimate objects becoming alive. Creepy. And then the other one, I would say, It’s a Good Life, with the kid who can think people dead, basically.

Mark Dawidziak: In the corn field.

Brett McKay: Right. So in the corn field. Yeah, right.

Mark Dawidziak: Well, those are all good choices, and again, I think it always goes back. You end up telling us a lot more about yourself than you do the Twilight Zone when you answer that question.

Brett McKay: So this is a good episode. So if you’re looking for a scare for Halloween, 22, Ring-a-Ding Girl, The Living Doll, The Dummy and It’s a Good Life are great ones to creep you out. I’m curious, so those are the things… Your scariest episodes. What are you… For someone who’s never watched The Twilight Zone before, what three episodes would you recommend starting with?

Mark Dawidziak: I think to this day, if you look at The Twilight Zone there are some episodes which had not dated well, but there are some episodes which actually have grown in resonance, and I think the one episode that has probably grown more in resonance than any other is The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street. First season episode about a idyllic suburban street, Maple Street, where the neighbors all know each other and all know each other’s kids and life is good on Maple Street. And on a beautiful summer evening, just as people are getting ready to fire up the barbecues and the ice cream truck is going down the street, something flies overhead, and then nothing works on Maple Street. It doesn’t matter whether it’s run by gasoline or electricity or whatever. The phones don’t work, the cars don’t work, the lights don’t work. And they start to wonder, what was it? Whatever was it a meteor? What was it? And as a teenager, a young kid says that, “This is how it happens in the stories.” “What stories?” They send ahead a family that looks like us. That what went overhead was a flying saucer, and that maybe one of the families that live on the street are not who they say they are.

So everybody starts to look at each other with suspicion and doubt, and all these people who were the best of neighbors just a little while ago, now are sort of looking at each other with a new way. Maybe these people are not… Now, obviously, Rod Serling was writing about the 1950s and the era… There was a period we had just come through, the McCarthy era, the Red Scare, when people started to look at their neighbors as… There was a communist hiding in everybody’s closet and under everybody’s bed and maybe they were the family next door, and Rod was clearly writing about the price that we would pay as a nation if we went down this path of fearing and distrusting our neighbors and our fellow citizens. Well, that message has just gotten bigger and bigger as we’ve become more and more divided as a nation. It’s become a cliche to say we are more divided now, than any time since the Civil War. I don’t know that that’s true. There have been many times where we’ve been very divided, people don’t really know American history as well as they should, especially the people who espouse it, but it is clear we are at a point where the message of that story is very, very profound. Because what Rod was basically saying was… What Lincoln tried to tell us, which is that, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”

And Rod added to that, “If we do not find a way to talk to each other, to have a discussion, real discussion, without mistrust and fear and paranoia of creeping into it, if we do not find a way to get around that we ain’t gonna make it folks.” At the end… Rod’s narration comes in at the end where he says that, “Destruction does not always come with bombs,” that there are other weapons. “There are weapons such as fear and mistrust, and that is going to be our undoing,” he says. So I think that that would be number one on my list of episodes that people should watch, if they really wanna know what the Twilight Zone could do at its finest. With that, I would add an episode called The Obsolete Man, which also stars Burgess Meredith, and also to me is a much better episode than Time Enough At Last, because I think the most heroic character in The Twilight Zone is the character played by Burgess Meredith in The Obsolete Man. He plays Romney Wordsworth, a librarian, Dickensian name Wordsworth. Serling is obviously trying to make a comment with this character’s name. The story is set in a futuristic society, and the books have become banned, the written word has become banned, and the only thing that is allowed is what is prescribed by the state, and Fritz Weaver plays the authoritarian symbol of the state.

And Romney Wordsworth has been declared obsolete. He is a librarian. He does not deny his love of the written word and the books, and he proudly states that he is a librarian and since there are no more books, hence no more libraries, there is no need for Romney Wordsworth, and he is declared by the state to be obsolete, and he can choose the method of his execution. So he asked for a bomb to be placed in his apartment to go off at a certain time, and he invites the Fritz Weaver character to his apartment, and he locks him in, and his death is going to be televised. And we get to see how Romney Wordsworth greets death and how the representative of the state greets death. And it’s an amazing episode, the lesson which Serling says later that, “Any civilization, any society that does not value the individual is obsolete, that state is obsolete.” So there’s a wonderful message about the worth of the individual, the worth of reading, the worth… It’s almost the opposite of Time Enough At Last, because this celebrates the importance of the written word. So I love The Obsolete Man, that’s one of my all-time favorite episodes, Monsters Are Due on Maple Street. And with that, I would probably add Walking Distance as… Probably if I was gonna say three episodes that everybody should watch, those would top my three.

Brett McKay: Okay, those are good ones. Well, Mark, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Mark Dawidziak: Well, I have a website, which is markdawidziak.com, I have a Facebook page, I’m always ready to interact with Twilight Zone fans. I’m one of the easiest people to find online and otherwise, so I always welcome that, the book is available through Amazon.com, it’s been there, and hopefully this will increase a little… Interest will increase a little bit because 2024 will mark the Serling Centennial, and I’m on the board of the Rod Serling Memorial Foundation in Binghamton, New York. And one of the things we are trying to do, and hopefully we’ll do either next year, but certainly, hopefully in time for the Centennial year, is get a statue of Rod erected in Recreation Park in Binghamton. Brett and I would just strongly recommend any Twilight Zone fan if you have not been to Binghamton, it’s a wonderful pilgrimage, and Recreation Park is sort of the heart of the whole thing, and Recreation Park, by the way, still has a carousel and the carousel… You can ride the carousel for free as many times as you want, and around the top of the carousel are panels, paintings, and each one depicts a scene from The Twilight Zone and they were built by a very wonderful artist named Cortland Hall.

And so there’s a bandstand and in the middle of the bandstand, there’s a gold disc which has been planted in the middle of the bandstand, and all it says is, “Rod Serling, Walking Distance.” So get to the bandstand and get to the carousel because it is your own way of experiencing Walking Distance.

Brett McKay: Mark Dawidziak. Thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Mark Dawidziak: No, my pleasure.

Brett McKay: My guest here is Mark Dawidziak, he’s the author of The book, Everything I Need to Know I Learned in the Twilight Zone. It’s available on Amazon.com, you can find more information about his work at his website, markdawidziak.com. Also check out our shows notes at aom.is/twilightzone where you can find links to resources and we’ll delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AoM Podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles written over the years about pretty much anything you can think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad free episodes of the AoM Podcast, you can do so in Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code “MANLINESS” at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and you can start enjoying ad free episodes of the AoM Podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you’d take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Spotify, helps out a lot. If you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to AoM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.