If you were going to be stranded somewhere in the wild or were facing an impending apocalypse, and could only outfit yourself with one implement, you would be wise to choose the axe. Part tool, part weapon, it’s no mystery as to why men have felt a primal attraction towards axes for thousands of years. It’s an allure that manifests itself beginning at a young age.

When I was three years old I remember watching Disney’s Paul Bunyan and being completely captivated by the giant lumberjack and his mighty ax that could fell entire forests in one swing. Inspired by this gigantic lumberjack, I immediately grabbed the most ax-like thing in the living room — the fireplace shovel — and headed outside to chop down the most forest-like thing in my backyard — my mom’s newly planted tulips. I rested my elbow on the knob of my mighty fireplace shovel-ax and surveyed my work with satisfaction, just like old Paul Bunyan did in the cartoon. I had done such a good job that the sight even brought my mother to tears. For some reason, though, she gave me a spanking and sent me to my room.

My love affair with the ax continued throughout my boyhood. When I was a Boy Scout I did whatever I could to get my hands on an ax so I could fell or split wood. Whenever I did service projects that involved cleaning up yards or property, you bet there was an ax in my hand. Today, I love to split wood when I get a chance and enjoy bucking logs with my trusty American felling ax.

While I’ve certainly enjoyed using axes for most of my life, I’ve never really known much about them except for what I picked up while earning my Totin’ Chip in Boy Scouts. So I decided to learn all I could and put together a series on this quintessential tool and symbol of masculinity. Today we’ll offer an overview on the history of the ax and its construction. Then we’ll cover how to choose an ax for yourself and how to safely and effectively use it to chop wood.

A Brief History of the Ax

The ax is one of humanity’s oldest tools, and arguably its greatest and most versatile. Archaeologists estimate that our early ancestors were using simple chipped stone wedges as hand axes over 1.5 million years ago. Around 6,000 BC, Mesolithic humans started fastening their stone wedges to a handle — often made from antler or bone — with rawhide lashings. Adding a lever increased the cutting power of the early ax and turned it into a jack-of-all-trades tool. Our human ancestors used these implements to dig up roots, cut wood, butcher animals, and even kill each other in battles.

By 4,000 BC, humans were grinding edges on their stones for more efficient cutting. In the late Neolithic era, the first metal ax heads were hewn from copper or copper mixed with arsenic. While these copper heads were flatter than the stone variety, they were still fastened, or hafted, to the handle with birch tar and leather lashings.

As advances in metallurgy were made, the ax continued to evolve. While axes have always doubled as both weapon and tool, in the Bronze Age, blacksmiths began creating versions especially for war. For example, double-bitted (meaning it has blades on both sides of the head) battle-axes have been found in Crete that date back to 2,000 BC, and the Egyptians wielded a unique battlefield weapon called the Epsilon Ax. One of the more significant and field-expedient changes made to the ax’s design during this time was how the head was hafted to the handle. Artisans and blacksmiths designed a metal ax head that could be inserted snugly into the handle, rather than tied on, thus creating a stronger, more secure weapon.

While different trades developed different axes for their various needs, and warriors refined their weapons for better lethality, the design of woodcutting axes hit a slump from about medieval times until the late Renaissance. During this period, Europeans had the “trade ax” that they used for pretty much anything and everything — felling trees, splitting wood, butchering animals, etc. But the trade ax wasn’t very efficient in the woodcutting department. It would take Europeans migrating to North America for the ax to make another leap forward.

The first European settlers in America needed land for farming. Standing in the way of their crops, however, were dense forests that covered the virgin landscape. The trade ax that settlers had brought with them just wasn’t going to cut it (see what I did there?), so these early pioneers started experimenting with and modifying its head to create a more efficient felling tool. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, different locations in America began producing various types of heads for felling axes. While the designs differed from state to state (at one point in the 19th century there were more than 300 different ax head patterns being sold), what they all had in common was that they were shorter and broader than their European progenitors. This stouter head was much more efficient for felling trees and became characteristic of what came to be known as the American ax — a tool that now serves as the Platonic ideal of axes the world over.

With this new ax head design, farmers and pioneers were able to clear entire forests in a (relatively) short amount of time. In areas that required substantial tree felling, the double-bitted ax rose in popularity. As noted above, double-bitted battle-axes had been around since 2,000 BC, but it wasn’t until the 19th century in Pennsylvania that the tool was used as a felling device. Having two cutting edges on a single ax head made for much more productive woodsmen. While some kept both edges sharp and began the day cutting with one edge and then flipping to the other once the first dulled, others used the two bits for different purposes. One edge was made sharp for felling, while the other was kept blunt and rounded for limbing.

Farmers were reluctant to adopt the double-bitted ax, though, primarily out of safety concerns. Because its head had cutting edges on both ends, the chances of injuring oneself or another significantly increased. In many areas, the tool was called a “backstabber” due to people literally stabbing themselves while carrying it over their shoulder. Consequently, the double-bitted ax largely remained in the realm of the professional lumberjack.

Axes remained vital tools for loggers and all manner of rural residents alike up through the beginning of the 20th century. It was then that the portable chainsaw was developed, which slowly replaced the trusty ax for most woodcutting jobs. When Dudley Cook published The Ax Book in 1999, he could confidently say: “If you want to be fashionable, buy a chainsaw. They are in.” His argument for the ax had a kind of wistful, quixotic tone, as chainsaws were then seen as status symbols for the suburban set, and axes had largely been forgotten.

A decade and a half later, things have swung the other way; because of the recent revival in all things “heritage” related, axes are now very much “in.” But they tend to be bought by urban and suburban dwellers more as decorative and conversation pieces than tools. The utilitarian ax still has a place in the modern man’s shed, however, and does in fact offer some advantages over the chainsaw.

Advantages of the Ax

Chainsaws vs. axes isn’t an either/or question; each tool works best for different tasks, and most folks who do a good amount of woodcutting employ both. But discussing the advantages of axes over chainsaws is an effective way to highlight exactly what an ax is good for and how it can be used.

When it comes to felling and bucking large trees, the chainsaw will get the job done much faster and with less effort. Cutting with a chainsaw also wastes less wood than chopping with an axe. But for lighter work, like limbing small firewood with a 4” diameter or less — using an axe can be just as fast. Even for slightly larger woodcutting, you might consider using an axe rather than a chainsaw for these reasons:

- Quiet. Chopping trees in the woods can be a meditative activity; but the buzz of a chainsaw kills that calm. Chainsaws are so loud you’ll need to wear earmuffs to protect your hearing.

- Safer. Axes can cause injuries to be sure, but they don’t run the danger of kickback and pinching like chainsaws do, and don’t chew up your body like a fast-rotating saw.

- Less maintenance. A chainsaw requires a good amount of upkeep. You’ve got to keep it filled with fresh, ethanol-free gas, apply two different kinds of oil, clean the air filter, tighten the chain, and so on and so forth. If it breaks and you can’t fix it, you’ll have to bring it in for service. With an ax, all you’ve got to do is keep it sharp.

- Less accessories. In addition to the gas and oil you’ll need for your chainsaw, you’ll also have to get special safety equipment like Kevlar chaps and earmuffs. With an ax, you’ll just need a sharpening stone/files and eye protection.

- Portable. Chainsaws are bulky and require toting fuel along with them. Axes weigh two-thirds less, and are thus your best choice for carrying along deep into the woods.

- Exercise. Chainsaws save you on exertion, but sometimes exertion is exactly what you’re looking for. Chopping wood gives you a damn good workout, which is why Henry Ford celebrated it as a task that warms you twice.

There’s a longer learning curve in using an ax (properly) than a chainsaw, and the latter can cut things quicker, but when you add in the prep of getting a chainsaw ready and the maintenance needed when your task is done, the time factor starts evening out. The simplicity of the ax — the fact you can grab it and go anywhere — is a beautiful thing. So by all means break out the chainsaw when you really need it for big woodcutting jobs, but keep the axe in mind as a viable option for your smaller tasks.

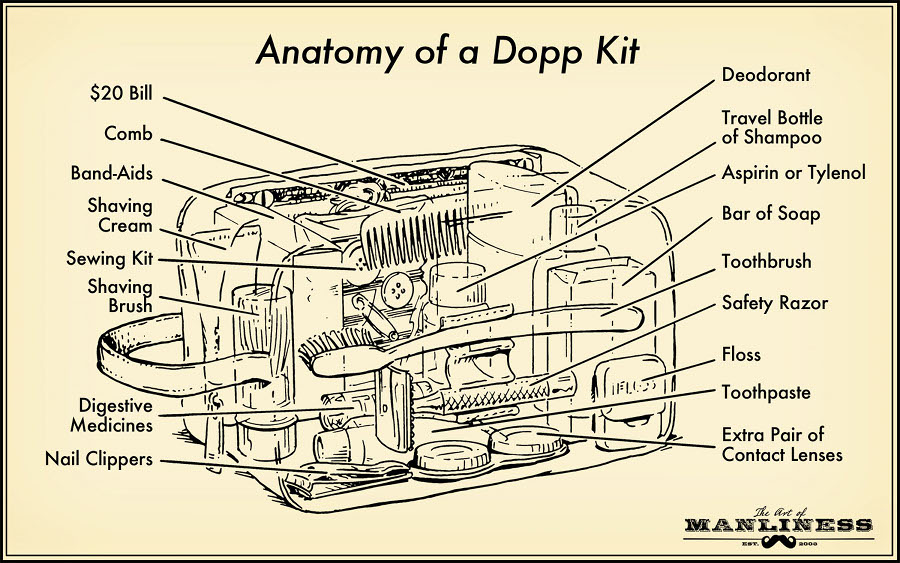

Anatomy of a Single-Bitted Ax

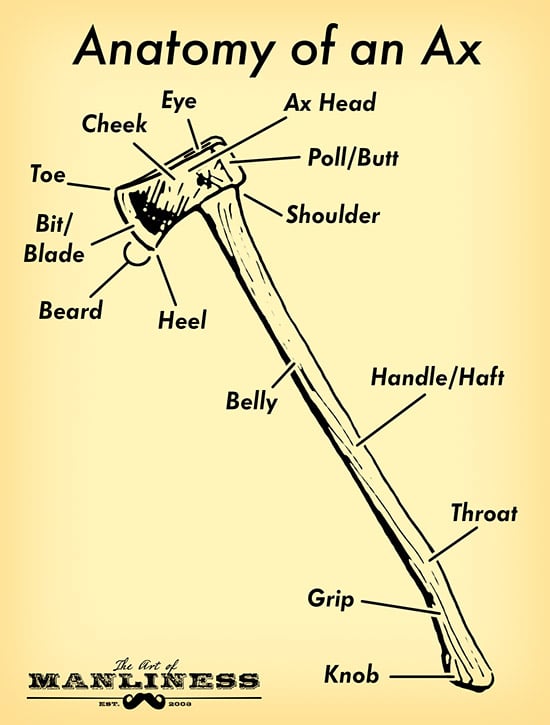

To know your way around an ax, familiarize yourself with its parts and the terminology used to describe them:

- Ax Head: Typically has two ends — the bit or blade on one side, and the poll or butt on the other

- Bit: The cutting portion of the ax head; also known as the blade or the edge

- Poll: The blunt part of the ax head that aids in balance and control; also known as back, butt, or heel

- Toe: Upper corner of the bit where the cutting edge begins

- Heel: Bottom corner of bit

- Cheek: The side of the axe head

- Beard: Part of the bit that descends below the rest of the axe head

- Handle/Haft: Usually made of springy hardwoods like hickory but can be made with durable synthetic materials

- Shoulder: Where the head mounts onto the haft

- Belly: Longest part of haft; often made with slight bow

- Throat: Where haft curves into the short grip

- Knob: End of haft

- Eye: Hole where the haft is mounted

Types of Axes

There are many types of axes out there — felling axes, splitting axes, carpenter’s axes, and so on — but they generally break down into two main categories:

Single-Bitted Ax

The single-bitted ax is the most common felling ax out there. It’s likely what you imagine when you hear the word “ax.” The head of a single bit has two ends; on one you have the cutting bit (blade), and on the other the poll (butt). While the poll of an ax looks like a hammer, you should never hammer with it. You’ll just damage the ax head if you do.

Most single-bitted axes have a nice, gently curving handle that ends with a flourish curve at the knob. This curved design didn’t come into wide use until the middle of the 19th century. Before that time, the handles were straight. No one knows why the curved handle came into favor over the straight, because straight handles actually wobble less and are more accurate when swinging. One theory is that the curve was thought to increase springiness and whip, thus allowing the user to generate more force, but that’s up for debate. The lumberjacks of the 19th and 20th centuries swore by the straight handles on their double-bitted axes, and saw no reason to change. At any rate, some single bit manufacturers have gone to a straight handle these days, while many have stuck with the curved variety. The persistence of curved handles perhaps simply comes down to the fact that what it lacks in efficiency, it makes up for in good looks.

Single-bitted axes are great all-around woodcutting tools. You can fell medium-sized trees, buck them, and even limb them. While not ideal, in a pinch you could also use a single-bitted ax to split wood, though a true splitting maul is better suited for the job.

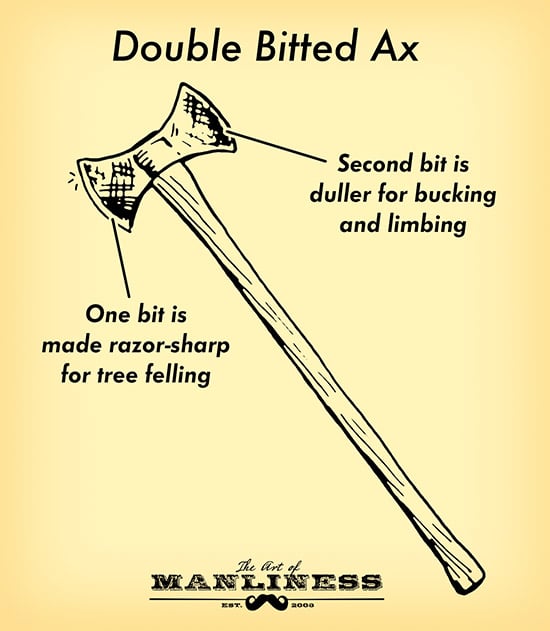

Double-Bitted Ax

Unlike the single-bitted ax that has a hammer-like poll on one end of the ax head, the double-bitted ax has two cutting edges. Typically, one edge is sharpened for fast, efficient, chopping, while the other is left a bit duller for limbing or chewing through tough knots.

Unlike the single-bitted ax with its pretty S-curve handle, a double-bitted ax requires a straight handle that allows the woodsman to swing it in either direction. The handles are also longer and thinner than those on single-bitted axes, allowing the swinger to generate more speed and power. While the longer handle would in theory make the ax more cumbersome, and force the user to trade accuracy for power, the double bit is in fact more accurate than its counterpart. The fact that both ends of the head are of equal length and weight gives the ax a greater balance and reduces wobbling on the swing. Together, these factors make the double bit the most effective ax, and explain why it was the go-to tool for professional lumberjacks.

While double-bitted axes are unmatchable chopping machines, and certainly look freaking awesome, if you don’t plan on felling copious amounts of trees there’s no need to have one, unless you just want it around for a decorative piece or perhaps to use as a battle-ax in our coming Mad Max dystopian future.

For most men, the single-bitted ax is the right choice. But which one to get? There are many factors to consider such as weight, size, handle type, etc., all of which we’ll cover in the next installment. Until then, keep your axes sharp, and stay manly.

Read the Series

History, Types, and Anatomy of the Ax

How to Choose the Right Ax for You

How to Use an Ax Safely and Effectively

_____________________

Sources:

Illustrations by Ted Slampyak