Editor’s note: This is a guest article from TJ Cosgrove.

For most people, the humble pencil is a writing utensil that was once familiar, but is now largely absent from their everyday life.

When you were a kid, you used a #2 pencil to fill out the answer sheet bubbles on standardized tests. Maybe you kept using the mechanical kind to do math in college. But as an adult, unless you’re a craftsman making marks on lumber or drywall, you may not use pencils at all, having dropped them in favor of pens.

I don’t entirely blame you. A yellow Ticonderoga or a plastic mechanical pencil offered very little in terms of real pleasure. With a scratchy tip, or lead that constantly snapped off, pens seemed to offer a superior, smoother, more indelible writing experience.

But there’s more to pencils than the kind you used as a kid. Upgrades in the pencil’s core, and in the wood which surrounds it, can make a big difference in how satisfying it is to write with. So if you don’t think pencils are for you, but have never used anything but the drugstore variety, you just may not have tried the right one yet.

Today I’ll unpack the surprisingly nuanced world of these underappreciated writing utensils, explaining their various features/qualities and offering some suggestions for branching out from the kind you grew up with.

Why Use a Pencil?

When you try out writing with a nicer pencil, you’ll likely be quite surprised by how differently — and more winningly — it writes than you’re expecting.

A quality pencil, in fact, can provide a tactile writing experience that not only rivals that of a pen, but in many cases surpasses it. There’s just something that feels very connected when laying down brainwaves in streaks of carbon on wafers of cellulose.

While the friction of a quality pencil on paper is much smoother than you might imagine, there’s also something about the way it leaves its essence behind — becoming smaller as you use it, extinguishing itself as it brings your words and scribbles to life. There’s something too about a pencil’s natural construction — a wood case surrounding a core of graphite and clay — and about the fact you have to continually sharpen it to keep it keen; this repeated whittling-in-miniature, complete with little curls of wood or bits of sawdust, offers a tangible pleasure . . . and an apt metaphor for life.

Beyond the more ineffable pleasures of the pencil, are its eminently utilitarian qualities. Unassumingly simple, pencils are steadfast and dependable tools: there’s no battery to charge or signal to lose; there’s no ink that can leak or unexpectedly run out. Pencils work in any language, on almost every medium, and in wind, under water (at least if you have the right writing surface!), or in zero gravity. And of course with its double-sided design — a point on one end and an eraser on the other — they can be used for both creation, and destruction.

Both functional and aesthetically pleasing, once you start incorporating quality pencils into your life, you may find it’s your pens that increasingly get left in the desk drawer.

The Qualities of a Pencil

Grade

It is a common myth that the core of pencils used to be made from lead. The misnomer can be traced to the 17th century, when a particularly violent storm felled a large tree in England and its roots unearthed a dark metallic substance — raw graphite. Farmers started using it to mark their sheep, christening it “plumbago” or “black lead.” The name, catchy though erroneous, stuck. (Interestingly though, in years gone by it was not impossible to get lead poisoning from chewing your pencil, as they were often lacquered with lead-based paint.)

The core of a pencil has actually long been made of a combination of clay and graphite, and the ratio of these two components gives the pencil its “grade.”

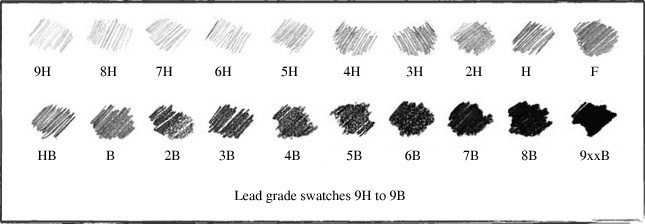

Pencils are categorized primarily through this grading, which is measured by two major scales: the European HB scale and the American # number scale.

The European system was originally created in 1789 by Bohemian pencil titan Josef Hardtmuth and measures Hardness against Blackness. HB is the center of the scale: equal parts Hardness (clay) and Blackness (graphite).

The HB grading scale. Image Source

As we move up or down the scale, additional clay makes the pencils physically harder and their marks lighter, while additional graphite makes the pencil softer and much darker on the page.

The American system (coined by 18th century French inventor Nicolas-Jacques Conte) uses numbers, often paired with a pound sign. #2 is the middle grading and the closest approximate to HB. #1 has more graphite, and is consequently darker and softer, while a #3 has more clay and is lighter and harder.

The biggest problem with grading is that users, manufacturers, and even countries do not agree on any kind of standardized grading system. An HB in England is not necessarily the same as an HB in Germany. Don’t even try to use an HB if your teacher asks you to use a #2.

Most readers will have an idea of what a #2/HB pencil feels like. It’s the standard and most common grade. You probably used them to fill in tests or scribble stick people in the margins of your school books. If you’ve ever been to IKEA, you have seen a half pint HB.

As it goes, American and Japanese pencils tend to err on the darker side, while German and other European pencils tend to sit a little lighter on the grading scale. There are of course some exceptions to the rule and a few total outliers who refuse to use a scale at all (looking at you Blackwing . . .).

The most important thing when picking a pencil grade is to ensure it works for you. Too hard and it will feel like writing with a fork tang, too soft and you won’t get half a sentence before you need to sharpen again.

If in doubt, I suggest you go softer and darker. It’s easier on the hand and has better legibility. Try a 2B against your normal #2 and tell me it ain’t nicer to write with.

Lacquer

The lacquer on a pencil is the protective covering for the wood. It stops the wooden barrel from becoming stained with the daily wear and tear of desktop life. It also provides a smooth and consistent texture for the hand to grip.

If I ask you to close your eyes and imagine a pencil, almost everyone will think of a yellow pencil. That’s because it’s the most commonly used color of lacquer, but this was not always true. Until the 1890s, pencils were typically clear lacquered or unfinished, as this allowed consumers to see the high-quality wood that went in to their high-quality writing implement. Poor quality wood was often hidden behind dark maroon, black, or green lacquers.

After the discovery of a new vein of high-quality graphite in Siberia, close to the Chinese border, H&C Hardtmuth started manufacturing pencils from this new source. To promote their new luxury line of “Koh I Noor” pencils, which utilized this superior “oriental” graphite, they chose to lacquer the pencils yellow. The color yellow, while commonplace now, had connotations of superlative quality and royalty associated with the Chinese Yellow Emperor.

The marketing campaign worked, the Koh I Noor pencils sold so well they renamed the company Koh I Noor Hardtmuth (still going today in the Czech Republic), and yellow became the de facto color for woodcase pencils both in the US and most of Europe.

Selecting a pencil with a quality finish is important, as cheap lacquer (which is found on cheap pencils) is unpleasant to the touch and can chip or flake off. Or you may find that you prefer an unlacquered pencil; it does get dirty quickly, but that may be an acceptable trade-off for enjoying the raw wood feel.

Point Retention

Point retention is a measure of how long your pencil comfortably writes before becoming dull, unwieldy, and unpleasant. There is a direct correlation between the grade of pencil you choose and the length of time your point will be viable. Softer pencil tips will round off and widen much faster than their harder brethren.

Point retention is important if you are a long form writer, and don’t want your sessions constantly interrupted by trips to the trash can.

Either choose a harder grade, or take the Steinbeck approach:

Sharpen 24 identical black pencils and place them point up in one of two identical wooden boxes. Then pick up the first pencil and begin writing. When the point dulls (typically after four or five lines) place it in the second box, point down. Continue until all the pencils have been used and migrated to the second box.

Sharpen all pencils again, return to the first box, and repeat as necessary.

Some people can and will write with a nubbin of graphite that is about as sharp as an eggplant. My fiancée, for example, will actively snap a freshly sharpened point in half, then scribble it to get a rounded and inoffensive stylus with which to write. Personally, I prefer something with a little more acuteness in the angularity.

Smudge

Smudge is caused when excess graphite not embedded into the cellulose fibers of the paper is brushed and smeared across it. While actually a feature of pencils when utilized for artistic pursuits, it is unsightly, annoying, and generally frowned upon by writers.

This issue is especially salient for lefties, as the normal hand posture adopted when writing left handed will inevitably lead to significant smudging, leaving a shiny graphite tattoo on the leading edge of their little finger and palm. Best advice: use a harder grade with less graphite or learn to embrace the sheen.

Erasability

Erasability refers to how well a pencil’s mark may be eradicated by way of an eraser (or rubber as we call them here in the UK). The importance of erasability is influenced by the way you write. If you are a perfectionist, then the ability to erase and remark paper is fundamentally important; you can hide your mistakes with the revisionist touch of an eraser. If, like me, you like to show your work, then erasers are an oft-ignored part of your stationery kit. I tend to put a line through errors and carry on, with my mistakes sometimes providing more illumination in retrospect than the answers I eventually came to.

If erasability is important to you, then use a lighter pencil. More clay and less graphite mean a lighter mark which is easier to erase.

Or play with the eraser you use. As with many things, everyone has an opinion on what is best when it comes to rubbers. Cheap erasers tend to produce a fine sprinkling of rubber “dust.” Higher quality ones, at least in my experience, create “curls.” Generally, a separate, off-the-pencil eraser is better quality, and provides a larger surface area; high quality Japanese ones, which are formulated to remove lots of graphite and leave clean pages, come well-recommended. Pencil-top erasers are really put there as an emergency measure, as anyone can attest to when they are almost entirely eroded in rubbing away one mistaken sentence.

If you find yourself in a real emergency, and have no eraser left atop your pencil at all, know that in days of yore, people used a rolled-up piece of bread to clean up their mistakes — which still works in a pinch!

Sharpening Your Pencil

Sharpening can be done in all manner of ways, ranging from rotary desk mounted contraptions to the humble pocket knife.

The more “automated” your sharpener, the less control you have over the shape/size of the resulting point. An electric or hand-crank model will tend to produce a generally inoffensive and practical point, but far better results can be achieved with a hand sharpener or knife.

There are a number of excellent hand sharpeners at a variety of price points. German company KUM makes some excellent higher end ones, including the flagship KUM Masterpiece, which can create long points to rival even the steadiest knife sharpen. Cheap sharpeners can be just fine, and the Indian Apsara long point is a favorite of mine that costs literal pennies and can be bought in bulk directly from India.

If the sharpener leaves a rough finish on the pencil, or the wooden curls are short and flaky, its blade might be blunt. Generally, sharpeners are cheap enough that once this happens, it’s time to move on and replace it.

Sharpening a pencil by hand with a knife will give you the most control of your point, but as this is a personal and nuanced subject, we’ll cover it in a separate piece.

Suggestions for Branching Out From Your Everyday Pencil

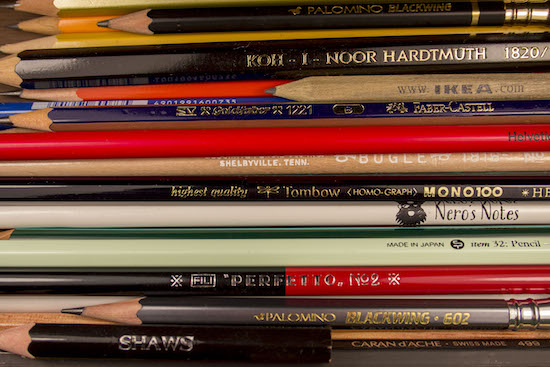

If you’ve only ever used the basic pencils of your schooldays, you really owe it to yourself to branch out and explore other kinds. While quality pencils are a little more expensive than the everyday variety, the upgraded price creates a significantly upgraded writing experience.

As with many things, your mileage may vary and personal preference has an enormous impact on what you will ultimately use and enjoy. I thus recommend trying everything and anything you can get your hands on — only then will you know what best suits you. Below you’ll find some of my suggestions, based on where in the world you live.

If you are based in the continental United States, it’s easy and affordable to start experimenting with pencils beyond your normal scope of recognition. There is a whole suite of American companies turning out great writing implements including General Pencil Co, Musgrave, and Palomino.

Most Americans will be familiar with the yellow Dixon Ticonderoga #2, but give the Black Ticonderoga a go for the simple pleasure of mixing up your lacquer colors. For a real step up in quality (without a big jump in price), try the Golden Bear by Palomino; they’re still cheap ($2.95 for 12) but infinitely better.

For a natural unlacquered pencil, try the General’s Cedar Pointe.

If you want to get fancy, then get a pack of Palomino Blackwing 602s; encased in fragrant cedar, with a distinct and enjoyable dark core that lives up to its “Half the pressure, twice the speed” tagline, this is often the “gateway” pencil that changes people’s minds about pencils.

If you’re in Europe, there are plenty of local stationery giants like Staedtler, Koh I Noor, and Faber Castell to peruse.

Most will be familiar with the distinctive yellow and black striped Staedtler Noris HB (the Ticonderoga of Europe) but have a go at the blue and black Staedtler Mars Lumograph in 2B.

For something historic, give the original yellow pencil a go: the Koh I Noor 1500 is available in 20 different grades and remains mostly unchanged since it was introduced 120 years ago.

For something a little different, try the Caran d’Ache Bicolour, a double-ended red and blue pencil often used for marking or amending documents.

Asia is not without its own cabal of manufacturers and brands. Japanese pencils, inspired by the calligraphic nature of kanji, are typically dark and smooth. Tombow and Mitsubishi make some wonderful pencils like the Tombow Mono 100 or Mitsubishi Uni-Star.

Once you start trying different pencils, you may fall down a rabbit hole with them, and really start collecting them in earnest. Happily, pencils are such a constant across the world, that you can go to almost any country and find a shop stocking notebooks and pencils to add to your collection. In the Czech Republic, I trekked from street to street, collecting every kind of Koh I Noor pencil I could find (there is even a pencil shop in Prague Zoo). In China, I haggled for handfuls of Chinese pencils with a market vendor in Xi’an. There has not been a city yet that I haven’t been able to satisfy my pencil cravings in, and finding them always leads me on a new adventure.

But if you’ve rarely picked up a pencil since childhood, you don’t have to travel the globe to experiment; just try branching out a little where you are, and you may find your new favorite tool for conveying your thoughts from cerebrum to cellulose.

___________________________________________________

TJ Cosgrove is a pencil pushing filmmaker. He runs Wood & Graphite the #2 pencil-based video channel on the internet. He also talks about the past and the present in an anachronistic podcast called 1857. He likes hard science fiction novels, pencils and American beer, though not necessarily in that order.