Everyone gets old.

But not everyone experiences old age the same way. Some folks spend the last few decades of their life sick, sad, and stagnating, while others stay sharp and find great satisfaction in the twilight years of life.

My guest today is a neuroscientist who has dug into the research on what individuals can do to increase their chances of achieving the latter outcome instead of the former.

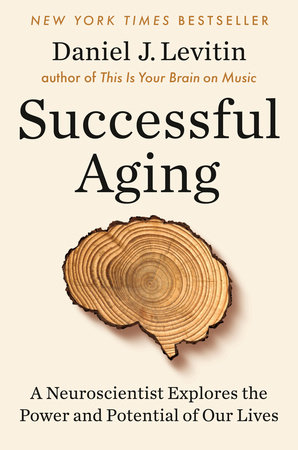

His name Daniel Levitin and today we discuss his latest book Successful Aging: A Neuroscientist Explores the Power and Potential of Our Lives. We begin our conversation discussing the societal narratives we have about old age that don’t always hold true. We then dig into the fact that while the brain slows in some ways with age, it gets sharper in other ways. Daniel shares the personality trait that’s the biggest predictor of a successful elderhood, and the recognizable-yet-surprising reason the idea that memory declines with age is overblown. We also talk about what really works for preserving your memory and keeping your mind agile and keen, and no, it’s not doing puzzles and brain games. We end our show discussing the question of whether people get happier or sadder as they age.

Show Highlights

- What are some of our culture’s myths and biases about aging?

- How the elderly get marginalized in our society

- What’s going on in our brain as we get to our 40s, 50s, and 60s

- Why intelligence improves with age

- The importance of conscientiousness as a trait for aging successfully

- Why you should focus on learning and doing new things as you age

- Do we really become more forgetful as we get older?

- What can we proactively do to improve our memory? Are brain games bunk?

- How and when we attribute our maladies to age rather than randomness

- Why physical movement is so crucial for physical and mental health

- The undeniable power of strong social connections

- Nature’s restorative powers

- Why older adults are actually happier than younger people

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Organized Mind by Daniel Levitin

- This Is Your Brain on Music by Daniel Levitin

- The Journey to the Second Half of Life

- AoM series on the seasons of a man’s life

- How to Get a Memory Like a Steel Trap

- What Can a Man Learn From His Grandparents?

- Why Your Kids Need Their Grandparents

- The Unexpected Upsides of Being a Late Bloomer

- Love Is All You Need

- How and Why to Become a Lifelong Learner

- Laura Carstensen

- Take the One-Month “Do Something New Every Day” Challenge

- The Art of Anticipation

- Wish You Had More Time? What You Really Want Is More Memories

- Keep Moving

- Take the Simple Test That Can Predict Your Mortality

- How to Develop Your Nature Instinct

- The 5 Switches of Manliness: Nature

- How Navigation Makes Us Human

Connect With Daniel

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Saxx Underwear. Game changing underwear, with men’s anatomy in mind. Visit saxxunderwear.com/aom and get 10% off plus FREE shipping.

Capterra. The leading free online resource for finding small business software. With over 700 specific categories of software, you’re guaranteed to find what’s right for your business. Go to capterra.com/manly to try it out for free.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay:

Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Everyone gets old, but not everyone experiences old age in the same way. Some folks in the last few decades of their life sick, sad and stagnating, while others stay sharp and find great satisfaction in the twilight years of life. My guest today is, a neuroscientist who’s dug into the research on what individuals can do to increase their chances of achieving the latter outcome instead of the former. His name is Daniel Levitin, and today we discuss his latest book, Successful Aging: A Neuroscientist Explores the Power and Potential of Our Lives.

We begin our conversation discussing the societal narratives that we have at old age that don’t always hold true. We then did dig into the fact that while the brain slows in some ways with age, it gets sharper in other ways. Daniel shares the personality trait. That’s the biggest predictor of successful elderhood, and the recognizable yet surprising reason the idea that memory declines with age is overblown.

We also talk about what really works for preserving your memory and keeping your mind agile and keen, and know it’s not doing puzzles and brain games. We spend the rest of the show discussing the question of whether people get happier or sadder as they age. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/successful aging.

All right, Daniel Levitin. Welcome to the show.

Daniel Levitin:

Thank you Brett.

Brett McKay:

So you are a neuroscientist and a cognitive psychologist who has written books about thinking clearly. That book was The Organized Mind, fantastic book, and also how music affects our brain. And you’ve got a new book out called, Successful Aging: A Neuroscientist Explores the Power and Potential of Our Lives. So what kick started your research in writing about getting older, and how it affects the brain, and everything else about our lives.

Daniel Levitin:

Yeah, it’s maybe not an obvious transition from the other books, right? But as I’ve gotten older myself, I couldn’t help but notice that some people tend to age better than others. Why would that be? I have colleagues who are in their nineties who are still as sharp as ever. Others in their mid-sixties, who have slowed down so much, they can’t do their work. There are clearly some individual differences there. And as a neuroscientist and a cognitive scientist who studies individual differences, I find this intriguing.

I really wanted to be able to give advice to my parents, who are 85 and 87, and still doing well about how they could remain that way. And selfishly I wanted to know what I could do to stay as engaged and energetic as they are as I get older. And so I looked all around for books about this and I couldn’t find any. So as with my other books, I basically wrote the book that I wanted to read.

Brett McKay:

Yeah. And I think that’s true. One thing I’ve noticed as I’ve gotten older is you look for books as you’re in your 30s, your 40s about how do I transition to midlife? And there’s nothing really there. There’s a lot of stuff on kids or teenagers, but sometimes that latter half of life gets overlooked on providing guidance.

Daniel Levitin:

Right. And, and so, I wasn’t thinking, “Well I need to fill a hole in the library or in the bookstore,” but I wanted to read that book.

Brett McKay:

So let’s start off with misconceptions that people have about aging. Or maybe they’re not misconceptions, because as you said, there’s differences on how people age. So sometimes we see ways one person ages and think, “Well that’s just how all people age.” So what are some of the common things that we think about or associate with aging and cognitive performance and just overall vitality in life?

Daniel Levitin:

Well, we do have some biases in our culture, a kind of ageism. and the biases, the way memory works is that if you’re going into an experience with a bias, you tend to notice all of the things that confirm that. We call it confirmation bias.

So if you already think that old people are decrepit and declining, and you see a few of them, those are the ones you notice and register, and you don’t notice all the exceptions to that. And in fact, in my experience, there are more oldsters who are doing well, than are not doing well. And just to continue the thought, I feel, I’m noticing, I’m certainly not the first to notice it, but I’m noticing it more acutely that oldsters have become marginalized.

I saw it in my own life. My grandfather was forced into early retirement, as was my father. And I’m on some committees, some academic committees for hiring in Germany for the Max Planck Institute there. And Germany still has mandatory retirement at age 67. So I would call that a form of ageism. The societal narrative is that old people need to get out of the way and make room for youngsters.

And so, one misconception is that old age is a time of decline and debilitation, sadness, and irrelevance. It is for some, but for many it’s the best parts of their lives. And for those who get to interact with them.

Brett McKay:

And we’ll talk about how some of the benefits of aging that you get as you get older that you don’t have when you’re younger. And I think it’s true, that idea of this societal narrative. I’ve noticed that I feel like our ideas of what old people are, are still like, they’re stuck in like the 1920s or ’30s, right? When you look at old pictures of a grandpa who was 55, and they looked really, really old because they were probably working in the fields. Healthcare wasn’t that great. I remember this movie, there’s this woman, she was 60, and she’s a grandma, she’s wearing this brooch, and she like walked all decrepitly. But 60 because if you think of advanced in healthcare, you can be like you’re 40 when you’re 60.

Daniel Levitin:

60 is the new 40, and hey, 80 is the new 60.

Brett McKay:

Right. So that means. what has happened is our narrative hasn’t caught up to the reality of aging in the 21st century.

Daniel Levitin:

Right. I think that’s right.

Brett McKay:

So let’s talk about it. So you’re a neuroscientist. So you look at the brain and how it changes. And we all know that the brain undergoes rapid changes physiologically in childhood and then in the teenage years, it’s sort of like a rewiring. I think people tend to think, well after you’re done, after you’re 20, your brain’s kind of set in stone. What you got is what you got. But you highlight research that our brain continues to physically change as we get older. So what’s going on there as we hit our 40s, 50s, and 60s with our brain?

Daniel Levitin:

Well, so the brain is constantly rewiring itself at any age. It’s true that thinking becomes slower with every decade after 40, and parts of the brain shrink. Thinking becomes slower for a number of reasons. One is we enter a process of demyelination. Myelin is a fatty sheath that coats neurons and acts as an insulator. And by an analogy to an electrical circuit, if the insulation on the wiring in your house gets frayed or degraded, you could have sparks, and then the electricity isn’t all going to where you want it to go. Some of it’s being lost and can cause damage. And that’s what happens in brains. The myelin begins to decay. That’s some of the slowing, but not all of it. There are a number of reasons.

But the good news here is that a variety of compensatory mechanisms kick in even as the slowing occurs. Now, one form of rewiring is the ability to see patterns in the world that is improved among oldsters. And that’s true, whether it’s the social world or the perceptual world. So my view and, a growing community of people who share the view, is that we do become more intelligent in the way that we’re using the word as we age, because we’re acquiring more information, we’re having more experiences, we learned from teachers, books, friends, newspapers, interactions with the world, social encounters. And that adds to our intellect.

Brett McKay:

So it sounds like, correct me if I’m wrong, this is how I’m understanding. In some ways, yes, we slow down as we get older, but in some ways we speed up because of that accumulation of what we can, I mean we call it mental models, right? You’re able to see patterns more readily in the environment because you’ve had so much experience so you can make a decision faster just based on just recognizing a pattern as opposed to say a younger person who hasn’t had that experience. They have to spend a lot of time spinning wheels to figure out on the fly what to do.

Daniel Levitin:

Yeah. I always say if you’ve got some sort of growth and you get an xray and you want to know whether it’s cancerous or not, you want a 70-year-old radiologist, not a 30-year old radiologist. You want somebody who’s seen thousands of these things. That’s pattern matching.

Brett McKay:

Yeah. So that’s a case for keeping on older employees, or employee, maybe having them in their 60s, 70s, 80s, so they can continue to work because they can bring so much accumulated knowledge to the field.

Daniel Levitin:

They can and they also bring knowledge of social interactions and the kinds of mistakes that may have made been made before.

Brett McKay:

And that’s why, I mean you see this pattern recognition. You see that’s what judges do. And a lot of judges can continue doing their job into their 90s, and do it very well.

Daniel Levitin:

You’re right. And I had the opportunity to spend time with a federal judge, Jack Weinstein, who’s 98 years old and handles a full case load. And in fact he’s so sharp and so good at discerning patterns in behavior and in court documents that other federal judges in his district often hand him the most difficult cases. He’s that good.

And we see it in good police detectives, and FBI agents, and profilers who are able to detect patterns that elude the rest of us. And that’s based on experience.

Brett McKay:

So thinking slows in some ways when we age, but sharpens and other ways. And the brain continues to rewire itself even as we age. Why is it then that it seems like many older people struggle with adopting new technology?

Daniel Levitin:

I think older people have difficulty with new technology just because for neuro reasons and for psychological reasons, as we get older, we become a bit more conservative. I don’t mean that in a political sense, necessarily. But you could broadly characterize life the lifespan as consisting of different chunks. Where as a child you’re trying to acquire the information that will allow you to become somewhat self-sufficient to go to the bathroom yourself, to read, to entertain yourself, to make friends and choose your friends. In early, young adulthood, our 20s and 30s, we’re seeking out, maybe starting in the teen years, we’re acquiring information for a different purpose. We want to understand what we like and what we don’t like. What kind of person am I? Am I somebody who likes to do this? And so we try a lot of different things. Some of us more than others. But the time of exploration is the late teens and 20s. Then come the 40s most of us settle down a bit and work to build up our careers, possibly build up a nest egg, a family.

And by the time we hit 60 or so, we’re less interested in exploration and in finding out what things we might like. We already know what we like. We come more interested in spending our time doing the things we already know we like. And so this whole mindset means we’re less likely to try new restaurants, or want to make new friends, explore new places. That’s not a positive brain health perspective, and I argue in the book that we have to fight against that kind of complacency.

And the connection to technology is for a lot of older people, it’s just, “Why does this have to change? I liked the old system, I was used to it. Why do I have to learn this new thing?” And the icing on the cake is that with all of this as a feature of old age going back centuries, we’ve really seen a tipping point where a sea change in the rapidity of technology.

If you were 80 years old a hundred years ago, so let’s say 1920, you were seeing for the first time things like women getting the vote, automobiles, airplanes, telephones, radio, that was a lot of new technology in your lifetime. But it came along rather slowly. Now, there is new operating systems and cell phones become obsolete and the OSs they run on become obsolete. So I’m thinking about my parents who, every couple of years the landscape completely changes. That’s a very rapid, the landscape of cell phones and websites and computer stuff. That’s a very rapid change comparatively speaking.

Brett McKay:

Right? So, but some people, the older people do still manage to be open to learning new things, and not just go into the stuff they’re comfortable with. And you talk about the view in the book that the research shows our personality plays a big role in whether we age successfully. And personality is sometimes associated with temperaments, so it’s like openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness. And then was the other one?

Daniel Levitin:

Neuroticism.

Brett McKay:

Neuroticism.

Daniel Levitin:

Yeah, and extroversion.

Brett McKay:

And so what personality traits of those are associated with successful aging?

Daniel Levitin:

Well two in particular. And one of them dominates everything else, and it’s a cluster of traits that has to do with conscientiousness. It turns out that the biggest predictor of how well you’ll age, I mean apart from whether you were in a war, or got hit in the head, or things like that, the biggest predictor is conscientiousness and a cluster of traits surrounding that.

Because conscientious people go to the doctor when they’re sick. They have a doctor, they know who to call. And when the doctor gives them medication, they actually follow the instructions, and they it. They do what the doctor tells them. Conscientious people tend to not spend all their money, so they have a nest egg for when something bad goes happen. They’ve built up a retirement fund. And you’re born with a genetic predisposition towards conscientiousness. You can change. The entire field of psychotherapy is based on the idea that you can change. You can change your personality at any age. Now there are certainly a number of cracks in the field, but there are some very good and serious psychotherapists who really do help people. And you can become more conscientious even at the age of 60 or 70. In fact, getting a disease like diabetes often causes people to become more conscientious. They realize they have to or they’ll die.

Brett McKay:

And what about isn’t openness another personality trait?

Daniel Levitin:

Yeah, that’s an important one. And that gets back to what we were just talking about a moment ago. We do become complacent and we tend to close down our social worlds as we age. We don’t want to make new friends. We want to spend time with our old friends. Part of this has to do with something that Laura Carstensen, a great aging psychologist discovered, which is that we tend to allocate our time based on how much of it we think we have left. And 60, 65, 70, 75. These are milestones.

And even if we have a good chance of living to a hundred now, there’s a different sense that your time might be limited than when you’re 20 or 30. And you don’t want to spend it on things that might not pan out. You don’t want to go to spend an evening at a restaurant you might not like, or with a person you might not enjoy, or worse somebody who will make you feel bad about yourself.

But the research says that although that’s a tendency, we have to fight against it, we have to rage against it and try new things. That’s a key to mental health. Being open to new experiences.

Brett McKay:

All right, so that sounds like the takeaway from this, I think, is okay, if you want to have a successful elder, elderly part of your life, if you’re not very conscientious now, and start getting conscientious. So like start saving for retirement and take care of your health now. Exercise, eat right because that’ll benefit you as you get older. Your 80-year-old self will thank your 40-year-old self. And also as you get older, you have to consciously fight that tendency for you to close yourself off to new experiences and just always look for ways to experience new and novel things. So another thing that people associate with old age, is their memory going away or faltering. Do we really become more forgetful as we get older?

Well, certainly some people do suffer memory loss, and it, and it can be debilitating. Of course this is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s. But there is new research that shows this is all been overblown and oversold. That is that, yes memory decline does occur, but it’s not as bad as we make it out to be.

Daniel Levitin:

I’m in a job where I get to deal with 17- and 18- and 19- and 20-year-olds all the time. I’m a college professor. And I can’t tell you the number of times that 20-year-olds, 20 somethings have showed up at the wrong classroom, even, eight weeks into the semester. Or showed up at the wrong time, or forgotten about an exam. Or held up their hand and I called them two seconds later and they forget what they were going to ask.

And 70 year olds have these kinds of memory lapses too. You go to a closet, you don’t remember why you went there. You walk into the kitchen, you knew you had a reason, but you don’t know why you’re there. You retrace your steps, you forget a name, you show up at an appointment at a wrong time. The difference is the narratives. The stories we tell ourselves,.the 20 year old says, “Oh geez, I must drank too much last night.” Or, “Man, I got to get more than five hours of sleep.” Or “I got too many balls in the air.” The 70 year old says, “Oh my God, I’ve got Alzheimer’s. This is the end.” But it’s the same behavior.

Brett McKay:

When you said that, I do that now with just little pains in your body. Like when you’re like 15 or 20, you’re like, “Oh, I might’ve just tweaked it doing whatever.” But now I’m like, “Oh my gosh, this could be cancer. Like, “This is it.” “I’m having a heart attack.”

Daniel Levitin:

Right, Brett, you sound like a catastrophizer.

Brett McKay:

Oh yeah. Well, yeah, I got to work on the neuroticism of my personality.

Daniel Levitin:

Well, and yet a certain amount of neuroticism drives conscientiousness. So if you go to the doctor and they catch that cancer in time, you’ve just won the race. That, that was good. But I guess if you go to the doctor six times a week, that might be on the far side of neuroticism.

Brett McKay:

I don’t do that. I just go to Dr. Google and look things up, which my pediatrician, my doctor probably doesn’t appreciate. So yeah, memory, so it’s not as bad as we think. But what can we do to stem memory loss as we get older? Because it does happen a bit, but not as bad as we think we do. So are there things like proactively we can do to keep our memory sharp as we get older?

Daniel Levitin:

Yeah, I should say that there’s been a lot of talk about brain training games, computer games, doing crossword puzzles, Sudoku. But in fact, there’s virtually no evidence that though those things work. If you do crossword puzzles, you simply get better at doing crossword puzzles. Now there is a small amount of evidence that doing crosswords or other word games help keep your word fluency going. But again, the evidence is thin.

In fact, Lumosity, one of the big purveyors of brain-training games lost a case with the federal trade commission and had to pay a huge fine. So, and there’ve been a lot of lawsuits over false claims here. There’s big money to be made. Everybody wants a quick fix. Buy a $10 app for your phone and improve your memory. Take Ginkgo or ginseng. No, there’s no evidence. Now to be fair, as a scientist, the fact that there is no evidence doesn’t mean they don’t work. It just means we don’t have any evidence they do. And you can decide accordingly for yourself.

But the things that we do have evidence for are, are two things. We’ve sort of brushed up against one of them. One way to keep your memory better is to keep your social circles active, and interact with new people. The reason for that is that interacting with others is about the most complex human activity we can do. It’s more complex than brain surgery, than being a rocket scientist, than solving Sudoku or crossword puzzles. Interacting in a meaningful way with real live people, not necessarily over the phone or Skype, sorry technology, that’s demanding, and that keeps the brain active.

And the second thing that keeps the brain active is his physical movement. Not necessarily exercise, which is the imprisoned corollary of movement, but physical movement, stretching. Resistance training. Walking, especially in nature, in natural landscapes that are perceptually and physically novel and to, to a degree a little bit challenging.

Brett McKay:

So yeah, we can dig deeper into those two things. The benefits of social relationship and exercise. Going back to our common narrative of getting older, we typically think as you get older, you get lonelier because maybe you’ve narrowed down the number of friends you have, or maybe your friends or family members are dying. I remember my grandfather, he lived to be 101. And it was sad. As he got older, I remember he told my mother, he’s like, “All my friends are dead.” And it was really sad. I mean he had family nearby, but it was that, it was really sad for him. So what can older people do to prevent that from happening, where they get to the point where they have no friends.

Daniel Levitin:

Well that is, that is a hazard. I met with George Schultz, the former secretary of state not long ago. He’s 99 now, and he was complaining of the same thing. Most of his friends are dead. Certainly his close friends are dead. I met him about 35 years ago through, I was working for one of his close friends, Edward Edmond Littlefield. And when he Ed and other people who were close to him, it caused a downturn. Fortunately, he maintains an active social life. After his wife died, he happened to marry a younger woman who has a circle of friends who are younger than he. And older women have been known to bury younger men. But it’s not just that. It’s going to church, or to civic groups, or volunteering with the Red Cross or at a hospital or with Headstart. Putting yourself in situations where you are meeting new people.

Brett McKay:

And you highlight, there’s movements within different cities or communities where they’re actually finding ways to get older people to interact with younger people. So there’s instances where there’s like co-living. So you have 20 year olds living with older people in a sort of community. And it helps the old people because they have people to talk to and interact with, and they’re new and young. And the younger people benefit from that because they get to hang out with these old people who have this all this vast experience of life.

Daniel Levitin:

Thank you for reminding me of that. And I love this. So in some cities where there are universities and colleges and this happened out in necessity. Dorm rooms got crowded and the university didn’t have space. So living communities have popped up where college students live with older adults. And everybody loves it.

I think in a number of cases of college students went into it thinking it would be depressing. But they love it. They love the warmth, the love they get from the older people. It helps them to reevaluate what old age means. The older people are having companions who are full of energy and optimism, and are learning new things. So these age mixed living groups are one. Some communities have started intergenerational choirs where young people and oldsters sing together, which is a great bonding activity.

When I was a student, you’re asking me why I wrote the book. I had a number of extraordinary and just plain dumb lucky experiences where my entire life I found myself interacting with people who were in their 80s and 90s. It just happened that way. When I was a kid, I grew up in a small rural Northern California town, unincorporated town, mostly agricultural and ranchers. And we had a post office that was built as part of the pony express. And the US postal service had named an older woman to be the postmaster, which was kind of a highfalutin title because there was really only one employee in this small post office, but every post office has to have a postmaster.

Her name was Eleanor Dickinson, and she was 75 when I was a kid. And when I was eight, she’d have me over her house for cookies and milk, and we chatted and I just loved her stories. And she was a naturalist. She taught me about the bugs and the creatures in her garden. And I had a kind of repeat of this when I was an older student in college. One of my favorite professors was John Robinson Pierce, who was a science fiction writer and a great scientist who had launched the first telecommunication satellite in the early 1960s, Telstar. And when I met him he was 80. He was in his fourth career as a professor at Stanford. And he would have people over to dinner parties of all ages. Students, older colleagues, middle-aged colleagues. And there was no agenda for the dinner parties. Usually it was just to talk and get to know each other. It was a great thing,

Brett McKay:

And this is another, it’s this idea of interacting with new and different people is another reason why older people might want to try to stay on the job as long as they can. Not retire at 60 just because they could.

Daniel Levitin:

That’s absolutely true. I could imagine some people who are in stressful jobs, or jobs they hate, wanting to change jobs and facing ageism, not being able to find a new job. But if you look at work in the broadest possible way, retirement really does signal decline statistically, in an awful lot of people. Your social circles shrink. You’re no longer feeling valued. And so immersing yourself in charitable organizations, political causes, religious organizations, even a book club. Or doing something that keeps you engaged with a meaningful activity to which you can contribute. That’s very, very important. Now it takes all forms. My wife’s grandparents had eight children, and I think 60 grandchildren, and another 35 great-grandchildren. And it was meaningful for them to do family things. Grandma was writing out birthday cards several times a week just to keep up with that. And they were very thoughtful birthday cards. She kept up with what everybody was doing. That was meaningful to her. I don’t presume to tell anybody what’s meaningful to them, but it kept her and grandpa alive well into old age, late 80s.

Brett McKay:

So interacting with your social environment, keeping an active social life can not only just stave off things like loneliness and depression that often happen when you don’t have a social circle, but as you said, it also keeps your mind sharp, improves memories, so do it for those reasons as well.

Then you mentioned another thing that one of the best things we can do to keep our memory sharp and our mind sharp as we get older is exercise, but you said it’s not like getting on the treadmill and walking and while you’re watching Law and Order Special Victims Unit., It’s interacting out in nature. And nature is, again, I think the commonality between nature and social relationships is nature is complex.

Daniel Levitin:

Yeah, and this gets to, this is something that we’ve only recently begun to appreciate in the neuroscience community. My take on this idea is that the body and the brain co-evolved over many millennia, and not just humans but all mammals, and reptiles, and fish. Any mobile creature had to explore its environment in order to find food, find safety, and find a mate. And our brains were basically built for that. And everything got added on in evolutionary fits and starts to support geolocation and geo-navigation. And if we don’t do that, if we stop moving around and exploring the environment, those parts of our brain atrophy quickly. And they support things that are important for other purposes like memory and problem solving. So exercise is good. There’s nothing bad about it. In fact, it can be quite helpful for heart health, and for oxygenating the blood, and hence the brain.

But if you’re focusing mostly on brain health, getting out into the world, into complex natural environments and moving around in them is really important. Especially natural trails where anything could happen, where there are twigs in your way, and roots to trip over and rocks and boulders. Sure, walking around Central Park or Golden Gate Park on a well-paved path is safer, and a good thing. But even better is to get out where a bird or a creature might run across your path and take you by surprise. That’s what’s mentally activating.

Brett McKay:

Sounds like orienteering would be a great hobby to take up.

Daniel Levitin:

Absolutely.

Brett McKay:

This, this idea of movement and navigating being associated with memory. We’ve had a guest on who wrote a book about that topic, about our navigation’s influence on our brain. And one of the sort of interesting research that’s cong out lately is how the reliance on GPS may, it’s not definitive yet, but may have detrimental effects on memory as you get older. Because you rely on the GPS to navigate instead of using your navigational brain, and because your navigational part of your brain is associated with memory, your memory ability sort of atrophies more quickly.

Daniel Levitin:

Yeah, it’s an interesting idea. And you know, science takes a long time, and so we don’t have data yet on this. And of course a lot of things that make intuitive sense didn’t pan out. But from what we know about evolution in the way the brain is structured and wired, GPS enables or provoked to kind of complacency where you don’t have to build a mental map and that can’t be good. Because the hippocampus is the seat of memory. At least it’s where memories are stored and processed and indexed, if not where they actually reside. And we’ve known this for 60 years. And the hippocampus is essential for memory. If it’s damaged, you stop forming new memories. It can become difficult to retrieve old ones. Amnesia typically occurs from some insult to the hippocampus. And the hippocampus evolved for place memory, for navigation. It didn’t evolve necessarily for remembering things like the pledge of allegiance, or Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner, or lyrics to your favorite song.

It evolved to help you navigate and find places and remember where the well and the fruit trees are. And the way it’s built functionally anatomically is that if you’re not navigating or using it for that, the other things can fall by the wayside.

Brett McKay:

So maybe one thing possibly is like use your GPS less. It won’t hurt. But maybe use that less. I do that every now and then, I’ll just like not use my GPS just to get around town for that reason. Plus it’s just more fun to have to figure out how to get somewhere on the fly.

Daniel Levitin:

Well, I think purely from a safety standpoint as somebody who lives in California where earthquakes are a threat, and you know with people who live in Florida and other hurricane places, at some point the GPS system could go down and you may need to leave. That’s happened. In fact, we had a little glitch here in Los Angeles a couple of days ago where the GPS went down for 20 minutes, and I had to get across town.

Now I, like many people, often use it if I’m in a hurry because I want to find the fastest route. It is important to know the general lay of your community. The general routes out and main thoroughfares and some alternate routes in case those thoroughfares are clogged, not just for brain health, although it is good for that, but you know, for the emergency preparedness, if the system goes down and someday it will, you need to be able to navigate.

Brett McKay:

The last thing I’d like to talk about, about our aging brain and how it changes as we get older, is our emotions. And again going to this narrative that we have of what aging looks like. When we think of emotions and older people we think of, they’re the old person with a sour face who’s crotchety and angry and yelling, “Get off my yard.” But your research highlights that actually older people are some of the happiest people out there.

Daniel Levitin:

They are.

Brett McKay:

What’s going on with that?

Daniel Levitin:

And not every older person. There are some crotchety, grouchy, cantankerous old people. But statistically, older adults are happier. In fact, across 60 different countries, 6-0 different countries, the peak age of happiness occurs around 82.

Some of it is that positivity bias. Old people tend to encode. And remember more positive experiences. And some of it is really an appreciation that if you’ve made it to old age, things have worked out for you. Even if you didn’t like yourself when you were younger, or you were self-conscious that other people didn’t like you, for the most part you made it. You’re okay. You know, you might’ve wanted to be a different person, but this person worked out all right.

And whatever accomplishments you’ve had, you can appreciate, most of us. Although gratitude is something we can all work on, and that also helps. But we do have a kind of neural, a neuro-emotional mechanism that kicks in where we appreciate things more. We experience more gratitude. And some of that gets back to gets back to Laura Carstensen is idea that with a limited amount of time you stop and you smell the roses. You, you want to just sit and enjoy what you have and appreciate it. You’re not fighting the treadmill, you’re not constantly trying to climb the ladder. You are allowing yourself to appreciate what you have rather than what you don’t.

Brett McKay:

And what’s interesting about that research about emotions over the life cycle is that it kind of bottoms out at age 50. I guess that’s the point in your life where like you’ve probably reached where you are and you’re going to be in your career likely, and so kind of had that, you’re like, “Okay, this is it.” But then after a while, as you get older, you’re like, “Well, it’s actually pretty good. I’ve done pretty well for myself.”

Well, Daniel, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Daniel Levitin:

Daniellevitin.org. D-A-N-I-E-L L-E-V, like Victor, I-T, like tango, I-N like November, all run together. Daniellevitin.org. And the book should be a available wherever books are sold.

Brett McKay:

Well, Daniel Levitin, thanks so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Daniel Levitin:

Thank you, Brett.

Brett McKay:

My guest was Daniel Levitin. He’s the author of the book, Successful Aging. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about his work and his book at his website, Daniel Levitin.com. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/successful aging. You can find links to resources. Read a little bit deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com. You can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles written over the years about pretty much anything. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so at Stitcher premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com. Sign up, use code Manliness for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher App on Android or iOS and you started joining ad-free episodes, of the AOM podcast.

If you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Stitcher or whatever podcast player you use, and if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you would think would get something out of it. Helps out a lot. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time. This is Brett McKay reminding not only to listen to AOM podcast, put what you’ve heard into action.