Editor’s note: The following chapter on “How Moods Can Help Our Work” was excerpted from The Technique of Building Personal Leadership (1944) by Donald A. Laird.

“Well, that’s that. Now we have hit bottom and there is no way for us to go but up.”

This was the calm comment of a business friend who had just received word that his best customer, for whom he spent more than three million dollars a year, was transferring his business to a competitor.

Only a few weeks earlier I had seen this same man storming and stewing because his firm had lost a customer who spent only twenty thousand a year. Then he was sure that the lost business would ruin him.

Why was he such a poor loser one day, such a good one another, and when he really had bad news? It was because the news of the small loss came on one of his bad days, when he was moody. The serious loss came on one of his good days.

We all have our ups and downs, some of us worse than others. Many persons are handicapped by these, but some have learned how they can actually use these ups and downs to give them greater leadership.

Some persons have dug out their diaries and read back over the entries to see the regular rise and fall of their spirits over a period of years. Some have even made charts from these entries.

One person could not do this because he kept a record only when he was feeling on top of the world. This proved especially useful, however, for he now rereads the entries when he gets in a downcast mood, and the memories thus aroused help make his bad days more bearable.

An unusually successful salesman uses a somewhat similar trick. He has photostatic copies made of his best sales orders and carries these in his wallet. When the blues get him, he looks at these for objective encouragement; they keep his sales up.

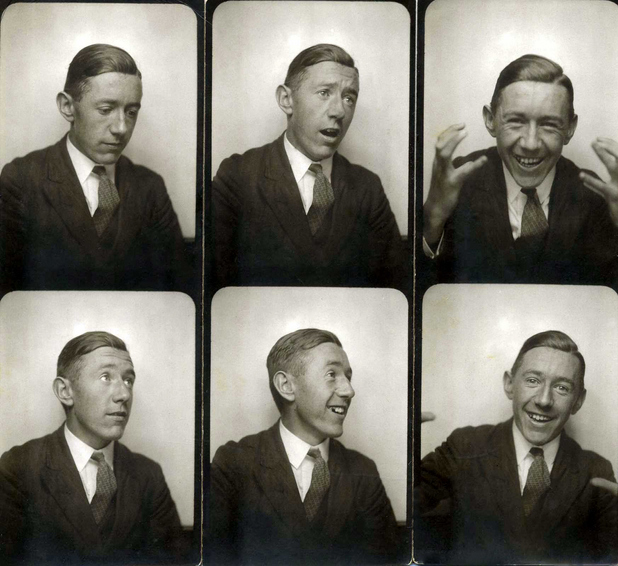

A Philadelphia sales manager had noticed shifts in his moods but had not noted their clocklike regularity. “I have days,” he said, “when my men all seem to deserve a raise. A couple of weeks later, I want to fire the lot of them.”

“When I am up,” he continued, “I think my wife is beautiful, and I’m bursting with pride over my youngsters. I get lots of ideas. I want to be with folks. Then, suddenly, a few days later I’m a changed man. I am down. My wife looks a sight to me, I worry about the kids, I want to be left by myself, and I find fault with everything I have done.”

He might have added that when he is “up” he eats more, walks and talks faster, wakes up early, feels peppy, makes wildcat investments, laughs off criticism and blunders. This is the time to ask him for a raise, a loan, or a new fur coat.

When he is “down” his appetite is poor, he talks and moves slowly, is constipated for a few days, can’t get enough sleep. In this mood, he returns articles he has bought, takes patent medicines, criticizes everything — himself in particular. He loses interest in the opposite sex. This is the time to leave him alone, to praise him and beat it.

Moods like these come and go with almost the regularity of the calendar. The average person takes about four weeks to go from one crest of optimism to the next. He passes through the slough of pessimism about midway between. Some people have shorter cycles, taking only two weeks to go through one, while others have long-drawn-out ones, lasting six months.

Abraham Lincoln had a long cycle, which went to extremes. He was in a down cycle when he left his bride waiting at the altar the first time his wedding date was set. It took him several weeks to get over this bad spell. Lincoln was also in a downswing when he delivered his imperishable Gettysburg Address; that is why he felt it was a complete failure. Such a deep funk possessed him on his inauguration day that detectives were assigned to guard him against possible suicide.

These upswings and downswings of mood are perfectly natural, pestiferous as they may be at times. They do not imply insanity. It is dangerous, however, for us to worry about the moods or not to know how to put them to work.

The shift from optimism to pessimism is usually so gradual that most people do not notice the change. They do not realize the change until they discover themselves in the middle of a dark mood. Then, too, there is a natural inclination to give more attention to the blue days and forget the tiptop ones.

The tiptop days have their drawbacks, especially for executives. It is then that people get into debt, make risky investments, turn out a lot of half-baked ideas, start more things than they can finish.

The bad days have their advantages. They give a contrast that makes the upswing seem more enjoyable, the way olives make other food taste better by contrast. Judgment is more on the conservative and safe side, and people watch their health on bad days.

What causes these changes in mood? They are not related to the moon, menstruation, blood pressure, or any other cycles yet discovered. Maybe the ductless glands have something to do with these moods, but this has not yet been proved.

What makes the downswings worse? Psychoanalysts have found that the depression of the bad days is often due to a person’s feeling of hostility toward others, his bothered conscience, or a feeling that others do not like him.

Our low moods are not caused by bad luck or failures. They seem to start spontaneously. It is not because others criticize us, but because we are, at those times, our own worst critics.

There are some important rules for handling others, or ourselves, during the downswing. We have to humor people then. Criticism only makes them worse; they are already criticizing themselves too much for their own good. It is wise policy to wait until they are out of the low mood before censuring.

People need praise more than anything else, unless perhaps affection, when they are in the downcast mood.

We should avoid important decisions at both extremes of the mood swings. At the one extreme we are too optimistic and at the other too pessimistic to use good judgment.

A widow in Chicago, left with only a large house, had to convert it into a rooming house to make a living. She has been unusually successful by not making important decisions at either extreme of the swing. She first plans remodeling or redecorations, for instance, when she is at the top; she plans as though expense were not a consideration. She is careful not to put her plans into action, however, until she has gone through a downswing, during which the plans are trimmed to fit her budget. The result is the bright decorative plan of an optimistic mood and the low cost of a realistic, pessimistic mood.

A top-notch advertising executive applies the same procedure in his work on a new campaign. After weeks of toying with various possibilities, he waits to start action when he is in the upswing. Then he works with furious speed, yet easily, on the comprehensive plan. This work is laid aside, to be resumed in about ten days, when he is starting into his downswing. He rips the work apart, directing his surging self-criticism against his plan and copy. Only the soundly justified parts remain.

In the “lucid interval,” as he calls it, between the downswing and the crest, he patches together what he tore apart, and, behold! there is a finished advertising campaign that is inspired, yet soundly based. He has made himself and his clients wealthy by thus tempering his brain storms of optimism with the severe criticism of his blue periods. He would be another fellow full of bright ideas that did not work, if he did not temper them by the tearing apart of his downswings.

When a quick decision of importance is necessary, a conference of several executives is wise. Some of them will be in the optimistic phase, some in the pessimistic, and their average decision is likely to be sound. Associates thus are a good balance wheel against blunders due to moods. This is something one-man concerns lack.

Some take to drinking during the downswings. This may give some temporary relief by drugging the blues, but it makes the next spell all the worse from the self-criticism the drinking causes. It pays to ride out the storms of pessimism; alcohol is no ballast for them.

When in the downcast mood we incline to keep to ourselves. But we should force ourselves to be with others. No pampering allowed!

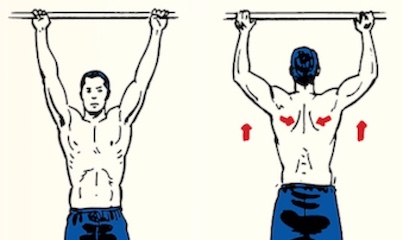

We feel tired, without having worked, when in the downswing. The salesman thinks he should sit in an air-conditioned movie rather than make calls. The executive thinks he needs to relax in his favorite chair at the club. But they need work, not rest. During the downswing, we should work our hardest.