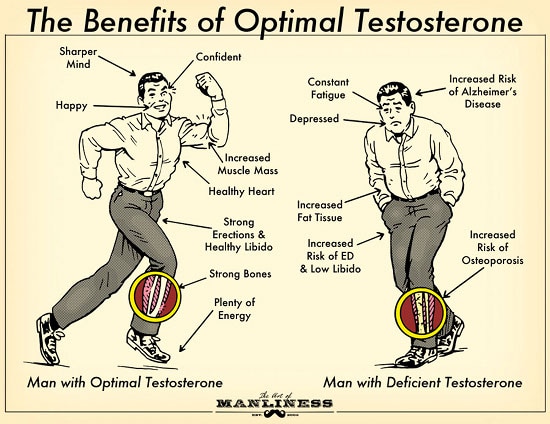

In yesterday’s post we discussed the benefits of maintaining optimal testosterone levels and why you should care about your T. Today we’re going to look into the different kinds of testosterone that exist and how our body produces it. Grasping how testosterone works will help us understand why our own levels may be low and what we can do to boost it in our bodies.

Let’s get started.

The Three Sub-Types of Testosterone

Testosterone is a 19-carbon steroid hormone made from cholesterol that, as we discussed yesterday, provides a whole host of benefits. On average, a man’s body produces about 7 mg of testosterone a day, but not all of that T floating in our bloodstream can be used by our bodies. Our total testosterone can be broken down into the following three sub-types:

1. Free Testosterone. This is testosterone in its purest form. It’s the crack of testosterone, if you will. The reason it’s called “free” is because there aren’t any proteins attached to it. Unbound to other molecules, free T can enter cells and activate receptors in order to work its virile magic on your body and mind. Despite free testosterone’s benefits, it makes up only 2 to 3 percent of our total testosterone levels. To maximize the benefits of T, we want to do what we can to increase the amount of free testosterone in our bloodstream. On Thursday, I’ll share what science suggests we can do to help increase free T.

2. SHBG-bound Testosterone. About 40 to 50 percent of our total testosterone is bound to a protein called sex hormone-binding-globulin (SHBG). SHBG is produced in our livers and plays an important role in regulating the amount of free testosterone in our bodies. The downside to SHBG-bound T is that it’s biologically inactive, meaning our bodies can’t use this type of testosterone to help build muscles or boost our mood. SHBG isn’t bad, but too much of it is. Excess SHBG is why it’s possible to have high total testosterone levels, but still suffer symptoms of testosterone deficiency — the SHBG binds itself to too much testosterone and doesn’t leave enough of the pure stuff. Research suggests that diet and lifestyle changes can help reduce the amount of SHBG in our system, making more free T available.

3. Albumin-bound Testosterone. The rest of our testosterone is bound to a protein called albumin. Albumin is a protein produced in the liver, and its job is to stabilize extra-cellular fluid volumes. Like SHBG-bound testosterone, albumin-bound testosterone is biologically inactive. However, unlike SHBG-bound T, the bind between albumin and testosterone is weak and can be easily broken in order to create free testosterone when needed. Because albumin-bound testosterone is easily converted to free T, some labs lump it together with free testosterone whenever you get tested.

Where & How Testosterone Is Made

A small percentage of testosterone is made in the adrenal glands on top of our kidneys. But the lion’s share — 95% of it — is made in our testicles.

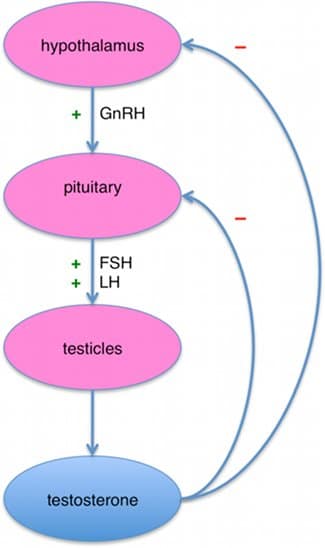

The process by which our testicles produce T resembles a Rube Goldberg contraption, except instead of mice and desk fans moving the process along, our body uses hormones. Below is the Reader’s Digest version of the complex process by which our testicles create testosterone.

1. The whole thing gets kicked off in our brain. When our hypothalamus detects that our body needs more testosterone, it secretes a hormone called gonadotropin-releasing hormone. The gonadotropin-releasing hormone makes its way over to the pituitary gland in the back of our brain.

2. When our pituitary gland detects the gonadotropin-releasing hormone, it starts producing two hormones: 1) follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinzing hormone (LH). The FSH and LH hitch a ride down to our testicles on the freeway that is our bloodstream.

3. When the FSH and LH reach our testicles, they tell them to do two different things. FSH kicks off sperm production, while LH stimulates the Leydig cells in our testicles to create more testosterone.

4. Through a complex process that I’m not even going to attempt to describe, our testicles’ Leydig cells convert cholesterol into testosterone. That’s right, cholesterol is the building block of testosterone. Leydig cells get most of what they need to produce T by simply absorbing the cholesterol floating around in our blood from the bacon and eggs we ate in the morning. If there’s not enough cholesterol in our blood, our testicles can produce a bit of it so that the Leydig cells can convert it to testosterone. But relying too much on cholesterol produced by our nuts (of the non-almond variety) can actually inhibit our Leydig cells from producing T. You gotta eat those eggs!

5. Once T is produced, it’s sent back into our bloodstream. Most of it immediately attaches to SHBG and albumin, becoming biologically inert. The small percentage that remains free and unbound circulates around and starts manning up our minds and bodies. When our hypothalamus detects that we have enough T in our blood, it signals the pituitary gland to quit secreting LH so our testicles ramp down T production.

And that, my friends, is (roughly) how testosterone is made. Here’s a flowchart of the process for you visual learners out there:

Source: Wikipedia

As you can see, the process by which our bodies produce T is complex. This complexity means there are a myriad of ways it can get off kilter and cause our levels to drop. Just from reading about how T is made, you’ve probably thought of some factors on your own that might affect T levels. We’ll delve more into that on Thursday. All in good time.

Tomorrow we’ll take a look at what’s considered a “normal” testosterone level and explore the myriad of ways to get your testosterone tested.

Until next time, stay manly.

Testosterone Week Series:

The Declining Virility of Men and the Importance of T

The Benefits of Optimal Testosterone

A Short Primer on How T is Made

What’s a “Normal” Testosterone Level and How to Measure Your T

How I Doubled My Testosterone Levels Naturally and You Can Too