I’ve seen a statistic thrown around on the internet that 95% of adults over the age of 30 will never sprint again for the rest of their lives.

While these numbers are probably made up, they do capture something that I’ve noticed anecdotally: there aren’t many adults out there sprinting. Heck, if I look at my own life during the past decade, I haven’t done much all-out sprinting myself.

Sure, I’ve done HIIT work on an assault bike, burpees, and bodyweight exercises to get my heart rate up for conditioning, but bouts of running as fast as I can have been few and far between. I’ve sprinted in some ultimate frisbee games or while playing flag football with the boys I coach, but that’s about it.

The last time I did wind sprints as part of a workout was way back in 2016. It had been the first time in years I had run full speed for more than 40 yards. The result? I gave myself terrible tendonitis in my right hamstring that prevented me from squatting and deadlifting for about a month and made sitting down rather uncomfortable. It still bothers me now, seven years later.

After reading that statistic about how few adults sprint after age 30, I felt inspired to figure out a way to take up sprinting again without injuring myself. I want to be an old codger who can still sprint at full speed at age 75 (even if full speed at age 75 will be as fast as my slow jog is now).

Why?

First, I do enjoy playing sports that require sprinting. Ultimate frisbee, flag football, and basketball are some games I play where you sprint. I want to be able to continue to play these games with my kids and even my grandkids.

Second, sprinting is one of those physical skills that could save my life one day. I want to be able to run as fast as possible when my life depends on it without worrying I’ll blow my knees out.

Finally, sprinting is a great workout. You can do it anywhere, and it’s great for anaerobic conditioning. Sprinting can also strengthen lower leg muscles and tendons, enhancing your durability.

To help me get back into sprinting without injuring myself, I talked to Matt Tometz, Assistant Director of Olympic Sports Performance at Northwestern University.

Here’s your guide to sprinting as a grown-up.

Why You Get Injured When You Sprint

If you’ve tried sprinting as an adult after a long hiatus away from it, you may have experienced an injury like I did. While you might think it’s due primarily to age, injuries from sprinting occur frequently, even among elite athletes.

Sprinting is a high-impact, high-strain activity. You’re contracting your leg muscles repeatedly with a lot of force during the sprint. If the muscles and tendons in your legs haven’t been strengthened to handle those forceful, repeated contractions, you’re setting yourself up for a muscle strain or tendon injury.

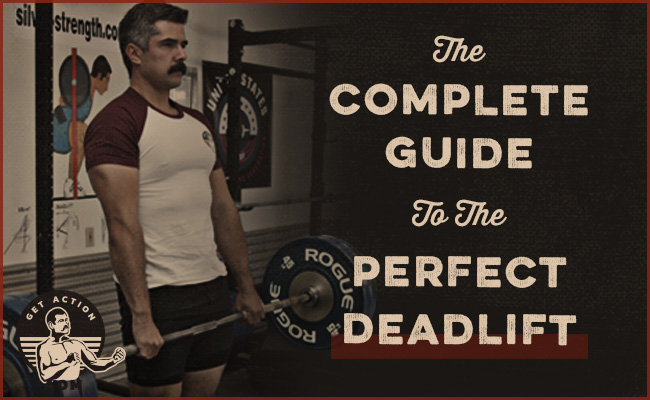

“Think of a sprint as a one-rep max on a deadlift,” Matt told me. “You wouldn’t try deadlifting 405 pounds unless you progressively trained your way to lift that much. You’d just injure yourself if you tried deadlifting 405 pounds without training. The same thing goes with sprinting.”

Preparing Your Body for Sprinting

So, how do we prep our bodies for full-on sprints?

Matt recommends doing a warm-up before your workout that includes both plyometrics and reduced-intensity sprints:

Plyometrics. Matt likes to have his athletes do ankle jumps as part of their warm-up. “Jumping and doing plyos can help strengthen and prepare your hamstring muscles and tendons to deal with the extreme force and tension that’s going to occur when you sprint,” he says.

Matt recommends doing the following plyo exercise: Stand in place with your feet shoulder-width apart. Keeping your knees straight, jump off the ground. As your feet come off the ground, flex your ankles and pull your toes up as high as possible. Extend your ankles shortly before you come back to the floor and push the balls of your feet into the ground explosively. Jump again immediately.

“Do ten reps for a set of two. The goal is to be bouncy and explosive,” Matt said.

Besides ankle jumps, other plyometric exercises you could do to prepare for sprinting include power skipping, alternate leg bounding, and lateral jumps. Do two sets of each exercise. Keep things bouncy.

Reduced-intensity sprints. Before any sprint session, you should not only do plyos but some warm-up sprints as well. The intensity of your warm-up sprints should be around 15% less than the sprints you’ll be doing in your main workout. So if you’ll be doing the sprints in your main workout at 95% intensity, you’ll want to do your warm-up sprints at about 80% intensity.

Do 2-3 warm-up sprints at that 15%-less effort. The goal with warm-up sprints is to practice the movement of sprinting.

Working Your Way Up to an All-Out Sprint Without Injuring Yourself

For individuals who haven’t sprinted in a long time, Matt recommends starting with longer distances but keeping the intensity low. Week by week, you’ll shorten the distance and ramp up the intensity.

For each week’s workout, start with 2-3 lower-intensity warm-up sprints and two 10-rep sets of plyos.

Then perform 3-4 sprints, at the following distances, with 2 minutes of rest between them:

- Week 1: 50-yard sprints at 80% intensity [Matt notes that this “shouldn’t feel like a sprint, but more like a really fast jog . . . . You should feel like you had plenty left in the tank.”]

- Week 2: 40-yard sprints at 85% intensity

- Week 3: 30-yard sprints at 90% intensity

- Week 4: 20-yard sprints at 95% intensity

- Week 5: 10-yard sprints at 100% intensity

Bam. You’ve worked your way up to a full sprint without injuring yourself.

After this on-ramping sequence, Matt recommends slowly adding distance to your sprint workouts while maintaining high intensity.

For each week’s workout, start with 2-3 warm-up sprints at ~80% intensity and two 10-rep sets of plyos.

Then perform 3-4 sprints at 95-97% intensity with 2 minutes of rest between them:

- Week 1: 10-yard sprints

- Week 2: 20-yard sprints

- Week 3: 30-yard sprints

- Week 4: 40-yard sprints

You shouldn’t feel destroyed after every sprint session; you should feel like you’ve left some in the tank when you’re done.

As you can see, this program takes time to add distance. Slow and steady is the key if you want to add sprinting into your workout routine without getting injured.

Keep It Loose

There’s a lot we could get into in terms of proper technique for sprinting, but for the average dude, Matt’s biggest recommendation is to keep things loose and easy when you’re sprinting: “A lot of people think they need to be really tight and have their neck muscles all strained while they’re sprinting. But if you look at elite athletes, they look really relaxed when they’re sprinting. Do the same. Focus on staying relaxed, and it will help keep your form fluid and smooth, which will help with speed and reduce your chances of injuring yourself.”

As a help in staying relaxed, one of the greatest sprinting coaches of all time, Bud Winter, would impress upon his athletes two big cues: “loose jaw — loose hands.” Winter thought that relaxing your hands and jaw (even the lips and tongue) “tends to keep your entire body relaxed.” So try to sprint with what he called the “brook trout look.”

When to Do Your Sprint Workouts

Sprinting can be incorporated into your strength-training workouts.

Matt likes to consolidate stress in his athletes so they have plenty of time to recover. Since sprinting will primarily stress your lower body, you’ll want to do them on the days you do your lower-body strength training to consolidate your lower-body stress in a single workout.

Since Matt’s focus is on helping his athletes get faster, he likes to have them do their sprint work before strength training. “I want my athletes to sprint when they’re feeling the freshest. Also, the sprints can help an athlete feel good and loose before hitting the weights,” he told me.

But as we discussed in our article about whether you should do cardio before weights in a workout or vice versa, doing cardio first does fatigue the muscles, decreasing the amount of contractual force you’ll be able to call upon while lifting. So, if strength training is your primary goal, then consider doing your sprints after your lifting session.

I reckon for most dudes just trying to stay strong and get some sprinting in, it probably doesn’t matter much in the long run whether you sprint or lift first. Do what you prefer.

Experiencing the satisfaction of moving your body as fast as it can truck under its own power isn’t something that should end in your twenties. Keep feeling after your limits and stay in touch with that explosive “Go!” at every age.