Decades ago, society was more bullish on the importance of exercise in weight management. Just go jogging a few times a week, the thinking went, and you’d shed the pounds — never mind that you ended your run by heading to the bagel shop for a big, well-earned, carb-tastic breakfast.

In the last decade, much water has been thrown on the idea of using exercise to manage your weight, and the importance of diet has risen ascendant. Nutritionists and fitness trainers are quick to tell folks that “You can’t outrun your fork!” and “Abs are made in the kitchen!” Which is to say, that when it comes to preventing weight gain, losing the lbs, and keeping lost pounds from coming back, exercising a lot can’t compensate for a poor diet.

Which is perfectly true; diet is the critical factor in weight management. But, as with all cultural trends, once the pendulum on something swings too far in one direction, an overcorrection occurs in which it then swings too far in the other.

What’s gotten lost these days is that exercise is incredibly helpful in achieving and maintaining a healthy weight. While exercise alone (without a modification in diet) is only modestly effective in helping someone lose weight (the more, and more intensely, you exercise, the more effective it becomes), exercise has been shown to be significantly effective in preventing weight gain in the first place, and to be even more important than diet in preventing the regaining of weight after its been lost.

The efficacy of exercise in weight management is due to a number of factors, such as the way it increases lean muscle mass and improves metabolic health. But its most potent factor is one that typically goes unappreciated: the way it regulates appetite.

The Profound Effect of Exercise on Appetite

It’s often assumed that exercise will increase your appetite and make you hungrier. Some people who are trying to lose weight actually avoid it for that very reason.

But as it turns out, active people eat less than inactive people.

In our podcast interview with Dr. Layne Norton, he described a study done “in the 1950s looking at Bengali workers [that] looked at sedentary people, people with a lightly active job, a moderately active job, and a heavy labor job”:

And what they found was from the lightly active to heavily active jobs people pretty much matched their intake without even trying. They just ate more calories and they remained in calorie balance. What they found was the sedentary people actually ate more than every other group except for the heavy labor jobs.

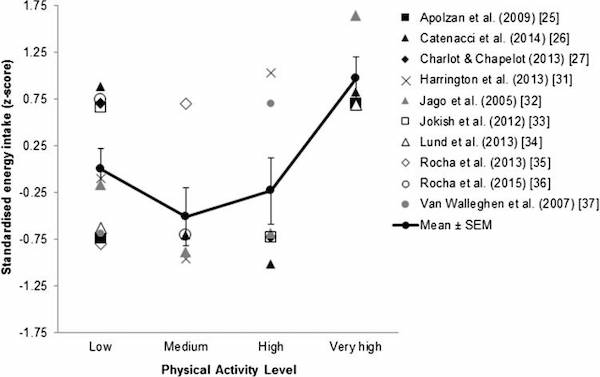

This same result has been born out from more recent studies. As shown in this graph from one, the relationship between physical activity and appetite follows a J-curve:

So to reiterate here: even though they’re inactive, and thus have lower energy intake needs, sedentary folks eat more than even people with high activity levels (the only people they eat less than are those with very high activity levels, who because of the intensity of their activity, obviously have exceptional energy intake requirements). As your level of physical activity increases, so does your ability to match your energy intake with your energy expenditure.

What causes the mismatch between energy expenditure and energy intake for sedentary people, and the healthy coupling between the two for active people?

Well, regular, long-term exercise has been shown to have a kind of paradoxical effect on appetite: it does increase your drive to eat, but, this effect is balanced by an improvement in your appetite sensitivity — your sensitivity to the signals of satiety. So, you may feel a little hungrier overall, but when you sit down to eat, you’re more likely to stop eating when you’re full, and less likely to overeat. As you increase your physical activity, you may eat more, but this increase in caloric intake is matched to your increase in caloric expenditure; you intuitively couple your energy consumption to your energy needs, and stay in a state of caloric balance. This is why exercise is so particularly effective for weight maintenance — keeping off the pounds you’ve already lost. But enhanced appetite control is also helpful in losing weight, as when you’re attuned to your hunger cues and the feeling of satiation, it’s easier to maintain the small caloric deficit that’s necessary to slowly and healthily shed pounds.

Research has not yet been conclusive as to how physical activity regulates appetite. It may have to do with physiological factors, like hormones. For example, those who exercise have lower levels of insulin and greater insulin sensitivity, in part because they tend to have greater muscle mass, and muscles, as Dr. Benjamin Bikman put it in our podcast interview, act like “little mouths that are gonna eat up all that glucose from the blood.” As you lower blood glucose, you lower your craving for food.

But there may be deeper factors at play as well.

One of the prevailing theories as to why we get fat is that our brains are misaligned with our modern environment, in which sugary, fatty, calorically-dense food is available 24/7. According to this theory, since humans evolved in a harsh environment in which we never knew when our next meal was coming, whenever we come across energy-dense food, we’re wired to gorge ourselves on it. That’s why today, we tend to overeat all the delicious food at our disposable. Yet as Mark Schatzker explained on the podcast, the problem with this idea, which he dubs the “hungry ape theory,” is that studies have shown that the human body actually resists gaining weight; instead, it has a generally healthy set point that it wants to stick around. Which makes sense, when you think about it. There may have been an adaptive survival advantage to gorging on calories when you could, but becoming fat, slow, and sick would have become a distinct disadvantage. Becoming obese would have made a primitive human less able to obtain food and more vulnerable to attack. So the human body arguably does not want to gain weight past a certain point, which is why continually eating past your natural satiety signals takes real, uncomfortable effort. At least at first.

It seems, however, and, just to be clear, this is our own theorizing here, that people who become overweight gradually lose touch with these satiety signals for reasons both physiological and psychological. If you rarely move your body, it stands to reason that the connection between it and your mind will weaken. And indeed, those who are overweight often seem disassociated from their physical selves. Exercise, activity, and movement restore the mind/body connection, putting you back in touch with how your body feels, what it “wants.” It seemingly helps restore one’s intuitive instincts. When a human being is living in a natural, “normal” state, that is, getting daily bouts of physical activity, appetite is intuitively regulated, so that caloric intake is naturally matched with caloric expenditure (think again of the Bengali workers).

At the same time, exercise provides a hit of feel-good neurochemicals that people might otherwise turn to food to get. We’ve known for many years now that exercise is just as effective as antidepressants in alleviating depression. Recent research has confirmed that it is highly effective in treating anxiety as well. For folks who use food as a source of comfort and to deal with undesirable feelings, exercise may curb appetite by providing an alternative way to reduce stress and lift mood.

An Argument for Exercise as the Foundation of Weight Management

One of the recent knocks against exercise as an effective tool for weight management is that research has found that when you do a lot of physical activity during a dedicated workout, your body compensates by moving less the rest of the day, so that the workout doesn’t create as great of a caloric deficit as you’d think.

But the real reason exercise is so key to weight management is not its direct effect on the balance between caloric intake and caloric expenditure, but the indirect effect it creates via its impact on appetite.

So while we often trumpet diet as king when it comes to weight management, with exercise seen as the proverbial icing on the healthy lifestyle cake, it’s possible we have the equation backwards. It’s often advised that people start working on their diet first, and then, once they’ve got their eating in order, add in the exercise habit later. But, having the control to stick with a diet may be premised on first building a physical-activity filled lifestyle. Indeed, if folks prioritized getting plenty of exercise, the diet component would almost take care of itself. Almost — we do live in a sort of “toxic” food environment, in which birthday-cake-filled breakrooms, candy-bar-lined checkout lanes, and snack-filled kitchen drawers provide constant invitations to eat, and require even the physically active individual to ask himself, “Am I actually hungry here, or does that just look good?” But in using exercise as the foundation of weight management, the individual will be better able to answer that question accurately, disentangle true hunger cues from boredom or a downcast mood, and move much of the way towards a healthy weight.