Who am I supposed to be?

What am I supposed to do with my life?

These are existential questions that individuals ask themselves throughout their lives. And while they consume a lot of mental bandwidth in your 20s as you take your first steps into adulthood, they still haunt you in your 30s, 40s, 50s, and even 60s, though the tenor of your reflection changes over time. As you get older, you worry less about what you should do with your life, and start worrying more about whether you’ve lived your life right.

There’s a philosopher who spent a lot of time thinking about this existential angst that’s struck many a man as he stands in a grocery store line or lies in bed at night; in fact, he’s the thinker who’s credited with fleshing out the whole idea of existential angst.

I’m talking about none other than Soren Kierkegaard.

Kierkegaard was a philosopher with some truly keen insights into the human condition, particularly regarding what it means to be a “self.” In his book The Sickness Unto Death, Kierkegaard unfolds his idea of what it means to be a self, the emotions and attitudes we can take towards the self, and why we often feel so anxious about what we’re supposed to do with our lives or who we are to become.

Kierkegaard isn’t the most straightforward writer. There are times when I read his stuff, and I want to throw the book across the room because I have no clue what he’s trying to get at. But when you finally realize what he’s saying about the self and our relation to the self, it fundamentally changes the way you think about your own life.

The modern thinker who helped me finally understand and appreciate Kierkegaard’s idea of the self is philosophy professor Gordon Marino. In his book, The Existentialist’s Survival Guide, Marino gives a simplified, accessible explanation of what Kierkegaard was trying to say in The Sickness Unto Death.

Below I share Marino’s outline of Kierkeegaard’s concept of the self. It’s given me a lot to ponder on. Maybe it will do the same for you.

Kierkegaard’s Three Selves

According to Marino, Kierkegaard would say that our identity is made up of three selves: our concrete self, our ideal self, and our true self:

The Concrete Self. The concrete self is who we are now. Maybe, for example, you’re a dude who lives in Ohio, owns a restaurant, has a wife and two kids, likes cycling, and has a generous heart but struggles with anger.

The Ideal Self. The ideal self is the self you want to be. You want to be a millionaire. You want to be 20 pounds lighter. You want to be an Ironman. You want to be calmer. You want to be a man who has it together. These are all versions of your ideal self.

The True Self. The true self is the self God wants you to be, or in Kierkegaard’s words, the true self is the self “rested transparently in God.”

While Kierkegaard’s conception of the true self is strongly influenced by his Christian faith, Marino argues that it can equally apply to non-believers. He says it’s possible to think of your true self as your moral ideal. Or, as Catholic priest Fr. James Martin puts it, your true self is your “best self.”

Your true self transcends the egocentricity of the ideal self. It’s not about what you want; it’s about what the transcendent wants for you and accepting it. It’s moving from asking, “What is the world asking of me?” to asking, “What is my soul asking of me?” Which can be a scary shift. Becoming your true self often requires a leap of faith, which Kierkegaard discusses in detail in his book Fear and Trembling. But that’s a subject for another time.

What Is Despair?

So according to our philosopher friend Soren, our seemingly singular self is really made up of three selves.

He then describes the state of a person who cannot obtain their ideal self or true self.

He calls it despair. And Kierkegaard being Kierkegaard, his concept of despair is nuanced and multifaceted.

We often think of despair as an emotion. Like you’re really sad and just want to lie in your bed with your blinds closed while listening to Snow Patrol. And for Kierkegaard, despair could definitely elicit those emotions.

But according to Marino, it’s better to think of despair as a state of the self. As we’ll see here in a bit, it’s possible to be depressed and in despair or incredibly happy and in despair. The take-home point here is to not equate despair with feelings.

So let’s get into some different types of despair you can be in, according to Kierkegaard. These aren’t all the types of despair, but cover some of the main ones.

The Despair of Not Becoming Your Ideal Self

Let’s start with the despair of not realizing your ideal self. Maybe your ideal self is to become a surgeon. You spend years toiling away to reach this goal, but for some reason your dream is cut short. Maybe you have to drop out of school due to circumstances outside of your control.

Kierkegaard would say the concrete self who wanted to be the ideal self would be in despair. More precisely, the thwarted surgeon would be despairing that he has to be himself without getting to be a surgeon. He doesn’t even want to be the self that isn’t a surgeon, and he hates himself because he’s not a surgeon. He’s in despair.

I know I’ve personally experienced the despair of not being my ideal self. Throughout my adulthood, I’ve made it a goal to be more resilient in the face of setbacks. It’s not that I never bounce back. I do. I just don’t like how long the process often takes, and my initial response to adversity. At first, I catastrophize. I mope. I throw pity parties. Eventually, I get around to responding to the setback in a proactive and effective way, but I could really do without all that initial emotional rigamarole.

So I’ve made goals to stop being like that in the face of setbacks and to act with more resilience. My ideal self is the guy who experiences adversity and just lets it roll off his back immediately.

But I never obtain my ideal self. And then I don’t like myself because I’m not my ideal self. “Why do I have to be this way?” I lament. I’m in despair.

The Despair of Not Knowing Your True Self Exists

Let’s move on to despair related to our true selves. Kierkegaard thinks there are different types of despair you can experience relating to this self. We’ll cover two here.

The first type of despair of the true self is not even knowing your true self exists.

Lots of people are in this kind of despair. They don’t think that there’s something bigger than their personal ambitions in life. It doesn’t occur to them that there’s a self that God or the transcendent would want them to be. They’re not contemplating life’s bigger questions; they’re only focused on the day-to-day.

Kierkegaard thinks people who realize their ideal selves are especially in danger of falling into this kind of despair. Imagine the guy who has a solid life. Good job. Nice family. A modest but beautiful home. He’s got time for hobbies and vacations. Life is good. He’s happy. He’s living the dream.

But it doesn’t even cross his mind that maybe God or the universe or whatever wants him to be something more. Despite being nominally happy, Kierkegaard would still say that this guy is in despair (remember, despair isn’t an emotion; it’s a state), and this kind of despair, the despair of not knowing there’s a true, transcendent self you’re supposed to become, is an even graver kind of despair than the despair of not realizing your ideal self because the moral and existential stakes are much higher. You’re not being the person God wants you to be for Pete’s sake! You’re living below your privileges, potential, and responsibilities.

The Despair of Knowing Your True Self, But Not Doing Anything to Realize It

But let’s say the fellow we described above has a moment of realization that there is more to life than a nice house, a good job, and relaxing vacations. He realizes that there’s a transcendent self that he needs to strive to become. He’s on the cusp of becoming his true self . . . but then he just sits on the idea.

Yeah, he felt the stirring to something higher, but then he went right back to existential sleep. That can happen in a lot of ways. Mostly, we get distracted by worldly concerns. Maybe in the moment of existential ecstasy when our man had his personal epiphany about his true self, he gets a text message from a colleague at work, or the kids are screaming at each other in the other room. Or maybe he feels the itch to scroll through Instagram. The inner voice of the transcendent gets overcome by some family dancing to “Fancy Like” in your social media feed.

Despair.

The other thing that keeps people from realizing their true self is that it can be scary. Becoming your true self often requires sacrificing personal ambitions and desires. Maybe a man feels the call to leave his high-paying corporate job and become a high school teacher. That’s his true self calling. But answering the call will require giving up comfort, money, and status. It’s too much, so he flinches and hangs up on his true self. “Maybe in a few years, true self. When I’m a bit more financially secure, and the kids are out of the house,” he mumbles.

This guy is in despair.

Don’t Kid Yourself: Confusing Your Ideal Self With Your True Self

One thing you got to be careful with in figuring out your true self, is not to confuse your true self with your ideal self.

A lot of pop self-help literature borrows language from existential philosophers like Kierkegaard. So you hear self-help gurus talk about “becoming your true self” and the like. But usually this encouragement to become your true self looks a lot like becoming your ideal self: be a self that’s 20 pounds lighter, a self with a better job, or a self with more money. Those are ideal selves. Ego-driven ambitions. They’re not terrible selves to be, but they’re not Kierkegaardian true and transcendent selves. I’d imagine Kierkegaard would say these gurus selling ideal selves as true selves are in despair and peddling despair.

For more insight into this dynamic, check out our podcast with Mark Edmundson about his book Self and Soul: A Defense of Ideals.

So How Do You Figure Out Your True Self?

So we have a true self we’re supposed to become. How do we know what that self looks like? For Kierkegaard, the Christian, that would mean becoming the self God wants you to become — a child of God, a knight of faith.

How do you figure out the self God wants you to become? Reading scriptures, prayer, reflection. Most importantly (see below), taking action.

What about the non-believer? I’d imagine it’s a similar process. Instead of reading scriptures, you read the very best of human philosophy so you can figure out what a potential moral ideal looks like. You look for examples of individuals who have answered a higher call. You reflect on what your best self would look and act like.

How Do You Become Your True Self?

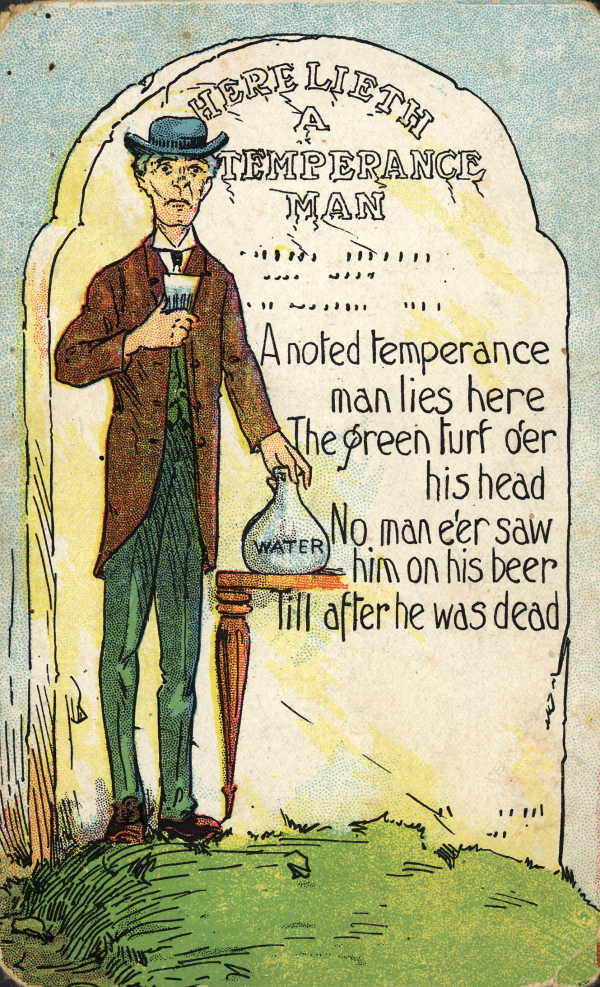

When you feel that stirring to become your true self, take action to realize it! Don’t delay. For Kierkegaard, procrastination was an existential danger. If you don’t immediately answer the call when your true self comes knocking, you’ll have a tendency to get caught up in the distracting day-to-day tasks of your concrete self, and the greater-meaning-submerging ambitions of your ideal self. And pretty soon, your true self just stops calling because it knows you won’t respond. And then you become some Nietzschean Last Man potato head whose only purpose in life is to experience comfort and pleasure. When you die, your tombstone will read, “Here lies a potato head. When the transcendent came knocking, he chose Netflix. At least he was happy. I guess.”

So the next time you feel the impression to do good, to reach higher, do it now, damnit! Lest ye fall into an existential slumber, and deep, deep despair.

For more insights from Kierkegaard and other existential philosophers on living a meaningful life, listen to our podcast with Gordon Marino: