This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction free ebook to read offline at your leisure. Click here to buy.

In this series on the relationship between masculinity and Christianity, we’ve been exploring why it is that women are more likely to be committed to the faith than men.

In our last piece, we discussed how long this gender imbalance has existed and a possible explanation for its cause: that the rise of “bridal mysticism” in the Middle Ages shifted the faith’s ethos in a softer, more relational direction. This in turn led to more women attending church than men, perhaps as far back at the 13th century, and certainly beginning in the 17th.

The imbalance created a compounding cycle of “feminization” that intensified in the 19th century and continues today: ministers cater to their dominant demographic (women), which makes the church more feminine, which keeps men away, which leaves women as the majority of congregants, and so on.

The fact that Christian culture became more feminized in the 19th century isn’t in dispute; the shift has been well-documented by Christian and non-Christian scholars alike. But the rise of bridal mysticism isn’t the only theory as to its cause.

Another, which emerged around the turn of the 20th century, traced Christianity’s “manhood problem” to a different factor: the faith’s disconnect from the physical.

Too much division between body and soul.

The solution to this problem was obvious: reconnect the two. The resulting recoupling project was advanced on a variety of fronts, and became known as “Muscular Christianity.”

In this last installment in the series, we’ll explore this movement and how it influenced, and continues to influence, the Christian religion, as well as Western culture as a whole. This impact was so significant, and the amount of information available about Muscular Christianity both online and in books so relatively sparse, that we’ve decided to give the subject a pretty in-depth treatment.

Not to mention the fact that, as we think you’ll come to agree, Muscular Christianity turns out to be a hugely fascinating subject, especially for anyone interested in the intersection of masculinity, religion, and culture.

Here are just some of the topics this short ebook will cover:

- How Christianity’s reputation for prudery has more to do with Plato than the Bible

- The “crisis of masculinity” that occurred in the late 19th century that’s similar to the one we’re experiencing now

- How Muscular Christianity sought to address that “crisis” and make Christianity more virile

- How Muscular Christians sought to reconcile and find a synergy between their faith and the elements of “primal” masculinity

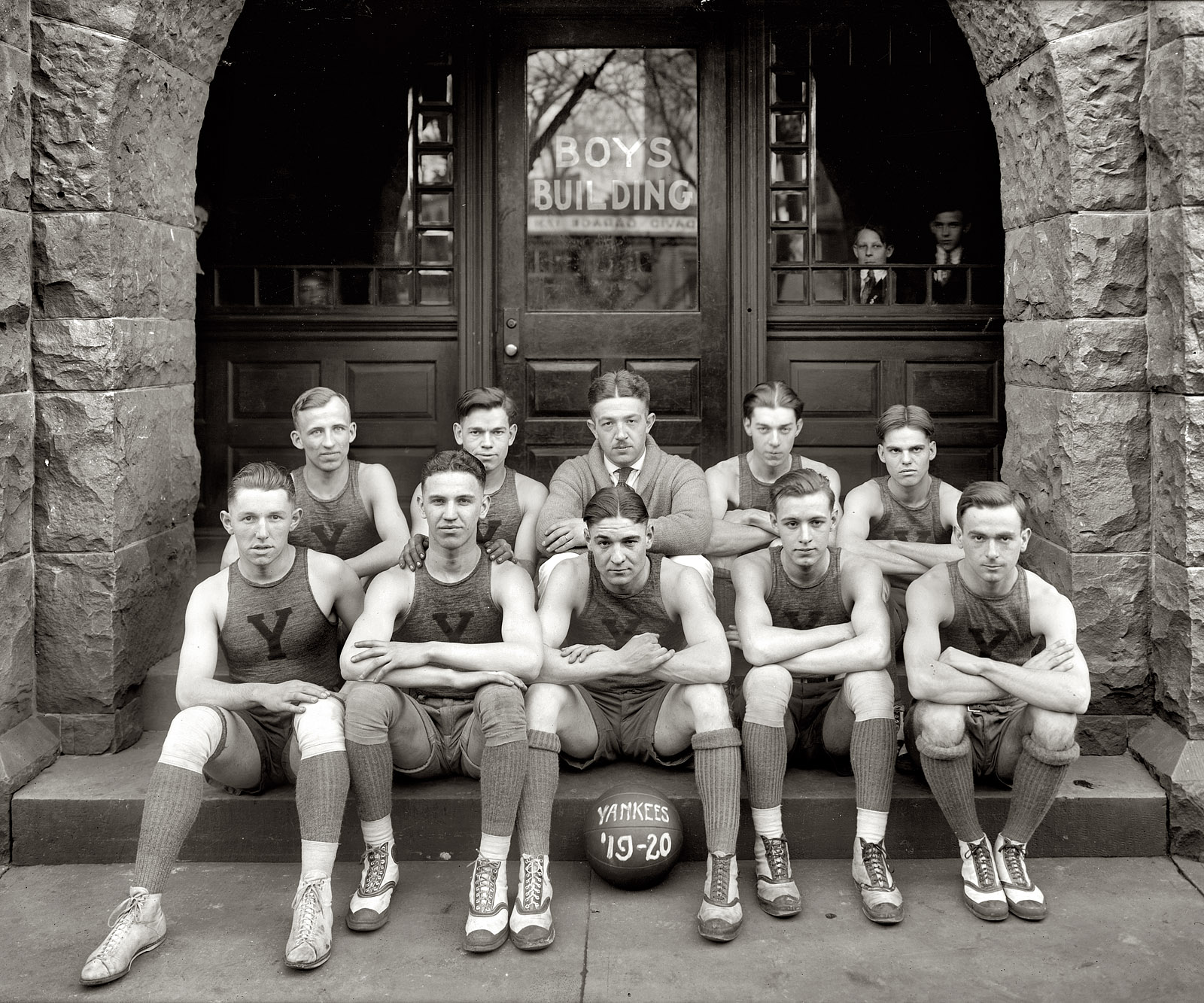

- The religion’s embrace of “gang psychology” and the rise of Christian Brotherhoods

- How Christianity played a major role in advancing the idea that exercise is important and in popularizing sports and gymnasiums

- How Muscular Christianity tried to make church services more virile

- Why Progressivism used to be considered manly

- How Muscular Christianity’s own success helped lead to its demise, and may have even contributed to the rise of secularism

- Whether making Christianity more “muscular” ultimately helped attract more men to the faith

- How Muscular Christianity continues to manifest and impact the religion and the wider culture today

Interest piqued yet? Then let’s jump right in.

[aesop_chapter title=”Part I: Christianity’s Relationship With the Body ” subtitle=”& Its 19th Century Masculinity Crisis ” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/09/box.png” bgcolor=”#888888″]

Christianity’s relationship to the physical body is complex. Just like determining whether the religion is more masculine or feminine in ethos, one can see two different perspectives depending on how one looks at it.

Scripturally, a mind focused on the flesh is said to be in opposition to God. And yet flesh plays a primary role in the act of salvation: the Christian God enters the world incarnate, suffers a physical death, returns with a tangible resurrected body, and promises a similar corporeal resurrection to his disciples.

In the Old Testament, God creates man in his own image, and calls all of his creation good. Yet in the New Testament, Jesus instructs his followers to cut off their hands or pluck out their eyes if they’re sources of temptation.

The apostle Paul uses athletic metaphors in his teachings, encouraging Christians to run the race set before them and press towards the mark. Yet he employs such imagery in regards to spiritual, rather than physical training, and declares that godliness profits a man much more than bodily exercise.

The body is likened to a temple, the very abode of the Holy Spirit. Yet Jesus gives little advice on specific tenets for maintaining that temple, in fact telling his disciples not to worry about what they’re going to eat or drink, and contending that what one puts in their mouth isn’t what makes them clean or unclean.

Given Jesus’ ability to fast for 40 days, and his seeming stamina in walking from town to town and tirelessly ministering to large crowds, the scriptures imply that he had excellent control over his body and was in good physical health. Yet physical health itself doesn’t seem to be a prerequisite for salvation, as many of Christ’s followers included the sick and the lame.

Given this mixed bag of messages, early Christians generally took the tact that the body could be a blessing if properly disciplined, a temptation if not, and that physical health was important, but not as vital as spiritual salvation.

Straddling this line is where Christianity might have remained, had not many early Christian thinkers been influenced by the teachings of that famous ancient Greek philosopher, Plato.

Plato taught that the truest Truth, and realest Reality could not be found on earth or in matter, but up in the heavens, the dwelling place of the “Forms” — the eternal, ethereal essences of all things and ideas. The soul and the body were two distinct things, and the flesh acted as a hindrance to beholding the Forms — keeping one chained inside a cave, gazing at the mere shadows of Truth. The ultimate goal, then, was to transcend the flesh — to escape from the perspective-limiting cave of mortal embodiment and ascend to the heavens.

Platonism influenced many early church fathers, particularly Augustine, who advanced a similar idea of soul/body dualism — that the body and soul are two unified and yet entirely distinct entities that exist in conflict with each other. Of the two warring parties, the soul was the decidedly superior substance.

Platonism in general, and Augustine’s ideas specifically, percolated through Western culture, and as happens over time, got popularly interpreted and overly simplified; people tend to struggle to hold seemingly conflicting ideas in tension, and “the body can be good or bad, depending on how it’s harnessed” became “body bad; spirit good.” The physical came to be associated with that which was base and shameful — an albatross humans had to carry around until their spirit finally got to slip the noose and fly to heaven.

In order to magnify their souls before that day came, early Christian ascetics tried to mortify or ignore the body by starving it, whipping it, or depriving it of sleep. As the 19th century minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson wrote, “The mediaeval type of sanctity was a strong soul in a weak body; and it could be intensified either by strengthening the one or by further debilitating the other. The glory lay in contrast, not in combination.”

Early Christianity and Sports

Unlike the ancient Greeks and Romans, who developed a strong culture of physical training both for war, and for sporting competition, Christianity, with its emphasis on turning the other cheek, and focus on spirit over body, by and large did not create societies with a significant focus on athletics. Nor did they form a philosophy around physical training, as the Greeks did, who regarded a well-developed body as part of the standard of human excellence. Martin Luther didn’t lose sleep over this lack, either, dismissing the Ancient Greek ideal of “mens sana in corpore sano” (a sound mind in a sound body), as a pagan maxim.

This is not to say that all Christians spurned sports. Even the Puritans, who we popularly think put the kibosh on all fun, thought some recreation was beneficial to the spirit, especially that which was productive like hunting and fishing. But they were suspicious of sports involving balls (except bowling) and violent blood sports (like boxing). For the Puritans and other Christians, it wasn’t so much sport itself that was questionable, but the activities that often went along with it, like drinking and gambling, and the fact that games and athletics could become addicting distractions from one’s spiritual focus.

Thus, previous to the 19th century Christendom lacked a vibrant philosophy surrounding the connection between faith and pursing health for its own sake. Exercising the body outside a productive purpose was seen by many Christians as an immoral waste of time, and training to get strong as an end in and of itself was largely a foreign concept.

In On Boxing, Joyce Carol Oates writes that “a man’s masculinity is his use of his body.” Was Christianity’s lack of connection and emphasis on physical culture then the impetus behind why the religion struggled to attract men as the centuries went on, especially more athletic, rugged, virile kinds of men?

Some concerned Christians in the late 19th century certainly thought so. For cultural and economic reasons, the lack of men in the faith’s ranks had seemingly reached a crisis point, and these reformers thought the remedy was plain: to connect (re-connect?) body and theology in order to make Christianity more “muscular.”

The “Crisis of Masculinity” at the Turn of the 20th Century

While it is often thought that a concern over the perceived lack of manliness in society is a recent phenomenon, it has actually emerged periodically for ages, and does so on a cyclical basis.

In times of hardship and war, men’s unique strengths are vitally needed, and in rising to a challenge and sacrificing for a cause, their manhood is confirmed in plain, demonstrable ways. In times of peace and plenty, on the other hand, there aren’t many opportunities for men to exercise the core virtues of masculinity and prove their manhood. A societal debate thus arises as to what the “new role” for men should be, while people wring their hands over whether men are getting too soft — a visceral fear which basically translates into “Things are peaceful now, but what if a crisis came? Could this crop of men protect us?”

We’re in that latter stage now, and such a period was also passed through in the late 19th century. The decades after the Civil War were relatively peaceful on the battlefront, and industrialization was changing the economic landscape. Men were moving from the field to the factory, and also getting jobs in the emerging white collar sector. Earning a living required less sweat of the brow, and more repetitive lever pulling and sedentary mind work. Living in crowded, artificially engineered cities meant men no longer had to pit themselves against nature’s unpredictable elements. The frontier was closing, and so it seemed, was the chapter on American grit.

Just as today, there was much discussion over what being a man should mean in this new cultural landscape. The Victorian honor code emerged to answer that question, redefining manhood as an amalgamation of pious Christian and self-made man. This new standard for male behavior retained the ancient requirement of courage, while emphasizing values needed for economic and social success like pluck, industry, ingenuity, thrift, punctuality, orderliness, cleanliness, politeness, patience, dependability, sensitivity, and refinement.

All good and worthwhile qualities as it went. But as the 20th century approached, there grew concern in certain sectors of society that the softer qualities of manhood had been focused on too much, at the expense of manhood’s sterner stuff. Men, it was feared, had become “overcivilized,” and something distinct and important about masculinity had been lost.

In fact, it’s at this time that the word “masculinity” comes into common usage. Since “manly” and “manliness” had come to be associated with qualities that were fairly gender neutral, writers needed a term that could distinctly connote the more primal, raw, elemental side of maleness.

To some cultural observers in the press, academia, and politics (notably including future president Theodore Roosevelt), masculinity appeared to be in short supply. The emerging crop of Victorian gentlemen had the gentle part of their moniker down, but hadn’t much to speak of as to the man part of the equation. In being excessively high-minded, they had lost touch with the practical realities of life; they could button up their collars but not roll up their sleeves. Looking around at their fellow citizens, these observers saw an enfeebled population that lacked vitality and hearty health, and evinced retiring gentility over forceful action.

The danger of this growing effeminacy, men like TR thought, was that it “let those who stand for evil have all the virile qualities,” while “gentlemen who were very nice, very refined, who shook their heads over political corruption and discussed it in drawing rooms and parlors were wholly unable to grapple with real men in real life.” Who would secure the country’s ideals in an age of “over-softness” and “over-sentimentality,” Roosevelt asked. “Unless we keep the barbarian virtues,” he warned, “gaining the civilized ones will be of little avail.”

While the sources of this cultural feminization were traced to secular institutions like schools (in which female teachers had come to outnumber men), churches came in for a particularly large share of criticism.

As we discussed last time, church memberships in the late 19th century skewed up to ¾ female, and services were described as a “kind of weekly Mother’s Day” — meetings filled with praises to womanhood, sweet sermons, and sentimental music. The ministers and few men who did attend seemed to observers to be even less healthy and more effeminate than the general population.

Christianity was seen as a both a symptom of the overall enervation of the age, and an exacerbator of it. And the religion had seemingly reached a tipping point.

If Christianity had separated men’s souls from their bodies for centuries, the situation had seemingly remained more tolerable in times when those bodies were still actively engaged in strenuous labor; exertion wasn’t directly connected to piety, but men still remained viscerally connected to their physical nature.

But in an age when work became increasingly sedentary and removed from physical realities, men lost interest in attending to yet another abstraction. Rather than participating in one more thing that disconnected them from their bodies, they withdrew from churches, choosing to invest their time in areas that still preserved vestiges of masculinity, like fraternal lodges, saloons, and secular sports.

For men who believed in the compatibility of vigorous manhood and dedicated piety, this situation was intolerable, and it was time to do something about it. So it was that a movement took shape to re-masculinize Christian churches, and the men who attended them.

[aesop_chapter title=”Part II: The Rise of Muscular Christianity” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/09/3_rise-of-copy.jpg” bgcolor=”#888888″]

“Among all the marvelous advances of Christianity either within this organization [the YMCA] or without it, in this land and century or any other lands and ages, the future historian of the church of Christ will place this movement of carrying the gospel to the body as one of the most epoch making.” –G. Stanley Hall, “Christianity and Physical Culture” (1901)

Those who saw Christian churches as epicenters of the Victorian Era’s feminizing culture blamed the faith’s historical emphasis on asceticism and suspicion of the physical body. There was wide agreement in Christian circles, the Rev. Thomas Wentworth Higginson lamented, that “that admiration of physical strength belonged to the barbarous ages of the world” and “that physical vigor and spiritual sanctity were incompatible.” It was commonly thought, he reported, that there was an inverse correlation between a believer’s athletic ability and his piety.

The problem with this prevailing view, another minister posited, is that a religion “which ignores the physical life becomes more or less mystical and effeminate, loses its virility, and has little influence over men or affairs.”

If the feminization of Christianity was rooted in the faith’s lack of physicality, the solution was obvious: to connect the faith to the body. And not just any kind of body — a strong and vigorous one.

An energetic, action-taking ethos championed by Roosevelt as “the strenuous life,” as well as the advent of modern physical culture, were already growing up around 19th century culture generally, and Christians saw an answer in this emerging lifestyle to what ailed their faith specifically. Masculine reformers of Christianity would seek to apply this nascent strenuous spirit and physical focus to their faith in an effort to make it more “muscular.”

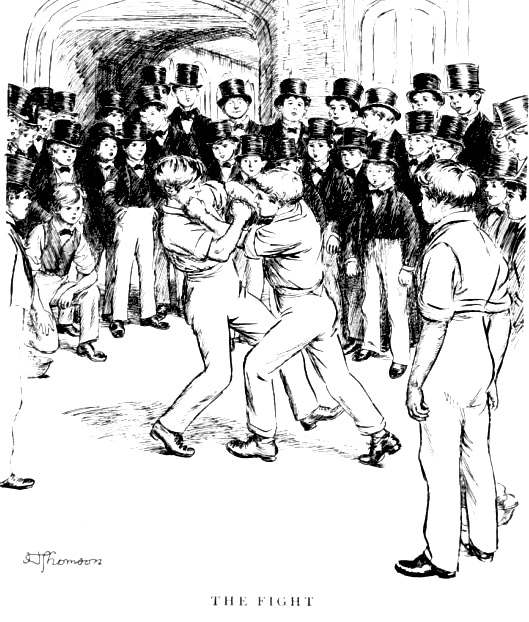

Historian Clifford Putney defines Muscular Christianity “as a Christian commitment to health and manliness,” and as a label and a philosophy, it originated in England in the 1850s, growing out of the novels of Thomas Hughes (Tom Brown’s School Days) and Charles Kingsley (Westward Ho!). Both men believed the Anglican Church was becoming too soft and effeminate, and created protagonists in their books who embodied an ideal counterbalance — young men who managed to combine the virtue and ethics of gentlemanly Christians, with masculine athleticism, camaraderie, and honor.

An illustration from Tom Brown’s School Days, in which the protagonist fights a bully who’s been picking on a frail and sensitive boy. In the book, Hughes expounds on the need to sometimes use violence for the right reasons: “The world might be a better world without fighting, for anything I know, but it wouldn’t be our world; and therefore I am dead against crying peace when there is no peace, and isn’t meant to be. I’m as sorry as any man to see folk fighting the wrong people and the wrong things, but I’d a deal sooner see them doing that, than that they should have no fight in them.”

While Muscular Christianity took off first in England because industrialization and urbanization (and accompanying concerns about a decline in manliness) occurred earlier there than in the States, it eventually migrated to American shores in the 1870s. And here the movement would find an even greater and longer-lasting impact; it remained popular from around 1880 until 1920, and as we’ll see later, continues to influence American culture today.

The Muscular Christianity movement was never officially organized, or headed by a single person, but was instead a cultural trend that manifested itself in different ways and was supported by various figures and churches — predominately those of the liberal, mainline Protestant variety. (Given the gender-neutral, egalitarianism of modern mainline churches, this may come as a surprise, but manliness did not become a hiss and a byword in these denominations until half a century after the movement had died out.)

Adherents of the movement sought to make the Christian faith more muscular both literally and metaphorically — strengthening the physical bodies of the faithful, while pushing the church’s culture and ethos in a more vigorous, practical, challenging, and action-oriented direction.

Let’s start our exploration of Muscular Christianity by looking at the primary plank of its platform: encouraging men to engage in exercise and sports. We’ll then look at ways its proponents tried to make the culture of Christianity more manly.

A Physical Faith

“The least of the muscular Christians has hold of the old chivalrous and Christian belief, that a man’s body is given him to be trained and brought into subjection, and then used for the protection of the weak, the advancement of all righteous causes, and the subduing of the earth which God has given to the children of men.” –Thomas Hughes, Tom Brown at Oxford (1861)

Muscular Christians believed a follower of Jesus could not afford to ignore or mistreat his body, and that physical health could either be a great aid or a significant hindrance to living the gospel.

Because Christendom had not previously had a strong “theology of the body,” muscular Christians had to develop one, creating a philosophy that linked physical health with spiritual health, and offered a rationale as to why striving for strength constituted an obligation of discipleship.

Their argument for a physical faith rested on several premises:

Physical training builds the stamina necessary to perform service for others.

The central tenet of the Muscular Christian philosophy was that the body should be made fit, not simply for health, or for pleasure, but in order to make it a more effective tool for doing good in the world. As Putney writes, the idea was to use “primitive bodies to advance civilized ideals.” Exercise had a higher purpose, which was, as the French physical culturist Georges Hebert put it, to “be strong to be useful.”

Jesus’ endurance in healing endless crowds of people was pointed to as proof of his having this kind of bodily stamina, and his modern followers were encouraged to cultivate similarly unflagging energy in the name of dedicated service. (Muscular Christians also noted that Jesus took time for sleep and solitude, and encouraged rest and recovery for all-around good health.)

How could a man stand on his feet all day working a breadline, or trek to a remote African village to share the good word, if he was weak and in ill health?

As Horace Mann put it:

“All through the life of a pure-minded but feeble-bodied man, his path is lined with memory’s gravestones, which mark the spots where noble enterprises perished, for want of physical vigor to embody them in deeds.”

Physical strength leads to moral strength & good character.

“Perhaps…the system of the New Testament does ‘strike a deadly blow at the development of the body for its own sake,’ but it imperatively demands it for the character’s sake; and boldly teaches that without it, it is not possible to reach the strongest manhood.” –Rev. James Isaac Vance, Royal Manhood (1899)

For Muscular Christians, moral strength and physical strength were not unrelated; disciplining one’s body through athletic training built one’s will, and strength of will was vital to turning down temptation. Teaching the body to obey the mind through exercise, could translate into teaching the body to obey the soul as well; in attuning oneself to natural laws, one could become more attuned to following divine ones. Physical training, after all, is premised on the postponement of present desire in order to fulfill future aims, which is also the basis of Christian discipleship.

Athletics were also seen as healthy diversions from less wholesome forms of recreation and effective conduits for burning off energy that might otherwise seek a less moral outlet. Roosevelt testified to witnessing this effect firsthand:

“When I was Police Commissioner I found (and Jacob Riis will back me up in this) that the establishment of a boxing club in a tough neighborhood always tended to do away with knifing and gun-fighting among the young fellows who would otherwise have been in murderous gangs. Many of these young fellows were not naturally criminals at all, but they had to have some outlet for their activities.”

Athletics were viewed as excellent vehicles for building character as well, as they taught fair play, sportsmanship, delayed gratification, resilience, and so on. Participating in competition has in fact been found to paradoxically be a highly effective means by which to learn cooperation and other moral values.

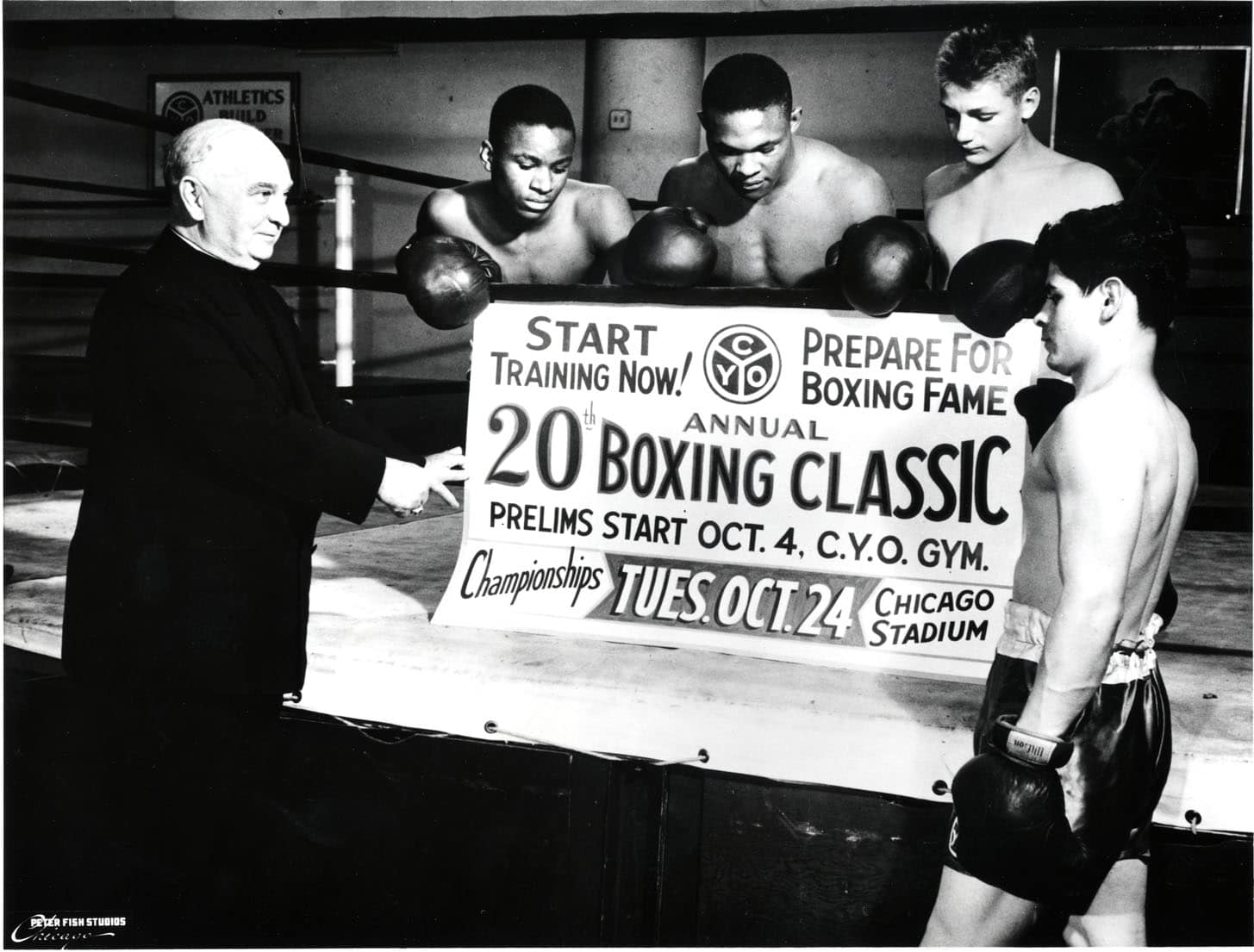

Sports provided a platform to evangelize the “unchurched.”

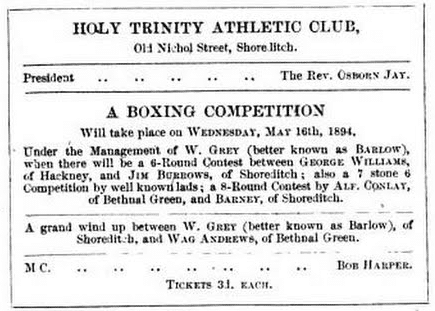

Some 19th century churches saw sports as a way to connect with the kind of highly masculine, rough ‘n’ tumble tough guys they typically had so much trouble attracting. And it worked. An 1894 article about the Rev. A. O. Jay, reports that the High Church clergyman had “discovered that the boxing-gloves are most useful, although considerably neglected weapons in the armory of the church.”

Jay worked in the poorest part of London’s East End, and decided to build an athletics club, which included a boxing ring, right above his church. The club was open every night, and the Father would station himself by the door, taking memberships and shaking the hands of the men who came in. No betting was allowed — just amateur fisticuffs.

Jay worked in the poorest part of London’s East End, and decided to build an athletics club, which included a boxing ring, right above his church. The club was open every night, and the Father would station himself by the door, taking memberships and shaking the hands of the men who came in. No betting was allowed — just amateur fisticuffs.

Not only was the ring consistently filled with competitors, but the brawlers also frequently found their way into the church’s pews, with services regularly attracting as many as 400 men. Jay also reported that participants in the club/church became less prone to ill-intended violence among themselves, as well as towards their families, which was a common problem.

When a Baptist minister criticized Jay’s combination of prayer and pugilism, arguing that “it was utterly against Scripture to get together a lot of hulking prize fighters,” the Father answered that “They may be hulking and they may be prize fighters, but even for them Christ died.”

The minister countered by saying “if boxing-gloves are not carnal, I do not know what is.” To which Jay responded:

“I will venture to inform you there is one thing more carnal than the use of boxing-gloves, and that is to do what you do, neglect the sheep simply, and you call them black because of their utter inability to understand your narrow shibboleths.”

Physical sports and exercise connected boys and men with their masculinity.

Muscular Christians saw athletics as a way for boys and men to re-connect with their masculinity, which they considered a faith-related good, both for the way it would allow men to appreciate and experience their God-created nature, and for the way it would help them fulfill their potential and step into their divinely-appointed roles as protectors of family, faith, and country.

Muscular Christians wanted to see a generation of “Gentleman Barbarians” — men who coupled the traits of essential masculinity with Christian character, so that they possessed both physical power, and the desire and capacity to control and direct that power towards good.

Exercise was seen as an avenue for building masculine traits like strength and confidence, while team sports acquainted men with a sense of honor and camaraderie, rewarded drive and pain tolerance, and developed experience in wielding controlled aggression.

It was hoped by the advocates of Muscular Christianity that sports would prepare virtuous young men to hold their own in the hurly burly of business and politics, for as TR observed, “There is only a very circumscribed sphere of usefulness for the timid good man.”

It was also believed that sports served as preparation for serving in actual war — that what athletes learned on the playing field would translate to the battlefield. Indeed, many looked to sports as what William James called “a moral equivalent of war” — a way to exercise, inculcate, and preserve masculine and martial virtues in times of peace.

For this reason, while muscular Christians supported all kinds of sports, they especially championed more “martial” ones like boxing and wrestling. Roosevelt “always regarded boxing as a first-class sport to encourage in the Young Men’s Christian Association,” as he did “not like to see young Christians with shoulders that slope like a champagne bottle.”

As TR saw it, building up the physical body gave a firmer frame on which to hang the gentler virtues of Christianity. Without such a structure supporting the faith’s softer side, its virtues tended to droop and sag, and come off as mealy rather than noble and respectable. He believed that a man who not only espoused ideals, but could physically stand up and fight for them when justified, would be more respected than he who held high ideals, but let evildoers push him around.

Even in a man who chose to turn the other cheek, a capacity for violence would increase the admiration he was given. He who clearly could fight back, but willfully chose not to, would still be afforded more respect than he whose passivity might as easily be rooted in principle, as forced surrender.

In this way, Jesus might be seen by the faithful as the ultimate “Gentleman Barbarian” — he had the power and capacity to destroy all of his enemies with a wave of the hand, but chose to lay down his life — making the sacrifice not an act of weakness but of perfect and complete will.

What Did Muscular Christians Make of the Weak and Infirm?

In equating physical strength with moral character and dedicated discipleship, Muscular Christianity sometimes approached condemning the weak and infirm as less righteous and generally inferior to their able-bodied brethren (this was the age, after all, when eugenics was becoming a popular idea). Fitness booster Moses Colt Tyler, for example, asserted that:

“since every part of our nature is the sacred gift of God, he who neglects his body, who calumniates his body, who misuses it, who allows it to grow up puny, frail, sickly, misshapen, homely, commits a sin against the Giver of the body. Ordinarily, therefore, disease is a sin. Round shoulders and narrow chests are states of criminality. The dyspepsia is heresy. The headache is infidelity. It is as truly a man’s moral duty to have a good digestion, and sweet breath, and strong arms, and stalwart legs, and an erect bearing, as it is to read his Bible, or say his prayers, or love his neighbor as himself.”

Tyler does, however, ends his exhortation with something of a caveat, laying down the following as the creed of Muscular Christianity [emphasis mine]:

All Attainable Health Is A Duty. All Avoidable Sickness Is A Sin.

If some Muscular Christians did have little tolerance for those who fell victim to preventable disease, and came close to calling the sick, sinful, most saw little scriptural support, and plenty of contradiction, for casting out the infirm. Rather, they preached that a healthy body was the ideal that all who were able should strive towards, while also acknowledging that good health was not always within an individual’s control, nor constituted a prerequisite to salvation.

Physical strength and vigor did not win God’s special favor in and of itself, but simply made the body better prepared to perform his service. The sick, after all, would need the well to help them; if everyone was down in a ditch, there would be no one able to pull the others out.

Christianity as the Sponsor of Sports, Exercise, and Physical Health

For all the reasons mentioned above, proponents of Muscular Christianity sought to get churches to promote and support physical exercise and athletics. Prior to the 1880s, most Christian churches were quite resistant to the idea, seeing sports as sacrilegious, frivolous distractions from a focus on faith, and/or attractors of vice.

But most mainline denominations ultimately changed their minds and got on board, not only because they came to believe in sports as a way to build Christian character, but also out of self-interest; athletics were growing in popularity in the secular culture, especially among young men, and churches felt that getting involved with sports would help them stay relevant, attract new members, and hold on to the rising generation. Churches also figured that if sports were going to go on with or without them, they might as well get involved, and steer athletics in a righteous direction — offering moral leadership and oversight to minimize the chance or immoral pitfalls, maximizing the potential of games for good, and pointing athletics towards “the glory of Christ.”

To this end, churches took both a direct and indirect role in the Muscular Christian movement. In some churches, ministers simply encouraged their members to get more exercise. Others formed their own sports leagues and built athletic facilities — swimming pools, gymnasiums, basketball courts, bowling alleys — inside or adjacent to the worship building. Moses Colt Tyler approved of this trend, arguing that “Every village that has two churches now should just put both congregations together, to worship in one building and to practice gymnastics in the other.” Such reorganization of facility use, he mused, would produce “more godliness in this land, and more manliness, too.”

The different athletic clubs individual congregations formed sometimes joined together in city-wide leagues for intermural competition. One such league in New York City ecumenically embraced the clubs of 15 different Catholic and Protestant churches, and boasted 3,000 members. According to a report written in 1907, in its five years of existence, the “Church Athletics League” had “been an unqualified success” on a variety of fronts:

“From a general standpoint its influence has been most beneficial in stimulating interest in the various parish organizations maintained to develop the social side of church life. It has proved attractive in drawing into these social clubs young men who might otherwise find them uninteresting. The influences surrounding them there have been helpful, no matter in what surroundings their home lives may have been cast. The testimony of all the leading church authorities has been highly commendatory of the general benefits of the league‘s work, both physiologically, mentally, and morally, and they have been most anxious to foster and encourage the extension of the league’s activities.”

The largest faith-based backer of athletics wasn’t any church, however, but the Young Men’s Christian Association. Started in 1844 in London to be a kind of wholesome home away from home for young people who had recently moved to the cities, the YMCA initially offered these transplants reading rooms, Bible studies, libraries, and comfortable chairs in which to study.

Then in 1869 the New York City YMCA started the first Y-sponsored gymnasium, and it proved so effective in furthering their Christian outreach, that other Y’s across the world soon followed suit. “By 1880 fifty-one associations maintained gyms and by 1900 four hundred fifty-five did so,” Putney reports. “Those that did not, noted Association secretary Sherwood Eddy, gradually ‘disappeared.’”

In addition to gyms, Y’s built swimming pools as well as basketball and volleyball courts (both sports were invented at YMCAs), and sponsored hiking, biking, baseball, and rowing clubs. People flocked to these recreational hubs; by the early 1900s, 1 out of every 181 Americans, and 1/3 of college students were either active or associate members of the Y.

By offering physical recreation along with worship services, Bible studies, libraries, and lectures, the YMCA found a winning strategy for attracting and maintaining faithful members. The inverted red triangle, which was adopted as the Y’s symbol in 1891, is meant to represent the ideal of harmonizing and balancing body, mind, and soul, and also represents well the aims of the Muscular Christianity movement as a whole.

[aesop_chapter title=”Part III: Metaphorical Muscularity” subtitle=”Efforts to Reinvigorate the Christian Ethos” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/09/4_metaphorical2-copy.jpg” bgcolor=”#888888″]

“Jesus warrants no sensuous rhapsodies about what is called downy couches, spread by angel hands, but rather a spirited muscular piety, a splendid kind of stand-on-your-feet trust.” –Jenkin L. Jones, “The Manliness of Christ” (1903)

Muscular Christianity had two aims: to increase men’s commitment to their health, and to increase men’s commitment to their faith.

The introduction of athletics went towards the first goal, helping “overcivilized” men of the 19th century rediscover their masculinity and build bodies that would aid them in their Christian discipleship.

But how to help men become dedicated disciples in the first place? How could Muscular Christians entice men into the pews at church, and inspire them to increase their participation in the faith?

The answer they proposed was to create a muscular ethos within Christian spirituality which would match the muscular physique of men’s bodies. This effort to introduce more virility into church services, as well as the religion’s culture as a whole, was advanced on several different fronts.

Masculinizing Church Services

As previously discussed, from the pulpit to the sermon to the hymnal, churches during the 19th century had a distinctly delicate and feminine sensibility, which many would-be male congregants found off-putting. The result was a membership sex ratio that severely skewed towards women, on the order of 4:1.

As previously discussed, from the pulpit to the sermon to the hymnal, churches during the 19th century had a distinctly delicate and feminine sensibility, which many would-be male congregants found off-putting. The result was a membership sex ratio that severely skewed towards women, on the order of 4:1.

Muscular Christians thus tried to interject a more masculine vibe into turn-of-the-century church services, reinvigorating everything from the sermons to the songs, in an attempt to get men back to church.

Manlier Ministers

“Men are liable to lose respect for your traditional position when they lose respect for your muscles. Lose the sickly white color of the speculative realm of study, and take on the more attractive brown of the actual life of men.” –Advice of “Pitching Parson” Allen Stockdale, a former college baseball player, to his fellow ministers (1914)

The effort began with encouraging more virile men to become ministers. Pastors of the period had a reputation for being effete mollycoddle types who spent their days sipping tea with old ladies and pleasing women, rather than playing sports and holding their own with men. Muscular Christians felt that this image of the man behind the pulpit needed to change — that if average congregants were spending more time becoming strong and strenuous, they’d expect the same from their pastors.

Ministers who evinced greater virility, it was thought, would attract the respect and notice of masculine men. Faithful church attender John D. Rockefeller posited that “the more of virility and of rugged manhood there is in the pulpit, the more will the vigorous men of the city be influenced by its message.” An administer for the YMCA echoed a similar message, offering the opinion that while “it is not requisite for a minister to have a handsome face, for that is something that he cannot entirely control…I do say that a finely proportioned body, well developed chest, broad shoulders, and standing square on the feet, gives any man a decided advantage in any calling in life and especially in the ministry.”

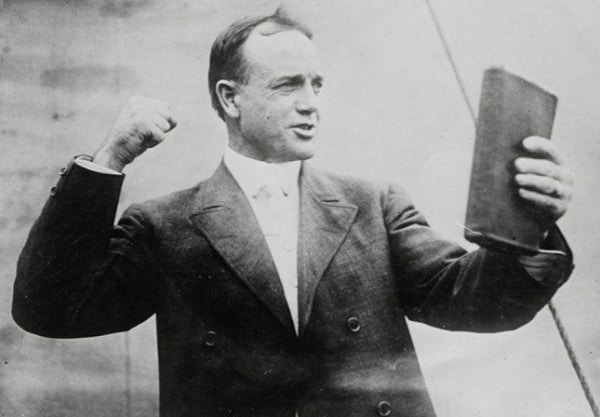

Preachers who were once respected athletes obviously were ideal types to muscular Christians, as they embodied the synthesis of faith and fitness. The most famous of these sporting sermonizers was Billy Sunday. After converting to Christianity, Sunday left a career as a popular professional baseball player to become first a YMCA secretary, and then a traveling evangelist.

Sunday would stage baseball games between teams made up of local businessmen, playing on both sides, in order to drum up publicity for his revivals. In his sermons he preached old fashioned hell and damnation, but tried to be down to earth — talking colloquially, employing sports metaphors, telling stories, using slang, and speaking frankly about sin, including sex. His preaching style was wildly kinetic; he would stand on top of the pulpit, sprint and slide across the stage (as if he were sliding into home), and even smash chairs to emphasize his points. Some were scandalized by these antics, but many, especially men, loved it. Huge crowds flocked to Sunday’s meetings, and over the course of his career, it’s thought he preached to 100 million people, and made over a million converts.

Punchier Sermons

Muscular Christians not only called for manlier ministers, but more men-friendly sermons as well. These messages didn’t necessarily need to involve chair smashing, but according to one survey conducted by a data-seeking clergyman, men desired “shorter,” “pithier” sermons, that were less otherworldly and more relevant to their lives and careers. “This is a practical age,” explained a Methodist pastor in 1911, “and needs wholesome truth set before it in vigorous and practical forms.”

Hymns

The music of church services was another area muscular Christians thought could be improved, and they were in fact successful in introducing more “masculine” songs into hymn books. In 1915, hymn composer Charles Richards reflected on how tastes in church music had changed over the years; rather than engaging in the “too frequent use of plaintive and melancholy songs, which imply that the harps are still to be hung upon the willows in a strange land,” congregants of the early 20th century wanted:

“songs of courage, of cheer, and of triumphant faith. They are not singing as much about heaven as they used to. They are singing more about the Kingdom here below which is to transform the earth into a heaven when the victories of Christ are complete. They are not singing songs of vague and dreamy sentimentality as of old. They are singing songs of character, of service, of brotherhood, of Christian patriotism, of aggressive missionary spirit, of the practical Christian life.”

In 1910, a hymnal especially “adapted to the needs of male singers” was introduced. Manly Songs for Christian Men featured hymns with titles such as “Comrades of the Cross,” “Strong Brave and True,” “The Call for Men,” and “Can the Captain Count on You?” which included lyrics like:

On the great world battlefield

There is need for manhood’s might,

And a faith that will not yield

In the thickest of the fight;

Men with hearts as true as steel

In the cause of human weal,

Men to God and manhood true,

Can the captain count on you?

Iconography Depicting a More Masculine Jesus

The final area in which muscular Christians sought to incorporate a greater portion of virility was in the artwork which adorned the walls and stained glass windows of churches. They felt that Jesus was unfairly, and too narrowly depicted in most Christian art as weak and effeminate, a portrayal that didn’t do justice to the rugged, forceful figure they saw depicted in the scriptures.

To spur the creation of art showing Jesus in a more masculine light, in 1906 a group of Cleveland businessmen commissioned 10 new portraits of Christ, and then toured the exhibition around the country.

Putney notes that manlier depictions of Jesus and his holiest followers also made their way onto stained glass; “Images of Christ looking strong and purposive were common in Progressive Era church windows, as were saints garbed as knights and carrying swords.”

Emphasis on the Social Gospel

“If we read the Bible aright, we read a book which teaches us to go forth and do the work of the Lord; to do the work of the Lord in the world as we find it; to try to make things better in this world, even if only a little better, because we have lived in it. That kind of work can be done only by the man who is neither a weakling nor a coward; by the man who in the fullest sense of the word is a true Christian…We plead for a closer and wider and deeper study of the Bible, so that our people may be in fact as well as in theory ‘doers of the word and not hearers only.’” –Theodore Roosevelt

While Muscular Christianity did push for changes to worship services, one of the philosophy’s main tenets had nothing to do with what was inside church walls, but rather involved looking outside of them at what could be done to serve the community at large.

Muscular Christians were frequently big proponents of embracing what was known as the “Social Gospel.” This movement, which emerged at the turn of the 20th century, charged Christians with applying the obligations and ethics found in the gospels to issues related to health, corruption, economic disparities, and social justice, including but not limited to, poverty, alcoholism, crime, unemployment, child labor, unsafe foods/water, and inadequate schools. The Social Gospel movement was considered to be the religious wing of the Progressive movement, which aimed to marshal the tools of science, technology, and economics to alleviate suffering and improve the human condition.

It may seem strange to the modern reader that a manly, muscular movement was associated with “social justice” and “progressivism,” in the same way it may have been surprising to learn that its biggest supporters were “liberal,” mainline churches, since in modern times, these labels are often popularly associated with views that are antithetical to the upholding of traditional masculinity. (This is not a partisan dig; women are significantly more likely to attend mainline churches and belong to the Democratic party — the political torch bearer of progressivism).

But in the early 1900s, these associations had not yet emerged, or at least hardened. There was no unification or agreement on specific issues among adherents of the Social Gospel, so that some were socially conservative, but politically liberal, or vice versa. And though some progressives did advocate for very liberal causes like Socialism, this kind of stance, even if vehemently opposed on its merits by more conservative citizens, wasn’t necessarily considered “unmanly,” since political radicalism was then associated more with bomb throwing than latte sipping.

For muscular Christians, the Social Gospel, whether directed towards political, economic, or societal ends, was definitely manly for several reasons:

“An individual gospel without a social gospel is a soul without a body, and a social gospel without an individual gospel is a body without a soul. One is a ghost and the other a corpse.” –E. Stanley Jones

The Social Gospel put the impetus of discipleship on grappling with the physical realities of the here and now.

Rather than dwelling on otherworldly concerns, and waiting for things to be made right on Judgment Day, Social Gospellers sought to operationalize the Lord’s Prayer: “Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” Rather than withdrawing from conflict, and passively, timidly sitting on their hands, waiting to trade in their mortal home for a cloud and a harp, Social Gospellers waded into “the arena” and confronted evil, pain, and sickness straight on.

Social Gospel projects often required physical strength and stamina.

Christian adherents of the Social Gospel built shelters, ran summer camps, tended to victims of emergencies and disasters, and taught night classes after their day jobs were through. Embracing an active, practical faith helped make clear the connection between the gospel and their bodies, and motivated disciples to stay in tip-top shape.

Social Gospel projects intersected with the public sphere.

In a way that internal roles at church rarely did, Social Gospel projects called upon men to engage with politics and business — which were then considered distinctly masculine domains — and to solve problems using the skills and leadership abilities they had developed in their professional careers.

The Social Gospel offered the kind of hard, “heroic” challenges men are drawn to.

“There is not enough of effort, of struggle, in the typical church life of today to win young men to the church. A flowery bed of ease does not appeal to a fellow who has any manhood in him. The prevailing religion is too comfortable to attract young men who love the heroic.” –Josiah Strong, The Times and Young Men (1901)

The Social Gospel evoked the code of manhood’s ancient chivalric charge to protect the weak and vulnerable. In publicly taking stands on sometimes unpopular issues like temperance or gambling or political corruption, men had to put their skin the game, and incurred the risk of ridicule or blowback for their views.

In short, the Social Gospel offered opportunities to do good in ways that effectively scratched the masculine itch for action. Muscular Christians had found that the more internally-focused a church was, the more feminized its culture became, while the more outward-looking a church was, the more masculine its membership.

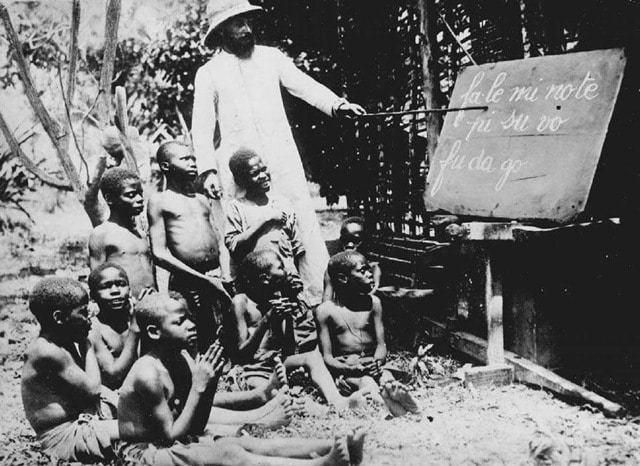

International Evangelism

While international evangelism is not ordinarily grouped in with the causes of the Progressive Era, the impulse which created a surge of interest in the former during the same period, is actually not unrelated to that which animated the latter, and muscular Christians supported missionary work for the very same reasons they did the Social Gospel.

Imperialism is now a dirty word is most modern circles, but during the 19th century, many found the idea of carrying, and sometimes imposing, Western culture, religion, government, and technology abroad to be inspiring and actually altruistic. And this imperialistic drive is part of what animated the Muscular Christianity movement.

Muscular Christians encouraged American men to stay brave and fit, in order to serve in the military should a foreign power draw the country into war or invade its borders. But some (like TR) also felt there could be circumstances in which it was justified to do the invading ourselves.

Others did not support the idea of entering other nations with bayonets fixed, but did champion the idea of traveling abroad with Bibles outstretched. For Christian missionaries, sharing the gospel was an obligation of the faith, an act of service to the recipient, who was in vital need of its saving message. They sincerely believed they were improving the condition of the lives of foreign peoples, in the same way progressives believed they were improving communities domestically.

Proponents of Muscular Christianity supported these evangelistic efforts for all the reasons they supported the Social Gospel — it offered the chance to exercise one’s faith in a practical, risky, physically challenging way. Given the zeitgeist of the age, and the increasing accessibility of travel, the popularity of international missionary work took off, especially amongst young people, without much needed boosting from muscular Christians; for example, the Student Volunteer Movement, founded in 1886, recruited over 6,000 college-age volunteers willing to commit to “The evangelization of the world in this generation.”

The focus of muscular Christians on international evangelism, then, was not to increase the number of missionaries per se, but to bring parity to the increasing gender gap in their ranks. In 1830, 51% of American missionaries had been men, but by 1893, that number had fallen to 40%. Why? As the American economy became more and more competitive, men found it increasingly impractical to drop out of the marketplace to spend years at a time living on little to no money, building the kingdom of God in some far-flung locale. Women, on the other hand, welcomed the chance to escape the confines and social strictures of bourgeoisie society.

To entice more men into the field, muscular Christians emphasized a mission’s heroic, adventuresome, quest-like nature, as well as the fact that evangelization was beginning to be run more “scientifically” — more like a business enterprise, with a greater use of data. Far from being effeminate, muscular Christians argued, it was an endeavor that came with numerous intangible benefits to the development of one’s manhood, which Roosevelt enumerated to the son of a friend who had decided to answer the call:

“It takes mighty good stuff to be a missionary of the right type, the best stuff there is in the world. It takes a deal of courage to break the shell and go twelve thousand miles away to risk an unfriendly climate, to master a foreign language, perhaps the most difficult one on earth to learn; to adopt strange customs, to turn aside from earthly fame and emolument, and most of all, to say goodbye to home and the faces of the loved ones.”

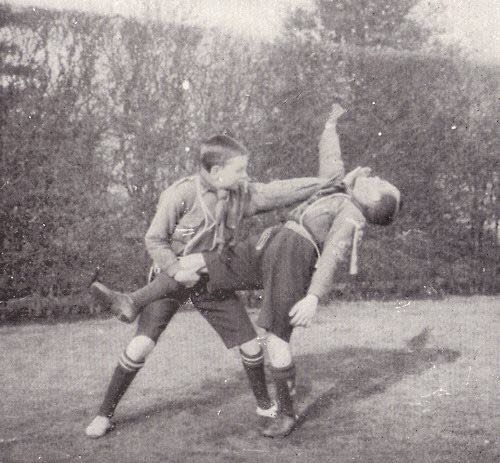

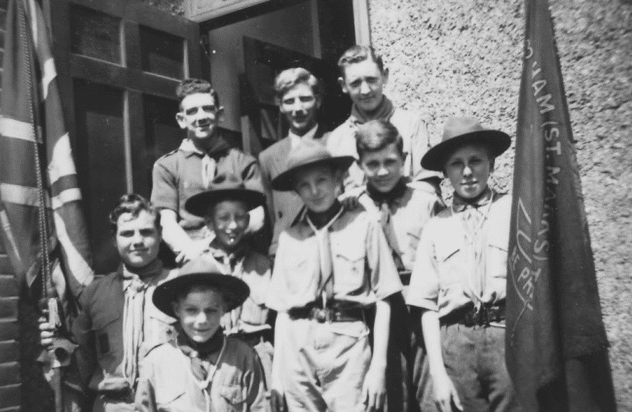

Scouting for Boys

If muscular Christians were concerned about the virility-sapping effects of urbanization and industrialization on grown men, they were even more concerned about the fate of boys growing up in such an enervating age. What would become of boys who never had the chance to grow up learning outdoor survival skills, becoming acquainted with the exertions of farm labor, and finding constellations in the night sky? Would they become “overcivilized” and lose the values that had made the county great — self-sufficiency, courage, the spark of wild masculinity?

These abstract questions brought forth some very specific actions.

In both England and the U.S., several scouting programs — including the Boys’ Brigade (founded in 1883), the Woodcraft Indians (1901), the Sons of Daniel Boone (1905), and most famously, the Boy Scouts (1908 in England; 1910 in America) — emerged with the aim of ensuring that boys continued to learn and pass down the kind of rugged, “pioneer” skills their forebearers had known. Often organized with a paramilitary ethos, including uniforms, salutes, and badges, these organizations also aimed at instilling the principles of discipline and good citizenship in their charges.

One of the earliest Boy Scout badges was the Master-at-Arms badge, which required Scouts to master 3 of the following combat skills: single stick, boxing, ju-jitsu, wrestling, quarterstaff, and fencing.

From the start, of course, the programs emphasized faith in God as well, with the requirements as to the specificity of that faith differing between organizations. For example, the Boys’ Brigade began and remains an exclusively Christian organization. Robert Baden-Powell, on the other hand, required his Scouts to believe in God, without specifying their adherence to a particular religion; while he originally felt the context of the requirement implicitly pertained to Christianity, he later decided it could be left open to interpretation.

Nonetheless, early Scouting was intimately connected to Christian, most often mainline Protestant, churches; not only were 80% of troops sponsored by churches in 1915, almost a third of scoutmasters were ministers. Consequently, boys came to associate their faith with the active and practical, perhaps solidifying their commitment to it; while the average rate for boys dropping out of Sunday School was 60-80%, among those who belonged to church-sponsored Boy Scout troops, it was only 10%.

Muscular Christians not only celebrated Scouting for the way it enhanced and refined a boy’s skills-set, character, and faith, but also for how it put him in touch with his primal side — both socially and environmentally.

Researchers in the early 1900s had begun to study the nature of what they realized was boys’ primary social unit — the gang — leading them to conclude that experiencing its ethos of camaraderie, loyalty, and honor played an important role in male development. The famous psychologist G. Stanley Hall declared that:

“The gang spirit is the basis of the social life of the boy. It is the spontaneous expression of the boy’s real interests. A boy must have not only companions but a group of companions in which to realize himself.”

Psychologists also felt that the gang’s dynamics could be actively directed towards positive ends. J. Adams Puffer, who had studied boys’ gangs, concluded that Scouting was singularly successful in doing this, positing that of “Of all present-day organizations for the improvement and the happiness of normal boyhood, the institution of the Boy Scout is built at once on the soundest psychology and the shrewdest insight into boy nature”:

“The Scout Patrol is simply a boys’ gang, systematized, overseen, affiliated with other like bodies, made efficient and interesting, as boys alone could never make it, and yet everywhere, from top to bottom, essentially a gang. Other organizations have adopted gang features. Others have built themselves around various gang elements. The Boy Scout Patrol alone is the gang.”

Scouts were able to reconnect with elemental masculinity not only in their gangs, but on camping trips in the woods.

Muscular Christians encouraged men of every age to spend time in the outdoors, but thought these excursions were especially important for impressionable, still-developing young men. It was out in fresh air and under open skies that one could strip off the patina of civilization and leave behind the “moral degradation” of the cities in order to re-connect with God, and find a deeper reverence for faith. This was a sentiment captured well by author and outdoorsman W. C. Gray in his Musings by Campfire (1902):

“It has been my highly prized privilege to return to the Adamic conditions of existence, to live in the paradise of God, to taste the exquisite and exhilarating joys of primitive life. For delightsomeness there is nothing on the earth like it. To walk abroad free in the boundless and virgin forest, to listen to the solemn spiritual breathing of the pines, to be stirred with the melody of the woodthrush, and gladdened with the sight and sound of sparkling streams, to breathe the crystal air sweetened with the odors of the woods and spiced with the fragrance of balsam and birch—compared with this the highest artificial pleasures that wealth can furnish are a weariness. Adam was under disadvantages, but after all he was the happiest man of his race. Let us return to Paradise. Let us forsake the vapid follies of fashion and display and dissipation, and return to a life as simple and unostentatious, as benevolent and unselfish, as that of our Lord.”

Organized camping for boys had begun emerging in the 1880s, and proliferated through the 1890s and early 20th century. Churches and YMCAs were behind the construction of many of the earliest permanent summer camps and year-round wilderness retreats, and the movement was given a boost by the advent of Scouting, which of course heartily joined in the camp building and celebration of outdoor living.

The Creation of Christian Brotherhoods

“No church today is fully alive to its mission that has not in connection with it some kind of men’s organization, call it Club, League, Brotherhood, or what you will.” –William Scott, “Men in the Church” (1909)

When it came to winning the allegiance of men in the 19th century, churches had several competitors, from secular sports and entertainment to the simple saloon. But their main rival was fraternal lodges. From the well-known Freemasons and Odd Fellows, to once robust but now nearly defunct organizations like The Improved Order of Red Men, fraternal lodges were hugely popular in the latter third of the 1800s — a period which has been dubbed “The Golden Age of Fraternalism.”

Given the cultural context we’ve explored in this series, it’s not hard to understand why. The “Cult of Domesticity” which charged women with making home a heaven on earth had turned a man’s abode into a sanctified, doily-filled, female-friendly sanctuary, where the family patriarch had to watch his p’s and q’s and be on his best behavior. Men of this period, who were already disinclined to spend time with wife and family, thus looked for other, exclusively male refuges of sociality. Boys weren’t the only ones who craved the company of a gang; grown men did too.

Finding that gang at church wasn’t an option, since they were dominated by the same feminine ethos that prevailed at home. That left saloons, and lodges.

As Putney explains, according to research done in 1906 by Carl Case, a Baptist minister with a PhD from the University of Chicago, “as things stood, the social needs and spiritual aspirations of men were much better served by the lodge than by the church”:

“Churches forced men to listen to ministers whom they might not respect; lodges offered men the chance to talk freely, and on timely subjects. Churches assigned men committee work that belittles their manhood; lodges undertook ‘weighty’ charity work and assigned men to ‘important’ positions. Church religion was too otherworldly and feminized; lodge religion was ‘practical’ and fit ‘the legitimate demands of a man’s religious nature.’”

At church, men were told they were “broken” and ought to be more like their angelic wives, whose purity men needed in order to cleanse their degenerate natures. At the lodge, men were treated like morally autonomous beings, carriers of distinct virtues that were praised and respected; maleness wasn’t an obstacle to redemption, but a prerequisite. At church, at least many Protestant churches, there weren’t opportunities to participate in rituals, which for thousands of years functioned as one of men’s primary methods of communication, education, and fellowship. At the lodge, rituals provided members with tangible symbols of belonging and progress.

Most of all, the lodge provided men a way to socialize as they had since the beginning of time: as part of all-male gangs. Rather than being guilted into spending more time with his family, as he was at church, a man’s fraternal brothers supported him, and made him feel he was right where he belonged.

For muscular Christians, the fact that fraternal orders were beating churches at attracting men didn’t mean that all hope was lost; churches just needed to become more lodge-like than lodges. As Case optimistically concluded:

“If the lodge satisfies men, the church can do it. It can be a home of enjoyment, a means of fellowship and sociability, a place of activity, discussion, and responsibility, a satisfaction to the religious nature, far better than the lodge.”

To this end, there arose a so-called “Brotherhood movement” in which churches began special clubs, Bible studies, and fraternities exclusively for men.

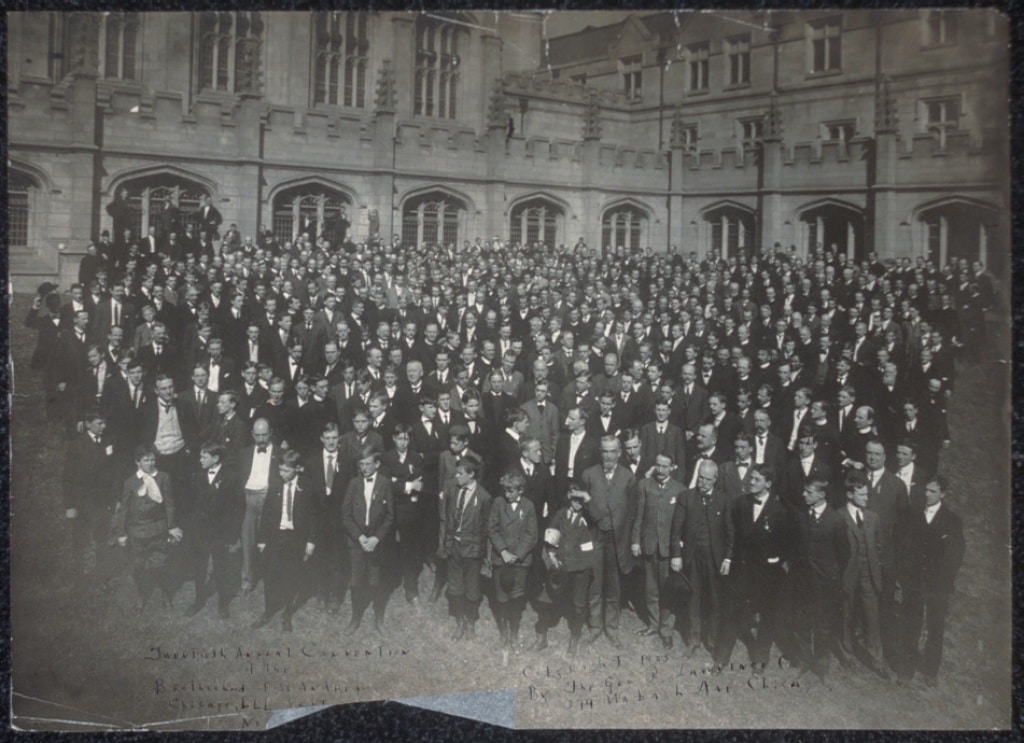

“The first church men’s club to achieve national prominence,” Putney reports, “was the Brotherhood of St. Andrew.” Founded in 1883, the Episcopalian organization evinced a martial ethos, with leaders referred to as “lieutenants” and rank and file members as “privates.” According to Putney, the function of the group was largely to encourage members to live up to the two pledges made at initiation: “to pray daily ‘for the spread of Christ’s Kingdom among young men’ and to bring at least one male friend per week to church or Bible study.” Members rose to the challenge and all those invitations added up; by 1903, the Brotherhood of St. Andrew had recruited 9,000 members. Exulted the group’s Chicago chapter:

“Our seats are full, and any Sunday morning may be seen forty to fifty men sitting together in a solid phalanx, four or five to a pew, worshipping God and singing His praise, shoulder to shoulder.”

Other clubs soon arose with the same kind of “military”-like structure and mission, including the Brotherhood of Andrew and Philip which was interdenominational and grew from its founding in 1888 to boast 25,000 members by 1903, and the Brotherhood of St. Paul which was for Methodist men and eventually attracted 25,000 members as well. The Brotherhood of St. Paul was distinct from other Protestant clubs in that it developed elaborate, Masonic-like initiation rituals, as well as orders through which members could advance. Another Mason-esque feature was the formation of a “mutual benefit society,” a kind of insurance fund for members that was common to non-church-affiliated fraternal lodges.

As boys often found church as dull as their fathers, many of these Brotherhoods founded “junior orders” for the younger set, and these church-related boys’ clubs came to number around forty-four by 1911.

Catholics participated in this “Brotherhood Movement” as well. Muscular Christianity had far more of an influence and following in Protestant churches than in Catholic ones, mainly for the reason that the gender gap seemingly existed far more severely amongst the former, than the latter, if it existed at the time for Catholicism at all (though it does now). Why was this?

Scholars speculate that because Catholic immigrants tended to take hard, blue collar jobs, requiring strength and plenty of physical exertion, the 19th century’s “masculinity crisis” did not resonate with them the way it did the Protestant middle class. At the same time, the Church was buffered from concerns about the feminization of Christianity by its ironclad hierarchy of all-male clergy, and the existence of masculine, even martial strongholds of non-sentimental disciples of Christ, such as the Society of Jesus.

Nevertheless, Jesuit communities at the Catholic-founded universities of Fordham and Xavier did develop a philosophy in the 1890s that stressed the importance of athleticism, and could be termed “Muscular Catholicism.” Catholics were active in the Social Gospel movement and founded several of their own fraternal orders and clubs as well.

Barred from joining the Masons by decree of the pope, Father Michael J. McGivney founded a fraternal order for Catholics in 1882. The Knights of Columbus served as a mutual benefit society, social club, service organization, and source of American-Catholic pride. By 1909, the Order had grown to encompass 1,300 councils and 230,000 knights.

In addition to the Young Men’s Institute, some dioceses sponsored divisions of the Catholic Youth Organization (C.Y.O.), which offered athletic programs designed to develop participants’ sportsmanship and Christ-like character.

The Catholic Order of Foresters was another fraternal society somewhat patterned after the Masons, and the Church also spawned several all-male temperance societies such as the Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America; Putney notes that “despite its name,” the organization “was a rather convivial group, with buildings containing gymnasiums, reading rooms, and billiard halls,” and it attracted 25,000 members from 10 states. There was even a Catholic version of the YMCA; with 12,000 members around the turn of the century, the “Young Men’s Institute” operated on a much smaller scale than the organization on which it was modeled.

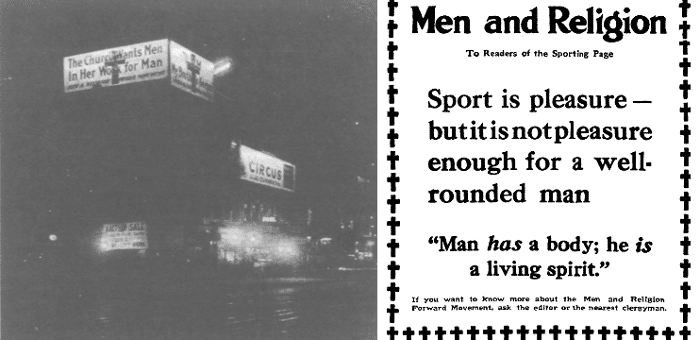

The Men and Religion Forward Movement

One last organization is worth mentioning before we move on. Though it was short-lived and doesn’t exactly fit amongst the clubs and fraternities mentioned above, it emerged from their success, and is also notable, Putney, observes, for being “the only countrywide religious revival in America ever to exclude women.”

The idea behind the “Men and Religion Forward Movement” was for individual church fraternities, clubs, and YMCA branches to join forces in advancing the principles of Muscular Christianity nationwide.

At a meeting held in New York in 1910, representatives from the Y, the International Sunday-School Association, and various church clubs and fraternities from around the country, came up with the “Buffalo Resolutions,” which, as Putney relates, laid out a “‘five-fold method of attack’: boys’ work, Bible study, missions, individual evangelism, and social service.” The movement’s official motto was to be “More religion for men, and more men for religion,” and its overarching goal was to evangelize men across the country — “to help find the 3,000,000 men missing from participation in church life — while affirming a rigorous, masculine approach to the faith and emphasizing “the heroic and aggressive in Christianity.” As a backer of MRFM explained, their movement differed from traditional revivals in that they wouldn’t be coed, nor emphasize the production of emotional experiences in order to effect conversion:

“There will not be a trace of emotionalism or sensationalism in this entire campaign. The gospel of Jesus of Nazareth — and its practical application to our practical daily life — is presented calmly, sanely, logically, so that it will convince the average man, who is a man of sane, logical, common sense. Women have no part in this movement, the reason being that Mr. Smith [MRFM’s first in command] believes that the manly gospel of Christ should he presented to men by men.”

The eschewing of emotion and the exclusion of women from the revival weren’t the only things that made the Men and Religion Forward Movement unique; it is also strove to utilize the latest techniques in business and advertising in order to share the “greatest story every told.”

The proponents of the MRFM were frustrated that most churches remained entrenched in old-fashioned tradition and hadn’t adopted the modern techniques of the marketplace to effectively and efficiently “sell” men on the faith. This refusal to move beyond “antiquated methods,” an ad executive opined, amounted to “sacred stupidity.”

In contrast, the Men and Religion Forward Movement would be run with all the efficiency and professional strategizing common to any other modern advertising campaign; as an article in Collier’s magazine put it, the backers of the MRFM wanted to approach the evangelization of men with the same kind of “fervor and publicity skill which a gang of salesman would apply to soap that floats or suits that wear.”

The MRFM advertised its revivals on billboards and in ads placed in newspapers and in men’s magazines.

A committee of ninety-seven of the MRFM’s top leaders enlisted one hundred of the “strongest” men in each of the seventy-six U.S. and Canadian cities the traveling revival was to visit to serve as a kind of “street team,” recruiting and exciting potential attendees, and preparing the location for the event. Questionnaires were sent to these reps to refine the campaign’s approach to each city; graphs and charts were constructed; data was crunched; marketing experts were consulted. Advertisements placed in the cities’ newspapers and in men’s magazines got bigger and more colorful as the date of the revival approached.

Because of this groundwork, by the time the Men and Religion Forward Movement arrived, it invariably garnered a big turnout for its slate of parades, speakers, sermons, and altar calls. After more than a year of barnstorming around the country, and 7,000 male-only revival meetings, the MRFM had addressed 1.5 million men. Of these audiences, it converted on average one man per whistle-stop, a significantly smaller “harvest” than the movement had been hoping to reap. The Men and Religion Forward Movement’s organizers ultimately disbanded, and its first year of existence was also its last.

[aesop_chapter title=”Part IV: Muscular Christianity” subtitle=”Effects, Ends, and Embers” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads//2016/09/fire.png” bgcolor=”#888888″]

So, did it work? Were the combined efforts of Muscular Christians successful in closing the gender gap between men’s and women’s commitment to the faith?

The effect of the Muscular Christianity movement on the overall sex ratio of U.S. churches was notable, but modest; Putney reports that “the proportion of men in the Protestant churches increased only 6.4 percent between 1906 and 1926 (going from 39.3 percent male to 41.8 percent male, according to U.S. census figures).”

Muscular Christianity may not have significantly moved the gauge on the gender gap of the faith as a whole. But as Putney further found, the uptick was actually more robust when one looks just at the middle and upper class denominations the movement targeted the most:

“Those denominations included the Congregational Church (where the proportion of men grew by 10.9 percent between 1906 and 1926), the Northern Presbyterian Church (where male membership increased by 11.2 percent between 1906 and 1926) and the Episcopal Church (where the proportion of men grew by an impressive 20.8 percent between 1906 and 1926).”

Thus, while it didn’t achieve the gender parity in church membership it strove for, it seems that the Muscular Christianity movement did have a fairly significant impact in attracting more men to certain outposts within Christendom.

Additionally, “butts in pews” was not the only goal of Muscular Christianity — its aim was also simply to inject greater virility into the faith’s overall ethos. Here it did score some successes — creating new, more virile hymns, manlier artistic depictions of Christ, and dozens of all-male brotherhoods.

As we’ll see, many of these changes lasted only as long as the movement’s heyday. But what’s really extraordinary about the influence of Muscular Christianity is actually not the effect it had on masculinizing the religion, but its broader impact on Christian and Western culture as a whole. In fact, had it not occurred, the landscape of modern life might look significantly different.

Muscular Christianity helped advance a cultural reverence for the wilderness, and develop the image of forests as natural cathedrals — woods as sanctuaries of spirituality. The movement spread the idea that the wild had a particularly salubrious effect on the young, spurring the creation of both church-sponsored and secular summer camps.

Muscular Christianity boosted the Social Gospel movement, shaping a lasting idea that churches should take an active role in supporting community charities and shaping politics.

The movement made common the idea that business principles and marketing strategies used to sell consumer goods, could, and should, also be applied to “selling” the gospel — an idea modern megachurches have taken and run with.

By far the biggest impact of Muscular Christianity, of course, has to do with the way it shifted societal perceptions of physicality. It diminished the old Platonic/Augustinian body/soul dualism, bringing about what historian T.J. Jackson Lears called a “fundamental reorientation” in Western citizens’ view of the self. The movement not only turned formerly resistant churches into champions of exercise and sports, but advanced the popularity of athletics and physical culture throughout society as a whole. It played a fundamental role in the proliferation of gymnasiums, and their transformation into one of America’s most important “third spaces.”

The effect of Muscular Christianity on Western culture was indeed profound. But it turned out to be a double-edged sword, for its outsized influence ultimately sewed the seeds of its own demise.

Why Muscular Christianity Lost Its Strength

After four decades of influencing the cultural zeitgeist, Muscular Christianity’s vim and vigor finally fizzled out in the 1920s. Several reasons were behind the atrophying of its vitality.

With its emphasis on manly strength and forceful, martial virtue, Muscular Christianity was uniquely well aligned with American culture at the start of WWI. And indeed, many of its adherents were boosters for involvement in the war, and organizations like the YMCA played a prominent role in offering service to troops during the conflict.

Yet if the movement was uniquely well-positioned at the beginning of the war, it was also uniquely well-positioned to bear the brunt of the cultural shift which occurred in its wake.

The aftermath of WWI extinguished much of the energetic idealism of the previous decades, and replaced it with disillusionment and cynicism. There wasn’t much societal appetite for talk of keeping one’s body in fighting shape, nor of the celebration of masculine, battle-related virtues like courage or honor. Notions of Christian chivalry got significantly muddied in the trenches.

The purpose of the war may have been ambiguous, but the sacrifices made were not. The cycle in which a societal concern about the health of manhood rises during peacetime, and then fades following its demonstration on the battlefield, had turned round once again, moving from the former phase to the latter.

Men didn’t feel the need to prove themselves, and people didn’t want to reform society or live the strenuous life. They just wanted a “return to normalcy”; to let their hair down a little; to enjoy newly accessible technologies like the radio and the automobile; to indulge in vices. They weren’t in the mood for more sacrifice, either for country or for God, and the Christian faith as a whole lost traction in American culture.

Science was seen as a better source of principles with which to guide society, over the kind of subjective idealism that had seemingly led the world into bloody conflict. The field of psychology particularly emerged as a replacement for the answer-finding, behavior-informing, life-directing authority which had formerly been the purview of religion. The burgeoning world of business also provided new kinds of goals by which a man could orient his life; his highest aspiration became the corner office, rather than a mansion in heaven.

This increasing secularism affected all of the institutions muscular Christians had originally established on a foundation of faith.

By the 1920s, the Boy Scouts of America had begun to downplay the organization’s connection to religion, sanctioning boys hiking on Sunday instead of going to church, and pushing to reduce the number of scoutmasters who were also clergymen. While a third of scoutmasters had been ministers in 1912, only 10% were by 1925.

In 1931, the YMCA dropped its requirement that members belong to an evangelical church, and began to downplay their Bible studies and missionary outreach. The Y’s mission instead shifted to promoting a culture of good character and wellness, only tangentially informed by Christian principles.