This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction-free book to read offline at your leisure. Available as an ebook or a paperback.

In our previous article in this series on the history of depression, we saw that its origins have alternatively been chalked up to a number of theories: excess of “black bile” in the body, the sin of sloth, wrong thinking, enervating luxury, conflicts in the subconscious, and a biological imbalance in the brain. Some of those ideas are still with us, only in a different form, and refined according to the latest research. Today we’ll take a look at the various modern hypotheses as to what makes someone vulnerable to depression and precipitates the arrival of the black dog.

Genetics

It’s hard to say exactly how large an influence genetics has on depression, but scientists are certain it does play a part. Their confidence in this stems from studies done on identical and fraternal twins that were separated at birth. Because identical twins share identical DNA, watching how they develop in different environments allows researchers to see how much genetics influence everything from heart disease to religiosity and, yes, even depression. Studies suggest that, on average, if one identical twin becomes depressed, the other will also develop depression 67% of the time, no matter their respective life experiences or family upbringing.

Compare that to fraternal twins separated at birth. Unlike identical twins, fraternal twins usually only share about 50% of their DNA. Studies on fraternal twins separated at birth show that, on average, if one twin develops depression, the other suffers a bout of it 19% of the time.

This difference between the incidence of depression amongst identical and fraternal twins clearly points towards there being a genetic component to the condition.

But it needs to be emphasized: DNA plays just one role. Remember, only 67% of identical twins both developed depression, suggesting that factors like upbringing, life experience, and thinking styles can and do affect a person’s vulnerability to being melancholic.

So what genes specifically cause depression? A few culprits have been proposed over the years, the most notable one being the 5-HTT gene. A 2003 study found that individuals with two short alleles of the 5-HTT gene had a more anxious or “neurotic” temperament and had a greater chance of becoming depressed after a stressful event than individuals with two long alleles. However, a study in 2009 found no connection between the 5-HTT gene and depression.

What’s likely is that there isn’t a gene or genes responsible for depression per se. Rather, depression may result from multiple genes working together in complex ways. So too, genes that give someone a more anxious temperament may not directly cause depression, but can instead make someone more sensitive to stress, which, if not managed correctly, can ultimately lead to deep depression.

Bottom line: researchers know that genetics influence one’s susceptibility to depression, but can’t really say how much. And, according to many researchers, they probably never will; DNA is just one factor that’s intimately intertwined with many others.

Brain Chemistry

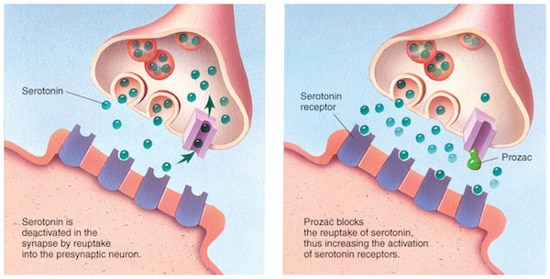

For the past thirty years or so, depression has often been labeled as a mental disease caused by a “chemical imbalance” in the brain. Curing depression, the thinking has gone, is simply a matter of swallowing a pill that’ll bring things back into harmony.

Those chemicals that are supposedly out of whack are neurotransmitters — tiny little chemicals that communicate information between neurons in your brain. Researchers theorize that a few neurotransmitters are involved in causing depression, the two biggest being dopamine and serotonin.

Any time you feel motivated to do something, to achieve some sort of reward, you can thank the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine is what gives us our drive to seek out food, shelter, and sex. Dopamine also motivates us to pursue new things and experiences of all kinds, and we get a hit of it when we’re doing everything from summiting a mountain to playing video games to even simply checking our email. Research suggests that individuals with depression have lower amounts of dopamine in their brain or have blunted dopamine sensitivity compared to non-depressed individuals. Low dopamine or low dopamine sensitivity likely plays a part in why those suffering from depression don’t feel motivated to do anything, even simply getting out of bed.

While the brain imbalance theory of depression made for a clear and graspable narrative of its cause, its current premises are being questioned.

The other neurotransmitter that has gotten the lion’s share of attention in relation to depression is serotonin. Serotonin helps regulate appetite and sex drive, as well as one’s mood. For the past thirty years, researchers, psychiatrists, and therapists have posited that low amounts of serotonin in the brain was one of the primary drivers of depression. Consequently, the biggest anti-depressants on the market are designed to boost this neurotransmitter.

But, recent research has shown that serotonin might not have any effect on depression, and in fact, the effect may be the very opposite of what was once supposed. For example, when scientists in one study bred mice that didn’t have the ability to create serotonin at all and then ran them through a series of behavioral tests, the mice didn’t show any signs of depression (yes, mice can get depressed), though they did get a bit more aggressive. A more damning study found that individuals with increased levels of serotonin activity were more likely to be depressed than individuals with normal levels. In other words, instead of too little serotonin being the cause of depression, the issue may actually be too much of it.

Hormones

Neurotransmitters aren’t the only chemicals that may play a role in depression; hormones could have an impact as well. For example, individuals with lower levels of testosterone have been found to have an increased risk for depression. This may partly explain why women are more likely to get depressed than men and why men who undergo testosterone replacement therapy sometimes report a boost in their mood. Scientists believe that testosterone levels spur dopamine production, which in turn elevates mood.

Major Negative Life-Changing Events

Negative life events like job loss, divorce, and the diagnosis of a serious disease can all lead to a period of melancholy. While feeling low after experiencing such misfortunes might seem to be a normal response rather than a disorder, the DSM classifies all post-negative-life-event sadness (that meets criteria we’ll talk about in the next post) as depression, unless it results from the death of a friend or family member (in which case it’s “normal” grief, and not depression). When the latest DSM was created, there was a debate about including grief as a mental disorder as well, but it was ultimately left out.

Chronic Stress

Chronic stress makes an individual’s body and mind more vulnerable to depression in several ways.

While a little stress every now and then is good for you, too much of it can have disastrously ill effects on your body and mind, including a greater vulnerability to depression.

When you experience stress, your body’s level of cortisol ratchets up. The burst of this hormone facilitates your brain’s dopamine production, which in turn urges you to take action to alleviate the stress. That’s great if the stress comes in short, periodic bursts; the stress response is what drives you to ace a test, win a race, or even save your own life. It becomes a problem, however, when the stress becomes prolonged. When you have too much cortisol for too long, dopamine becomes depleted rather than elevated; chronic stress essentially “breaks” your dopamine system. In the absence of that motivating neurotransmitter, you start feeling lethargic, emotionally dulled, and unmotivated to do anything — hallmarks of depression.

In addition to altering one’s neurotransmitters and hormones, chronic stress can physically change parts of the brain. Excessive and prolonged cortisol exposure shrinks the hippocampus, which some research suggests may make a person more vulnerable to depression. At the same time, cortisol enlarges the amygdala, which makes individuals much more sensitive to negative emotional stimuli — like sad news stories or daily frustrations — and less responsive to positive emotional stimuli — like getting a raise or even seeing a smiling face. The result is a person who is hyper-attuned to the negative in life, which can lead to more anxiety, and ultimately a plunge into depression.

Chronic stress may be more of a depression trigger for men than for women. Research suggests that when women encounter stressful situations, their bodies release more oxytocin, which motivates them to reach out to others. Researchers call this the “tend and befriend” stress response. Social engagement may offset and help women alleviate the negative emotions that come with stressful events. Men, on the other hand, don’t release as much oxytocin during negative and threatening experiences, and tend to react with the “fight or flight” response. Constantly feeling driven to attack or run away from stressors can wear down a man’s mind and put him at risk for depression.

Faulty Cognition

Practitioners of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) argue that depression is largely caused by negative thoughts and behavior. A tendency towards pessimistic beliefs, rumination, catastrophizing, me-always-everything thinking, and obliviousness to the positive, CBT therapists argue, can lead to a detrimentally melancholic mindset. Eliminating depression, then, is largely a matter of challenging and changing those negative thought patterns.

While it’s true that pessimistic and negative thinking patterns are associated with low mood, it’s hard to say with certainty whether it’s the negative thinking that causes low mood or if it’s the low mood that causes negative thinking. It’s more likely that thoughts and emotions are connected in a feedback loop and that they both influence and feed into each other.

Evolution

This is one of the more intriguing (and controversial) theories of the origins of depression. Several evolutionary psychologists argue that depression may actually have an adaptive or evolutionary purpose.

At first blush, that probably seems paradoxical. How can something that makes you feel like crap, and leaves you unmotivated and possibly suicidal, provide an evolutionary advantage?

The theory goes that our various moods — happy, sad, angry, anxious — are signals that evolved over hundreds of thousands of years to spur behavior that moves us towards fulfilling primary evolutionary purposes like reproduction and survival. Anxiety made our caveman ancestors more vigilant to their surroundings, so they could ward off attacks from predators or neighboring tribes; anger instigated action to stamp out an existential threat; and happiness inspired a more curious and open-minded approach to new ideas and experiences, like trying new foods or exploring new territory.

But what about a melancholic mood? How might a gloomy mindset have aided in survival? Well, there are a few hypotheses as to the answer. A low mood may be nature’s way of telling humans (and other mammals) to change a self-defeating behavior, or to retreat from an effort that could ultimately be dangerous or wasteful. In some instances, it may have been advantageous for our caveman ancestors to give up, to go home to mope a bit, and to live to fight another day.

Another theory is that low mood, and the lethargy and un-motivation that comes with depression, provided a survival advantage by keeping animals and our caveman ancestors close to home when the environment was becoming increasingly threatening. Some researchers believe this explains things like “seasonal affective disorder”; we might just get down in the dumps during the winter because the cold, grey, sunless skies signal our pre-historic brains that going out would be fruitless and possibly dangerous, and that staying close to home and preserving energy would be a better survival strategy.

A melancholic mindset may also have spurred our caveman ancestors to lay low near the home-cave and analyze how to respond to a survival or reproductive problem. Perhaps Joe Q. Caveman faced a bison shortage or was constantly rebuffed by the local cavewomen. The low mood that came in response to these problems may have helped Joe reflect on the issue at hand and figure out what to do.

While these theories might seem questionable, evolutionary psychologists bolster their argument by pointing to studies that show that people with low moods are better at analyzing their environment. Researchers call this heightened ability “depressive realism.” In a classic study, researchers had participants press a button and rate the control they perceived they had over whether or not a light came on. The participants didn’t actually have any control over the light, and depressed individuals caught on to this fact more quickly than their upbeat counterparts.

Another way a low mood primes us for analysis is that it causes us to really think hard about our problems. A common symptom of depression is rumination, or constantly thinking about a problem over and over again. Excessive rumination — especially if it only centers on the nature of your mood and emotions — can simply lead to deeper despondency, and for this reason therapists often try to get their patients to cut it out. But there may be a benefit to it as well. Several studies have shown that focused rumination can break down complex problems into smaller components so that they’re more approachable. The melancholic’s social isolation and lack of interest in other activities aid this process, and drive a person to concentrate on a problem until they crack the nut.

Thus, depression may (if harnessed and directed) actually have some benefits, and its cause may be a primitive brain that’s trying to help us survive and better navigate a threatening landscape. Unfortunately, the environment of our modern world has hijacked this potentially advantageous response, and turned it into something that merely sickens us.

A Mismatch Between Modern Life and Our Ancient Brains

The way we live now is very different from how we lived for thousands of years. Increasing rates of depression may be a result of this mismatch.

“Why is it that in a nation that has more money, more power, more records, more books, and more education, that depression should be so much more prevalent than it was when the nation was less prosperous and less powerful?” –Dr. Martin Seligman, Learned Optimism

Mood scientists suggest that the evolutionary origin of depression may explain why rates of it have increased tenfold in the last 100 years. Our bodies, minds, and mood systems evolved for an environment that no longer exists today, and this mismatch is likely making more and more people feel miserable.

Evidence of this theory can be found in the fact that depression is extremely rare in communities and tribes that live similarly to our primitive ancestors. Dr. Stephen Ilardi, clinical psychologist at the University of Kansas and author of The Depression Cure, notes that, “researchers have assessed modern-day hunter-gatherer bands — such as the Kaluli people of the New Guinea highlands — for the presence of mental illness, and they found that clinical depression is almost completely nonexistent among such groups.”

The reason depression is so rare, llardi argues, is that peoples like the Kaluli live a lifestyle that’s congruent with their evolved biology and psychology; their way of life essentially acts as a natural antidepressant. Says Ilardi: “They’re too busy to sit around brooding. They get lots of physical activity and sunlight. Their diet is rich in omega-3, their level of social connection is extraordinary, and they regularly have as much as 10 hours of sleep.”

In contrast, modern folk are sleep-deprived, sedentary, and rarely venture outside their fluorescent-lit cubicles. Crucially, we people of the 21st century are also highly isolated. Ancient tribesmen were part of close-knit communities; today we exist as fragmented individuals who often must bear life’s disappointments and setbacks on our own. In our lonely echo chambers, with our primary focus on the self, waves of melancholy become magnified many times over.

Unreasonable Expectations of Happiness and Comfort

Modern culture is dominated by what psychologists Todd Kashdan and Robert Biswas-Diener call “smiling fascism,” in which if you don’t feel happy 24/7, something is wrong with you.

Another possible reason for the uptick in depression is that we really aren’t suffering from it more, but that we simply think we are because we’ve set the bar so high as to what it means to be happy. And what begins as what would have, in an earlier age, been considered a passing bout of mere unhappiness, can then lead to the real article.

If you haven’t noticed, modern culture places an inordinate amount of emphasis on bliss and comfort. There are thousands of books and blog posts out there on how to hack your happiness, and the subtle message is often this: if you’re not perennially chipper — and living your best life now! — then something is wrong with you. In their book, The Upside of Your Dark Side, psychologists Todd Kashdan and Robert Biswas-Diener call today’s overemphasis on happiness a “smiling fascism.” And this push to march in lock-step with the beat of an ever up-tempo drum might actually be making us feel more miserable and depressed.

Research has shown that if you make happiness your goal, you’re less likely to be happy. There are a few reasons for this. For starters, cultural expectations of what happiness looks like are typically unrealistic. Happiness, as it is currently defined, is a fleeting feeling that comes and goes. Being downright giddy all the time is impossible for most people. So when they set the goal of being constantly happy, they fail, which makes them feel disappointed and deficient. The repetition of this cycle can lead to a prolonged funk.

The other reason making happiness your goal can actually backfire is that we’re really bad at knowing what will make us happy in the long-term. Kashdan and Biswas-Diener call this the “time travelers” problem. When we set a goal that we think will make us happy in the future, we do so from the view of our current self. But the problem is we change over time and that goal might not make our future-self all that happy.

At the same time that we’ve raised our standard as to what it means to be happy, we’ve also increased our expectations in regards to comfort and ease. Fast internet, comfortable beds, climate-controlled rooms, and smooth and painless customer service aren’t just luxuries anymore, but self-evident human rights.

But the desire, nay, demand, to live a frictionless life may be setting us up for crippling anxiety and depression. As comfort in a society increases, its tolerance for discomfort decreases. This is true not only in regards to inconveniences we encounter in the external world, but for the darker feelings that happen within us as well. As we discussed in our post about the history of depression, sadness was once seen as just a natural part of the ebb and flow of life. So too, a gloomy mindset was just one of several temperaments people were born with, each with their unique advantages and drawbacks. Fast forward to today, where we view feelings like sadness, anger, and guilt as negative because they make us feel bad, and we experience them as a deviation from what we should be feeling. Instead of learning how to live with our more challenging emotions, we label them as psychologically abnormal and do what we can to root them out. When we’re unsuccessful in doing so completely, the gap between our high expectations and the reality of our stubbornly melancholic temperament can make us feel frustrated and even more miserable than before.

Thus, in not being comfortable with being uncomfortable, we’ve fragilized our psyches and made ourselves more susceptible to the very emotions we wanted to avoid in the first place.

Conclusion

So what causes depression? Well, after thousands of years of theorizing, and tons of modern research, the short answer is: we still don’t really know.

Depression is complex. While it’s tempting to point to one specific cause, the reality is that depression is the result of several factors intermixing in ways that are nearly impossible to untangle. Because the causes of depression are so complex and varied, we may in fact never be able to precisely pin down its origins, especially on an individual, case-by-case basis.

In some ways this ambiguity is inherently frustrating, but in other ways it is freeing (you’re going to be seeing a common theme in the conclusions to these posts!). The healthiest approach to dealing with your depression may not be waiting for experts to tell you exactly what’s causing it, but to create a narrative of your own — based on sound reasoning — that leads you to take the most effective action.

For me, I’ve found it most helpful to view my depression through the framework presented by evolutionary psychology.

As with any evolutionary explanation for behavior, you always have to be skeptical of “just so” explanations. But I personally find the evolutionary theory intriguing because it provides some needed nuance to grappling with the black dog.

Instead of being completely bad and abnormal, depression becomes a mood state that’s quite natural and has both costs and benefits. The goal then becomes managing your low moods so you get the advantages while reducing and mitigating its drawbacks. Even the advocates of the evolutionary origin of depression will argue that past a certain point, low moods can become unhealthy and even-life threatening. When depression reaches this level of severity, it no longer has any benefits and everything should be tried to help alleviate it.

But for the folks who experience mild low moods throughout the year or who are in the depths of a deep (but not paralyzing) depression, a melancholic funk can act something like an early warning system. Writer Lee Stringer said this about depression: “Perhaps what we call depression isn’t really a disorder at all but, like physical pain, an alarm of sorts, alerting us that something is undoubtedly wrong; that perhaps it is time to stop, take a time-out, take as long as it takes, and attend to the unaddressed business of filling our souls.” I like that idea.

Whether the evolutionary theory of depression turns out to be accurate or not, the actions it prescribes to cure it are decidedly some of the most effective for leashing the black dog: living more like our forebearers by eating healthy, exercising, reducing stress, getting out in nature, belonging to an intimate community, etc.

Perhaps people who are predisposed to having a sunny disposition and engaging in beneficial behaviors don’t need the spur of depression to push them towards adopting a healthier lifestyle; if they fall off the good livin’ wagon, the results aren’t very dire. While for people like myself, who may be genetically inclined to anxiety and low moods, the first harbingers of depression are needed to serve as a wake up call to be more intentional about living in a natural, centered, vigor-inducing way. I know the realization that I’m prone to melancholy has made me much more proactive about seeking out best practices that will keep my inherent gloominess at arm’s length and prevent me from plunging into a deep depression.

That’s just my theory, of course. Add it to the growing pile of them, and pick out the narrative lens that most resonates with you, and, most importantly, motivates you towards actions that will keep your black dog at bay.

Read the Entire Series

My Struggle With Depression

The History of Depression

The Symptoms of Male Melancholy

How to Manage Depression

_____________________

Sources and Further Reading:

The Depths: The Evolutionary Origins of the Depression Epidemic

On Depression: Drugs, Diagnosis, and Despair in the Modern World

Undoing Depression: What Therapy Doesn’t Teach and Medication Can’t Give You

The Depression Cure

The Upside of Your Darkside

Rewire Your Brain: Think Your Way to a Better Life