Of the short stories Jack London penned, “In a Far Country” is my favorite.

The story follows two characters London calls “The Incapables” who travel to the savage and unforgiving Alaskan North searching for gold and adventure.

The men make a very poor go of things: they bicker, shirk chores, hoard food, take pleasure in each other’s suffering, and ultimately come to a bad end.

The Incapables’ most glaring problem was that they lacked what London called “true comradeship.” At the beginning of “In a Far Country,” London describes the quality as part of the overall shift a man must make if he is to successfully be part of a wilderness expedition:

his pinch will come in learning properly to shape his mind’s attitude toward all things, and especially toward his fellow man. For the courtesies of ordinary life, he must substitute unselfishness, forbearance, and tolerance. Thus, and thus only, can he gain that pearl of great price — true comradeship. He must not say ‘Thank you’; he must mean it without opening his mouth, and prove it by responding in kind. In short, he must substitute the deed for the word, the spirit for the letter.

For London, true comradeship is when you put the interests of a unit to which you belong before your own selfish interests. You do what you can so you’re not a burden on those around you. You “carry your own pack,” as Theodore Roosevelt put it.

It goes beyond that, though.

True comrades have each other’s backs. If one man in the group falters, the others help him up and stand in the gap. In turn, when that man again finds his footing, he turns around and reciprocates: he sees what he can contribute to the team; he doesn’t just express his gratitude in word, but in deed.

Males band together to accomplish some purpose or mission, whether that’s carrying out a military operation, winning a game, executing a campout, or removing a neighbor’s tree stump. And whenever males band together, camaraderie manifests itself; the extent to which it develops determines both how much the men enjoy being part of the group, and the group’s success in their endeavor. True comradeship represents a “pearl of great price” because it’s what makes a group hum; it’s the esprit de corps that overcomes obstacles and makes a team feel special, close-knit, bonded.

Given the importance of true comradeship in a group, males tend to have little tolerance for those who disregard its standards.

I think most (well-adjusted) men know there’s an unspoken rule that you don’t want to be the guy who acts as a stumbling block on a team. They’re honest about their capabilities; they step up when needed, and get out of the way when appropriate. They try not to be an annoying, grating chooch.

I also think most men aren’t a-holes. If they see a guy in their group who’s having a hard time, but who really wants to be part of the group and wants to help move the group forward, they’ll cut that guy some slack. They’ll offer encouragement, provide some one-on-one coaching, and/or find that man a place in the group that allows him to contribute without being a liability.

But when a dude fails to pull his weight, and demonstrates that he doesn’t care about the needs and purpose of the group, that guy is going to be resented by his comrades. And may ultimately be booted off the team.

I saw these dynamics in action when I played high school football.

Football is a team sport. Every guy on the field has an assignment, and if just one of those guys blows his assignment, it can blow an entire play, and in turn, the game. Success on the football field requires that an individual put the team’s interests before his own personal interests and ambitions.

For me, that meant I had to content myself with being a scrub during my freshman through junior years of my football career. I wasn’t a naturally talented athlete, so I didn’t get much playing time under the Friday night lights during my first three years of high school. Personally, it was disappointing, but I understood that it was what was best for the team. My getting on the field wouldn’t help us win.

Even though I wasn’t a starter, I did my best to live the principles of true comradeship. I found where I could contribute and that was on the scout team at practice. I did all I could to develop myself as a player, and I went hard at practice so that the varsity squad would get a “good look” for our upcoming game. I tried to show through deed that I was there for the team’s success. In return, the varsity squad showed their appreciation and respect. I never felt I was “less than” when I was a scrub.

In my senior year, I finally got to be a starter. And during the first few weeks of summer practice, I really witnessed the promise and perils of true comradeship play out.

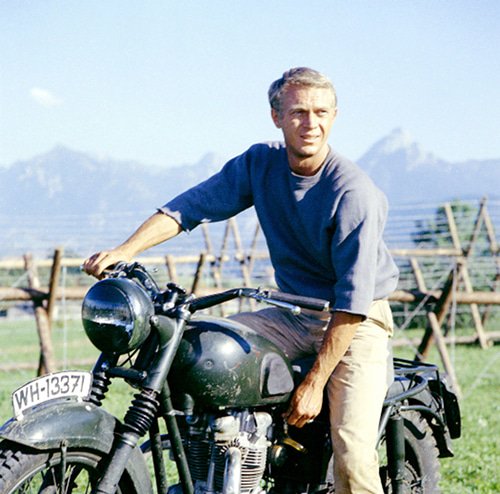

Two underclassmen came out for the team. I’ll call one guy Steve and the other guy Ed.

Steve wasn’t the best athlete, but he wasn’t terrible. When he applied himself and hustled, he could be pretty good. He wasn’t ready for varsity, but he had the potential to be a good scout team member to help the varsity get prepared for the games on Friday.

Ed was a big dude and really strong. But he was mentally slow. He went to special ed classes. Ed had a hard time picking up on plays and assignments. We’d have to explain things to him repeatedly before he’d get it. Even when things would seem to click, he’d forget what he’d learned. Ed would probably never be a starter, let alone get any playing time on varsity.

While Steve was mentally and physically more capable than Ed, Ed understood true comradeship while Steve didn’t. Consequently, things didn’t turn out well for Steve, but did for Ed.

When the football season starts in August, it’s hot in Oklahoma. Freaking hot. We’re talking temperatures in the high 90s to low 100s. So those first few weeks of practice are pretty unpleasant for everyone.

We linemen on the varsity squad noticed that Steve wasn’t volunteering very much to play on the scout team during practice. He’d just stand behind a mass of players on the sidelines, drinking water. When a guy on the scout team needed a break, Steve wouldn’t volunteer to sub in. He just hid and drank all the water. Steve was a liability.

Our first response to Steve’s sandbagging was to offer some friendly encouragement.

“Hey, man! You got this! Help us out here! We need you.”

Steve would begrudgingly get out onto the field, but then he’d half-ass it for a few plays and retreat to the sidelines as quickly as possible.

Always grabbing a water bottle on the way out. Natch.

This went on for a few weeks. We continued to kindly-but-firmly encourage Steve to help out. But our resentment towards Steve started to build. It was one thing not to practice. What really got our goat was that he drank all the water. We’d finish a drill and make our way to the water bottles only to find that they were empty because Steve had been nursing them while we were busting our butts.

On one particularly sweltering and humid day, we were running some plays. One of the defensive linemen on the scout team needed a break to get some water. He tapped Steve to go in because Steve hadn’t been in the entire practice. Steve demurred.

Our drill was being held up because of freaking Steve.

Finally, one of my fellow linemen had had it with Steve and his B.S.

This lineman walked over to Steve, pointed his finger at him, and yelled:

“If you’re not going to contribute to the team, then leave! We don’t want you here!”

Another lineman chimed in, “Yeah, dude! You’re drinking all of the water. We’re tired of it. Either start playing or get outta here!”

I joined the chorus. It was time for Steve to put up or shut up.

He shut up.

Steve ripped off his helmet and stormed off the field. He quit right then and there.

I remember feeling conflicted about the whole thing. It kind of felt like we bullied the kid off the team, but I don’t know how else the situation would have resolved itself. We gave Steve plenty of chances to show true comradeship, but he wouldn’t. It was in the team’s best interest (and maybe Steve’s, too) that he be given an ultimatum.

Contrast Steve with Ed.

As I said earlier, Ed had some developmental issues. We varsity linemen all understood that. We understood that Ed would need some extra help if he was going to be a part of the team. But what Ed lacked in talent and ability, he made up for in true comradeship. Ed contributed. He was the first to volunteer on the scout team at practice. When he was on the scout team, he went as hard as he could. He asked for help and coaching from his teammates. Ed made sure the varsity guys got water. At games, he was the loudest guy on the sideline. The dude was always trying to get everyone pumped up.

Ed was grateful to be part of the team, and showed it through his deeds.

He understood and lived true comradeship.

In return, Ed became one of our good friends. Not out of pity. He earned our respect. He was part of our crew. He’d come to the parties we’d have after games where we’d play NFL Blitz and eat Little Caesars pizza. If we heard that some a-hole was bullying Ed because of his disability, that a-hole got paid a visit by several big linemen. Ed was our dude. No one messed with Ed. We did our best to help Ed develop as a football player. We encouraged. We coached.

We were mutually edified in our relationship.

That’s what I think the fruit of true comradeship is. Mutual edification.

In my social relationships with men, it’s interesting to see who understands true comradeship and who doesn’t. The men who don’t usually have a hard time making and maintaining friendships. They also generally have a hard time in life. It’s because these guys are pretty contemptible — a quality that represents being both incompetent and annoying. They’re kind of living in their own world and oblivious to group dynamics. They’re more concerned about their own petty interests — how they’re looking, how they’re feeling, what they’re getting. Instead of contributing to the group, they just sow resentment and conflict.

How do you learn true comradeship?

I think developing it in boyhood is your best shot. I work with young men in different capacities, and I can see the boys who are grasping the idea of true comradeship and those who aren’t. The boys who don’t get it have a harder time socially. They think they’re the main character of life, and if something conflicts with that, they get all put out. On the flag football team I coach, these are the boys who want to play a certain position, even though they don’t have the aptitude to perform in that position in a way that would help the team, and even though they’re not willing to practice to gain that aptitude. Amongst the young men I lead at church, these are the boys who derail class discussions by shoehorning in whatever it is they want to talk about, no matter how unrelated, or complain that activities don’t align with their interests, and then, when an activity is planned which does, still don’t participate. These boys don’t think about how their actions either contribute to or detract from the experience of others, and their peers, who do, feel understandably resentful of that kind of attitude.

I’ve made it a point of having little chats with these boys about camaraderie and teamwork and the like. Some of them have started to catch on; most still haven’t taken the idea to heart. Hopefully, they’ll come to understand true comradeship one day. Because as the path to experiencing male bonding, feeling part of something bigger than yourself, accomplishing deeds you couldn’t do alone, and partaking of the riches of mutual edification, it’s truly a pearl of great price.

Be sure to listen to our podcast with Jack London scholar, Earle Labor. We discuss “In a Far Country” and London’s ideal of the Northland Code: