This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction free ebook to read offline at your leisure. Click here to buy.

Welcome back to our series on The Spartan Way, which seeks to illuminate the lessons the ancient Spartans can teach modern men – not in their details, but in the general principles that lie beneath, and can still be extracted and applied today.

“the Spartiates constituted a seigneurial class blessed with leisure and devoted to a common way of life centered on the fostering of certain manly virtues. They made music together, these Spartans. There was very little that they did alone. Together they sang and they danced, they worked out, they competed in sports, they boxed and wrestled, they hunted, they dined, they cracked jokes, and they took their repose. Theirs was a rough-and-tumble world, but it was not bereft of refinement and it was not characterized by an ethos of grim austerity, as some have supposed. Theirs was, in fact, a life of great privilege and pleasure enlivened by a spirit of rivalry as fierce as it was friendly. The manner in which they mixed music with gymnastic and fellowship with competition caused them to be credited with eudaιmonía—the happiness and success that everyone craved—and it made them the envy of Hellas.” –Paul Rahe, The Spartan Regime

No man wins any battle, of any kind, completely by himself, but rather requires a team of comrades. This truth was never so literally and viscerally brought to life than in the Spartan phalanx.

Spartan hoplites were distinguished by the heavy wooden shield they carried on their left arm; 15 pounds in weight, 3 feet in diameter, it was, Spartan scholar Paul Rahe notes, “an encumbrance more unwieldy and awkward than we are apt to imagine.” It was also nearly useless to a soldier fighting outside the phalanx; when facing the enemy, the shield “left the right half of [the soldier’s] body unprotected and exposed, and it extended beyond him to the left in a fashion of no use to him as a solo performer.” Thus “when infantrymen equipped in this fashion were operating on their own, cavalry, light-armed troops, and enemy hoplites in formation could easily make mincemeat of them.”

A hoplite’s shield was only effective when it was one of many employed in the phalanx formation. His shield protected the right half of the man to his left, while his neighbor’s shield protected the right half of his body. Phalanx warfare wasn’t about individual, Achilles-style glory. Each soldier critically needed the man next to him. Alone, each warrior was vulnerable and weak; together in the phalanx, their shields formed an interlocking wall of men that could defend against the blows of the enemy and push forward in strength.

Given this structure of mutual dependence, a phalanx was only as strong as its weakest link, and each man had to absolutely trust the brother next to him to give his all; if everyone held together, casualties were greatly minimized; if one man fell apart, he exposed everyone to greater danger. Unity and loyalty were thus paramount.

What motivated the Spartan warrior to refuse to be the weak link and to stand his ground in the heat of battle?

Shame was one powerful source of motivation. Shame has become something of a dirty word in modern times, but few forces more strongly compel behavior. A fear of shame is in fact only the necessary flip side of a love for honor; in an honor group, men not only strive for excellence but flee from disgrace. The Spartans cared deeply about maintaining the respect of their peers — their fellow equals; said Isocrates, they “think nothing as capable of inspiring terror as the prospect of being reproached by their fellow citizens.”

For a Spartan warrior to let down his brothers in combat would not only invite shame from his comrades, but humiliation from his entire community. As the Spartan poet Tyreatus writes, to return home a coward was the ultimate dishonor:

“Of those who dare to stand by one another and to march

Into the van where the fighting is hand to hand,

Rather few die, and they safeguard the host behind.

But for the men who are tremblers all virtue is lost.

No one can describe singly in words nor count the evils

That come to a man once he has suffered disgrace.”

While the fear of shame certainly played a powerful role in motivating a Spartan warrior to hold the line in battle, he was also driven by a still greater, and higher, force: love for his brothers-in-arms, who were also his friends and his family.

This love was developed from many of Lacedaemon’s unique institutions and traditions.

Partly it came from men growing up together in the agoge, and sharing both in its (oft-overlooked) pleasures and its famous hardships. Partly it came from the rule that all men under age 30 had to sleep at night in the barracks, rather than at home.

But arguably, the strongest force welding Spartan men together took the form of a tradition that lasted their whole life through: the syssitia — Lacedaemon’s fraternal, all-male messes. Gentlemen’s dinners.

The Syssitia and the Brotherhood Born From Breaking Bread

Once called andreia — literally “belonging to men” — the syssitia, Rahe explains, “was not just an arrangement for meals. It was an elite men’s club, a cult organization, and, at the same time, the basic unit in the Spartan army.”

At age 20, a Spartan man was required to join one of these dining clubs if he wished to become a member of the Homoioi. Each mess had about 15 members, and like modern fraternities, each likely had its own “character” — with certain associations to family lines, personality types, political and philosophical leanings, and so on. The recent agoge grad had to apply to the syssitia he wished to join, and its members would vote on his acceptance; the vote had to be unanimous — if one member blackballed the candidate, he was out. If you were accepted, you became a member for life.

Once a man had been accepted to a mess, he was required to dine at it each evening — not even kings could be absent without a worthy excuse.

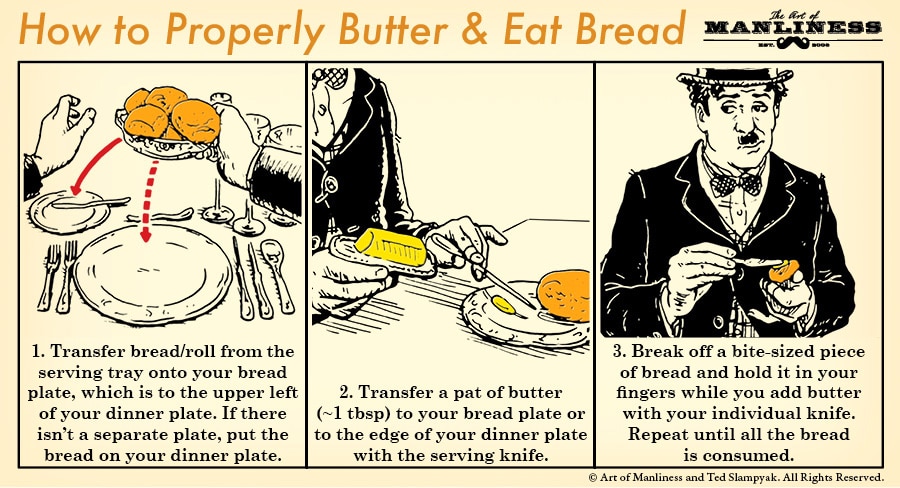

Each member of a dining club contributed to the mess’s stores that were used to make the nightly meal, repast which consisted primarily of a “black broth” made from pork, salt, vinegar, and blood.

As Nigel M. Kennell explains, however, “once the prescribed rations had been consumed,” the club’s members engaged in the “typically Greek propensity for competitive displays of generosity.” Members treated their messmates to foods that had to be, as the rules of the syssitia dictated, either raised/grown on their land or hunted themselves, and which could have included wild game, olives, fruits, vegetables, herbs, nuts, eggs, milk, cheese, butter, and wheat bread. “Before serving, the cooks announced the name of the day’s donor to his grateful companions so that they might appreciate his hunting prowess and diligence for them.”

Over this simple fare (and occasional delicacies), as well as the moderate drinking of wine (drunkenness was disdained), Spartan messmates spoke freely with one another about both civic and personal affairs. While Athenian men conversed publicly about politics and philosophy in the agora, Spartan men did so in private, amongst the comrades they respected and trusted, their daily banquets providing a confidential, comfortable sanctuary in which to hold such exchanges.

Men from many different ages and stages of life belonged to a mess, and the old mentored the young; as Kennell writes, the syssitia “bec[ame] at Sparta the preeminent medium for reinforcement of Sparta’s aristocratic warrior ethic.”

Syssitia conversations certainly weren’t all serious, however; Spartans themselves were hardly the somber and humorless drones we often picture them as. Lacedaemon was in fact one of only two Greek city-states to build a temple to the god of laughter. And according to Heraclides, Spartan youngsters were taught “Laconic” wit (more on this form of speech later) from an early age, seemingly to simply be better able to zing each other: “Immediately from childhood on they practice speaking tersely, then good-natured bantering back and forth.”

This affection for jesting continued through a Spartan man’s whole life and constituted an important part of syssitia culture; as Karl Otfried Müller wrote, “In common life, laughter and ridicule were not unfrequent at the public tables; to be able to endure ridicule was considered the mark of a Lacedæmonian spirit.”

Good-natured ribbing has long formed much of the unique camaraderie that exists between men, as such teasing (which includes the giving of nicknames) constitutes a paradoxical way of demonstrating the solidity of their bonds. Men will swap insults to toughen each other up, while testing and strengthening the relationship; if you can trade good-natured barbs, without the parties being offended, it indicates a significant level of trust.

At the same time, some gallows humor helped the Spartans deal with the weightier aspects of their martial vocation. As Edith Hall observes in Introducing the Ancient Greeks: “It is easier to practice psychological honesty about dark aspects of human existence with the protective shield of laughter . . . [the Spartans] used pointed Laconic wit to help maintain the morale of their warrior culture.”

After eating, talking, and joking, the men would raise the paean, singing together as a group, and then each singing some of the verses of Tyrtaeus in turn.

The camaraderie built through sharing nightly meals in their dining clubs ultimately proved an advantage for the Spartans in combat — helping to create the unity so crucial for success in phalanx warfare. As Thomas Arnold wrote, “The object of the common tables was to promote a social and brotherly feeling amongst those who met at them; and especially with a view to their becoming more confident in each other, so that in the day of battle they might stand more firmly together, and abide by one another to the death.”

But the syssitia’s benefit was hardly limited to war; it served as a lifelong source of friendship and support in peace as well.

Indeed, the Spartan dining clubs were also known as pheiditia — a term likely derived from philitia, or “love-feast.”

Be sure to listen to our podcast with Paul Rahe all about Sparta: