Men today aren’t joiners. They’re disillusioned and cynical about society’s organizations. Politics? Riddled with corruption. Corporations? Run by greedy bastards. Church? Brimming with hypocrites. Fraternal lodges? Just a bunch of old fogies. Men in contemporary society prefer to remain aloof and apathetic, criticizing these organizations from the outside. For many men, manliness has been equated with rugged individuality; the man who does his own thing and associates as little as possible with other people. So is belonging to an organization even desirable? Is it possible to be a part of a group without killing your manliness? In this post, we take a look at William H. Whyte’s classic, The Organization Man and what it can teach us about balancing your manly individuality with membership in an organization.

The Organization Man Circa 1956

In 1956, The Organization Man was published and it quickly became a bestseller. William H. Whyte offered a searing evaluation of the values and ethos of 1950’s society. Marked by their relative apathy to politics, philosophy, and rebellion, the so-called “Silent Generation,” was coming of age and heading out into the workforce. The goal of many a middle-class man during this time was to land a job at a plumb corporation, give his full loyalty to the organization, move up the ladder, and enjoy a secure retirement.

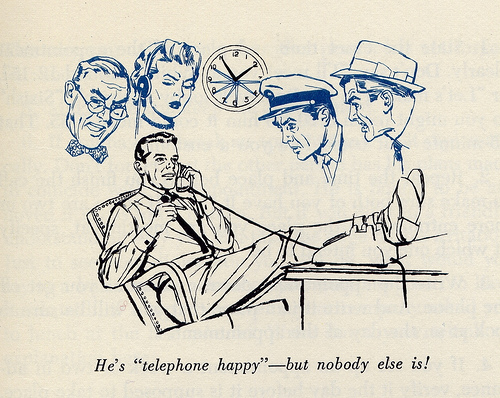

Whyte was alarmed at the enthusiastic willingness of these new hires to subvert their desires and their individuality to the corporation. He was most discouraged at the amount of pressure, in the form of new sociological mantras, that was leading them to do so.

Social scientists during this period proposed that man was most happy when he belonged, and that “belongingness” was one of the most important characteristics of a potential employee. This “Social Ethic” lauded the cooperative group over the individual. The virtue of the 1950’s was one’s ability to get along with others. The role of manager, the facilitator of cooperation, was greatly elevated and prized, while the role of leader was demoted. For if a group had a leader, then all members’ viewpoints were not equally valued. Whyte believed these ideas were fatal to individual identity and innovation. He argued that the elevation of “belongingness” over genius and leadership would impede both individual growth and satisfaction and the progress of society and business.

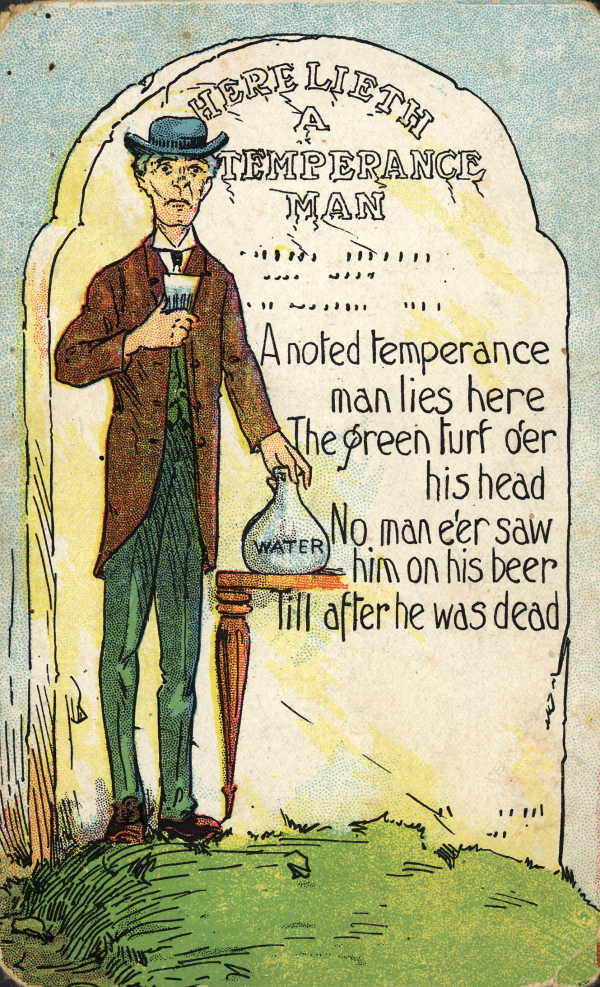

Of course the Silent Generation’s devotion to becoming an “organization man” did not last, followed as they were by the Baby Boomers, who grew up in the time of Watergate, Vietnam, and the turmoil of the civil rights movement. Disillusioned with the organizations they had been reared to respect, young people actively and openly questioned all the old pillars of society: government, religion, business, and education. The standard of belongingness was turned on its head; a person’s worth was now based on how individualistic and independent they were from the traditional standards of conformity. It was all about doing your own thing. The value of the individual reigned supreme over that of the organization.

Organization Man defined a generation; the idea of the “Organization Man,” like that of his contemporary, “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,” took on a life that transcended the book itself. It left us the inedible image of the soulless corporate drone, the man in the gray flannel suit, willing to subvert his individuality to pay a mortgage. But this picture and the haze of time have obscured what Whyte’s real message was. Whyte was not entirely opposed to organizations or even conformity per se. He argued for “individualism within organization life.” “The fault is not in organization,” he said, but “in our worship of it.” At the heart of his message was the warning that when it came to the balance between individuality and “belongingness,” the pendulum had swung far too much in the direction of the latter.

Several generations later, it now seems the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction. Of course times have changed. Men today understand that giving their loyalty to a corporation won’t be rewarded; they’ll probably be downsized during a merger and or when their job is outsourced. But men are loathe to join any kind of organization at all. They live increasingly private, isolated lives. They won’t join as much as a bowling league. The ideal is to be as unfettered and free as possible, without having commitments to anyone or anything. Yet they are missing out on the benefits that belonging to an organization offer a man.

Why belong to an organization?

Organizations get things done. You may feel satisfied with yourself sitting at home, reading blogs, and posting rants about the state of the world on Facebook, but you’re not really changing anything. While we love the idea of completely grassroots movements, the truth is that it’s organizations that get things done. If you look at the civil rights protests of the 1960’s, it may appear to be the ultimate grassroots movement, with one rugged individual, MLK, and thousands of other individuals getting together. But King and his followers largely worked through real organizations. Groups like the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference planned and orchestrated the events that tore down the walls of racial prejudice and segregation. Even our most potent symbol of rugged individualism-the American cowboy-is misplaced; many cowboys joined labor organizations to protect their rights as workers on the cattle drives.

Individual effort is not without merit; indeed, one man can change history. But an organization can multiple the impact of that effort many times over. In every time and in every place, it is has been organizations of men, from the loosely confederated to the firmly contracted, who have gotten the job done.

Organizations focus your energies. A lot of men today say that they’re not religious, but they are “spiritual.” But if you ask them what they doing to foster their spirituality, the answer is often “nothing.” The same thing goes for things like being “social aware,” or “into politics.” Yet the energies needed to change yourself and the world need to be channeled by some kind of vehicle. Think about electricity; without a wire to carry the energy, you can’t use it. If you have impulses to change society or yourself, joining an organization can help focus those energies. Some kind of structure will help turn your thoughts and desires into action. The electricity of your good intentions needs a conduit, an outlet to use the power. Joining a church or mosque will focus the energies of your faith; becoming a Big Brother will focus your charitable impulses; joining a political organization will give you something tangible to do with your idealism.

Organizations motivate you. How many times do you sit at home thinking about all the good intentions and goals you have for your life and then fail to act on them? Isolating yourself is a surefire way to drift through life. You never have any responsibilities, of course, but then you never grow either. Organizations provide some accountability to your goals and a source of motivation to get better. You may think you’re an awesome runner, jogging around your neighborhood every night. But why don’t you joining a running club and have some guy around to push you to go faster and needle you when you don’t show up? Similarly, joining a service organization requires that you show up to projects that you sign up for. If you have trouble motivating yourself to reach your goals, join an organization which will help your progress.

Organizations force you to rub shoulders people unlike yourself. In our increasingly isolated lives, our social circles have gotten smaller and smaller. We work with people like us with the same level of education and we hang out with friends from similar socio-economic backgrounds. We rarely rub shoulders with people from different spheres of life. This is fatal to democratic society. Groups of like minded people tend to move to more extreme versions of their initial position. Organizations provide you with the opportunity of getting to know a wider spectrum of people. Join a fraternal organization and befriend some old guys. Join a diverse church and get to know people from a different side of town.

Organizations need good men. Many men stay away from joining organizations because they are disillusioned with them. They stand on the outside and criticize perceived corruption or hypocrisy. Yet this turns into a self-fulfilling prophecy. When good men drop out of these organizations or refuse to join them, the criticism only becomes truer. If every virtuous man drops out of politics because he believes that it’s corrupt, politics will only become more debase. If organizations have any chance of changing, good men have to stay and work for change from within. Change will be slow, but when men stay on, join in, and work for change, it will happen.

Balancing Conformity and Individuality

There are only a few times in organization life when he can wrench his destiny into his own hands-and if he dos not fight then, he will make a surrender that will later mock him. But when is that time? Will he know the time when he sees it? By what standards is he to judge? He does feel an obligation to the group, he does sense moral constraints on his free will. If he goes against the group, is he being courageous-or just stubborn? Helpful-or selfish? Is he, as he so often wonders, right after all? It is in the resolution of a multitude of such dilemmas, I submit, that the real issue of individualism lies today. ~ William Whyte, The Organization Man

Of course, organizations should not be looked upon as an unmitigated good. A man should join an organization which benefits him, but still allows him to hold onto his individuality. A man must acknowledge that it is sometimes not an easy line to walk. Whyte believed that the 1950’s Social Ethic was dead wrong in its denial of the conflict between the individual and society. This tension will always exist. Whyte believed that every individual should face these conflicts and wisely negotiate them. Here are some guidelines for balancing the tension between allegiance to self and loyalty to an organization

Never blindly join an organization. The Hare Krishnas may be friendly and offer you free food, but don’t join up until you’ve done your homework. Don’t join things on an emotional whim. Take your time, and choose an organization that lines up with values and will help you become a better man.

Be indispensable. The more indispensable you are to an organization, especially a business or corporation, the more freedom you will have to be yourself and dissent when appropriate. If you are a cog in the wheel, and there are 100 more cogs who could do the same job, then you are under more pressure to do exactly what you boss says. If you’re hard to replace, or you know you could be hired somewhere else very easily, you’ll be freer to retain your individuality.

Prize your individuality. Whyte’s beef with the 1950’s Social Ethic was its belief that “belongingness was the ultimate need of the individual.” Don’t get so caught up with your group that you come to believe that it is always true that what is good for the group is good for the individual. Whyte advises to give “your energy to organizations, but not too much allegiance.”

Be aware of your conformity.

To be aware of one’s conformity is to be aware that there is some antithesis between oneself and the demands of the system (being aware of one’s conformity doesn’t make you a conformist). This does not itself stimulate independence, but it is a necessary condition of it. ~ The Organization Man

Strive for a healthy sense of self-awareness; regularly evaluate why you’re doing what you’re doing and how okay you are with it.

Don’t give up individuality now in hopes of regaining it later. Whyte spoke of men on the bottom of the corporate ladder who chafed at the amount of kowtowing they had to do. Yet they labored under the impression that if they put in the time and worked their way up to the corner office, they’d have more freedom to be themselves and use their own ideas. The truth then, as it is today, it that those higher up, while sometimes given a bit more leeway, are still under constraints to conform to their role. Think about it: if you have a job in which you constantly conform and act like someone else, then when you finally get promoted, you’ll be put in a position suited for your alter ego, not the real you.

If an organization fundamentally violates your values, if it forces you to make choices that compromise your conscience, then it is time to leave. True loyalty is a manly virtue in short supply. Don’t bail from an organization because of a rough patch, or new policies with which you disagree, or your offense at a fellow member or some behind the scenes politicking. These kinds of things happen in every organization. Stay on and be a force for change. On the other hand, don’t turn a blind eye to grievous misdoings. If an organization fundamentally violates your values or conscience, then it is times to make an exit.

Remember that the group is not the ultimate source of creativity. Whyte felt that the belief that groups were the best source of innovation was a crock. Groups are inherently non-creative, he argued, because members must strive to compromise, agree, and come to a consensus. The ideas which result tend to reflect the lowest common denominator between the group’s members. Don’t rely on an organization for your ideas. Formulate your own thoughts and then bring them to the group for debate and refinement.

Remember that outward conformity can sometimes be a secret weapon. The greatest catalyst for change may be the man who outwardly conforms while “secretly” working for change. Whyte wrote:

And how important really, are these uniformities to the central issue of individualism? We must not let the outward forms deceive us. If individualism involves following one’s destiny as one’s own conscience directs, it must for most of us be a realizable destiny, and a sensible awareness of the rules of the game can be a condition of individualism as well as a constant constraint upon it. The man who drives a Buick Special and lives in a ranch-type house just like hundreds of other ranch-style houses can assert himself as effectively and courageously against his particularly society as the bohemian against his particular society. He usually does not, it is true, but if he does, the surface uniformities can serve quite well as protective coloration. The organization people who are best able to control their environment rather than be controlled by it, as well aware that they are not too easily distinguishable from the others in his outward obeisances paid to the good opinions of others. And that is one of the reasons they do control. They disarm society.

When an organization does not meet our expectations and we become disillusioned with it, the temptation is simply to leave it behind. But we probably joined that organization in the first place because we believed in its foundational principles. Those principles may now be obscured by policies or leaders with which we do not agree. But by leaving, you leave behind any possibility of redeeming that organization. If all the men with the vision of what that organization could become depart, then it will never reach its potential. Sometimes it’s better to stay and outwardly conform, while actively working for change. Others in the organization will trust you, as you seem to be with the program, and yet really you will be subverting the status quo behind the scenes.

For example, I had a friend who worked for a small non-profit organization that monitored human rights abuses in foreign sweatshops. He did valuable work there, but his work had a small impact. He was offered a job to work for Nike, helping to improve their sweatshops. While my friend was loathe to join a corporation with a such a record of worker abuses, in many ways by “conforming” to be a Nike employee, he would actually gain more influence in changing the industry as whole.

How do you know if you’ve conformed too much to the organization? How do you know if you’ve cooperated too much or surrendered too much of yourself? Whyte defined the following as the “terms of the struggle:”

To control’s one destiny and not be controlled by it; to know which way the path with fork and to make the running oneself; to have some index of achievement that one can dispute-concrete and tangible for all to see, not dependent on the attitudes of others. It is an independence he will never have in full measure, but he must forever seek it.

What do you think? How do balance being part of a group and maintaining your individuality? Drop a line in the comment box and let us know.