What is the ideal man?

This is a question that philosophers have pondered over and riffed on for millennia.

Many philosophers have sketched out a vision of an ideal man who, unsurprisingly, encompasses the values that represent the pinnacle of their philosophical beliefs. These conceptions of ideal men are similar in that they all require reaching beyond human defaults to develop greater excellence, but each differs as to which virtues should be more or less emphasized to achieve that excellence. While none of the ideals can ever be perfectly embodied, they serve as aspirational models, guiding individuals to strive for personal growth and virtuous flourishing.

Below, we explore seven of these conceptions of the ideal man from seven different philosophers.

Note: Understanding these archetypal ideals requires a deep understanding of the philosophies that inspired them. Libraries of books have been written about the philosophies we describe below. For brevity’s sake, we don’t get into the nuances of these ideal men. But we’ve provided links to additional resources so you can further explore the ideas behind them. Hopefully, these short sketches will inspire you to learn more!

Plato’s Ideal Man: The Philosopher-King

Plato, the renowned ancient Greek philosopher, proposed an ideal man known as the “philosopher-king.” In his seminal work, the Republic, Plato aimed to define justice and outline the structure of a model society. In his vision, society would be composed of three groups that corresponded to what he believed were the three parts of the soul: the producers, workers who represented base desire; the auxiliaries, soldiers who represented thumos, or spiritedness; and the guardians, warrior-leaders who represented reason.

Philosophers-kings would be chosen from the guardian class after a long and rigorous education and testing process, which Plato likened to refining gold. During their formative years, the guardians would cultivate the physical and mental faculties necessary for their future roles, beginning with a focus on gymnastics and music. As they matured, they would delve into the study of war, politics, Socratic dialogue, and the Forms — the abstract and eternal concepts that underpin reality. Once they reached the age of thirty-five, a test would determine the most qualified candidates for leadership positions within the city. Service in these leadership roles acted as another test to identify potential philosopher-kings. The guardians who excelled in these roles would be selected to be philosopher-kings at around age fifty.

The philosopher-king’s extensive education would equip him not only with the skills of governance, but also with a deep understanding of eternal ideals, particularly the Form of the Good. This knowledge would enable him to lead with wisdom and justice and make decisions that benefited society as a whole.

Further Resources:

- What Is a Man? Plato’s Allegory of the Chariot

- A Primer on Plato: His Life, Works, and Philosophy

- Podcast #496: What Plato’s Republic Has to Say About Being a Man

Aristotle’s Ideal Man: The Great-Souled Man

Aristotle, Plato’s famed student, presents a different ideal man in his Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle’s concept of the ideal man is the “great-souled man” or the “magnanimous man.” For him, the pinnacle of manliness was the achievement of eudaimonia, a state of flourishing. For Aristotle, eudaimonia required not just excellence in virtue, but excellence in everything else: health, wealth, beauty, friendship, speaking, and more. Aristotle’s great-souled man embodies excellence in both inward traits and outward qualities.

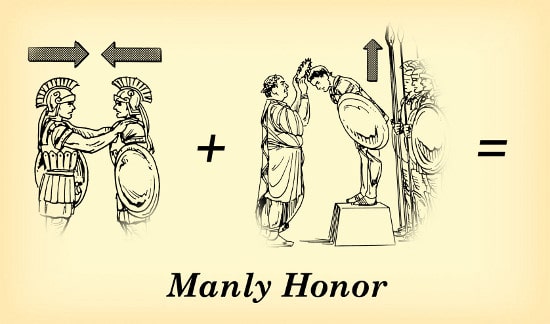

The great-souled man has a measured sense of pride. He takes pride in his virtues and achievements, focusing only on significant accomplishments rather than trivial matters.

Moreover, the great-souled man maintains a sense of honor; he not only cultivates excellence for excellence’s sake, but he expects and values the recognition of his excellence by others. Not just any others, however; the great-souled man seeks the respect of those he considers his equals. He doesn’t care about garnering the approval of the masses.

Aristotle’s ideal man also exhibits the type of courage Ernest Hemingway called “grace under pressure” and remains calm and dignified in the face of setbacks.

In his interactions with others, the great-souled man displays magnanimity. He ignores slights and doesn’t hold grudges. He refrains from gossiping and talking ill of others. While the great-souled man avoids thinking and speaking poorly of others, he’s also reluctant to offer praise, as that would be seen as subservient. What’s more, he’s quick to grant favors, but avoids asking for them, as that too would signal his inferiority.

In short, the ideal Aristotelian man is a virtuous aristocrat.

Further Resources:

- Aristotle’s 11 Excellences for Living a Flourishing Life

- Podcast #515: Aristotle’s Wisdom on Living the Good Life

Confucius’ Ideal Man: The Gentleman

Confucius, an ancient Chinese philosopher, emphasized the cultivation and performance of proper social conduct and virtues. In Confucianism, the ideal man is known as a junzi, often translated as a “gentleman” or an “exemplary person.”

A junzi demonstrates noble behavior and comports himself appropriately in all situations. The Confucian gentleman shows respect and deference to his elders and teachers while treating those beneath him with humanity. He observes society’s rituals and forms with sanctity and circumspection. He embodies ren, or consummate conduct, which is a power that inspires others to be good and noble through one’s example. The junzi’s actions uplift and ennoble others, encouraging them to do their own part to maintain social harmony.

The Confucian gentleman continually seeks self-improvement. He engages in book study and seeks to apply his knowledge in practical situations. Confucius believed that with dedication and the cultivation of consummate conduct, any individual could become a junzi, contributing to the betterment of society through his exemplary behavior.

Unlike the Aristotelian great-souled man, the Confucian gentleman adopts a humble orientation. He avoids excessive pride, recognizing its potential to disrupt social order.

Further Resource:

Nietzsche’s Ideal Man: The Übermensch

Friedrich Nietzsche, a German existential philosopher of the 19th century, introduced his famous ideal man — the Übermensch or Superman — in his work Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

For Nietzsche, becoming an Übermensch is a spiritual goal or way of approaching life. The way of the Übermensch is filled with energy, strength, risk-taking, and struggle. He represents the drive to strive and live for something beyond oneself while remaining grounded in earthly life (there’s no room for other-worldly longings in Nietzsche’s ideals).

In a modern world where God is dead and meaning gone, the Übermensch creates his own meaning. Instead of feeling dread that life has no inherent purpose, the Übermensch finds the process of meaning-creation joyful. He embraces the challenge of fashioning his own purpose with laughter.

The Übermensch is really the full manifestation of Nietzsche’s will to power: the drive to assert oneself in the world — to be effective, leave a mark, become something better than you are right now, and express yourself.

Nietzsche never states exactly what the ideal man should strive for beyond himself or what he should create. Being filled with the creative force was the important thing. Each individual must determine his own path into the transcendent.

Further Resources:

- A Primer on Friedrich Nietzsche: His Life and Philosophical Style

- Say Yes to Life: An Accessible Primer on Nietzsche’s Big Ideas

- Podcast #480: Hiking With Nietzsche

Didymus’ Ideal Man: The Stoic Sage

The ideal man for the Stoic philosophers was something called the “Stoic sage.” While all the Stoics touched on and described the sage, Arius Didymus, a Stoic philosopher and the teacher of Caesar Augustus, did the most to flesh out this ideal. His descriptions of the sage were quoted at length in a 5th-century book by Joannes Stobaeus that compiled extracts of the works of Greek and Roman philosophers.

The Stoic sage represents the perfect embodiment of Stoic principles, characterized by the alignment of his life with nature. The sage’s life is tranquil, guided by virtue, and free from disturbances caused by external circumstances. He recognizes that external factors, such as wealth or reputation, are beyond his control and therefore not essential for happiness. Instead, the sage’s happiness, his eudaimonia, stems solely from the cultivation of virtue and the correct understanding of mental impressions.

Further Resources:

- Podcast #316: An Introduction to Stoicism

- Podcast #537: How to Think Like a Roman Emperor

- 5 Ancient Stoic Tactics for Modern Life

Camus’ Ideal Man: The Absurd Man

Albert Camus was a French existential philosopher, novelist, and playwright. His most important contribution to existential philosophy was his idea of “the absurd.” For Camus, the absurdity of life is created by the juxtaposition of two ideas: 1) the universe is inherently meaningless and indifferent to human concerns, and 2) humans have an innate drive to find meaning in life.

Camus’ ideal individual, the “absurd man,” confronts the absurdity of existence with defiance and lives authentically in the face of meaninglessness. He is able to acknowledge the existential emptiness of the world without succumbing to despair or nihilism. He embraces the void directly with passion and joy. He rejects the illusion of imposed order, and in fact finds meaning in this very act of rebellion. He creates his own purpose and lives in the moment.

Camus laid out his ideal of the absurd man in his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus.” In the Greek myth, Sisyphus is condemned by the gods to push a boulder up a hill for eternity, only to watch it roll back down each time he reaches the top. For Camus, Sisyphus embodies the human condition: our endless search for meaning is as futile as Sisyphus’ eternal task. But Camus imagines Sisyphus as bearing a smile as he descends to retrieve the boulder, suggesting that there’s a kind of triumph, dignity, or even happiness in fully acknowledging the absurdity of life and choosing to push on regardless.

Kierkegaard’s Ideal Man: The Knight of Faith

Søren Kierkegaard, the 19th-century Danish father of existentialism, described his ideal man as the “Knight of Faith.” In his work Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard explores the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac to illustrate this archetype.

Kierkegaard contrasts the Knight of Faith with another type of individual: the Knight of Infinite Resignation. The Knight of Infinite Resignation renounces worldly attachments and makes great sacrifices for a higher cause or ideal. He resigns himself to these losses and finds peace by letting go of finite and earthly desires.

The Knight of Faith, however, goes beyond resignation and maintains an unwavering belief that he can still receive what he sacrificed due to his absolute faith in God. Abraham was a Knight of Faith because he simultaneously gave up Isaac for sacrifice while still believing that God would allow him to keep his son.

The Knight of Faith embraces the happiness to be found in the finite while also believing in the reality of the infinite — and the power of the infinite to make seemingly impossible things possible. To become a Knight of Faith, one must demonstrate faith through action, as Abraham did when he raised his dagger to sacrifice his son. The Knight of Faith takes bold leaps into the unknown.

Further Resources: