When Daniel Zia Joseph decided to join the Army at the unusually late age of 32, he solicited advice from his buddies who had served in the military on how to succeed in the experience and become a good officer and leader. Today, he passes on these leadership lessons to us.

Dan is the author of Backpack to Rucksack: Insight Into Leadership and Resilience From Military Experts, and he first shares why he decided to join the Army at an older age and what he would tell other guys who keep thinking about doing the same thing. We talk about how he prepared himself to be a leader and how getting his masters in organizational psychology helped deepen his development. We then discuss the lessons his military mentors imparted to him, including why you should pursue attrition, the importance of command climate, using psychological jiu-jitsu, and the difference between garrison and field leadership.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- Dan’s video about joining the military after age 30

- AoM Podcast #875: Authority Is More Important Than Social Skills

- AoM Article: Are You a Strategist or an Operator?

- Once an Eagle by Anton Myrer

Connect With Dan Joseph

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. When Daniel Zia Joseph decided to join the army at the unusually late age of 32, he solicited advice from his buddies who had served in the military on how to succeed in the experience and become a good officer and leader. Today, he passes on these leadership lessons to us. Dan is author of Backpack to Rucksack, insight into leadership and resilience from military experts. And he first shares why he decided to join the army at an older age and what he would tell other guys who keep thinking about doing the same thing. We talk about how he prepared himself to be a leader and how getting his masters in organizational psychology helped deepen his development. We then discuss the lessons his military mentors imparted to him, including why he should pursue attrition, the importance of command climate, using psychological Jiu-jitsu and the difference between garrison and field leadership. After the show is over check out our show notes at aom.is/militarymentors.

All right, Dan Joseph, welcome to the show.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Hey, glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: So you got a new book out called Backpack to Rucksack, where you share insights on leadership and resilience that you learned in the military and in your work in organizational psychology. But before we talk about the book, let’s talk about your experience joining the Army because you did so at the age of 32, which is unusually late in life. A lot of guys aren’t joining the Army at age 32. So what’s the age limit for joining the Army? Were you pretty close to the the upper end?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yes. So as a commissioned officer, I needed to commission by the age of 33. And I signed up at 32. So the recruiter definitely had my back against the wall saying you either sign the contract or you’re going to miss your window. So I jumped in. But yep, definitely pushed against that that age limit for the Army. Each branch has a different age limit. But I tell people to… I receive a lot of questions from people asking if they’re too old. And I tell them always ask a recruiter because those numbers do change depending on the needs of the government and military, what branches need.

Brett McKay: So let’s talk about your life before you joined and like then what led you to signing up at age 32. So what was going on before age 32? So you’re 18. That’s when most guys, when they’re thinking about joining the army, they join right at a high school or maybe in college. What were you doing? And then talk about what was going on right before you joined at age 32.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yeah. So I have a pretty, pretty unique story, I guess, to myself. I worked in biotech for quite a while here in San Diego and a lot of genetic research companies out here. I’ve worked with companies that were genetically modifying specific organisms to create industry, new industry products, some wild stuff. And it led into a job involving machine learning algorithms and borderline AI back then a few years back, to basically enhance genetic codes to optimize genes and snip out disease markers from humans, from animals, a lot of really cool stuff happening. But I was essentially working initially in the laboratory and then I moved towards business development. And what really pushed me to join the military was when ISIS was actually attacking civilians and the populace in Iraq. My family is from there. My parents escaped barely with their lives back in the ’70s. And I had a lot of friends that I made here in San Diego who were on the SEAL teams, different branches who were deploying to go fight those guys.

And as I was over here, working in a world where we were literally using computer software to design genetic code and enhance the human species in a way that’s just absolutely mind blowing, My friends were in this primal fight in a war zone that they had nothing to do with. They were entering into that fight selflessly to go save people. And they came back with these stories that were just… They were literally fighting in the villages my parents grew up in. And I felt this deep desire to put on a uniform and contribute in any way possible. I just felt it was my duty because America saved my family. They gave us a place of refuge and that just really weighed heavy on me. So as I’m working on my company, I eventually started my own company and was making pretty good money, but then my friends would come back from these deployments telling me about some of the stuff they got into. And I just felt so compelled to let go of what I had here and to join the military, just to be able to tell myself before I’m on my death bed someday, like, hey, I did it.

Brett McKay: And you also talk about in the book during that time when you were working, you’re working hard, making good money. There’s also a hint of you felt kind of restless. There was drinking and you hang around the wrong kind of crowd and you just felt like you weren’t going anywhere either.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yeah. So, especially if you’re the child of say immigrants and you grew up in the United States. So, I was born in the US my parents, like I said, they left Iraq in the ’70s. I was really trying to discover myself in a way here that… Yeah, it involved the wrong crowd, for sure. I got involved into what I thought was sort of popular behaviors, a lot of drinking, and then that quickly moved into a crowd that use drugs, partied pretty hard, play hard, work hard. And I got caught up in a lifestyle where it was just… It was driven sort of by how cool people thought you were based on this persona. And it felt… It was extremely superficial, very high quantity, low quality with the relationships. I made some good friends, but it definitely didn’t require discipline. It just required showing up, getting drunk and trying to have as much fun as possible. But when I started meeting friends in the military, I noticed a stark contrast between their behaviors, their level of discipline, their presence, their physicality, how they approached life. And I was drawn to their mindset. They were super sharp, super driven. And they definitely had goals far beyond what I was doing, which was just basically going from hangover to hangover. And these guys were getting after it, training all the time. And it was really inspiring to me.

Brett McKay: Okay, so you joined up at age 32. Did you face any challenges joining at that age?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Honestly, no, I didn’t. I have a lot of friends who were in the military at the time. And they their number one piece of advice to me was stay physically fit. Because regardless of age, when you show up, your body is… It’s your resume to the guys around you, especially as an officer. People want to be led by somebody who inspires them. And when you show up in good shape physically, and you can do the rucks, you can do the runs, pull ups, push ups, everything that they test you in, the guys are going to follow you, they’re going to want to be a part of your group. And age was never an issue for me. The biggest thing I was told was to never use my age as a way to talk down to anybody or be condescending. Basically, if people wanted to tap into whatever life wisdom I had, then I would allow them to ask for that. But I was definitely schooled on, Hey, just show up, keep your mouth shut, be present, and just stay physically driven. That’s going to motivate people.

Brett McKay: So what did you end up doing in the army?

Daniel Zia Joseph: I was a combat engineer. So I was a platoon leader for 19 months. It was a separate platoon is what we call it. And essentially, we would simulate combat exercises with minefields and wire obstacles, tank ditches, basically, simulating what World War III may look like.

Brett McKay: So like, what advice would you give to older guys who… They keep thinking about, should I join the military? What should I do? Am I too old? What advice you have for them? Would you just recommend to just go for it?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yeah, I mean, I definitely tell people, if you’re thinking about it, at least start training for it. Because here’s the thing, even if you don’t make it into the military, the fact that you got up and trained yourself and started running and started doing the dieting and all of that, that’s required to just be at your top shape, it will progress you to becoming a better version of yourself. So I don’t see any downfall to pursuing that there’s a lot of people that reach out to me saying, Hey, I don’t know if I’m going to get cleared for some some medical things, or maybe some past criminal activity or whatever it is that happened in their life. And I say, don’t close the door on it, there might be a recruiter out there who’s going to find a waiver for whatever it is you’re dealing with. And don’t ever let age or any sort of negative self thought hold you back. Don’t limit yourself. And it’s amazing to see what people have. I mean, I’ve talked to guys who’ve lost over a 100 pounds just training for a military gig. That’s phenomenal.

Brett McKay: All right. So there’s the big thing. If you’re older, just stay in shape. Like if you’re fit, they’re going to take you. If you, even if you’re at that age limit.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Absolutely. Yeah. Fitness is like the number one thing because you just, you have to be able to pass those fitness tests. Yeah.

Brett McKay: I think what I heard is that it’s something like 70% of young people wouldn’t be able to qualify for military service.

Daniel Zia Joseph: I’ve heard that.

Brett McKay: A lot of that is because of obesity. That’s why they’re having recruiting problems. So how did joining the army change your life and what are you doing now?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Well, so I’m out now. I was in for three and a half years. I’m actually thinking about signing another contract. I have a MEPs appointment coming up to go in and get medically screened again. But being in the military really changed my life in ways that I never thought. I definitely was close to the troops. I loved being around them. It taught me a lot about leadership. It taught me a lot about how to relate to others in an organization that’s just constantly under high stress, high op tempo, just back to back training. It really left a mark on me that I didn’t expect. So I don’t know what to say. I could talk a lot about that.

Brett McKay: And also while you were in the military, you got your… That’s where the work in organizational psychology came in, correct?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yeah. So the lockdowns impacted a lot of our training and during the downtime I thought to myself, what can I do to optimize? I didn’t want to just survive the lockdowns. I really wanted to thrive during the lockdown. So I thought, well, work out three times a day, don’t drink a drop of alcohol and get a master’s degree. And I lived by that. That was my day in and day out. And I wanted to come out of the lockdowns better than I ever was. And getting the masters was eye opening to me, because as I’m leading these soldiers, as I’m seeing the impact of mental health, as I’m talking to dudes that have been to war, the first and second waves in Fallujah and Iraq and dealing with all these issues. And, I’m working with them, I’m seeing the physiological response of what happens to them at work, based on what they experienced. Simultaneously, I’m writing these articles and doing my research for my master’s, it was just an amazing connection that I was realizing between the human brain, interpersonal relationships, organizational dynamics, and it definitely added a lot of depth to my understanding of what was going on.

Brett McKay: When you got out with your initial contract, did you go back to the corporate world or what was going on then?

Daniel Zia Joseph: So that was actually pretty recent, like a few months ago. So I’m currently working on another master’s degree and I can tell you that… I’m 36 now, And I can tell you that all the training I did in the military left… It put a fire in me. I’m in the best shape of my life right now, and I cannot sit still. I mean, I’m working out multiple workouts a day, still doing ruck runs, still staying physically active. And I thought that when I got out of the military, I would be totally okay with a much more sedentary life, back into an office environment. And that’s… Yeah, that’s definitely not what happened. It’s really shocking to me. So I’m currently doing some training with a group of guys that are working on some amazing pipelines in the military. They have some tough pipelines ahead of them, and I’m working side by side with them right now at the gym, doing some runs with them. And they’re motivating me a lot more than I thought I could ever be motivated. So that’s why I’m kind of looking into some additional contracts in the next few months, actually.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about your book. So Backpack to Rucksack, what you did is leading up to you trying to figure out whether you’re gonna sign up with the Army. And also during that time when you were going through the process of training and whatnot, you got a lot of military friends and that you were talking to them, asking them for advice. Like, what do I need to know when I’m going through this process and becoming a commissioned officer? How do I handle this situation? And what you did in the book is you shared these insights you got from these various friends of yours in the military from all branches of the military. And then you combine that with your research that you’ve done in organizational psychology. And so each chapter highlights a different concept or topic. And in the first part of the book, the first chapter, you talk about this bit of advice you got from… I think it was a Green Beret friend of yours, about pursuing attrition in life, but also in the military world. What did he mean by that?

Daniel Zia Joseph: So his advice was to pursue pipelines in the military that people complained about. Pursue… Basically his philosophy is that any route you want to take in life that other people are afraid of or that they’re being just really critical or negative about it’s a filtration mechanism. It’ll stop the wrong people from pursuing it and it’ll filter for the stronger candidates. And he was just saying, make sure that… When you join the military, if you do want to find group of brothers around yourself that are just operating at a level that is far beyond your own perceived limitations, you need to go down some hard pads that remove the guys who just tap out early. And he said, next thing you know, you’ll be rubbing elbows with other people that are like-minded who sort of keep their mouth shut and just work really hard.

Brett McKay: And this is applicable outside the military too, in work, in your physical fitness. If you want to rub elbows with the best, just top-notch individuals, do the hard stuff ’cause that’s gonna filter out all the riff-raff.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Essentially, that was exactly how he approached life, yep.

Brett McKay: So let’s talk about another concept you learned from a friend of yours who’s a marine named Will, and he taught you the importance of command climate. What is command climate?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Essentially, it’s culture. It’s work culture. In the military, it’s really unique because the person at the top in whatever unit you’re looking at tends to… They set the temperature for the entire unit. So if you have someone who is super physical and super into fitness, you’ll see that everyone below them, all the subordinates suddenly begin to really invest in fitness. They suddenly become really gym oriented. But on the converse side of that, let’s say you have someone who is really negative and really, it’s an overused word, but if they say they’re toxic or have certain insecurities or they have a shame-based orientation towards their leadership style, you’ll see people below them begin to treat others the same way. And you can’t really change command climate in the military. You can’t walk into a unit and go up to somebody at that rank and say, hey, sir, hey, ma’am, I need you to conduct yourself differently, so we can all experience a whole different climate. What you get is what you get. And Will’s advice was you gotta make the most of it. If it’s bad, it’s gonna be bad, but you gotta just figure out how to handle it until that leader leaves and you get someone new. And if it’s good, then definitely count your blessings and just… You’re gonna have a blast in the job for sure. They’re gonna make the job awesome.

Brett McKay: Did you have any experiences of really bad command climate in the corporate world or the military?

Daniel Zia Joseph: I mean, definitely I’ve seen good and bad. I mean, as we all have, I’m sure, so definitely have seen the impact of it. And what’s astounding to me is the way in which it compounds the stress around us, because, I tell people attack problem sets, don’t attack people. If something sucks, if something needs to be enhanced or optimized or modified, whatever it is, the military and the corporate world, look at the problem set before you. You don’t have to make it personal. You don’t have to bring emotions into it and attack others and involve ego. So what I’ve seen good leaders do is when there is an issue that needs to be addressed, they are enablers of people. They enable subordinates. They enable everyone around them to find solutions. And if you fail, then okay, so be it, but pick yourself up and find the next solution that’ll work. Own it and make it great. Figure out a way to make the situation better. But what I’ve noticed toxic leaders will do is they will have a more fixed mindset as Carol Dweck talks about growth versus fixed mindset. They’ll sort of approach the situation as, hey, nothing’s gonna change. This is the way it is. Shut up and fall in line. I don’t care what your opinion is. I don’t care what data you have from your perspective.

I don’t see a viable solution and I don’t care that you think there is one. Just carry on, keep everything status quo how it is. And it’s stifling. And it’s not just on the job. We take it home with us. It follows us home, that stress, that level of… That feeling of not having a voice. It’s really repressive. And it feeds a lot into the personality of the leader. So again, if it’s a great leader, if there’s somebody who’s open-minded, you’ll feel that. There will be a sense of levity, even amidst highly stressful conversations or situations.

And one thing I will say, there was an EOD that talked to us about his experience in Iraq. There was a guy that got blown up, and there was a body on the ground. And I mean, definitely the dude was jacked up. And the medic started panicking. And the EOD ran up to him because in those situations, the medic takes control, right? Takes over. A lot of the guys who survived the blast, were looking at the medic starting to lose control. So this EOD ran up to him and grabbed him and said, look, man, I need you to take a breath, and I need you to focus. Do what you can to save this guy. If you can’t, fine. But do what you can, but everyone’s watching you right now. And what he was telling us as new officers, he said, look, your attitude is everything in the military because calm is contagious, just the same way that panic is contagious. So whatever type of leader you’re going to be, the men around you, the women around you are going to pick up on that. So be sure to lead and conduct yourself in a way that you want other people to pick up. Because good or bad, they will pick up on whatever vibe you’re putting out into the unit.

Brett McKay: Okay, so yeah, in order to be a leader that creates a good command climate, it’s just… It’s a lot of self work, right? It’s working to learn how to control your emotions, working on your own discipline, working on those social and people skills, those soft skills, it’s a full-time job. It’s not just something that happens, it’s something you have to be intentional about.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Absolutely, and I learned that in the corporate world. When I started my own business, I had a mentor, George. He was like a father figure to me. And I was struggling with some high-power executives that were… I was in some negotiations that were just absolutely intimidating to me. And George pulled me aside in sort of a coaching seminar that we had together, a discussion we had. And he let me know. He said, look, basically, the man that you are privately, it’s going to come out in the room when you negotiate. And he said, the other men you’re dealing with are sharks. I mean, if they smell blood in the water, you’re dead. They’re going to tear you to pieces in a negotiation. So he said, you got to work on yourself. You got to know who you are outside of the business world, outside of the office, who you are privately, when you put your head on the pillow at night, when you look in the mirror, who are you? Once you figure out who you are, and you have a grasp on that, and you ground yourself in that, you can then approach the negotiations with that level of confidence that is gonna allow you to have better leverage, and other people will not take advantage of you. Situations that suck won’t take advantage of you.

They won’t change you. You will bring light into that dark situation. And that was one of the most profound pieces of information I received because I realized that, if I don’t work on myself, the guys around me are gonna suffer. My ego issues, my insecurities, my personal private hangups are gonna come out at work in the way that I speak to others and the way that I treat others. And then all of a sudden they have to manage my emotions for me. And the job’s stressful enough, especially in the military. Training can be life and death. And if I’m bringing my own ego issues and the guys around me have to manage that, man, I’m doing them a disservice. So yeah, absolutely. I encourage every leader, pick up books, read, study yourself because you’re gonna benefit the organization, you’re gonna benefit your relationships, your marriages, your relationship with your kids. Everything will benefit when you grow yourself privately and personally.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. So in the military, you have to deal with all sorts of personalities, especially big personalities. Did you have any experience dealing with difficult people with big egos when you were in the military?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yeah, I mean, the… It’s common to see people… And again, this happens in any organization, but when you see someone use their rank as a way of trying to stifle others, trying to sort of demand control… And psychology, they call that positional authority. You can have moral authority, you can have positional authority. Moral basically means when you walk in a room, regardless of rank, people, they trust you, they know that you know things, they see that confidence in you. Positional authority means, hey, do you know who I am? Do you know where I am on the hierarchy. Okay, cool. So fall in line, they rely on their rank. And yeah, I mean, I’ve seen that and I’ve had to manage that, absolutely.

Brett McKay: Did you have any military friends who gave you any advice on what to do with those big egos? People who were trying to use their positional authority to get things the way they wanted?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yeah, absolutely. So one of the biggest pieces of advice on that was my buddy Brad, he’s an EOD commander now, but he was deployed in Afghanistan. And he told me about some situations where guys would try to pull rank, and he would let them know… I mean, and this would happen in the battlefield, as he’s dealing with an IED. And he had to tell people, some people who’re very high rank to shut up and sit down, because if they continue to distract him, there could be fallout that’ll kill everybody around them. So what he taught me was, when you know something is correct, there’s a way to present it to somebody who’s an authority with a respectful attitude, yet assertive. Assertion is really important when you know something is right. So it is important to stand by what you know. However, depending on what personality you’re dealing with, you got to manage it in a way that they will be receptive to it. And at that point, it’s really dependent on the person that you’re dealing with because sometimes direct is the best approach. Other times you got to stroke their ego a bit. You got to find a way to… I don’t want to say play the politics of it, ’cause that can get really dirty, but you got to find a way to get them to have an open mind.

And this is where… I mean, I could talk for days about this, but this is something we learn in Jiu-jitsu as well. We call it working the angles, basically. Jiu-jitsu is all about having the right angle. Approaching leadership dynamics, it’s the same way. Certain leaders, again, hit them head on. They’ll respect that, they’ll respond to it. Other leaders, you can’t do that, because once you do it, it’s fight mode, and the discussion’s completely derailed.

Brett McKay: Yeah, you gave some examples in the book of… I think when you were in basic training, you had some guys who were kind of big dogging, right? They just kind of… They kind of walked around like they were the stuff, right? They had the stuff and they were just annoying. And they would do these things where they kind of confront you and try to assert themselves over you in the dominance hierarchy. And you talked about how you’re really tempted to just… I’m gonna punch back or I’m gonna push back, I’m gonna get angry about it. But like you said, you did some like psychological Jiu-jitsu on these guys to, instead of them being enemies or a liability, they actually ended up being an asset. Like what did you do to turn those guys from… Like you weren’t best friends with them, but they became guys who you could collaborate with and get things done.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yeah, I think in retrospect, maybe they were trying to size me up to see if I would stand up for myself. And in any case, I was very direct when I approached them. I maintained eye contact. I was very direct, but I also did it privately. I didn’t do it in a way… So they would… There’s a situation where I was being called out in front of the entire platoon. And this was in training, not my actual platoon, but back in the schoolhouse. And so what I decided to do is control my heart rate, control my breathing. It’s the same way like on the mats when I’m getting smashed by one of the black belts that I train with. I need to gain physiological control of my body, calm myself down. And then what I did is I directly approached one of these individuals and I let them know, hey, we’re going to have a conversation about this, but again, it’s not going to be emotional.

This is just gonna be man to man, we’re just gonna have a quick talk about this. And he quickly realized that I wasn’t there to start a fight, I was there to learn. I let him know that, I said, look, I know I’m new, I know you’ve been in the military for a while, I’m not here to be disrespectful. I’m not here to flex on anyone. I’m here to learn. So if you have something to teach me, I’m all ears. But I’m not gonna play this game of one-upmanship, that’s just not how I roll. And I learned that because of my high school friend, Tim, who introduced me to Jiu-jitsu. He told me that if you’re ever dealing with somebody who just absolutely wants to tear you to pieces on the mat and wants to smash your face into the mat, you need to tell them, I’m not here to fight. I’m here to learn. So if you’re here to fight, that’s not why I’m here. And it really has tremendously had an impact on the mats. So I started taking that principle into the military and it had the same impact. It was amazing.

Brett McKay: All right. So yeah, be direct, do it in private. You can be assertive, but not a jerk about it. I guess is the key. Let’s talk about the politics of military life. So you mentioned that that military can be political and by political, we mean that you do… The people who do and say things, whatever it takes to advance their career. Well, you talked about, you learned this from your military buddies that politics can get in the way of effectiveness. How so?

Daniel Zia Joseph: So, and again, this is highly applicable to the corporate world, to any organization. Some people will use their rank and authority to get their agenda done. Whatever their agenda is, usually I’d say to promote their own sort of resume, but they’ll do so at the expense of the well-being of those around them, not wanting to hear about inconvenient pieces of information about the organization, but that can quickly get dark. So what’s really important and the advice I received is listen to the people around you, give everybody a voice so you know what exactly needs to be improved to help others and any rank that… As you rank up, the higher rank you get, the more people you serve. It’s not the other way around, because a lot of people commonly think that with more rank and more authority, you have more power over more people. But if you look at it inversely, it really helps add a healthier context to the relationship. The more rank you have, the higher up you are, the more people you are actually serving as a leader.

And the way you serve those people is… And I get it, you can’t have a perfect solution that everybody’s happy with. But the more conversations you have, the more incremental improvements you can have throughout the organization by removing red tape wherever you can remove red tape, allowing people to get the schools that they want to get, to work towards the credentials, to pursue the education they need, to have time with their family, with their kids, if they need medical help, whatever it is, just allowing rank to be used to improve the unit and not to just demand sort of respect authoritatively.

Brett McKay: So take a servant leadership approach instead of thinking about, well, how can I advance the hierarchy and improve my own status and rank?

Daniel Zia Joseph: Right.

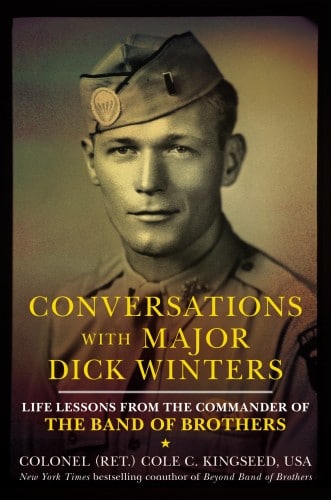

Brett McKay: Yeah. And for a book, I don’t know if you’ve read this book. It’s a great book that highlights the difference between a military leader who is very political and one who has that servant leadership approach. It’s a Once an Eagle. Have you read this book?

Daniel Zia Joseph: So that book is definitely the Bible to a lot of my friends. Yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah. No, so this book is written in 1968. It follows these two officers from World War I through Vietnam. One guy is Sam Damon, career army officer, started off as a private, and then he rose up to general officer rank and he was honorable. Like he was all about his soldiers. He was like the epitome, like he was the guy. And then the other guy who was the more political officer was this guy named Courtney Massingale. No honor, had no concern for his troops. All he cared about was going up in the rank. And it’s a great book if you want. It’s a beast of a book, but a lot of great lessons on leadership, especially about that dichotomy between being a political leader and a servant leadership type leader.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Definitely. We’ve had a lot of talks about that book. Yep.

Brett McKay: So a lot of the advice in the book is about just how to stay calm, right? Even when things are going just crazy around you. What was some of the best advice you got from your military buddies on staying calm during chaos?

Daniel Zia Joseph: I mean, essentially, just have an awareness of your physiological response to kind of zero out your own emotional impact in a situation. Because oftentimes, when, let’s say, a mission set suddenly changes, so we have a movement. We’re trying to get the convoy from one location to another. And everybody’s been briefed on it. And then suddenly a wrench gets thrown in. Because we were simulating combat as realistically as possible. And there’s tempers flare. People get real mad real quick when it’s 125 degrees and you’re in your full kit. And we’re talking about some dangerous terrain, some night movements. Things can get real sketchy real fast. And as a leader especially, if I were to feed into that angst with that same level of anger and frustration as I’m trying to brief the change in the mission, I mean, it would be horrible. It would just turn into this cluster of egos and sparks would fly. People would just be yelling at each other and I never wanted to do that. So the advice I received was, hey, look, when things suck, you just gotta calm yourself down, find your center. Again, remove the emotionality out of it, the primal limbic response of the brain. Get back into your prefrontal cortex. And I’m talking psychology here, but essentially get into your higher mind and come in there with a sense of awareness and transparency.

Like, hey guys, this is gonna suck. I know it’s gonna suck, all right, but here’s the change. We’re gonna do it, but let’s just… Let’s get it done. We know what needs to be done. And having that open and honest, that truthful approach, it helps kind of quell the anxiety of those around you. Because then they realize, you’re not leaving things undiscussed. Everything can be talked about. And then, yeah, we just kind of get over it. Like, all right, cool. Yeah, you acknowledge it sucks. I acknowledge it sucks as well. All right, let’s do it. And let’s do it safely. And let’s do it in a manner that’s efficient. But when people come in and say, hey, something changed. You’re going to do it. Don’t talk back. Get into the vehicle. Do this. Do that. Whatever it is that needs to be changed. Oh, man, there’s going to be some resentment that builds quickly.

Brett McKay: So you have a chapter on knowing the difference between garrison and field leadership. What’s the difference between the two?

Daniel Zia Joseph: So yeah, my artillery officer buddy told me that, Jazz. So, okay, so in the field, you deal with… Like let’s say desert terrain or whatever. It could be in the woods, it could be… I don’t know, wherever you are. But you’re dealing with more kinetic factors of the job. You’re dealing with weapons systems, you’re dealing with, adverse weather conditions, rough terrain, and if you’re a leader who… So in garrison, it’s on base. That’s more of the office side. That’s more the paperwork and stuff like that. So let’s say you’re great at the paperwork. If you go out in the field and you suck, then you could lead your convoy off a cliff. Conversely, if you’re really good at the tactics in the field and you’re good at moving people around and getting things done out there, but you come back to the office life and you don’t know how to work a computer or write a memo, then your guys are going to suffer because you’re not able to put in the awards for them. You’re not able to get them to the schools that they need to get to or help them with anything else that’s related to their personal lives.

So my buddy was telling me you could be two of three things in the military. Good at two of three things. You could be either a good officer in the field, you could could be a good officer in garrison or a good person. You can’t be all three, you’re always just two of those three. But he said always default to being a good person. ‘Cause whether you suck in the field or you suck in garrison, your guys are gonna have your back. But if you’re not a good person, then it doesn’t matter that you’re good at the other two, ’cause everyone’s gonna suffer. So that’s kind of the short and sweet.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think we wrote an article a while back ago about this difference between Garrison and Field, between Eisenhower and Patton. So Patton was probably… He was probably the better tactical officer. He loved being out in the field, being with the men and being in the muck and just being in the action. Eisenhower was more of a strategic officer, the Garrison. He was really good at people skills, negotiating, dealing with administrative things, things like that.

And because I think their personality suited those different things. And I think a lot of leaders, they get into trouble whenever they… They might be better as a field officer, but they get stuck in a garrison position or the opposite, like a garrison leader gets stuck in a field position. And I think the trick in leadership is finding out what you’re good at. And so this applies to the corporate world as well. You might be a guy who… Say you’re in sales or something. You’re really great being out in the field and talking to customers and dealing with other salesmen and encouraging them and motivating them. And maybe you get the promotion to manage a whole region, or maybe you’re at the office headquarters and you’re just miserable because it just doesn’t suit your personality. So I think that’s another trick of leadership is trying to figure out what you’re good at and leaning into that and not being tempted to go to something else because it might seem more prestigious or they might have more status.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Yeah, absolutely. And I would say the best way to handle that situation when things seem sort of out of sync with who you are is to rely on those around you. And again, being a leader is being an enabler. So enabling those people around you to compensate for those deficits, to use their strength to, as a team, build a better unit. So that’s huge. So if ego gets in the way and a leader says, no, I got this, I know the book on this, I know the solutions and I’ll fix it, I’ll figure it out. Everyone’s gonna stand around and just watch that leader fail. So it’s really important to just admit, hey guys, look, I’m great at this stuff, this stuff right here, I need your help. So let’s do it. And with that open honesty and that mindset, it really helps shift everything around for that unit.

Brett McKay: So Dan, we talked about some great concepts in your book. Is there anything that we missed that you’re really passionate about that you hope people will get out of it?

Daniel Zia Joseph: The biggest thing that’s on my mind is the suicides that happen with veterans and with active duty service members. Leaders can do so much to just approach the job with a sense of humanity, a sense of kindness, a sense of love for their troops that doesn’t stop their tactical abilities. It enhances it. And this isn’t something I’ve necessarily just come up with on my own. This is something people who’ve been to war have told me. They said the purest feeling was being in a war zone, where the number one concern is, did everyone make it back from that movement, from that patrol? Is everyone intact? Is everyone here? Are they present? Are they okay? These service members that I got to work with and these friends that I’ve just… I’m so pumped that I was able to learn from them. And they just… They told me to focus on the relationships, because when you do that, you give people the resources and the tools to handle all the struggles in life that come home with them, where they’re not around their buddies, they’re not connected with others necessarily, but they understand how to handle it. They see their value, they see their capacity to overcome and that resilience stays true. So I would say the biggest takeaway is if you’re a leader, please don’t be afraid to look into what we consider the softer side of human relationships.

Because counterintuitively, it will not stop you from being a savage tactically, to being able to crush whatever physical feat is before you. But I just see sort of this trepidation about approaching leadership that way, because people don’t wanna seem vulnerable and weak. And I understand that, but do the research. Look at the psychological implications of connecting with people in that deeper level because it will save lives.

Brett McKay: Well, Dan, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Daniel Zia Joseph: I have a website, CombatPsych.com, they can go to. And the book is on Amazon, Backpack to Rucksack, insight into leadership and resilience for military experts. And they can just put my name on there, Dan Joseph.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Dan Joseph, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Daniel Zia Joseph: Thank you, appreciate it.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Dan Joseph. He’s the author of the book Backpack to Rucksack. It’s available on Amazon.com. You can find more information about his work at his website, CombatPsych.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/military mentors, where you find links to resources where we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Make sure to check out our website at ArtOfManliness.com where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles that we’ve written over the years about pretty much anything you think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM Podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code Manliness to check out for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android iOS and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AOM Podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to the AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.