When you think of wartime prison escapes, what comes to mind? Probably the breakouts attempted by prisoners of war during World War II and the movie The Great Escape. But the escapees of WWII learned many of the tricks of the trade from their pioneering predecessors, who honed their courageous craft during the first World War.

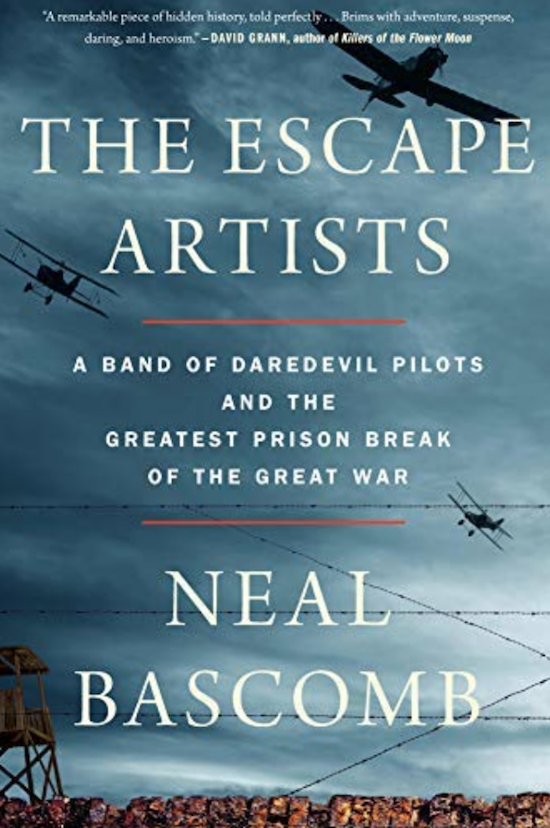

My guest today has written a book about their audacious exploits. His name is Neal Bascomb, and his book is: The Escape Artists: A Band of Daredevil Pilots and the Greatest Prison Break of the Great War. Today on the show, Neal describes what conditions were like for British POWs during WWI, and why prisoners wanted to escape the German camps, even when they were relatively comfortable. We also discuss Germany’s most infamous POW camp, which was essentially a land-locked Alcatraz designed to hold the most escape-prone prisoners. While it was believed to be impossible to escape, Neal describes how the prisoners hatched an elaborate breakout plan anyway, and made a 175-yard tunnel towards freedom. We end our discussion with what Neal took away from the heroic exploits of these men.

You’re going to really enjoy this look at a fascinating slice of history.

Show Highlights

- How Neil stumbled upon this incredible story

- The interesting role of aviation and airplanes in WWI

- The ragtag band of pilots that originally made up the RAF

- The insane danger of being a pilot in WWI

- What led to militaries taking prisoners rather than killing soldiers at the outset?

- Why POW camps in WWI weren’t the torturous environs we know from WWII and Vietnam

- How escape attempts actually contributed to the war effort

- Common escape tactics in WWI

- What made Holzminden a particularly bad place to be

- Some of the escape artists who were in Holzminden (and why Neal calls it “Escape University”)

- The extraordinary tunnel that was dug by the prisoners

- Why actually escaping was the easy part of a prison break

- What happened to the escapees afterwards

- Takeaways Neal took from writing this story

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Great Escape

- My first interview with Neal about the 4-minute mile

- The Escape from Alcatraz

- MI9

- My interview with Winston Groom about WWII’s famous aviators

- How to Plan an Escape from a POW Camp

- My interview with Candace Millard about Churchill’s experience as a POW

- The Most Daring Escape of WWII

- Holzminden POW camp

Connect With Neal

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Slow Mag. A daily magnesium supplement with magnesium chloride + calcium for proper muscle function. Visit SlowMag.com/manliness for more information.

Indochino offers custom, made-to-measure suits at an affordable price. They’re offering any premium suit for just $359. That’s up to 50% off. To claim your discount go to Indochino.com and enter discount code “MANLINESS” at checkout. Plus, shipping is free.

ZipRecruiter. Find the best job candidates by posting your job on over 100+ of the top job recruitment sites with just a click at ZipRecruiter. Visit ZipRecruiter.com/manliness to learn more.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another addition of the Art of Manliness podcast. When you think of wartime prison escapes, what comes to mind? Well probably the breakouts attempted by prisoners of war during World War II, thanks to the movie The Great Escape. But the escapees of World War II learned many of the tricks of the trade from their primary predecessors who honed their courageous craft during the first World War.

My guest today has written a book about their audacious exploits, his name is Neal Bascomb, and his book is The Escape Artists: A Band of Daredevil Pilots and the Greatest Prison Break of the Great War. Today on the show, Neal describes what conditions were like for British POW’s during World War I, any why prisoners wanted to escape the German camps even when they were relatively comfortable.

We also discuss Germany’s most infamous POW camp, which was essentially a landlocked Alcatraz designed to hold the most escape prone prisoners. While it was believed to be impossible to escape, Neal describes how the prisoners hatched an elaborate breakout plan anyway, and made a 175 yard tunnel towards freedom. We enter our discussion with what Neal took away from the rogue exploits of these men.

You’re really going to enjoy this look at a fascinating slice of history, after the show’s over, check out the show notes at awin.is/escapeartist.

Neal Bascomb, welcome back to the show.

Neal Bascomb: It’s great to be back, thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: So we had you on about a year ago to talk about your book, The Perfect Mile, which was about Roger Bannister and John Lindy and Wes Santee racing to be the first man to run a sub four minute mile.

Which kind of, we timed it just right, Roger Banister died a few months after. I don’t want to say we talked about, but it was a great time, people got to learn about Bannister, it was kind of synced up which was nice, people learned more about his legacy.

Neal Bascomb: Exactly.

Brett McKay: You got a new book out though, called The Escape Artists: A Band of Daredevil Pilots and the Greatest Prison Break of the Great War. And for those of you who don’t know, the Great War is World War I.

This book was a fun read, it read, it was an action adventure story, there was comedy, suspense, it had it all. Before we get into the details of it, how did you find out about this ginormous prison break that happened from this POW camp in Germany that was pretty much impossible to escape from, because I never heard of this story.

Neal Bascomb: Well I’ve always wanted to write an escape story, it’s just the Escape from Alcatraz was one of my favorite movies growing up, and the sort of escapades that go into it and the planning and the disguises and everything was just fascinating to me, as a teenage boy.

And so I always wanted to write one of these stories, but I was searching for the right one. An editor of mine wanted me to write about the Stalag Luf escape, the Great Escape of World War II, but that ground had been fairly well tread. And so I was looking for something else and I finally ended up reading this book about MI9 which was the World War II escape and evasion service of the British.

And in that book they note this escape that happened in the previous war, World War I at a place called Holzminden, and it turns out that those people who executed that escape became the teachers and the professors of MI9, and that was the sort of hook that grabbed me, I wanted to learn about this original escape, and the further I plumed into it, it just turned out to be an amazing story.

Brett McKay: Yeah, so you mentioned The Great Escape, I’m sure a lot of people have seen the movie with Steve McQueen jumping over the fence on the motorcycle, looking cool.

Neal Bascomb: Very cool.

Brett McKay: And as I was reading this book, I mean, I was like, I’m reading the prequel of The Great Escape. It almost, they way they did it and we’ll talk about how they did it, it basically set the standard of how these guys in World War II were planning prison escapes.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah I mean the escape at Holzminden was really the road map for The Great Escape that we all know of.

Brett McKay: All right, and so what’s great about this story too is that not only is the escape itself just fun and there’s so many interesting things about it, but you use it as a backdrop to explore other facets of World War I that a lot of people aren’t familiar with.

For example, I mean, the subtitle, it’s the Daredevil Pilots in The Greatest Prison Break. World War I was the first war where aviation played a role. By this time, planes weren’t that old, ten years maybe? What were militaries doing with planes that they had during the first war?

Neal Bascomb: Yeah, I mean the planes at this point in time were essentially made up of wood, wire and some canvas. They were not terribly safe, they were constantly plummeting from the sky, engines were ceasing up, and the generals in charge really didn’t think that they would be terribly useful, I mean one general called it a useless and expensive bad, another thought that they’d maybe need one or two planes but that was about it.

But it quickly, they began to find that they were very useful in consonance and artillery observation, not to mention bombing German targets deep behind the lines.

Brett McKay: How did they do the bombing? Because I guess they had to develop the technology for how do you drop a bomb from the air.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah, I mean, originally again just to show you how antiquated these were, air to air combat was done with rifles initially. Bombs were dropped straight from the cockpit, and it wasn’t for a while during the war they began using dropping them out of the focile lodge. It took a while.

Brett McKay: Yeah I mean I think you talk about too, they have grenades and just-

Neal Bascomb: Exactly.

Brett McKay: Throw it, throw the grenade.

Neal Bascomb: Throw them over the side of the cockpit.

Brett McKay: Right.

Neal Bascomb: It’s rather ridiculous.

Brett McKay: And so the British Air force, what was the state of the British Air force at this time compared to the German? Did one have superior air power over the other?

Neal Bascomb: I mean generally the Royal Flying Co. or the British end of things, and then the German Air force, they were trading places throughout the course of the war. They were constantly adapting technology, they were building faster planes with more fire power and also training their pilots better.

So you’d find at the beginning of the war, the Germans were stronger, but as 1915 came along, the British started to gain momentum and then back again to the Germans sort of taking over things in late 1916, where a lot of these pilots that I feature in the story really come to be captured by the expense of the German flying squadrons that just overwhelmed them.

Brett McKay: So yeah, as soon as they found out that these airplanes had a role, they had to start ramping up production of the airplanes, but they had to put pilots in there, and there weren’t a lot of pilots at the time, so how did they man these airplanes they were building?

Did they just kind of like, hey, you want to be a pilot? Here’s two hours in the air, okay you’re a pilot. What was that like?

Neal Bascomb: Well the original pilots of the Royal Air Force were essentially amateurs, people who owned their own planes, who showed up with them and said, I’m willing to fight for my country.

But of course, they need more and more pilots as more and more of them are shot down. And so they initially started to recruit them mostly from the sort of Harrow, Eaton, Oxford, Cambridge sort of elite people, as my subtitle says, were daredevils, but people who rode motorcycles fast.

It was rather a ridiculous sort of training, recruitment process. They would ask potential pilots who their favorite poet was, do they like solitude, was Kipling or Stevenson a better poet.

Brett McKay: What was the right answer to that question?

Neal Bascomb: Yes, it was Kipling, actually.

Brett McKay: Okay, of course.

Neal Bascomb: And Shelley. Just so you know, over Meredith. They liked football players over pianists, again, it was a rather ridiculous recruitment process but over time who exactly were the best pilots.

And their training methods were both extremely dangerous, half of the pilots were dying over the course of the short training that they received before they were finally sent into mainland Europe to fight.

Brett McKay: So yeah, this was a dangerous job, it attracted a certain type of person. And the other issue with these things is that you’re behind enemy lines typically because you’re doing reconnaissance, you’re doing bombing runs, so you’re more likely probably to be taken prisoner, is that correct?

Neal Bascomb: Absolutely. In 1916 where many of these pilots were captured, the lifespan in the air was 17 minutes long over enemy lines. So you were liable to be shot down in less than a quarter of an hour. And many people died and many of the pilots were actually captured.

And just to give you an idea of sort of how things were at the time, some of the pilots asked for parachutes because that seemed like a good idea, and their bosses in the Air Force said well we want you to be able to be motivated to die, to fight to the very last, and so they were not given them.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and the other thing they had to do too you talk about, is they would, as soon as they crash landed, if that’s what they could do, they were ordered to destroy the planes as quickly as possible so the Germans couldn’t learn about their technology.

Neal Bascomb: Exactly. And so their initial instinct of course was to run for the hills, but they had to destroy these planes. Then by the time that happened they were generally surrounded.

And the fact of the matter was is that they were given absolutely no training in what to do if they were shot down behind enemy lines, nor were they provisioned in a way that they could escape and evade.

Brett McKay: So during World War I, these guys were learning on the fly and this would later serve soldiers in subsequent wars?

Neal Bascomb: Absolutely.

Brett McKay: Right. Well I mean this is another interesting concept that lot of people don’t realize, is this idea of being a prisoner of war, taking prisoners of war, was a relatively new concept.

For most of human history, the rule of, the law of war was if you conquered an army you either killed them or enslaved them. Now, I think the first time they actually started using prisoners of war on mass scale was during The Boer War.

Neal Bascomb: Correct.

Brett McKay: You saw Winston Churchill, we did a podcast with Candace Millard about Winston Churchill’s experience as a prisoner of war, but now we see it at even more mass scale during World War I.

I mean, what caused the nations to decide, we’re not just going to kill people when we take them capture, we’re not going to enslave them, but we’re just going to put them up in a camp. How did nations agree on that?

Neal Bascomb: Well it was a long time coming, and there was a lot of brutality and a lot of death prior to that. I think probably one of the sort of more grizzly stories that you find is this Byzantine Emperor who captured about 14,000 prisoners, he had all but a hundred of them blinded and he left he last hundred blind in only one eye so they could march back to their hometown.

You find that over the course of time, in the 17th century, Dutch legal theorists came up with this idea that maybe we should have rules and laws about killing an enemy on the field and then you find in the Age of Reason, that prisoners were considered okay, these are just men, we don’t have the right to take their lives.

And so again, over time, Abraham Lincoln, codified in the Army Field Manual what to do with prisoners of war, there were Hogan mentions in 1899 and 1907, that also tried to quote unquote, “civilize war.”

And that really lead you to World War I where there were rules in place and obligations for countries to humanely treat the prisoners that they took, but they had no idea what they were going to face in World War I, this industrial warfare were you have millions of soldiers pitted against each other, and so the consequence of that is of course you have millions of prisoners.

And so you find that Germany and the allies were overwhelmed with the vast populations of people that they were taking in and having to house and feed and control. And this led to a lot of problems, both in terms of disease but also in terms of just ill treatment.

Brett McKay: What was a typical prisoner of war camp like, let’s say in Germany? Because I think when most people think POW, they think, I don’t know, I always imagine the Vietnam War or John McCain or Stockdale in solitary confinement in iron shackles.

The way you describe it in the book, it was bad, I’m not going to downplay how it’s not great to be a prisoner of war, but it wasn’t like, what was that, the prisoner of war in Vietnam?

Neal Bascomb: The Hanoi Hilton.

Brett McKay: Yeah, Hanoi Hilton, right?

Neal Bascomb: Right. I mean it’s a great question, it was largely a question of who you were more than anything else. If you were an enlisted soldier you were essentially put into what was a tent city in Germany, where there could be 30,000, 40,000 prisoners held within a certain confinement.

And these prisoners were largely used as workers, put in arbiters commandos to dig mines, to haul equipment and do all other kinds of work that the Germans couldn’t do themselves because most of their people were up on the front.

And then you sort of separate that of course from the officers which was a very different world. In some ways, in many ways, I was surprised at how quote unquote, “cushy” life could be for an officer who was imprisoned.

I mean they were put in largely into barracks of former officers of the German army, they were given orderlies to attend to their meals, they were allowed even what was called to walk on parole, which was they could sign a card saying I vow not to escape and they could walk outside the prison walls and on their gentlemanly code, not escape.

That is not to say again, that life was cushy, and it largely again depended on who the commander was, and what district they were in Germany.

Some were in places where they were well treated, and others particularly in the case of this story, of Holzminden, they were put in a place and commanded by a man named Karl Niemeyer who was just an absolute tyrant and made their lives a hell.

Brett McKay: Yeah we’ll get to Niemeyer here, because he was a character. But the distinction between officers and just regular enlisted soldiers also played a role in who tried to escape from these prisons.

What would happen, if say just a regular enlisted soldier tried to escape from one of these German prisoner camps, compared to say if an officer escaped?

Neal Bascomb: Well if an enlisted solider tried to escape he was either shot while trying to escape or he was placed back into an arbiters commando that was particularly grueling.

So a salt mine or some other sort of heavy labor place where the chances of dying from that were very high. So it was, World War II and the Nazis, they were obviously very brutal to their prisoners, but there was some predecessor to that in Germany during World War I.

Brett McKay: All right, so enlisted soldiers shot or put back in worse conditions, they got recaptured. What would happen if say an officer escaped and got recaptured. Same fate? Or was he treated better?

Neal Bascomb: No, very, very different fate. I mean some of them were of course shot while trying to escape, but the large preponderance of them were placed back and often into the same camps that they escaped from, put into isolation, and there were even rules between Germany and Britain about how long you could put these officers into isolation.

Was it two weeks at a certain point in time, it was a couple months at another point in time. So again, a threat of death was not nearly as high as if you were an enlisted soldier, which of course if you look at the percentages many more officers tried to escape than enlisted soldiers.

Brett McKay: Right, and a lot of these officers you talk about in the book, they were, they made several escape attempts. Reminded me again of the Steve McQueen character in The Great Escape, keeps on trying to escape, gets thrown back into the clinker, gets out, tries to make another escape, I mean these guys were doing, why were they?

Because they wanted their personal freedom or did they feel like it was their duty as an officer to sort of muck things up for the Germans, so their escaping contributed to the war effort?

Neal Bascomb: Yeah, I think, you find over the course of reading these letters that these prisoners wrote, and their memoirs subsequent to their escape, the motivations were pretty much all over the place, many of the of course just wanted to get back into the fight, they wanted to get back to England or their country and get back into the fray.

Others of them considered okay, they might not be able to escape, but every man, every expense that the Germans have to expend on keeping prisoners was one less resource that they had to put into the war. And a lot of it was just this sheer sense of shame that they had, which was unwarranted, these prisoners had of being captured.

The ethos at the time was that you shouldn’t be captured. And so there was this sense that they had somehow not done the proper thing, and so they wanted to sort of right there that wrong by escaping.

Brett McKay: That sense of British gentlemanly honor was driving them.

Neal Bascomb: Exactly.

Brett McKay: What was the most common, we’ll talk about the tunneling, tunneling was a popular approach, but besides tunneling, what was the most common way to escape from these POW camps during World War I?

Neal Bascomb: Well they tried everything under the sun. I mean, the level of hi jinx that went into some of these escapes is absolutely comic.

Some tried to build an airplane at the top of their barracks, others tried to erect a balloon to carry them over the walls, many tried to do the sort of standard cutting through the fence, or jumping the fences, others tried to disguise themselves as German officers and just walk right through the front gate.

Others tried to hide themselves in the garbage bins that were hauled out beyond the walls. If it could be thought of, these prisoners thought of it and attempted it.

Some buried themselves under the ground with a little reed to breathe in, waiting for the guards to go to sleep and then trying to escape that way. It was comic, at many times heartbreaking in others.

Brett McKay: Yeah, you mentioned a few cases where they got just within a few miles of I guess Holland, right? Was where they were trying to go?

Neal Bascomb: Yes.

Brett McKay: A few miles and right there they got captured. And they had to go all the way back. And it’s just like, oh, man. I can’t imagine how that felt.

Neal Bascomb: Well that was the thing, you’re exactly right, the thing was, it was one part to escape the camp, to get beyond the wall, it was quite another, many, most of these places were hundreds of miles from the Dutch border where they could find freedom.

So not only did they have to escape the prison, but then they had to make their way through enemy occupied territory to reach the border. And again, like you said, I mean quite a few of them got within a stones throw to the border and were nabbed.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that’s the thing I noticed as I was reading is that, they got really good at escaping, they could get out, they were masters at that. But it was evading was the hardest thing.

And like you said, they received no training on how to evade the enemy behind enemy lines, so they were just making this stuff up as they went.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah they were, I mean they had to make their own compasses. They had no maps about where they needed to go, how to avoid particular military installations, and the fact of the matter was is that the Germans employed almost a whole population to be on the lookout for escaped prisoners.

So you’d find in many instances POW’s who had escaped are nabbed or spotted by school children and rounded up.

Brett McKay: So there are these officers, always trying to escape for different reasons. The really brazen ones and the bold ones, and the ones that got really good at it, seemed to all end up in this one POW camp called Holzminden, is that how you pronounce it?

Neal Bascomb: Holzminden.

Brett McKay: Holzminden. Tell us about this camp and why was it so hard to escape from.

Neal Bascomb: Okay so you have all these prisoners right? And the large majority of prisoners of course didn’t try to escape, you only had this sort of select few who were trying again and again and again to break out. And as you said, many of them were successful and then nabbed at the border.

So at a certain point, the Germans decide, we need to do something about these escape fiends, as they called them, these people who keep trying and trying and trying, we need to put them all into one place, we need to make sure that place is heavily fortified, heavily overseen by security and make sure that they never escape.

And so they come up with this place called Holzminden, which was south of Hanover and was formerly an infantry barracks that they then surrounded by this almost like a Russian nesting dow, with a stone wall and then inside that a high fence, inside that a no mans land, and inside that another fence, and so it was seemingly, as I called it, kind of landlocked Alcatraz and they decided in the fall of 1916 that all these troublemakers should all be placed in this single prison and that they should be overseen by a particularly cruel Kommandant.

Brett McKay: Yeah so tell us about this guy, because he’s interesting, he’s German but he has an American connection.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah, his name is Karl Niemeyer and I mean, he was the best way I describe him, he was a bully of the first order, just had this terribly rash temper, he was thin skinned, the prisoners called him everything from a cad to a bloated pompous crawling individual, to a cheat, to the personification of hate. And his background was sort of very foggy.

He served in the military, Prussian soldier, he just moved in one story to Milwaukee, served as a bartender, in another story he lived in New York and made billard tables.

People weren’t quite sure what his background was, but he did speak English, he spoke it to a certain extent, although he mauled the language continuously which was both of an object of derision by the prisoners as also a hilarity.

And he found himself in World War I back in Germany, and he with his twin brother Heinrich, overseeing camps, prisoner of war camps in Germany.

Brett McKay: And how did he treat these guys? I mean obviously these guys were put into a camp that was very hard to escape from, and what would he do to officer’s once they got recaptured? Would he do the typical two weeks of solitary confinement? Or would he punish them even more harsh?

Neal Bascomb: He would harangue them, he would strip them of their clothes, he would put them in isolation, and isolation by the way was not something that you necessarily wanted to be placed in.

I mean you could be put in a sort of underground small cell with no exercise without seeing anybody for weeks and months on end, and go mad. And many prisoners went absolutely delirious in isolation.

So for the most part, he just abused and put these prisoners in isolation, and on some rare instances like the man that I call the sort of British Houdini, who was eventually escaped from 12 camps before he got into the hands of Niemeyer, and he was eventually shot in the back and stabbed by bayonets.

So Niemeyer was not against violence by any means.

Brett McKay: And he’d often punish the entire camp whenever there was an escape made, preventing them from exercising, stopping mail, things like that.

Neal Bascomb: Locking them in the barracks. And then that kind of camp wide punishment, that wholesale punishment was against the Hague conventions that purportedly the Germans ascribed to.

Brett McKay: Yeah I mean and these officers, these British officers, they would complain about it but nothing happened.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah, letters were snuck out, prisoners who made it to Holland and back to England and reported about what was happening at Holzminden and to the war office, they knew about it but there was really nothing they could do. They could do the same to German prisoners but that really wasn’t going to happen.

Brett McKay: All right, so what’s kind of funny, is they put these escape fiends all in the same prison thinking, oh, this is a really hard prison to escape from but actually that kind of backfired on them, because you’ve got all these guys who are really good at escaping together in the same camp, where they could mastermind together to come up with the ultimate escape.

So tell us about some of the men or these escape artists as you call them that got placed in Holzminden.

Neal Bascomb: So you’re exactly right, I mean Holzminden became what I call an escape university. So you have all these prisoners who have escaped in various different ways, who had learned different methods, and you put them all into one place and they just feed of each other and learn from each other so if you ever wanted to know how to make a secret hiding spot, you got someone who’s an expert in that.

You want to make a makeshift compass, there’s someone to do that, if you want to know how to smuggle in supplies or tailor a German uniform or pick a lock or engineer some elaborate construction, there is someone at hand, at Holzminden who had done it before, who had been trained in this way.

And so, you have this just collective of people, most of them were pilots, they were all officers, one of my favorites was the Canadian Lieutenant named William Kokuhan, who was six feet six inches tall and went by the nickname Shorty because when he was captured by the Germans, they asked, are all you Canadians so tall? And he said well, they call me shorty.

And this is just the certain nature of these guys, another of them was a man named David Gray, he was an army zapper, he was this sort of stiff military guy, didn’t like to get his uniform dirty, but became a very good aggressive pilot and was one of the sort of leaders of this new plot to escape from Holzminden.

Brett McKay: And you also had the guy that I was really intrigued by, Bennet I think, he was the poet?

Neal Bascomb: Well you have Harvey, who was a poet and one of the sort of great war poets, and then you also have William Bennet who was actually a naval observer who was an expert in hiding catches and all the like. So there was, I mean there were just absolutely a range of people, officers who liked to dress up in drag and escape. I mean you just have the gamut.

Well and then you also have the pink toes, who were this group of officers who were expert tunnelers, and they were called pink toes because their feet were constantly soaked in water and so they became known as the pink toes.

Brett McKay: So all these guys get together, they’ve made different escape attempts while they were there, but then they decided to do this tunnel, which was a long, long tunnel.

How did they all get together and agree that this was going to be the thing that would allow them to escape? What was better about this escape plan than the other plans?

Neal Bascomb: So I think the first reason they needed to, as soon as these guys get into a camp, David Gray or Shorty or Bennet, they survey it. They look around and try to figure out what are the weak spots in the security at this place? And Holzminden after weeks of such surveillance, they couldn’t figure out any way to get out of there.

And so the idea of a tunnel of actually going underneath the ground seemed like really the only way that they could manage it. The other part, the other reason that a tunnel was so attractive was the reason that so many of these men were there is because their typical escape, where they’re cutting through a fence or going through the front gate in a rush or picking a lock, is the people, the Kommandant and the officers overseeing them know immediately that they’ve escaped, and so a manhunt is immediately dispatched and typically they’re rounded up within less than a few hours.

But if you build a tunnel and you escape at night, you have a head start, 12 hours potentially, even six hours where you can get away into the countryside and at least have a fighting chance of reaching the border.

So the fact that Holzminden was otherwise impossible to escape from, and be the fact that a tunnel allowed them to get a head start, was this sort of combining factors that made it so attractive.

Brett McKay: And how long of a tunnel do they have to dig?

Neal Bascomb: Well it seemed like a great idea at the beginning, because they thought that it only needed to be 15 yards long.

They thought that all they needed to do was go from the basement of one of the barracks, underneath the wall which was quite close, and then up out of the hole and then off they go. But the problem was, just about the same time they finished that 15 yards, the Kommandant Niemeyer put a guard almost on the exact spot that they planned on emerging from.

And so it then became a situation where the only way to use that tunnel was to go a hundred and fifty yards to a field where they could emerge unseen and get away.

Brett McKay: All right, so a 165 yard tunnel, basically.

Neal Bascomb: Correct.

Brett McKay: Okay, that’s crazy, I played football in high school, a hundred yards is really long. I’ve crawled on my hands and feet, bear crawled, a hundred yards, and that was terrible, I can’t imagine picking your way, and what did they, how did they do this without getting detected?

How did they not make any noise? What did they use for tools? How did they keep the thing supported? How did they know how to build a tunnel?

Neal Bascomb: I mean it was absolutely horrifying, this situation that they faced while building this tunnel, and I remember even writing it and thinking to myself, God, I could never have done this.

I mean essentially you have them going into this tunnel, digging through the dirt with spoons, the end of a bed stand, and again, they’re not building a tunnel as you probably imagine a tunnel, where you can stand up and walk through it, or even crawl on your hands and knees.

I mean you literally, it was so small that you could barely lie flat without your back touching the top of the tunnel and your elbows touching the sides. So they were essentially just creating a small a burrow as they could because the amount of excavations of dirt and stone, they couldn’t hide, plus it would just take longer.

So you have these men, they go in, they’re digging away, they haul supplies, haul dirt out with a sack and they continued onward. And the deeper they get, the staler and the less oxygen the air has, that then they have to create bellows or feeding air into the system, and it could collapse at any moment, there was dirt constantly falling in your face, down your neck.

And at any moment you could basically be interred and killed, and it was particularly for one of the men, Casper Kenard who was the pilot, he was a claustrophobe and he hated confined spaces, and yet he’s down there, he wants to escape so badly, he’s down in this dark, dank tunnel, illuminated by a single candle, hacking away at the ground ahead of him.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I got claustrophobia. Just reading it.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah, that wouldn’t be good.

Brett McKay: It wouldn’t be good. And besides the officers, did other people in the camp know that there was a tunnel? Was it an open secret?

Neal Bascomb: It was, I wouldn’t call it quite an open secret as much as it was something that the officers, there was this small cabal of men, so there was this core group of 12 officers, and the head of the tunnel David Gray was called the Father of the tunnel, wanted to keep it small.

But the fact was, is that you needed some of the orderlies, some of the enlisted men to help them not only because they needed supplies but because the entrance to the tunnel was actually in the orderlies quarters underneath their quarters in the basement, so they needed uniforms from them, so a few of them knew and then as you get further along the story, and months pass, more and more people are brought in because more and more supplies and information and people needed to be in on the know, so at the end of the day you had like 50 people who actually knew about the tunnel, out of a group of about 600 officers.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and even German guards knew about it.

Neal Bascomb: Even some of the German guards at least knew something was in the works. They had bribed some of the officers, in fact one to provide them with acid to melt the iron rod foundation.

Brett McKay: So as we mentioned earlier, escaping was the easy part, what I think was different from previous escape attempts, that these guys really thought hard about evading this time.

So what were their plans to evade their captors, from being recaptured again after they escaped?

Neal Bascomb: Yeah I mean I think this is what made this the greatest escape of the great war, is not only sort of cleverness of the tunnel but the amount of forethought and planning and effort that went into how they’re going to make this 150 mile run to the border.

One of them planned on dressing up as a business man and taking a train the whole distance, others had mapped out a particular route that they could travel by night and hunker down by day.

And I think probably my favorite story, and the sort of the heroes of these stories, David Gray and his partners Cecil Blaine and Casper Kenard decide the most genius plan which was, every time I think about it I kind of chuckle to myself, but Gray and Blaine would be disguised as orderlies from an insane asylum and Kenard would be acting like an escaped lunatic, and if they were stopped by a local policeman or a German officer, Kenard would go into a sort of apoplectic fit and Gray who spoke German fluently along with five other languages could tell the officers what the deal was and typically they found that people wanted to usher them out of town as quickly as possible.

Brett McKay: Right, right. I mean what I thought was really fascinating, not only do they have a workshop, and they had this system for the tunnel, but they created workshops for tailoring clothes, disguising, they had workshops to make forged documents, photos, et cetera, and they did this again, not knowing exactly what they were doing and they did this without getting caught.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah I mean, they had again, this escape university, so you have experts in all these different fields, and one of the sort of most important ones was a man named Dick Cash who was this Australian enlisted soldier, he was in his mid 40s, he had all his teeth had been knocked out when he’d been blown sky high on the front.

But he was a photographer and he smuggled in supplies to provide not only photos of the officers, but most importantly, duplicates of maps that they needed to make the run to the border. And so all these players were essential. And this couldn’t have happened if the Germans hadn’t placed all these sorts of experts into one place.

Brett McKay: Right, like I said, it backfired on them. Big time.

Neal Bascomb: It did.

Brett McKay: How long did the whole plan take from okay, we’re going to dig this tunnel, to we’re totally escaped? What was the time frame there?

Neal Bascomb: About six months.

Brett McKay: Six months. That’s a long time.

Neal Bascomb: They thought, that’s a long time to keep a secret, it’s a long time, they thought they’d be out by Christmas, they started in basically November, they thought they’d be out by Christmas, but the fact was, they put the extra guard there and then they ran into trouble along the way, the tunnel reached a sort of wall of stones that they couldn’t get through for a long time.

And then there were times where, that their entrance that they used to reach the tunnel was shut down, they couldn’t use it anymore, so they needed to find another way to actually reach the tunnel that then they could dig form.

So there was lots of back and forth, lots of near moments where the tunnel was discovered but they eventually in July of 1918, made the break.

Brett McKay: And how many officers escaped that night?

Neal Bascomb: So you had 29 men actually made it out of the tunnel, over that night before it collapsed, on some of the officers while they were trying to make their ways through.

Those officers were eventually pulled by their heels out of the tunnel but Niemeyer discovered it that morning. Of the 29, 10 made it to Holland and freedom, and they were paraded as heroes and in England the King visited them, honored them and their escapades were splashed across the news because it was kind of a triumph against very great odds, it played very well in a moment that was very dark in the war.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I liked one of the guys, he’s the one that disguised himself as a business man, and took the trains all the way to Holland, as soon as he got there he wrote a telegram, sent a telegram to Niemeyer and was like, hey I’m in Holland, if I ever see you I’m going to break your neck.

Neal Bascomb: Yes, and that was Colonel Rathport, I mean he was quite a character as were many of these people.

Brett McKay: Right and the insane asylum guys, that rouse worked for them.

Neal Bascomb: That absolutely worked, I mean they were almost captured in one town and Kenard went into a fit and they fed them a fake drug which was basically asprin, and he calmed down and they just wanted to get him out of there as quickly as possible.

They barely made it across the border and were shot at as they ran off, but they made it.

Brett McKay: Did all these guys go back to the battle after they escaped?

Neal Bascomb: Yes they all, they were essentially brought back to England, took a little time off and the majority of them went back and rejoined, the majority of them went back and joined the RFC or their units, but the war was almost in its last lengths at that point.

Brett McKay: Yeah it ended shortly after that. And as I was talking about, these guys, they set the example of how to do a POW escape, like how did the British military, and you can also say, I mean I imagine the German military learned from this experience, Americans learned from this, how did they codify what these guys did on the fly?

Neal Bascomb: So once these, even during the war, these prisoners would, if they escaped, and they were brought back, they wrote testimonies of what life was like, and if they escaped they wrote testimonies of how they escaped. And many of them wrote sort of memoirs that they never published.

And then you find that World War II comes along and the British start this service called MI9 which I mentioned before, this gave an evasion service. They decide that a lot of people were taken prisoner in World War I, a few of them escaped, what can we do about it?

And the officers who were put in charge of starting MI9 said, well we need to talk to the experts. And the experts were the people from World War I and many of them were the Holzminden escapees.

And so they went to them and these men particularly William Bennet, a naval observer, became a professor, a sort of secret professor going from air base to air base, given a slide lecture, teaching pilots and soldiers and naval officers and men what to do if they ever found themselves captured.

And it ended up helping quite a few of them escape some famously in The Great Escape and in Holzminden, but thousands of others who you’ve never heard of who got back to their families because of Holzminden and what these men did.

Brett McKay: I’m curious, as you were researching and writing about these escape artists, did you take away any life lessons? Like was there something about these guys that inspired you and you’re like, I should try to develop that sort of attribute that these guys manifested with this experience.

Neal Bascomb: Well I think, my takeaways first this idea of what is freedom. These officers were in a place where okay, they were in some ways had it pretty, pretty nice. They had people making them tea in the morning and polishing their boots.

But the fact that they had no control of their lives, no control of their schedule, what they ate who they slept, where they slept, called, sort of cause what Harvey the poet said was a kind of moldiness which was ruining their soul, and this idea of what is freedom, what is essential in humanity was something that I sort of carried away, particularly Harvey’s insights into that.

And I think the other one that was key to this story and sort of one that I took away was the idea of comradery. David Gray, the Father of the tunnel, tried to escape multiple times and had essentially given up until he found himself at Holzminden and decided that he needed to depend on other people, he needed to depend on his friends to make it out and to make it through. And those are the ones that got him through the darkest hours and he never would have escaped nor would the others if they hadn’t done it together.

Brett McKay: I love that. Well Neal, is there someplace people can go to learn more about the book?

Neal Bascomb: I think there is. They could go to Amazon, their local bookstore, they could go to my website, nealbascomb, N-E-A-L B-A-S-C-O-M-B dot com.

Brett McKay: Neal Bascomb, thank you so much for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Neal Bascomb: Awesome, great to be back.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Neal Bascomb, he’s the author of the book The Escape Artists, available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about Neal’s work at nealbascomb.com. Also check out our show notes at awin.is/escapeartists where you can find links to resources, and where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast, for more manly tips and advice make sure to check out The Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com, and if you enjoy the show, you got something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you’d give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps out a lot.

If you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member, if you think they could get something out of it. Text them a link to the show, send them an email, bring it up in conversation. As always, thank you for continuing to support, until next time this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.