War is about many things: glory, violence, courage, destruction. But at its heart is death. Each side in a conflict tries to kill as many of the enemy as possible, while avoiding being killed themselves.

The way these deaths have played out over thousands of years of warfare has changed not simply based on the way martial technology has changed, but also on the way that the psychological and cultural pressures that have led societies and individual men to fight have changed.

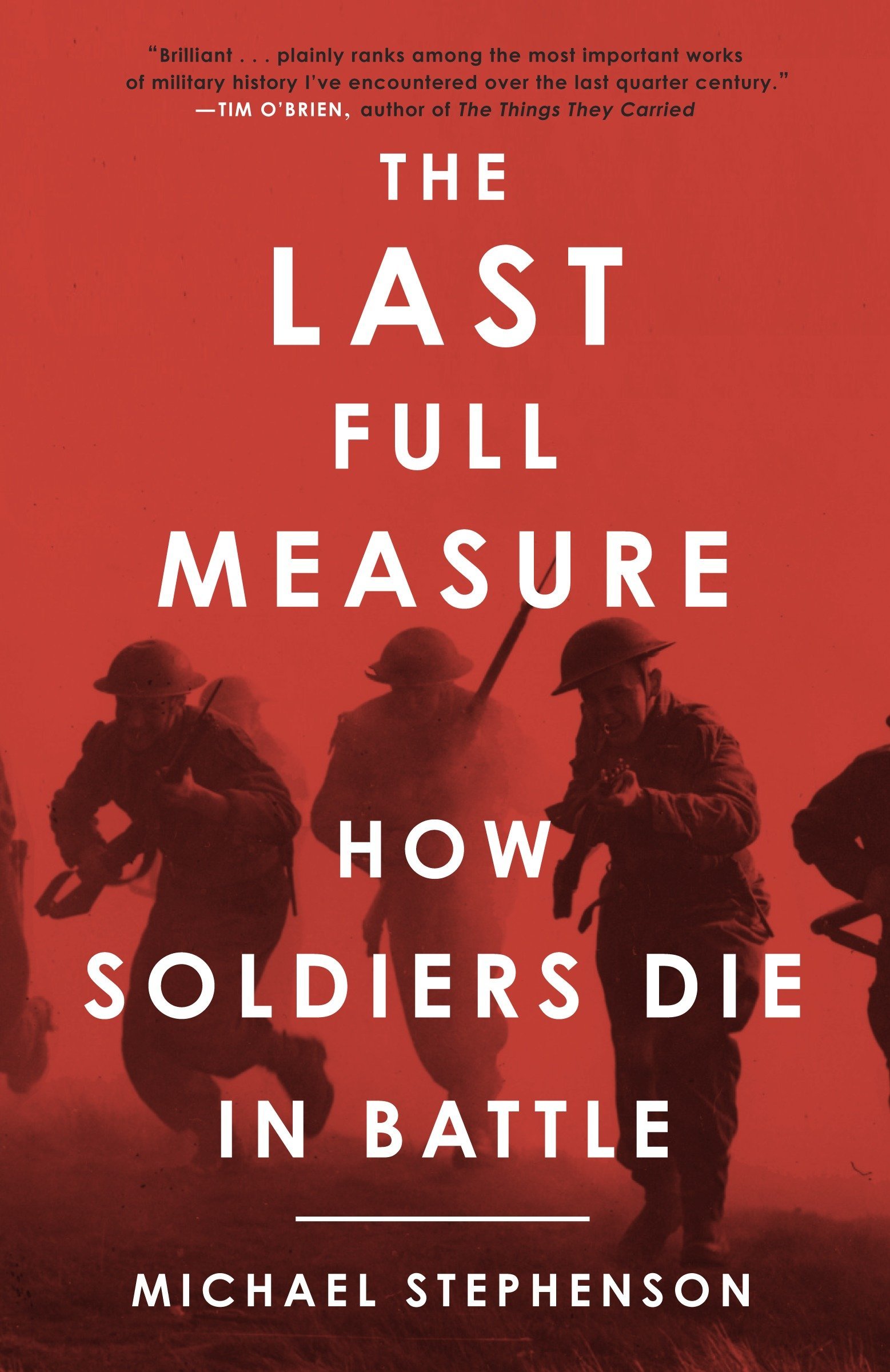

My guest today, Michael Stephenson, is a military historian who explores these evolutions in his book The Last Full Measure: How Soldiers Die in Battle. Today Michael and I discuss the forces that led soldiers to their fate over the centuries, from advancements in weaponry to the expectations of social class. At the beginning of our conversation Michael discusses why he wanted to write this book, and the balance he had to walk in trying to describe the reality of death on the battlefield, without conveying those details in a sensationalistic or titillating manner. We then trace the history of death in war, beginning with its primitive beginnings and working our way to the modern day. Along the way we discuss how gunpowder changed the nature of warfare, the effect that distance has on how heroic a confrontation seems, why artillery is particularly terrifying, what motivates soldiers to fight, and much more.

This is a surprisingly enlightening and humane look at an oft glossed over aspect of the human experience.

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- What makes writing and talking about this topic a challenge

- How do cultural forces impact how people die in war?

- How long have humans been at war?

- What was ancient warfare really like? What was the cause of most casualties?

- What about medieval warfare?

- How gunpowder changed battle

- The terrifying nature of artillery

- The transition from ancient to modern war

- Why do men keep going into battle?

- What were WWII’s amphibious assaults like?

- How modern warfare is actually a bit of a throwback

- What’s the larger takeaway from this discussion?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Greatest Battle of the Korean War

- The Worth of War

- The Spartan Regime

- The Mask of Command

- The Audacious Command of Alexander the Great

- The History and Future of America’s Special Forces

- AoM series on honor

- Men of Legend: The Battle of the Alamo

- Essential Lessons From Great Wartime Leaders

- The Importance of Having a Tribe

- The Kill Switch

- Continuing the Mission of Service and Brotherhood

- The Curious Science of War

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. War is about many things: Glory, violence, courage, destruction. But at its heart is death. Each side in a conflict tries to kill as many of them enemy as possible while avoiding being killed themselves. The way these deaths have played out over thousands of years of warfare have changed not simply based on the way martial technology has changed, but also on the way that the psychological and cultural pressures that have led societies and individual men to fight have changed. My guest today, Michael Stephenson, is a military historian who explores these evolutions in his book “The Last Full Measure: How Soldiers Die In Battle”.

Today, Michael and I discuss the forces that led soldiers to their fate over the centuries, from advancements in weaponry to the expectations of social class. At the beginning of our conversation, Michael discusses why he wanted to write this book and the balance he had to walk in trying to describe the reality of death on the battlefield without conveying these details in a sensationalistic or titillating manner. We then trace the history of death and war, beginning with its primitive beginnings and working our way to the modern day. Along the way, we discuss how gun powder changed the nature of warfare, the effect that distance has on how heroic a confrontation seems, why artillery is particularly terrifying, what motivates soldiers to fight and much more. This is a surprisingly enlightening and humane look at an oft glossed over aspect of the human condition. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/lastfullmeasure.

Okay. Michael Stephenson, welcome to the show.

Michael Stephenson: Thank you.

Brett McKay: You published a book: The Last Full Measure: How Soldiers Die In Battle, which is a historical survey of human warfare and specifically how soldiers die in battle. I’m curious what kickstarted that research project of yours?

Michael Stephenson: I was working as the editor for the Military Book Club in New York, and I was reading a ton of military history. But it seemed to me that quite often, what was missing was a real understanding of what actually happens on the battlefield. Sometimes we have a kind of generalized and rather fuzzy view of it sometimes filtered through movies or through novels sort of. And I wanted to find out because it seemed to be important to honor those people who gave their lives by understanding exactly how it happened. And so I set out to try and trace it as far as I could through the centuries in order to get a sense of what was different but also, perhaps, what connected these things, what connected the experience of being in combat. And I was much more concerned about the combat experience than I was about… I mean, most soldiers who died in warfare died from disease. But that wasn’t really my objective. I wanted to find out if you’d like what happened at the sharp end.

Brett McKay: And at the beginning of the book you noted that was… You were walking a tightrope with this book. What made writing this book or about this topic a challenge?

Michael Stephenson: I think it was that… You’re writing about something that is by its nature gruesome. Whether you’re talking about men being killed in the Greek phalanx or being killed by an IED in Iraq, this is gruesome stuff. But I think that it needs to be understood without it somehow becoming just another part of the sort of pornography and violence that attracts quite a lot of people to this subject.

Brett McKay: And how did you go about making that balance as you were writing this. I mean, were there moments where you thought that, “I gotta pull back,” or were there moments where, “I had to go a little bit further than maybe I want”?

Michael Stephenson: It is hard because if you don’t actually lay out what happens in battle in all its gruesomeness, you’re not really getting to the truth of the experience. But on the other hand, you don’t want it just to be a sort of gore fest. And so… Actually, it just comes down to making individual decisions whether the examples you use of how soldiers are killed progresses the argument, or whether it’s just thrown in just to be titillating. And I hope… Well, I tried very hard not to let it be the latter and more the former.

Brett McKay: I think you succeeded with that. As you were researching, what factors were you looking for to figure out how soldiers die in combat, how it’s changed throughout history?

Michael Stephenson: Oh, I think it’s kind of specific in the sense that there are lots of factors that bring the soldiers to their death. Partly, how does weaponry affect the ability to… What’s their lethalacy of a weapon? What are the tactical contexts in which those weapons are used? And then something that’s a bit harder to pinpoint, but it’s important, what are the cultural drivers that lead men into battle and determine how they act in combat? That’s a harder thing but in the way a kind of more interesting thing because you can trace the development of weaponry through the centuries and see, “Do I have to be face-to-face with somebody in order to inflict a mortal wound or can I do it from a mile way?” So that can be traced quite easily. It’s much more difficult to trace, to chart if you like, the social and cultural influences.

Brett McKay: And we’ll probably talk about some of those cultural and social influence, but what’s an example that people might have heard about that might contribute to how someone dies at war?

Michael Stephenson: I suppose, it’s partly about what society expects of the warrior, what the society who is sending the man into battle would expect them to do. So I suppose for a Greek citizen fighting as a hoplite in the phalanx, it might be very different from, say a GI fighting in Iraq. And it’s complicated to think about that. I mean, one of the issues about the book is it’s such an enormous chronological spread. So that what motivated a Greek citizen to fight in the hoplite would be somewhat different from say a man being conscripted into let’s say, the US Army in World War II, or in Vietnam.

Brett McKay: Now, that makes sense. I mean, as you said… This is a comprehensive historical survey. You start… You try to go back as far as you can. And so do we know when humans started battling each other in an organized fashion?

Michael Stephenson: Yeah. Well, I guess that… Well, some historians say it was about 400,000 years ago, when hominids… There must have been tribal conflicts… But I think in terms of when recognizable weaponry comes in, it’s probably about 40,000 years ago, where you have the atlatl which is a sort of spear, but a projected one. It’s not just hand thrown as it must have been when humans were hunting animals they had spears and they threw them or stabbed them. But the atlatl comes into history about 40,000 years ago, where men could actually throw dart-like missiles. And then 20,000 years ago you have the bow and arrow which ups the ante. But I would imagine that it starts, and it’s quite interesting, I think it starts probably through territorial conflict. And I think, as far as we know, the object obviously, is to win but to win without suffering too many casualties yourself.

So in fact, the earliest warfare, this is my feeling about it, is not what we might call heroic warfare, it’s not sort of charging man to man, it’s more to do with ambushing because with ambushing you get a high reward and with a much lower risk to you, the ambusher. And what’s fascinating is that this early model, if you like, is really what we experience in very modern warfare where guerilla warfare is probably the predominant mode of combat at the moment. And it’s the same kind of idea that ambush whether it’s using IEDs or in ancient and prehistoric times, it would just be obviously sticks that were hardened, fire hardened sticks, or spears, or thrusting-at weapons gave you the advantage of surprise. And also to be hidden from your enemy, it’s very important.

Brett McKay: No. I mean, you make the point that that idea of ambush and raids is an Eastern type of warfare. You even see it amongst Native Americans, that was their preferred method of fighting.

Michael Stephenson: Well, it’s interesting this, because when you look at it from a Western perspective, this form of warfare which you’ve described: Eastern, North American, Native Americans was despised by Europeans and White North Americans because it was considered to be cowardly. So when the Crusaders, for example, are invading Palestine and the holy lands, they are deeply frustrated that the Muslims that they’re fighting won’t actually just come up front and fight them. They use horse archers to torment them. They try and draw out small units of European knights in order to cut them out. And it’s interesting that, for example, US cavalry men fighting Indians in the 19th century, make the same kind of comments about their opposition that the Crusaders did about the Muslims they were fighting in the 12th century.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s talk about this rise of this Western attitude and tactics towards warfare and this seems to have developed with the ancient Greeks. And you point out the Greeks warfare… There’s two ideas about what warfare was like for the ancient Greeks. On one side you have this idea that ancient war was ruthlessly violent with high casualty rates, but then there’s this other argument that ancient Greek warfare was actually just more of a ritualized shoving match.

Michael Stephenson: Yeah.

Brett McKay: What did your research find?

Michael Stephenson: I think both actually. This is the problem. Both of those things can be… They’re not mutually exclusive. So you can have the ritualized shoving match, which can be pretty bloody, particularly for the warriors who are in the front two or three ranks. I mean, what tends to happen is this, there’s a face off usually between the opposing sides. And then there’s this is very interesting kind of dynamic, and maybe that’s not quite the right word, a kind of lightning strike, where one side decides to really start moving forward. And they start to pick up speed, and they want to get through the killing zone, the missile killing zone of arrows, and spears as quickly as they can and to lock in with their opponents. And that can be very bloody in the front ranks. But I think at some point, it’s a little bit like how animals fight. At some point, one side decides that that’s enough and it must be a very extraordinary experience because I think it’s just somehow communicated through the ranks that “we are losing”, or “we are winning” and they give way. And the point in Greek warfare, which is pretty common up until fairly modern times, is that it’s about the ground you can claim. And that gives you the victory. Not necessarily that you’ve inflicted more casualties because you might not have, but they might just have decided that that was enough.

And in Greek warfare, you have two really conflicting ideas. One is that the phalanx, which is made up of citizen warriors, they value their lives because they have to go back. They’re farmers, they’re traders or whatever. They value their lives. They don’t want to give their lives away in some sort of crazy blood fest. So, they’re willing to make kind of compromises. And yet, from what we understand, through Homer or in The Iliad is that you have this idea of the individual warrior, this individual hero who goes and does battle with his peer. And so, this is considered and it is a very profound model for the Western idea of warfare. And actually not just Western. In Japan, it’s true as well. And actually, amongst North American Indians, it’s true as well. The leader has to proclaim himself.

In The Iliad, all we learn about are the names of the great warriors, Hector and Patroclus and so on. We don’t learn the names of anybody else. And so, throughout history, it seems to me that one of the things that’s fascinating is the idea of the individual who can sacrifice himself and be remembered by his name. Think of the medieval knight with his proclamation, if you like. The Samurai warrior, with the same kind of proclamation that, “I am an individual. I will be remembered by my name.” And then, all the rest who are dumped into mass graves at the end of the battle.

Brett McKay: So, we’ve been talking high level with the ancient Greeks and how their tactics may have influenced how they might have died in battle. But specifically, do we have any idea of what was the cause of most casualties during ancient Greece?

Michael Stephenson: I think probably most casualties were caused by spear wounds and sword wounds. But actually one of the things that is overlooked a little bit is that this was a huge number of people coming together and a lot of people were simply crushed. They were crushed because the two armies come together, they’re both pushing against each other, the rear ranks are pushing forward and pushing the people in the front ranks forward who then trip, fall and are suffocated. This is true, certainly in Medieval warfare. It’s certainly true in Greek warfare where you have such a large number of troops in a small area. So, it’s not usually thought of much, but I would say that that was a contributory factor.

Brett McKay: And something that you note with the Greeks and the Romans, this carries through to them even the Medieval era. But purely, the Romans and the Greeks, they used weapons like artillery, missiles. But at the same time they had a disdain for it. They thought it was less manly or less virile.

Michael Stephenson: Yeah. I think this is a very interesting point actually because I think that… Okay, so the heroic model, if you like, is set up by one man fighting another man. That might be one heroic leader fighting another man, whether it’s Greek or whether it’s the Medieval knight. But as weaponry develops, their missiles become more and more important. So for example, you do not find a Medieval knight using a bow and arrow. And there’s a certain disdain for it because it’s connected in a way to a kind of social context. For example, the idea that somebody who just happens to be trained as say an archer or a cross-bow man could kill a nobleman from 200 yards, 300 yards or whatever with a cross-bow, actually a lot longer than that. It was considered to be deeply immoral. And so you find in up to, I would say up to the 18th century, this idea that somehow missile warfare is unfair because it robs the nobleman, it robs the socially privileged of their honor. And for example, in the 15th century, if you were a cross-bow man and you were captured, there was a paper decree that said that you… Well, often they would often just be killed, but that you would have one of your hands chopped off so that you couldn’t do that again. So, there was a deep mistrust of missile warfare as being non-heroic.

Brett McKay: So listen, you mentioned the Medieval knight that they still had this idea of the single man going out and doing battle. And that’s typically when people think of Medieval warfare, they think of that. They think of the knight in armor riding on a horse. But you highlight that’s not how most of medieval battles went. There were other people there fighting as well.

Michael Stephenson: Yes.

Brett McKay: So, who were those people and what was a Medieval battle like?

Michael Stephenson: I’ve got a feeling that most battles whether it was Greek or Medieval, where it comes down to men with axes, with swords, with hammers, often with agricultural implements that have been adapted to warfare, what happens is a sort of absolutely appalling scrum. So, as you know, the knights very often didn’t fight on horseback. They fought dismounted. And even if they were fighting on horseback, they were very vulnerable or once they were dismounted. The misconception is, of course, of the knights were so heavily armored that they couldn’t move. They were like sort of turtles that have been turned on their backs, which is not true. The armorers were incredibly skilled and these knights had a lot of mobility. But nevertheless, they could be swarmed. Swarming a knight was usually the way in which they died and they could be stabbed through the thighs. There were all kinds of vulnerabilities, through the armpits, through the crotch. Just being hammered.

In Agincourt, the French Knights who managed… Because of their hubris managed to, and also it was a very muddy battlefield, managed to get mired in the mud and the English archers who had mallets. They were called mauls, which they used to hammer in the stakes from behind which they would be protected went out onto the battlefield and literally beat the Knights to death. And it was appalling, and it wasn’t at all heroic. And you can imagine the catastrophe of a scrum of knights all writhing around in the mud being set upon by all of these men of course, these villeins as they were called, who they despised and so at Agincourt for example in 1415, Henry V has this rather difficult decision to make. He’s captured a lot of French Knights. And normally, the protocol would have been that these knights would have been spared and ransomed. But then he’s told that it’s suspected that there’s another French force coming and his concern is that he has this bunch of French knights, some hundreds in his rear as captives. And if this French force somehow links up with them, he would be in a very difficult position, so he gives permission for his archers to kill the Knights. And this is considered an absolute abrogation of the chivalric code, but he does it anyway.

Brett McKay: Well, that’s another interesting point that you bring up throughout the book is the treatment of prisoners of war. Because we think it’s sort of a given now, which we’ve had the Geneva Convention for most of the 20th century, but for most of human history, there was just basically, “give no quarter” was the rule.

Michael Stephenson: I think it’s often the rule. I don’t think it happens always but there are plenty of examples of it, of prisoners being killed out of hand in modern warfare. I think, in the heat of battle all kinds of things happen. We would like to think that men behave with some kind of humanity and often they do. And one of the things that moves me very much is reading accounts of soldiers who kill an enemy and then have this realization that it could have been them. What I mean is that there’s a connection of a shared humanity, which is devastating to some of these soldiers, and yet, it’s full of contradiction. You have that, you have this devastating sense that you’ve done something that is absolutely irrevocable and irreparable. You’ve taken somebody’s life.

And then there are other men who just think it’s great. They have a great joy in killing. So yes, there’re all kinds of so-called conventions about prisoners of war, but they’re often breached and breached for all kinds of reasons, a bit like the reasons that I said about Henry V in Agincourt because it’s just safer. For example, in the First World War, if there were trench raids, you did not take prisoners. You got into the first trench and you killed every man there was in that trench. I mean, the wounded, it doesn’t matter. You killed them all because you couldn’t have the possibility of these people suddenly being a threat to you in your rear. So, they had to be killed. And that was just one of the facts of that kind of warfare.

Brett McKay: So, up through the Medieval era and then I guess starting the 17th century, the 18th century, you see the introduction of firearms, gunpowder. How did that change warfare?

Michael Stephenson: Well, I think, what use is the knight if all of that armor can be breached by a ballistic missile fired by somebody from 10, 200 yards away? And so, from about 1600, what happens to the armored knight? It’s interesting. In the English Civil War, which is the 1640s, you still have noble soldiers in pretty much full armor. For example, of the Battle of Edgbaston, the Duke of Northumberland is unhorsed and they have to… He was a Royalist. And the parliamentary soldiers who unhorsed him have to actually take his helmet off in order to chop his head off. But when you look at that period, the 1640s, very few noble soldiers are wearing armor. Buckskin. Mobility is much more important. So, buckskin. Yes, they wear a helmet as we still do today but you do not see the armor or the knight in full armor anymore because the gun has revolutionized the battlefield.

Brett McKay: But you know, it took a while for the gun to actually make a significant difference ’cause early firearms were incredibly inaccurate.

Michael Stephenson: Yes, they were. Yes. Right up until I suppose, mid-19th century. They were pretty inaccurate in the American Civil war. And I think one of the things is not just about whether the weapon itself is accurate and often up until… What are we talking about, the 1870s, the 1880s, they were pretty wildly inaccurate. But it’s also about what happens in the context of a battle, in the context of combat. So, that you have lots and lots and lots of examples of men who even with rifled muskets in the Civil War, they load them five, six times. Men forget to take out the rammers because it’s such a panic. The stress is so extraordinary that even men with relatively accurate weapons don’t use them properly. So for example, the ramrods. I’m thinking about the War of Independence, particularly. The ramrods are stuck into the earth because you cannot keep putting the ramrod back in its holder in the musket. You just stick it in the earth and you ram it down the musket. And of course, the earth begins after a while to jam it up. And so, even right from the beginning of gun warfare there’s the inaccuracy of the weapon itself and the inability of the soldier to use it properly.

Brett McKay: And because in the early gun warfare, ’cause the guns took a relatively long time to reload, when they were inaccurate, one of the things that commanders did is they basically bunched people up together.

Michael Stephenson: Yes.

Brett McKay: So we’d have rows. And then they basically did warfare like they did it in Medieval times. Just like one side on one side, the other side and the other. And first line would shoot their thing and then the next line would shoot and they kind of reload, but that actually made you more susceptible ’cause people would just aim at that grouping of people.

Michael Stephenson: Yeah, I suppose. But you have lots of occasions where… Here are a couple of things. One is that, people say, “Oh, this is the American Civil War, it’s the highest lethality of any war in history,” which maybe would be true, but then there are lots and lots of anecdotes about how much lead had to be expended to kill a man. I mean, the joke was that you needed to fire as much lead as a man weighed to kill one man. So, you have these two rather contradictory things. And I think what it is, is that if you take the whole picture, you can make an argument that the lethality is not quite as great as one might imagine. But if you take more localized things like certain regiments in certain battles, the lethality is absolutely horrific where you have frontal attacks against prepared defenses. And you’re right, because you had to get men close together to make that discharge count. It could count very horribly if you were close enough.

Brett McKay: The one thing it seemed like, extremely terrifying, this I think goes through even modern warfare when the direction of gunpowder was artillery. Cannon balls. That seemed to be the thing that a lot of soldiers were afraid of the most.

Michael Stephenson: Yeah. Because it’s more spectacular, isn’t it? If you see somebody hit by a cannonball, it’s a very different experience of seeing somebody hit by a Minié ball. I’m talking about some Civil War again, but some… It’s just so much more dramatic. And this is true I think in the First World War and the Second World War. I think what soldiers really feared most was artillery because it’s probably true that in the First World War and the Second World War, artillery was the most lethal thing that soldiers faced. But there’s something else too, and that is you’re completely helpless. To be under an artillery bombardment is to be absolutely without any defense whatsoever. And that was horrifying and I think that’s what frightened most soldiers more than probably any other kind of weaponry.

Brett McKay: And in speaking of sort of the cultural and social influence on how… That influenced the way soldiers died, the point you made, Officers were expected to still lead from the front. They were expected to…

Michael Stephenson: Yes.

Brett McKay: Be cool in the face of battle. And so, as a consequence of that…

Michael Stephenson: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Officers had the highest lethality rate during the 18th-19th Century.

Michael Stephenson: Yes, not just the 18th-19th century, but looking at certainly at world war I, the Officer fatalities as a percentage were much, much higher. So you have this thing which goes way back, doesn’t it, goes way back to the beginning of warfare, which is that… And this interests me quite a lot this… You have a military structure which says, “Here are the Officers and they’re going to lead you. And they are going to take the highest risks, because they’re out front.” And what does that reflect? Up until probably quite recently, up until probably the Second World War. The Officers reflect a social division, the Officers just like the Greek warriors in the Iliad, just like the medieval knight in the 18th century, the Officers represent a social distinction. Now this fascinates me that they aren’t necessarily militarily, the most effective, it’s not the most effective way to deal with things ’cause after all, if your Officers aren’t particularly trained, they can do some pretty damaging things to the men and to the outcome of the battle.

But up until World War II, I’d say, Officers were designated by social class and sometimes and many times they were very effective. Because if you take the medieval knight as representing an Officer, they’ve been trained for most of their life to do this stuff. But it isn’t always true in the sense that to become an Officer in the 18th Century, 19th Century Army often meant you got there because of your social position rather than because of your military training. And I think that broke down obviously in world war I, well, actually it’s primarily true in world war I. The Officer class is still a socially elevated class. World War II, I suppose, breaks it down pretty completely. And I would imagine, now in modern armies it’s almost entirely gone. That it’s… Merit gets you your status as an Officer, rather than social background. Not entirely actually, I’d still say to some extent it’s true today in that if you come from a military background, you tend to come from a certain kind of social class, I don’t know whether… It’d be an interesting thing to look at.

Brett McKay: You make the point with the Civil War, the 19th Century that we start to see this, it’s sort of like a transition point between ancient to modern warfare.

Michael Stephenson: Yeah.

Brett McKay: What happened there, do you think that made that transition?

Michael Stephenson: I think just the lethality of weaponry, but I think in a sense that if you look at it from the very earliest to the most modern, there’s some idea about distance that the heroic is defined by closeness, closeness to your enemy. With North American Indians, it wasn’t necessarily that you had to kill your opponent, but you had to touch him, I.e. You had to get close to show your bravery. Well, you can be killed by a sniper from a mile and a half. You can be killed by an IED, which has been laid by somebody two weeks before and set off with a mobile phone from a mile away. And so that idea of proximity, has evaporated as weapons become more effective from a longer range. And now, we’ve got to a situation in fact, where you don’t actually need people at all, drone warfare and one imagines smart weapons on the battlefield, begin to make the role of the human less and less important.

Brett McKay: Then another… After the Civil War, you had the Boer War in South Africa, which was another transition from sort of that ancient warfare to modern warfare, you see more mechanization and then world war I, that’s noted as the war that ended any romanticization of warfare, that sort of heroic ideal, Hemingway, “The Lost Generation” and all made the case that, world war I just ended…

Michael Stephenson: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Words like courage and honor. What changed? Was it just the pure mechanization, the machine gun, the chemical gas? Was that the thing that just sucked out any sense of…

Michael Stephenson: Oh, I think you’re looking at just being over… Totally overwhelmed by the weaponry available. You have artillery of extraordinary accuracy and massive power. You have mass troops going against machine guns, gas I think is a less, I don’t know, gas I think has a lot of dramatic impact, I’m not sure that it accounts for huge numbers of casualties. I think probably artillery and machine guns were the primary killers in world war I and there’s a kind of anonymity that… It’s shocking to me that when you go and look at the cemeteries in France and Belgium, First World War cemeteries, how many men weren’t even found. The Menin Gate I think has about 50000 names of men who, their bodies were never recovered, artillery simply evaporated them and or buried them or whatever. And this idea of just never even being recovered, it’s just extraordinary. That is, if you want to put it crudely, that is the most anti-heroic way you can be killed in warfare.

Brett McKay: Another thing, you said men, but oftentimes these were boys. These were…

Michael Stephenson: Oh yeah.

Brett McKay: Sometimes 16-year-olds, 17-year-old boys.

Michael Stephenson: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Who died during world war I.

Michael Stephenson: Yeah. It’s interesting this because I think reading quite a lot about world war I which happens to interests me, particularly, I think British people are particularly fascinated by it in a way that Americans aren’t, only in that the losses involved were so much more impactful on British society than they were American society, but the enthusiasm with which these young men joined up, and also this, what you might call the lax criteria there were for allowing young men in, you just lied. You just said, “I was 17 last birthday.” And they go, “Are you sure?” And then, “Yes.” You’re in, but there was great enthusiasm for this war, which actually wasn’t entirely extinguished. I mean, we think that God, if you’ve been through that experience, and yet, a lot of men still held steadfast to their belief in the necessity of the war, and this interests me quite a lot in that what happens I think is that societies construct the scaffolding deep, the ideological scaffolding that is meant to make men want to fight, but actually, once men are in warfare, and they see what it’s like, they create their own internal motivation, and it’s usually attached to their unit, their buddies, their friends and then, they disconnect from the social. These are the reasons why we are fighting men. Get out there.

They disconnect from all that, and that’s why you find in the first of one second World War, why men, actually rather dreaded going back to say, in this… To Britain on leave because they were going back to a group of people who didn’t really understand at all what they were going through, and often, they just wanted to get back to their unit, even though it was going to be a very, very dangerous thing to do because they wanted to be back with men who understood what they were going through, and this is critical, I think, throughout history, that the soldier has to know that what he’s doing is at least recognized, and the only people that usually can recognize it are the people that are also going through what you’re going through.

Brett McKay: Now, Sebastian Junger, the journalist, in his book Tribe, he makes that point as well, and it still happens today. Soldiers get back because… It’s not ’cause they… Not necessarily they believe in the bigger mission for the nation state, but it’s like they want to get back to their buddies.

Michael Stephenson: Well, I think when you look at soldiers who’ve been in Iraq and Afghanistan and in Vietnam, they feel in a way that they’re in a vacuum, that nobody really understands. That’s why PTSD is so appalling, so prevalent, is that they carry this experience inside of them, and they cannot find a way to express it, or so many of them can’t because what have we done? We don’t have conscripts, anymore. We don’t have national service anymore. We just send these professional soldiers out there, and they feel in a way, abandoned, I think, and particularly, when they come back.

Brett McKay: Something that’s interesting about starting… I mean, I would say the 18th century, but particularly in the Civil War, and especially in World War I and World War II, we actually have diaries and letters from men fighting, and as a result, you’re able to see this ghastly picture. Some of these guys got very detailed in explaining how a buddy next to him, one minute, laughing, the next minute, dead, I mean, in a very ghastly way. And I mean, some of the more haunting descriptions you provide in the book, it was, particularly, in World War I, I mean, people forget this about artillery shells. Sometimes they would detonate above you, but the air blast would just devastate your internal organs, and kill you, and soldiers would stumble upon groups of men that just look like they’re just lying. They’ll still look kind of alive, but they’re not.

Michael Stephenson: Well, I think that must have been… That is the weirdest thing because there are accounts not just from World War I, but thinking of an account from the American Revolutionary war, where a cannonball passes so close to a man’s head, that he’s killed instantly without any mark on him at all, and it’s because the shockwave of the balls killed him, and I think it must have been horrifying to come across soldiers who’ve been killed without really any mark on them. Of course, normally, there were plenty of marks, but it was so abhorrent and shocking, but yes, you’re right. You can be killed. There’s an anecdote of a soldier in the European theater in World War II. He’s way behind the lines. He’s in a tent where they’re showing a film. He’s leaning forward with his elbows on his knees. There is a shell burst from a long, long way away, and a piece of shrapnel kills him through the back from two miles away, and it’s as though death finds a way to reach out in some bizarre way that you cannot account for.

Brett McKay: And I mean the other thing that struck me particularly from the letters and diary entries from World War I was just how common death became and it became like just another thing that happened like some you know… I think there’s a journal entry from a British officer where they’re having tea, artillery blew up and you know couple of guys… A guy died and there was blood everywhere and they cleaned it up and they just kind of kicked dirt over the blood and then they kept going with their tea. I mean they became very callous to it because they had to, to survive.

Michael Stephenson: But you know this is part of something else, I mean, I think the anecdote you’re referring to are officers who are taking tea ’cause…

Brett McKay: Right.

Michael Stephenson: That’s you know… It was part of… And I would imagine you’re describing British officers?

Brett McKay: Correct.

Michael Stephenson: But it was part of this social expectation of that class that you did not show undue emotion in a situation like that. You know, there had to be some for… So for example, at the Battle of Waterloo, General Paget is riding alongside Wellington and Paget is hit by a cannonball and it takes off his right leg. And he’s still in the saddle and he turns to Wellington and he says, “My Lord, I’ve just lost my leg.” And Wellington turns to him and says, “Good God, sir, so you have.” And that’s it. Paget actually survives, goes on to father, I think, about 12 children, [chuckle] but you know that idea that you did not show any shock in the face of the most shocking and horrible thing was actually something that your class taught you.

Brett McKay: Alright, moving into World War II, there were new technologies that brought new ways for soldiers to die. There were bomber and fighter planes and parachutists as well as amphibious warfare. And when people think of World War II, they topicality think of D-Day, of Normandy and the way you described it in the letters and diaries from soldiers, there were so many ways to die when invading the beach, sometimes even before you got on to the beach.

Michael Stephenson: There’s an anecdote in my book where one of the landing crafts’ captains, pilots, whatever, just gets into a complete funk and you know they’re being shelled and whatever, and he just lowers the ramp and these heavily, you know, I mean these soldiers are carrying, 60-70 pounds worth of stuff, but he lowers the ramp into 15 feet of water and the men just go over and of course, they drown. And about 20 of men do this until the man behind just say, “I’m not… You know, this is wrong, I’m not doing this.” And so yes, you could, you could drown, you could be wounded and just drown because you can’t struggle anymore. I mean, there’s just a ton of ways in which you can die.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and then you get on the beach, there could be mines…

Michael Stephenson: Oh, gosh.

Brett McKay: You have to worry about artillery shelling, I mean these things you don’t think about and when you think World War II…

Michael Stephenson: Well, I think you know that… You know that… You know Saving Private Ryan, the movie?

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Michael Stephenson: The first 15 minutes or so of that movie are absolutely extraordinary, as an evocation of what it must have been like.

Brett McKay: So that brings us to today, and as you mentioned earlier, we’re starting to see a return to the past of how we’re going back to that guerilla warfare, asymmetrical warfare, and that’s changing the way soldiers die again.

Michael Stephenson: It is and it changes the way in which they feel about their sacrifice, I think, because you know they’re being killed at long distance. You know they’re being sniped, they’re being killed by buried IEDs and mines. They can’t identify their enemy. This comes across as you know, very strongly in soldiers’ accounts of fighting in the Vietnam War, in Afghanistan and in Iraq. What’s the, you know… Who’s the civilian, who’s the enemy, and that feeling of frustration and it’s a double whammy because first of all, you can’t hit back at the enemy, you can’t identify them, and then you’re killing innocent people. That is horrifying to you, horrifying to most human beings. And so where is the heroic confrontation in this? And it’s interesting that in sort of popular culture and I’m talking about popular American culture particularly, no and British culture too, it’s the sniper who is identified as the heroic character and it’s the SEAL or the special operations sort of counter-guerilla fighter who is considered to be heroic ’cause they at least have a chance to hit back.

Brett McKay: And given the fact that facing death and battle throughout history has always been such a terrifying, terrible prospect, how do you think men did it and were able to face it?

Michael Stephenson: I think that they were propelled not by some surge of patriotic energy, you know let’s do this for the motherland, the fatherland, whichever land. But they did it because their buddies expected it of them. My father went to… My father was in the British Army, six years, and I would say to him, “Well, what made you do that? What did you feel? I mean was it that you were passionately anti-Nazi and so on.” And he said, “Well of course, we hated Hitler.” But he didn’t do it for ideological reasons, he did it because there was peer pressure to do it. Oh, my buddies were… My friends were signing up so I signed up. And I think that drives you forward. It’s… And it’s not you know, “I’m gonna be heroic, I’m gonna get out there and I’m gonna take up that machine gun next.” I’m sure there were, you know, there are exceptional human beings who do that kind of thing, but for most people it was… And it moves me terribly when I think about Civil War battles were I’m thinking about the Irish Brigade going up to the hill that Marye’s Heights and they’re under just ferocious fire, and they’re described as pulling their caps down, and bending their heads into the fire, and going forward. Well, that is a kind of heroism that is just beyond words, really.

Brett McKay: Michael, after people read this book, what do you hope they walk away thinking after they put it down?

Michael Stephenson: I hope that there’s some feeling of humanity about this. This book was never written in order to glorify warfare. In fact, quite the opposite. I wanted people to understand exactly what does happen on the battlefield, and I’d hope that… I end the book with a letter from an American Vietnam veteran, and he’s writing this letter which he puts into the Wall of Remembrance in Washington. But it’s written to a Vietnamese soldier whom he has killed, and he’s asking forgiveness for this. And I wanted to end the book on that note, rather than some either triumphal note or some sort of geeky technological look into the future.

Brett McKay: No, I think that for me, it hit on some of the pat… The thing that I got from this was war, it’s a terrible thing, but it’s a very human thing.

Michael Stephenson: Yes.

Brett McKay: And we have to figure it out. It’s something we have to digest and really understand if we really wanna understand ourselves.

Michael Stephenson: Well, I think it goes into the deepest parts of us, and it’s a profound and complicated thing to deal with, and the flag waivers and the jingoists just represent one small and not, I think, very honorable part of it. And I wanted to… And the book has lots of contradictory things in it, but that’s the nature of the business, isn’t it?

Brett McKay: It is. Well, Michael Stephenson. Thanks so much for your time. It’s been an absolute pleasure.

Michael Stephenson: Thank you so much.

Brett McKay: My guest here was Michael Stephenson. He’s the author of the book “The Last Full Measure: How Soldiers Die In Battle”. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Check out our show notes at aom.is/lastfullmeasure, where you find links to resources and we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The AoM podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you’ll find our podcast archives as well as thousands of articles we’ve written over the years about pretty much anything you can think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AoM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code MANLINESS at check out for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS and you’ll start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AoM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcast or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you would think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you all to listen in to AoM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.