This article is part of a series that studies the life of Jack London, and especially his display of the Ancient Greek concept of thumos.

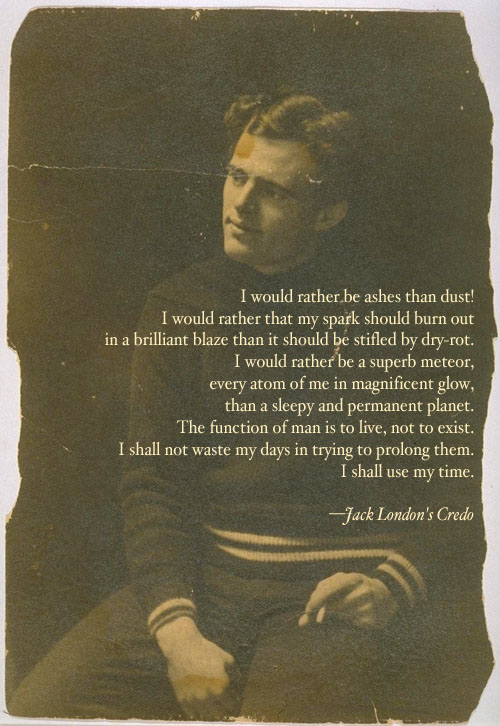

“There is an ecstasy that marks the summit of life, and beyond which life cannot rise. And such is the paradox of living, this ecstasy comes when one is most alive, and it comes as a complete forgetfulness that one is alive. This ecstasy, this forgetfulness of living, comes to the artist, caught up and out of himself in a sheet of flame; it comes to the soldier, war-mad on a stricken field and refusing quarter; and it came to Buck, leading the pack, sounding the old wolf-cry, straining after the food that was alive and that fled swiftly before him through the moonlight. He was sounding the deeps of his nature, and of the parts of his nature that were deeper than he, going back into the womb of Time. He was mastered by the sheer surging of life, the tidal wave of being, the perfect joy of each separate muscle, joint, and sinew in that it was everything that was not death, that it was aglow and rampant, expressing itself in movement, flying exultantly under the stars and over the face of dead matter that did not move.” –Jack London, The Call of the Wild

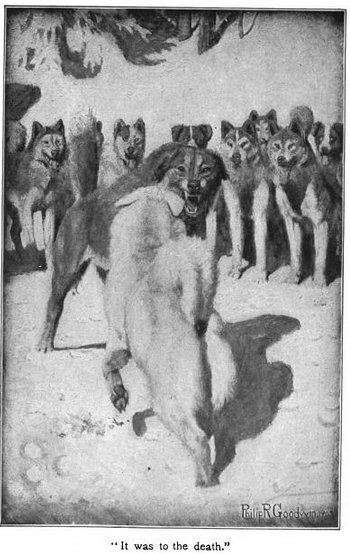

Jack London’s most popular novel, The Call of the Wild, is a tale of a domesticated dog, Buck, who is thrust into the wilderness. He is forced to learn the brutal rules of a new world and how to mush mightily in front of a dogsled, and eventually breaks away to become the leader of a wild wolf pack. Jack said it was a story of “the dominant primordial beast,” and as such it is his story as well. Like Buck, Jack would pass through a crucible of difficulty, learn to thrive and delight in the harness of discipline, and harken to the deep-seated call to become the best of the best. He would outwork everyone else to earn a position at the head of the pack through skill and prowess and fight.

Jack’s fight began soon after he returned from the Klondike. After months of sitting in the “White Silence” of the Great North, pondering what he wanted out of life, he had returned home committed to either becoming a writer or perishing in the attempt.

Forging a Life of Discipline

London sat down at his desk, pulled out his old typewriter, and resumed the life of iron-clad discipline he had embraced while studying for his collegiate entrance exams, which, if you’ll remember, consisted of 5am wake-up calls and 19-hours of daily toil.

Though he had been living in the wilderness for the last year, Jack did not chafe at returning to being holed up in a room from sunup to sundown. One of the things London’s friends marveled at was this great dichotomy of his character – how he could take his unfettered spirit, his fierce thumos, and channel it at will into a rigidly disciplined, unwavering drive for success. As his friend Anna Strunksy put it:

“His standard of life was high. He for one would have the happiness of power, of genius, of love, and the vast comforts and ease of wealth. Napoleon and Nietzsche had a part in him…and it was by the force of his Napoleonic temperament that he conceived the idea of incredible success, and had the will to achieve it. Sensitive and emotional as his nature was, he forbade himself any deviation from the course that would lead him to his goal. He systematized his life. Such colossal energy, and yet…He lived by rule. Law, Order and Restraint was the creed of this vital, passionate youth.”

Yet while London was an ardent “disciple of regular work,” this did not mean that such self-mastery came naturally to him. “Temperamentally,” Jack said, “I am not only careless and irregular, but melancholy.” “Still,” he added, “I have fought both down.” One way he mastered his penchant for irregularity was establishing a fixed goal of writing at least a thousand words every day, six days a week (sometimes on Sundays and holidays too). He wrote to a friend: “I am sure a man can turn out more and much better in the long run, working this way, than if he works by fits and starts.” London would keep this habit of writing 1,000 words a day for the rest of his life, no matter his physical or mental conditions – whether he was tired, sick, hung-over, traveling aboard a ship rocking violently in a storm, vacationing in Hawaii, or covering a war in Japan. It especially did not matter whether he was feeling “inspired” on a given day; London thought the idea of creative inspiration was bunkum – the complaint of its absence an excuse of the lazy and cowardly. Success in writing, or any other vocation, London argued, was all about effort and willpower – “digging” as he liked to put it:

“A strong will can accomplish anything…There is no such thing as inspiration and very little genius. Dig, blooming under opportunity, results in what appears to be the former, and certainly makes possible the development of what original modicum of the latter one may possess. Dig is a wonderful thing, and will move more mountains than faith ever dreamed of. In fact, Dig should be the legitimate father of all self-faith.”

A large part of Jack’s own digging and refinement process involved studying the work of other great writers (Rudyard Kipling in particular) with an eye towards improving his own. Besides developing one’s philosophy of life, Jack considered this kind of study of one’s “mentors” the second great key to success in life. He described his own process through his fictional alter ego, Martin Eden:

“Reading the works of men who had arrived, he noted every result achieved by them, and worked out the tricks by which they had been achieved — the tricks of narrative, of exposition, of style, the points of view, the contrasts, the epigrams; and of all these he made lists for study. He did not ape. He sought principles. He drew up lists of effective and fetching mannerisms, till out of many such, culled from many writers, he was able to induce the general principle of mannerism, and, thus equipped, to cast about for new and original ones of his own, and to weigh and measure and appraise them properly. In similar manner he collected lists of strong phrases, the phrases of living language, phrases that bit like acid and scorched like flame, or that glowed and were mellow and luscious in the midst of the arid desert of common speech. He sought always for the principle that lay behind and beneath. He wanted to know how the thing was done; after that he could do it for himself. He was not content with the fair face of beauty. He dissected beauty in his crowded little bedroom laboratory…and, having dissected, and learned the anatomy of beauty, he was nearer being able to create beauty itself.”

After London had soaked his brain with the elements of great writing he admired, he set about trying to create his own. Jack sought to develop a different style from the popular fiction of the time — work that was full of the “the fancies and beauties of imagination…an impassioned realism, shot through with human aspiration and faith.” He endeavored to capture “life as it was, with all its spirit-groping and soul-reaching left in.”

Day after day London refined his style and dug through his brain, pulling out memories of the raging waves of the Pacific and the harsh cold of the Klondike. He feverishly banged out essays, articles, poems, short stories, and serialized fiction on his rickety typewriter. Except for “breaks” to visit the library, “he wrote prolifically, intensely, from morning till night, and late at night.” Just as Buck learned to pull sleds in the Klondike, Jack “worked faithfully in the harness, for the toil had become a delight to him.” “Life was pitched high” he wrote in Martin Eden. “The joy of creation that is supposed to belong to the gods was his.”

The Sting of Rejection

Unfortunately, the joy he sent out into the world was not reciprocated. Each time he placed a new piece inside an envelope and sent it off to newspapers, magazines, and journals around the country, his heart would swell with hopes that it would be accepted. And each day as he opened his mailbox to see yet another round of rejection notices, his heart would sink. One editor even took the time to write that the quality of his work was such that he really ought to find a different profession. Jack would try to shake off the constant rebuffs, place the rejection notices in a file and the returned manuscripts in a pile of “retired” work, and then begin pounding at his typewriter once more.

Yet, months of rejections coupled with his merciless work schedule slowly began to take their toll – exhausting him both mentally and physically. His skin grew pallid from a lack of fresh air and sunlight. He had to pawn many of his possessions to buy food, and still found himself in debt with the grocer. His cheekbones became more pronounced and his muscles withered as he tried to get by eating as little as possible. His energy and optimism dropped along with his weight, and at times he felt he should give up altogether — not just writing, but life itself. What depressed him most was how lonely he felt – he had no one to help him with his writing or even to simply offer encouragement. As he wrote in a letter to a friend:

“Nor has anybody ever understood. The whole thing has been by itself. Duty said ‘Do not go on; go to work.’ So said others, though they would not say it to my face. Everybody looked askance; though they did not speak, I knew what they thought. Not a word of approval, but much of disapproval. If only some one had said, ‘I understand.’ From the hunger of my childhood, cold eyes have looked upon me, or questioned, or snickered and sneered. What hurt above all was that they were some of my friends—not professed but real friends. I have calloused my exterior and receive the strokes as though they were not; as to how they hurt, no one knows but my own soul and me… for good or ill, it shall be as it has been—alone.”

In spite of all this failure, and as we have seen, true to his character, London would poke at the embers of his determination and find the will to continue striving. He concluded the letter above by saying:

“So be it. The end is not yet. If I die I shall die hard, fighting to the last, and hell shall receive no fitter inmate than myself.”

Success Begins to Make Itself Known

Still, as a hedge against the potential of failure, and to please the family and friends who told him to quit this fruitless writing business and get a “real” job, he took the civil service exams and passed with flying colors. The manager of the post office called to offer Jack a position as a mail carrier. London was conflicted. He had just turned 23 and his friends were settling down, getting married, and starting good professions. Being a mailman would bring decent, steady pay, and his family needed money. He considered continuing to write, but doing so just as a hobby instead. Most sobering of all, he had to face the fact that in his five months of trying, and in sending out almost 50 manuscripts, he had only succeeded in having one piece published, and that in a magazine for children. But his mother, surprisingly, encouraged him to turn the job down – to finally take a chance on his own dreams after years of dutifully supporting the family. They would get by, she told him. So he rejected the offer. London would have no plan B, no back-up day job if success was not soon forthcoming. He would put all of his chips into becoming a writer.

At last, six months after returning from the Klondike, Jack received news that his gamble might just pay off. The Overland Monthly agreed to publish London’s “To the Man on Trail,” and then also accepted “The White Silence.” Jack’s fresh, virile style began to attract notice. “I would rather have written ‘The White Silence,’” the literary critic of The San Francisco Chronicle confessed, “than anything that has appeared in fiction in the last ten years.” The Overland Monthly requested six more of Jack’s articles. They’d paid just $7.50 per piece for them, but as the premier literary journal of the West – one that was read by many movers and shakers in the publishing industry – the deal promised beneficial exposure.

London’s real break came in November 1899, when the Atlantic Monthly decided to publish “An Odyssey of the North.” This piece broke the dam, and at last the publishers came calling. London signed a deal with Houghton Mifflin to put together a collection of his short stories: The Son of the Wolf. After facing so many rejections, the positive reviews brought the sweet music of vindication to Jack’s ears: “These stories are realism, without the usual falsity of realism,” praised The New York Times. “You cannot get away from the fascination of these tales,” The San Francisco Chronicle effused. The public loved Jack’s punchy, muscular prose, and felt as though his stories stirred something long dormant within them. As they read of his protagonists pitting their mettle against the elements of nature, they felt their own call to the wild – a keen desire to have an adventure themselves.

Finally, A Dream Realized

In three years of “studying immensely and intensely,” Jack had made himself into a full-time writer, and more opportunities came his way. A month after The Son of the Wolf was released, Cosmopolitan (which at this time was a well-regarded magazine for the whole family) offered him a plumb position as editor and staff writer. London turned it down without hesitation. Like Buck, after gathering strength in the discipline of the harness, he desired to exercise that strength with minimal restraint and full independence. As he wrote to a friend, “Of course I shall not accept it. I do not wish to be bound…I want to be free, to write of what delights me, whensoever and wheresoever it delights me. No office work for me; no routine; no doing this set task and that set task. No man over me.”

Over the next few years, Jack continued to sleep but five hours a night (“There was so much to learn, so much to be done… I blessed the man who invented alarm clocks”) and his profile continued to rise as he successfully published numerous articles and several short story collections and novels. His books sold decently, but were not blockbusters. Stratospheric success would arrive with the 1903 publication of The Call of the Wild. Jack had intended it to be another of his short stories, “but it got away from me, and instead of 4,000 words it ran 32,000 before I could call a halt.” The novel became an instant classic. Its story reverberated through a society anxious that it had become too refined, too civilized, too domesticated and had lost its rugged, pioneering spirit. Such a theme has pricked the hearts of each succeeding modern generation, and the book has been in print continuously for over a century, sold millions of copies, and become the most widely read of the American classics.

Now 27 years old, Jack London had reached the pinnacle of the literary world. By venturing more and fearing less, by working longer and harder than anyone else, he had overcome his humble past and risen head and shoulders above his peers. By harnessing his thumos, and embracing his identity as the lone wolf, he had made himself stronger and more powerful than the average man. The same thrill of dominance that enlivened Buck coursed through him as well:

“When the long winter nights come on and the wolves follow their meat into the lower valleys, he may be seen running at the head of the pack through the pale moonlight or glimmering borealis, leaping gigantic above his fellows, his great throat a-bellow as he sings a song of the younger world, which is the song of the pack.”

Read the Entire Jack London Series:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Boyhood

Part 3: Oyster Pirate

Part 4: Pacific Voyage

Part 5: On the Road

Part 6: Back to School

Part 7: Into the Klondike

Part 8: Success at Last

Part 9: The Long Sickness

Part 10: Ashes

Part 11: Conclusion

_________________________________

Sources:

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London by James L. Haley

Jack London: A Life by Alex Kershaw

The Book of Jack London, Volumes 1 & 2 by Charmian London (free in the public domain)

Complete Works of Jack London (all of London’s works are available free in the public domain, or you can download his hundreds of writings all in one place for $3, which is just plain awesome)

Tags: Jack London