This article is part of a series that studies the life of Jack London, and especially his display of the Ancient Greek concept of thumos.

When the ship Excelsior docked in San Francisco in 1897, it carried word that would grant Jack London salvation from his mindless toil in a steam laundry: gold had been discovered in the Klondike.

The whole country was quickly seized with gold fever, and Jack was not immune. The North called to him as a chance for adventure, as well as an opportunity to earn the fortune that would finally allow his family to live comfortably, and free him to make a career as a writer without having to worry about the constant press of bills and hunger.

Venturing to the Great North

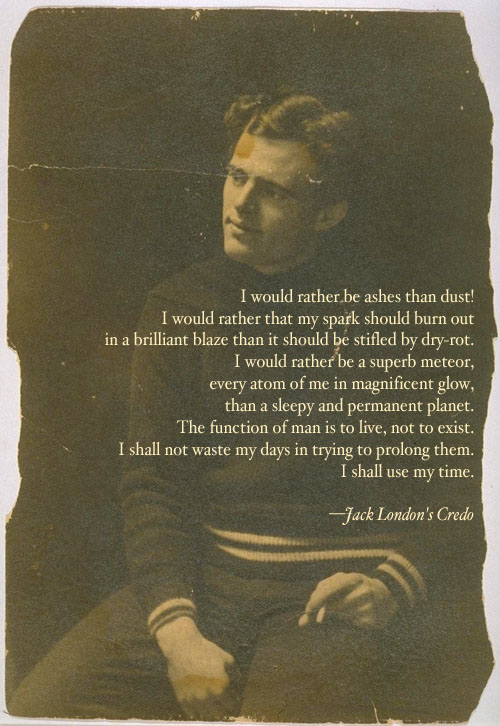

London secured the funds for his venture from his stepsister in return for agreeing to take her sickly 60-something husband along with him. Jack used the money to outfit a nearly 2,000-pound kit of supplies for the two men, and then boarded a steamship for the 8-day voyage up to Seattle and on to Juneau. Once he and his brother-in-law landed, they climbed into 17-foot canoes and were paddled by the natives 100 miles to the Dyea beachhead — a site of complete chaos. Three thousand “cheechakos” — the derisive native term for tenderfeet from the lower 48 — swarmed about. Many in their naivety did not realize that the Klondike was not located anywhere near where their ship would dock, but was in fact situated more than 500 miles to the north in the heart of the Canadian Yukon. Faced with an arduous trek by foot and boat, some men, including Jack’s brother-in-law, turned right around and went home.

Having studied up on the geography of the land and a former miner’s account before setting out, Jack was better prepared than most. He had an idea of what was coming, and knew that the first leg of the journey was a 28-mile uphill hike to Lake Lindeman. Most of the new arrivals had figured they would be able to pay the natives at reasonable rates to shoulder their packs for them along the way. But the indigenous porters, taking advantage of the enormous demand for their services, were charging a hefty thirty cents per pound. With the Canadian Mounties requiring those who wished to cross the border to have a year’s supply of food and equipment, the assistance could cost the equivalent of a man’s entire salary for the year. Without the necessary funds or the physical strength to carry their own supplies, another large cohort of would-be prospectors were defeated before they had even begun.

Not Jack. He had already settled in his mind the physically demanding method he would use to shoulder his supplies himself. He divided up his half-ton kit into around a dozen smaller loads, and would take each load a mile, cache it, and then return for another. This meant that every mile of forward progress required nearly 25 miles of hiking, half of them while shouldering 75-100 pounds of supplies. Jack relished the physical challenge, however, and took pride in his ability to outpace many of the native porters.

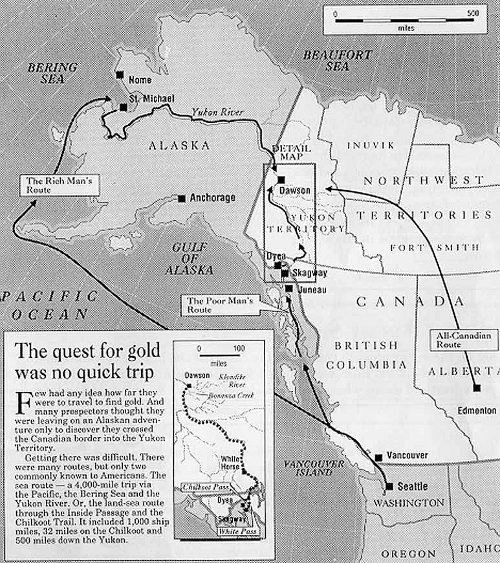

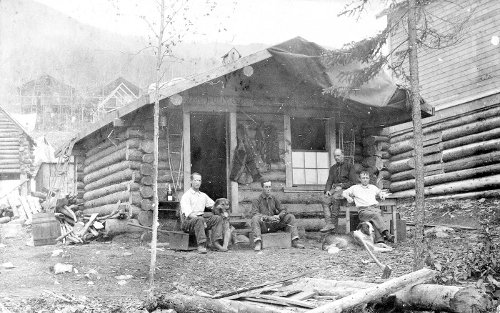

London is thought to be the young man at the forefront of the group on the right. The men are at Sheep’s Camp, a resting place a few miles from the arduous Chilkoot Pass.

For the first six miles, London and several friends he had met along the way were luckily able to pull their supplies along in a boat down a river. Then Jack began his double-back trekking method for the next eight miles, carrying load after load up an incline, through mud and rain, and around boulders. In three weeks the men reached the first rest camp, and there gathered strength for the most arduous part of the trek – a single-file ascent of the Chilkoot Pass.

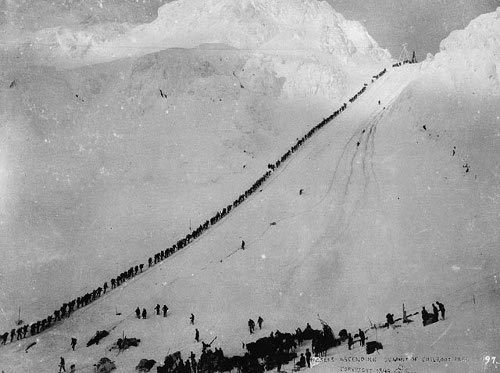

Three-quarters of a mile in length at a 45-degree angle, sourdoughs referred to the Chilkoot Pass as “the worst trail this side of hell.”

Three-quarters of a mile in length at a 45-degree angle, sourdoughs referred to it as “the worst trail this side of hell.” The weaker among the would-be prospectors collapsed. Hordes beat a trail back to Dyea in defeat and others went mad and even shot themselves. Jack simply bore down in determination, put one foot in front of the other, and ignored the burn in his legs and back as he carried a half-ton of supplies to the summit, 100 pounds at a time.

To get his half-ton of supplies to the top of the pass, Jack made around a dozen trips up and back.

From the top of the pass it was nine more miles of trekking through a steep canyon to the banks of Lake Lindeman, the headwaters of the Yukon River. It had been three weeks since Jack left Dyea, but the journey was truly just beginning. He now had to float, sail, and navigate the 500 miles of lakes and waterways en route to Dawson, which sat 50 miles from the goldfields.

If Jack’s physical strength and grit had been an asset so far, now his technical skills and sailing experience became a huge advantage. He and his comrades felled some trees and made two boats to convey them on their voyage. Although he was but 21 years old, Jack’s confidence and skill made him a natural leader, and the older men trusted him to pilot them safely through the treacherous waters. It was a trust greatly tested – Jack chose to shoot the boat over six-foot ridges of water and turbulent rapids, between rocky reefs and sheer cliff walls, and through two powerful whirlpools. The men had seen several boats ahead of theirs broken to bits, their passengers drowned right before their eyes, and most of the other prospectors chose to portage around these man-slaying dangers. But when it came to a choice between several days of portaging or two minutes of running the shoots, Jack chose the latter. Having departed in mid-summer, the early Arctic winter was setting in fast, and they needed to make it to Dawson before the waterways sealed with ice.

Charmian recounts Jack’s feverish race against time:

“By unabating zeal the boys kept just ahead of the forbidding freeze-up that set a bar of iron to the progress of the less forehanded. Lakes froze on their flying heels, so slim was the margin. Jack learned what it meant to pit one’s raging impotence against the imperturbability of nature. Never a waking moment did they lose, and allowed no more time for sleep than was absolutely required…

Their sternest battle was across Lake Laberge, the freeze-up of which threatened in the gale. Three days they had been thrown back by cresting seas that fell aboard in tinkling ice. On the fourth Jack said: ‘To-day we’ve got to make it—or we camp here all winter with the others.’ They almost died at the oars, but ‘died to live again’ and fight on. All night, like driven automatons they pulled, and at daybreak entered the river, with behind them a fast frozen lake. And their pilot, from what I know of him, I can swear did not realize half his weariness, so elated must he have been to be thus forward—one of the very few who had made it through.”

After barely making it over Lake Laberge, London and his partners decided to settle in and hole up in the cabins of an abandoned mining camp. They were just 75 miles from Dawson, but the Yukon River was quickly freezing up. The men figured they’d try their hand where they were; they had encountered discouraged Klondikers on a return journey who informed them that supplies were non-existent for weathering the winter in town, and that the best claims further up the Yukon had already been staked. Jack found a bit of gold dust in nearby Henderson Creek and staked a claim there. A few days later he took his boat to Dawson to register it.

By the time Jack had completed an arduous hike through the snow to return to camp (an experience he would later draw on to write his best short story, “To Build a Fire”), winter had thoroughly set in, and there was nothing left to do but ride it out. When the weather was fairer Jack would venture out to the creek, huddle in an old dugout, and spend the time panning for gold and thinking about life. The impenetrable stillness and silence of his surroundings — what he called nature’s “White Silence” — was overwhelming:

“Nothing stirred. The Yukon slept under a coat of ice three feet thick. No breath of wind blew. Nor did the sap move in the hearts of the spruce trees that forested the river banks on either hand. The trees, burdened with the last infinitesimal pennyweight of snow their branches could hold, stood in absolute petrifaction.”

Such an empty, lonely landscape stirred deep, humbling introspection for Jack:

“Nature has many tricks wherewith she convinces man of his finity, — the ceaseless flow of the tides, the fury of the storm, the shock of the earthquake, the long roll of heaven’s artillery, — but the most tremendous, the most stupefying of all, is the passive phase of the White Silence. All movement ceases, the sky clears, the heavens are as brass; the slightest whisper seems sacrilege, and man becomes timid, affrighted at the sound of his own voice. Sole speck of life journeying across the ghostly wastes of a dead world, he trembles at his audacity, realizes that his is a maggot’s life, nothing more. Strange thoughts arise unsummoned, and the mystery of all things strives for utterance. And the fear of death, of God, of the universe, comes over him, — the hope of the Resurrection and the Life, the yearning for immortality, the vain striving of the imprisoned essence, — it is then, if ever, man walks alone with God.”

When weeklong blizzards raged and the temperature dipped to 60 degrees below zero, Jack hunkered down in his cabin, wrapped himself in thick blankets, and wiled away the time trading stories and debating life’s big questions with his companions. The men’s cabins were a frequent destination for visitors – natives, fellow prospectors, and gritty trappers would stop by to break the tedium of winter. One who met and tested wits with London during this time was W.B. Hargrave, who offers a portrait of London during this time that is worth quoting at length (we even included it in the Manvotionals book), for it truly offers a snapshot of Jack in the very prime of his manhood:

“No other man has left so indelible an impression upon my memory as Jack London. He was but a boy then, in years . . . But he possessed the mental equipment of a mature man, and I have never thought of him as a boy except in the heart of him . . . the clean, joyous, tender, unembittered heart of youth. His personality would challenge attention anywhere. Not only in his beauty for he was a handsome lad but there was about him that indefinable something that distinguishes genius from mediocrity. Though a youth, he displayed none of the insolent egotism of youth; he was an idealist who went after the attainable; a dreamer who was a man among strong men; a man who faced life with superb assurance and who could face death serenely imperturbable. These were my first impressions; which months of companionship only confirmed.

I remember well the first time I entered [his cabin]…One of his partners, Goodman, was preparing a meal, and the other, Sloper, was doing some carpentry work. From the few words which I overheard as I entered, I surmised that Jack had challenged some of Goodman’s orthodox views, and that the latter was doggedly defending himself in an unequal contest of wits. Many times afterward I myself felt the rapier thrust of London’s, and knew how to sympathize with Goodman.

Jack interrupted the conversation to welcome me, and his hospitality was so cordial, his smile so genial, his good fellowship so real, that it instantly dispelled all reserve. I was invited to participate in the discussion, which I did, much to my subsequent discomfiture.

That day—the day on which our friendship began—has become consecrated in my memory. I find it difficult to write about Jack without laying myself open to the charge of adulation. During the course of my life . . . I have met men who were worth while; but Jack was the one man with whom I have come in personal contact who possessed the qualities of heart and mind that made him one of the world’s overshadowing geniuses.

He was intrinsically kind and irrationally generous. . . . With an innate refinement, a gentleness that had survived the roughest of associations. Sometimes he would become silent and reflective, but he was never morose or sullen. His silence was an attentive silence. I have known him to end a discussion by merely assuming the attitude of a courteous listener, and when his indiscreet opponent had tangled himself in the web of his own illogic, and had perhaps fallen back upon invective to bolster his position, Jack would calmly roll another cigarette, and throwing his head back, give vent to infectious laughter—infectious because it was never bitter or derisive. . . . He was always good-natured; he was more — he was charmingly cheerful. If in those days he was beset by melancholia, he concealed it from his companions.

Inasmuch as Louis Savard’s cabin was the largest and most comfortable it became the popular meeting place for the denizens of the camp. Louis had constructed a large fireplace, and my recollections of London are intertwined with the many hours we spent together in front of its cheerful light. Many a long night he and I, outlasting the vigil of the others, sat before the blazing spruce logs, and talked the hours away. A brave figure of a man he was, lounging by the crude fireplace, its light playing on his handsome features—a face that one would look at twice even in the crowded city street. In appearance older than his years; a body lithe and strong; neck bared at the throat; a tangled cluster of brown hair that fell low over his brow and which he was wont to brush back impatiently when engaged in animated conversation; a sensitive mouth, but lips, nevertheless, that could set in serious and masterful lines; a radiant smile, marred by two missing teeth (lost, he told me, in a fight on shipboard); eyes that often carried an introspective expression; the face of an artist and a dreamer, but with strong lines denoting will power and boundless energy. An outdoor man—in short, a real man, a man’s man.

He had a mental craving for the truth. He applied one test to religion, to economics, to everything. “What is the truth?” “What is just?” It was with these questions that he confronted the baffling enigma of life. He could think great thoughts. One could not meet him without feeling the impact of a superior intellect.

Many and diverse were the subjects we discussed, often with the silent Louis as our only listener. Our views did not always coincide, and on one occasion when argument had waxed long and hot and London had finally left us, with only the memory of his glorious smile to salve my defeat, Louis looked up from his game of solitaire (which I think he played because it required no conversation) and became veritably verbose. This is what he said: ‘You mak’ ver’ good talk, but zat London he too damn smart for you.’”

Weakened in Body, Strengthened in Spirit

Two brothers London met in Dawson, or more accurately, their canine companion, would feature prominently in Jack’s future. Louis and Marshall Bond’s dog (seen with Marshall on the left), a huge half collie, half St. Bernard mix, would become the inspiration for Call of the Wild’s protagonist, Buck.

As the long winter wore on, the vitality Hargrave so admired in London began to ebb. His skin grew sallow, his teeth loosened, his gums bled, and his joints ached. Having subsisted on a diet of bacon, beans, and biscuits for months, Jack had developed a severe case of scurvy. As soon as the ice began to break up in the river, he partially dismantled his cabin and built a raft to float to Dawson in order to have himself examined. A priest there who offered medical care ameliorated his condition with some raw potatoes, but he advised Jack to get home as quickly as possible if he valued his life – fresh food was scarce and astronomically expensive in Dawson. Jack being Jack, he still stayed on for a few weeks to soak in the colorful life of a remote boomtown before beginning his journey back to the States. He could have returned the way he had come, but as Charmian put it, “he seldom retraced a road.” Instead, he and a friend decided to pilot a small skiff 1,800 miles down the entire length of the Yukon and out to the Bering Sea. After passing numerous native villages, taking in beautiful vistas, being nearly eaten alive by swarms of mosquitos, and having a whole other set of adventures, Jack arrived at the port of St. Michael, Alaska, and boarded a steamship back to San Francisco. He paid for his passage by stoking coal, until his weakened body finally gave way and the sympathetic crew allowed him to knock off and recuperate.

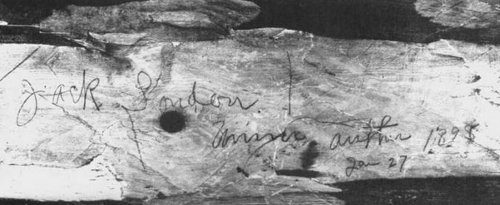

After being away for nearly a year, London arrived back home debilitated and broke; his trip to the Klondike had netted him but $4.50 in gold dust. But the experience had provided him with things far more valuable – seeds that would soon bear spectacular fruit. Most obviously, the adventure burnished him with a cache of rich material that he would mine again and again, spinning his observations of the icy North into bestselling stories that would catapult him to the heights of success. But the confidence to even attempt to transform those stories into literary gold was also born in the Yukon. “In the Klondike,” Jack said, “I found myself.” The journey had taxed his stamina and determination and employed his technical skills — pushing his mental and physical abilities to their limits. It had strengthened the heart of an already powerful thumic confidence and hardened his conviction of making it as a writer. If he could scale Chilkoot Pass, navigate thousands of miles of river, and weather an Arctic winter, he could struggle with words until he had become their master. London was ready to take on the fight for his future, and he had already determined its outcome. Before he left his cabin in the Klondike, he carved this on a beam:

Jack London, Miner, Author, Jan 27, 1898

Read the Entire Jack London Series:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Boyhood

Part 3: Oyster Pirate

Part 4: Pacific Voyage

Part 5: On the Road

Part 6: Back to School

Part 7: Into the Klondike

Part 8: Success at Last

Part 9: The Long Sickness

Part 10: Ashes

Part 11: Conclusion

____________________________

Sources:

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London by James L. Haley

Jack London: A Life by Alex Kershaw

The Book of Jack London, Volumes 1 & 2 by Charmian London (free in the public domain)

Complete Works of Jack London (all of London’s works are available free in the public domain, or you can download his hundreds of writings all in one place for $3, which is just plain awesome)

Tags: Jack London