“Finland alone, in danger of death — superb, sublime Finland — shows what free men can do.” –Winston Churchill, January 1940

“All we had to do was raise our voices a little bit and the Finns would obey. If that didn’t work, we could fire one shot and the Finns would put up their hands and surrender.”

These were, Nikita Khrushchev later recalled, the predictions he and his fellow Russian leaders made on the eve of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Finland in November 1939.

The coming invasion had been planned after Finland’s government rejected demands from their Soviet neighbors to move part of their shared border, cede Finnish land, destroy their fortifications, and lease a peninsula for the building of a Russian military base.

When negotiations failed, the gears of war began to spin, though most of the Soviet brass, especially Stalin himself, felt they would not have to turn long to crush Finland’s precocious opposition.

Conquering the country would amount to nothing more than a police action, and take no longer than two weeks, the thinking went. The Soviet Union boasted the world’s largest military force; Finland, one of the smallest. The former had 3X more soldiers, 5X more artillery, 30X more aircraft, and 100X more tanks. When Stalin looked at the operation on paper, he couldn’t wait to get started with what would clearly be a quick and easy walkover.

Yet what became known as the “Winter War,” did not go at all like the Russians planned.

Essential Guerrilla Tactics from the Finnish Winter War

The mere ten divisions of Finnish soldiers who assembled to meet the half-million Soviet invaders truly had their work cut out for them. Not only were they weaker and smaller in terms of manpower but also in material: much of the weaponry the Finns possessed dated back several decades, and there weren’t even enough of these “antiques” to go around. Stockpiled cartridges, shells, and fuel would only last several weeks, and ammunition had to be rationed both in training and on the frontlines. Finnish tank forces were operationally non-existent, and the military didn’t possess even one fully functioning antitank gun with which to counter the hordes of armored vehicles the enemy sent rolling in. The Soviets had squadrons of several thousand aircraft; Finland, only about a hundred, and even amongst this tiny air force, just a dozen were actual modern fighter planes — the rest of the fleet being made up of slow, biplane artifacts from another era of flight.

Given this enormous mismatch in resources, Finland knew it had no chance of ultimately repulsing the Russian invasion by itself. Rather, it hoped to put up such a fight, and hold out for a long enough time, to either convince another Western power to come to its aid, or, to cause the Soviets such pain and trouble, that Stalin would ultimately decide not to occupy the country, allowing Finland to maintain its independence.

In the latter aim, Finland was shockingly successful.

Rather than taking a couple of weeks, Finland held out for over 100 days. And while the resources of the battling forces were enormously lopsided, so were the results — only in the very opposite direction one would imagine: at the conflict’s end, 70,000 Finnish fighters had been killed or wounded, while 350,000 Soviets walked away maimed, or not at all.

How was this smaller force capable of enduring so much longer than most thought possible, and inflicting such heavy damage in the absence of ample resources?

They kept their resistance effort lean and mean and squeezed every last possibility out of the resources they did have; they knew how to do more with less. They substituted speed for size. They turned seeming liabilities into assets.

In other words, they embraced the timeless strategy of the successful guerrilla warrior.

It’s a method of fighting tailored to the position of the underdog, and its tactics not only apply to the battlefield, but any endeavor in which one’s resources are short and the odds are long. Below we detail many of these tactics, all of which are undergirded by what the Finnish call sisu — a word that roughly translates to “grit,” but that, as we’ll see, embodies so much more.

Make the Environment Your Ally

When a big organization, be it a military force or corporation, moves into a certain space, there’s always one area where they’re at a big disadvantage: they don’t know and aren’t adapted to the environment the way those who are “native” to it are.

When the Soviets marched into Finland, they entered a field of battle that could not have been more inauspicious to a foreign invader.

Finland is checkered with almost 200,000 lakes, intersected by dozens of rivers, and covered with some of densest forests in the world. While every winter is long — daylight lasts for only a few hours — and bitterly cold, the winter of 1939-1940 was one of the harshest on record; temperatures often dipped to 30 degrees below zero.

The depth of the cold, and its attendant and unrelenting snow, made all the regular activities of war significantly more difficult and complicated. A bared hand rapidly developed frostbite, or stuck to the metal of one’s gun. Caloric needs rose. Drugs froze. Blizzards hampered vision and reconnaissance. Weapons jammed. Truck batteries died. Vehicular or foot travel outside main roads was impossible.

The Soviets never fully adapted either tactically or psychologically to the challenges posed by Finland’s formidable environment. The cold sapped their morale, enervating and maiming their bodies; the terrain stymied their conventional strategy.

For the Finnish, of course, dealing with such things was already second nature. They knew to dress in layers to keep out the cold. To eat heartily. To carry morphine in the warmth of their mouths or armpits. To lubricate their rifles with both gasoline and gun oil rather than conventional petroleum. To run their trucks for fifteen minutes every two hours. And of course, they knew how to orient and ski over whited out landscapes of unending snow and ice.

The Finns were not only adapted to the harshness of their home environment, but sought to leverage it for their gain — to turn what the enemy saw as liabilities into assets.

As we’ll see, Finnish troops allowed the geography of the battlefield to dictate their strategy, emphasizing speed and surprise over brute force, and utilizing the environment as an ally that could weaken the enemy in ways their limited artillery alone could not.

Compensate for a Lack of Size/Power/Resources With Speed and Agility

The greatest way the Finns turned potential obstacles to their advantage can be seen in terms of their superior speed and mobility.

The Soviets rolled into Finland planning to deploy a conventional battle strategy utilizing large-scale frontal assaults.

There was just one problem with this very linear plan: it was wholly unsuited to the Finnish terrain.

At the time, Finland had few roads. Of those which existed, none were paved, few were interconnected, and almost all were narrow. Once a column of troops and vehicles headed down these pinched pathways, movement options were limited to either continuing forward or retreating back; the thick forests and enormous snowdrifts that flanked the roadways made moving laterally between them by foot or vehicle nearly impossible. Such areas could only be traversed on skis.

This mode of transportation, however, was not a viable option for the Soviet troops. Some units were given skis, but no training on how to use them. Other units were given how-to manuals on ski warfare, but no actual skis.

Finland’s forests thus remained fairly impenetrable to the Russians, who stuck to slowly moving their gargantuan armored convoys down the only available roadways, a position that left them vulnerable to small, crack teams of Finnish ski troopers, who had been gliding through the trackless forests since they had been old enough to walk. The Finns’ adeptness at skiing kept them highly mobile — allowing them to launch rapid ambushes and disperse quickly — and opened up a wide range of possible maneuvers and angles of attack.

The Soviet military’s unimaginative and sluggish leadership, was not only literally road-bound, but metaphorically hidebound as well. They employed the same full-bore tactics again and again, regardless of what the particular situation called for, and how many needless casualties the strategy incurred.

In contrast, the Finns’ literal go-anywhere agility was accompanied by a do-anything mindset; freedom of movement went hand-in-hand with freedom of thinking. Unit and individual initiative and innovation were prized as ways to compensate for numerical and technological inferiority, and officers hatched experimental ideas in collaboration with their men.

Divide and Conquer

While their mastery of skiing enabled Finns to launch quick, agile attacks on the long, winding columns of Soviet troops and supplies, these armored convoys were still a force to be reckoned with.

The Finns thus enhanced the efficacy of their efforts by literally breaking the columns into “bite-sized” pieces that could each be dealt with more easily as smaller units.

Finnish soldiers would separate the Russian convoys by blocking the road with felled trees. They would then encircle each isolated pocket — what they called mottis after a measure of chopped and stacked firewood — with their own command posts, supply depots, and camouflaged dugouts. Once the enemy was thus entrapped, the Finns harassed and raided the motti around the clock, continually emerging from the dense forest to inflict casualties, destroy supplies, and wear down the Soviets’ morale. If a motti, even in its fragmented state, still remained too strong to attack directly, the Finns weakened it through attrition, cutting off food and supplies until the target was “soft” enough to be eliminated.

Utilizing “motti tactics” allowed a much smaller force to hold its own against a far larger foe, and sometimes resulted in astonishingly one-sided victories for the Finns; in the Battle of Suomussalmi, for example, employing the technique helped the Finnish forces kill 27,000 Russians, while only losing 750 of their own men.

Utilize Economy of Force

The Soviets could afford to waste men and ammunition with near reckless abandon; their enormous population size and flush stockpiles of supplies ensured a steady stream of replacements for men and material.

Finland’s far smaller population and manufacturing capacity, however, meant that their reserves of resources were stretched thin from the very start.

This lack dictated the economical deployment of the resources they did possess; energy and material were carefully rationed and judiciously expended in ways designed to maximize their ROI.

Such economy of force rested centrally on marksmanship. Conserving ammunition meant that every shot had to count; bullets and shells could not be fired haphazardly, but had to be saved for the most opportune targets and hit their marks as often as possible.

This meant selecting artillery best suited to the terrain and placing batteries in places and at angles where they were thought to be most effective — calculations that required mapping and adjusting their positions to the inch.

It also meant striving for near perfect precision and accuracy in shooting, and in this the Finns assuredly excelled. Their antiaircraft brought down hundreds of Soviet planes – a number made more remarkable by how few times these guns were fired; Winter War historian William Trotter estimates Finnish antiaircraft garnered “one kill for every 54 rounds of cannon fire and one low-altitude kill for every 300 rounds of automatic fire” — highly effective shooting.

On the ground, the infantry’s ranks were filled with similar sharpshooters — men who had grown up hunting — who had “tracked bear and wolves over this same ground and who could drill a man through the head at 1,000 meters with their first shot.”

The employment of snipers — assassins who could take a man down with only a single bullet — thus unsurprising played an outsized role in the Finns’ resistance strategy. Concealing themselves in trees, they “waited patiently, sometimes hours, for an officer to come into their cross hairs.”

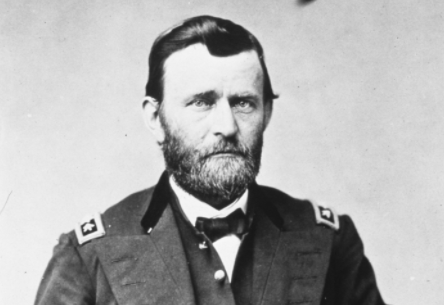

The most prolific of the Finnish snipers, Simo Häyhä, is reported to have killed 505 Russians — the highest number of sniper kills in any major war. Called “White Death” by the enemy into whom he continually struck fear, he managed this deadly feat in fewer than 100 days — averaging more than 5 kills a day — in a season in which daylight lasts for only a few hours.

That’s economy of force.

When Resources Are Few, Improvisation Becomes Key

Given the Finns’ acute shortage of every form of ammunition and weaponry, they not only had to ration their firepower, but supplement it by getting creative.

Trotter details some of the ingenious improvised booby traps the Finns left behind in abandoned villages, as well as the other jerry-rigged implements they devised for resisting the enemy:

“Everything that moved seemed attached to a detonator; mines were left in haystacks, under outhouse seats, attached to cupboard doors and kitchen utensils, underneath dead chickens and abandoned sleds. The village wells were poisoned, or, if time and chemicals were lacking, fouled with horse manure. Liberal use was made of cheap pipe mines—steel tubes crammed with explosives, buried in snowdrifts and set off by trip wires; the charge went off at waist level and caused very nasty wounds. A colonel named Saloranta invented a type of wooden mine, impossible to detect with electronic devices, that was powerful enough to blow the treads off a tank. Soon the Russians had to detach patrols to clear the roads with sharp prods before the tanks could advance. Under the newly frozen lakes, mines were strung on pull ropes; only partly filled with explosives so they would retain buoyancy for several days, the charges were not designed to blow up the tanks but rather to shatter the ice beneath them. When word got around about this tactic, the Russian tank drivers began to avoid the lakes altogether, which was precisely what the Finns wanted, since it was much easier to ambush the vehicles in the countryside than out on the lakes, where their guns could sweep the terrain all around. At several locations the Finns unrolled enormous sheets of cellophane over frozen lakes so that, from the air, they would look unfrozen, and the enemy would not even bother trying to cross them.”

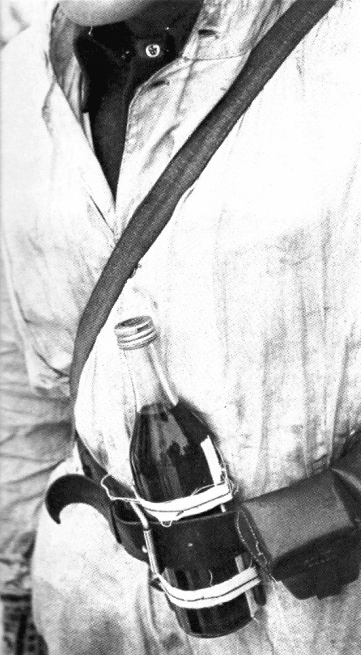

The improvised weapon the Finns were most famous for employing, however, was the Molotov cocktail. While they didn’t invent this flaming projectile, they did refine its effectiveness and lend it its enduring name.

Finnish guerillas transformed the incendiary devices from the mere gasoline-filled, small fireball-creating bottles that had originated during the Spanish Civil War into more explosive and damaging weapons. Kerosene, tar, and potassium chlorate were added to the bottles’ contents; wind-proof matches or a vial of chemicals (that would ignite on breakage) were attached to their sides, eliminating the need to pre-ignite wicks stuck directly inside them. The Finns’ Molotov cocktails could pack a real punch, and helped stall dozens of Russian tanks.

Yet part of this improvised weapon’s efficacy may simply have come from the morale-boosting name the Finns christened it with.

When the Soviet Air Force bombed Helsinki on the first day of the war, criticism of the attack poured in from many corners of the globe. In response, Russian premier Vyacheslav Molotov explained that his high-flying comrades had not been dropping bombs, but rather food and humanitarian aid for the starving Finns. The Finnish people, who were neither starving nor amused, thus wryly took to calling the bombs “Molotov’s bread baskets” and the incendiary devices they hurled back at the Russians “Molotov cocktails” — “a drink to go with the food.”

Practice the Art of Silence and Surprise

A key aid in the effectiveness of Finland’s snipers in particular, but all its troops as well, was their adeptness at the arts of concealment and camouflage. Milky white uniforms made them nearly invisible against the snow. Multi-purpose stoves used for warmth and cooking emitted little smoke, and made the location of their camps less obvious. Skis to transport men, and reindeer-pulled sleds to haul heavy equipment, made their movements a mere whisper. Their presence was even harder to detect given the fact they often conducted their raids during the long arctic nights.

This mastery of stealth turned Finnish ski soldiers into deadly phantoms, who silently emerged from the trackless forests to spring unexpected ambushes. The Soviets’ first and only indication of their enemy’s presence was often a spatter of blood and the sight of a comrade falling into the snow. The Finns’ surprise attacks not only worked on a practical level, but on a psychological one as well: having to be always on guard against these invisible ghost-like guerillas deprived the Russians of sleep, made them anxious and jumpy, and sapped their morale.

The Soviets’ khaki green uniforms showed conspicuously against the white snow.

In stark contrast, the Soviet soldiers could not have more glaringly advertised where they were and what they were up to. They entered Finland wearing dark green uniforms and helmets that sharply silhouetted them against the white snow; their olive drab tanks similarly stood out like sore thumbs. It was not until three months into the war that the USSR issued the troops white snowsuits and painted their armored vehicles to match the frosted terrain.

Russian camps similarly announced themselves from afar. The Soviets cooked with big field kitchens whose tall chimneys sent thick smoke signals to the Finnish forces. For warmth, the Russians gathered around huge, roaring campfires, the glowing flames of which not only gave off plumes of telltale smoke, but helpfully delineated the vulnerable figures within a sniper’s cross-hairs.

Success Attracts Aid, Investment, and Assistance

Norwegian volunteers joining the Finnish fight

It’s hard to convince potential partners, investors, and allies to come to your cause when you’re an underdog facing long odds — especially when you’re an unknown entity who doesn’t have any track record of success. It’s once you start making some achievements on your own, that people become interested and want to get involved.

Finland understood this from the outset. While its desire for a Western power to commit full-scale assistance was discussed within several allied governments, action on any such plan didn’t emerge before the Finns were forced to sue for peace in March. But their improbable, tenacious stand and inspiring one-sided victories didn’t go unnoticed. Amidst the so-called “Phony War” in which latent tensions on the continent built, but the Western powers took little action against the aggressions of Germany and the USSR, Finland was one of the few arenas in which a real fight for freedom was already underway. Those who sympathized with the Finns’ cause, and admired their back-to-the-wall, all-out resistance, flocked to the frontlines.

Material aid was sent from many countries, and eight thousand Swedes, eight hundred Norwegians and Danes, a battalion of Hungarians, and a fleet of Italian pilots volunteered to fight alongside Finnish troops. Even Kermit Roosevelt, Teddy’s son, assembled an “international brigade” made up of a motley crew of recruits from all over the world. Alas, a force he dubbed the “Finnish Legion” arrived too late to wade into battle.

Keep at Least Some Aspects of Life Comfortable When Others Are Difficult

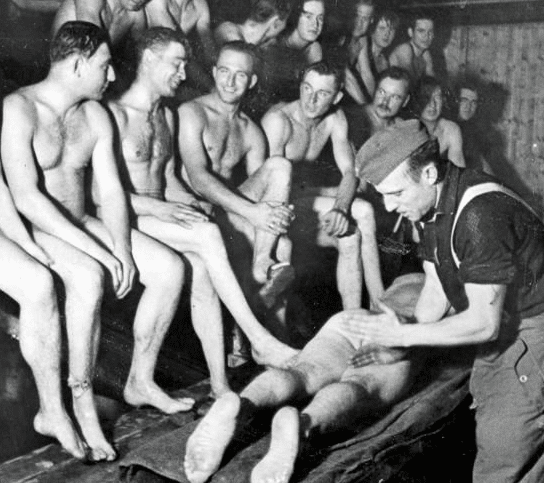

Soldiers taking a break from the frontlines to engage in Finland’s national pastime: sittin’ in the sauna.

Willpower is a limited resource; when you use part of this mental fuel for one task, you have less of it for others. That’s why it’s not recommended that you try to achieve several strenuous goals simultaneously, or even at the same time that other aspects of your life are significantly challenging. For example, it wouldn’t be a great idea to try to go on a strict diet right when your new baby is born, or quit smoking right after your dad dies. When you’re working on a difficult aim, it pays to make other aspects of your life more stable and comfortable, so you can preserve and direct as much of your available willpower towards it as possible.

The Finnish fighting forces intuitively understood this principle. Even though they stoically embraced all the hardships inherent to their homeland, and to the arena of war, they carved out a little comfort, a little rejuvenating respite, whenever and wherever they could.

While the Soviets subsisted on black bread and unsweetened tea, fare insufficient to fuel the body in such frigid temperatures, the Finns regularly dined on hot, hearty food. It’s said an army marches on its belly, and these substantial meals kept the troops physically healthy, mentally resilient, and ready for action.

While the Soviets shivered in substandard uniforms, the Finns, Trotter notes, repelled the spirit-sapping cold by dressing in layers of “heavy woolen underwear, sweaters, several pairs of socks, boots lined with reindeer fur, and a lightweight snow cape.”

While the Soviets ground out their job in freezing, haphazardly constructed trenches, the Finns retired to warm, cozy dugouts that were lined with animal furs and skins, covered with straw and handmade blankets, heated by hot stoves, and covered with camouflaged log roofs. Ski troopers were frequently rotated between active duty on the frontlines and rest behind them, and were thus never too far from these nests of reprieve; as Trotter reports, their “schedule called for two hours’ patrolling, two hours’ rest in a warm dugout, then two more hours of aggressive activity, followed by a four-hour rest period for sleeping and eating. Every two or three days, if the level of fighting permitted, each man would get a turn in one of the frontline saunas, a luxury the Finns could not do without even on a battlefield.”

By maintaining a few baseline creature comforts, the Finns were able to sustain a high level of morale, even as they exerted themselves in the harshest of conditions.

It Ultimately Comes Down to Your Sisu

Morale could in fact be said to be the only resource that the Finns possessed in greater quantities than their enemy. Though they wouldn’t have called it that.

Instead, they called it sisu.

The exact meaning of sisu is hard to describe. There isn’t a single word in English with a literal parallel, and even in Finland the idiom stands in for a cluster of traits. That cluster includes stoic determination, hardihood, grit, bravery, willpower, tenacity, guts, and resilience. Balls, one might say. Sisu is an action-oriented mindset; it is manifested in the decision to grapple with an endeavor with long odds; to take on a challenge seemingly above one’s mental and physical capacities. It is called upon when adversity and opposition push you to give up, and your white-knuckled courage allows you to hold on.

The Finnish people feel that sisu constitutes the heart of their national culture. It was certainly the heart of their resistance during the Winter War.

Sisu is what allowed Finnish soldiers to creep close to Soviet tanks to throw grenades, plant charges, and even attempt to crow bar off their treads. It’s what inspired them to keep volunteering for the job, despite its 70% casualty rate.

Sisu is what inspired Finnish pilots to fly their half-as-fast, two-decades-old biplanes into formations of modern Russian fighters that outnumbered them 20 to 1. It’s what enabled them to overcome such handicaps to shoot down 10X as many of the enemy as they lost themselves.

Sisu is what animated not only the guerilla ski troopers who fought in the forests of Finland’s interior, but those who manned the Mannerheim Line — a line of fortifications that stretched across the Karelian Isthmus. Here the Finns were forced to make a more conventional stand in attempting to halt the advance of Russian troops. Here their daring, speed, and innovative tactics counted for much less, and their sisu for much more.

In February, Stalin grew exasperated with how long the invasion was taking, and threw 460,000 men, over 3,350 artillery pieces, 3,000 tanks, and 1,300 aircraft against the Line, carpet bombing the area and overwhelming the Finns with relentless frontal attacks. The Finns held out against this daily onslaught as the shock waves from the bombardment concussed their comrades’ brains and collapsed their dugouts, burying men alive. They held out as the Soviets overpowered each position in front of the Line, forcing the men into brutal hand-to-hand combat. They held out as their ammunition depleted, and they were left with nothing with which to assail the enemy besides Molotov cocktails and taped-together grenades. They held out for weeks until the disintegration of their defense had become too dire, and the Finnish government was forced to negotiate an end to the war.

The Mannerheim Line was ultimately breached, but the sisu of the Finnish people remained intact.

As Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, Commander-in-Chief of the country’s defense forces, and the man for whom the Line was named, said to his undaunted men upon surrender:

“We have not fled. We were prepared to fight to the last man. We carry our heads high because we have fought with all our might for three and a half months. More than that, one can scarcely demand.”

Conclusion: Got Sisu?

While Finland was forced to give up more land to the Soviets than they had originally asked for, in initially resisting Russian demands, they dodged the fate of those Baltic countries who passively negotiated with Stalin in 1939. Those which agreed to Russian demands for the building of bases and stationing of troops eventually found themselves entirely occupied and incorporated into the Soviet Union outright, significant swaths of their populations deported and sent to labor camps.

The Finns’ gritty, improbable resistance also left a legacy of inspiration, buoying the spirit of freedom at a time when autocracy was on the advance, and offering a case study of what’s possible when a little guy with limited resources takes on a Goliath-like foe. By refusing to buckle to despair; by digging in instead of selling out; by making much out of little, turning obstacles into advantages, thinking outside the box, and playing to their strengths, the Finns harnessed the timeless and perennially surprising power of the guerilla warrior. It’s a power that comes with facing down long odds, and deciding to fight back anyway. It’s a power motivated by grit, by determination — by that incomparable secret sauce: sisu.

For insight into how Finns continue to live with sisu in the modern day, listen to our podcast with Joanna Nylund:

__________________________________

Source:

Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish War of 1939-1940 by William Trotter