You’re probably familiar with the mythological tale of Hercules (or “Heracles” as the hero was originally called) from books, comics, and movies. But while Hercules is often rendered as a kind of one-dimensional superhero in popular culture, my guest today argues that he’s actually quite a complex character, and that the story of how he completed twelve epic labors has a lot to teach us about endurance, revenge, mental illness, violence, punishment, trauma, bereavement, friendship, love, and masculinity.

His name is Laurence Alison, and he’s a forensic psychologist and an expert in interrogation, who’s created a written and oral retelling of the classic myth. At the start of the show, Laurence shares how he’s been using the story of the twelve labors of Hercules to facilitate reflection and discussion amongst military personnel and first responders, and how the labors can provide life insights for everyone. We then dig into the details of many of the labors of Hercules, from slaying a lion to cleaning out stables, and discuss what they can teach us about grappling with life’s highs and lows, and what it means to be a man.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- Our last podcast with Laurence about what he’s learned from his work in interrogation about building rapport

- AoM Podcast #660: The Theater of War With Bryan Doerries

- AoM Series on Greek Mythology

- AoM Manvotional: The Choice of Hercules

Find Laurence Alison’s Hercules Retellings

- The Heracles Project on the Grand Truth website

- Direct access to the oral retelling of the labors of Hercules (this is an audio experience with music, sound effects, illustrations, and guided interpretative diary exercises)

- Print copies of Laurence’s written, illustrated retelling of the labors, as well as a novella Laurence wrote on the entire life of Hercules, are available to purchase by contacting Andrew Richmond. You can get a feel for the former book here.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript!

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Now you’re probably familiar with the mythological tale of Hercules or Heracles, as the hero was originally called from books, comics and movies. But while Hercules is often rendered as a kind of one-dimensional superhero in popular culture, my guest today argues that he’s actually quite a complex character. And the story of how he completed 12 epic labors has a lot to teach us about endurance, revenge, mental illness, violence, punishment, trauma, bereavement, friendship, love, and masculinity.

His name is Laurence Alison, and he’s a forensic psychologist and an expert in interrogation, who’s created a written and oral retelling of the classic myth. At the start of the show, Laurence shares how he’s been using the story of the 12 labors of Hercules to facilitate reflection and discussion amongst military personnel and first responders, and how the labors provide life insights for everyone. We then dig into the details of many of the labors of Hercules, from slaying a lion to cleaning out stables, and discuss what they can teach us about grappling with life’s highs and lows and what it means to be a man. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/hercules.

Alright, Laurence Alison, welcome back to the show.

Lawrence Alison: Thank you so much for having me again, Brett. It’s lovely to be here.

Brett McKay: So we had you and your wife on the show a year ago to talk about how to build rapport, and you two have a unique perspective on this because you are experts in interrogating criminals and terrorists, and you have to build rapport with these guys to get information from them. And that’s episode number 648 for those who wanna check that out. You’ve got a new book out and it’s about the mythical labors of Hercules. Now, this might seem like it’s coming out of left field for a guy who’s an expert in interrogating terrorists, but the book came out in part because you worked in the military world and in the law enforcement world, and you kinda landed on the myth of Hercules as a way to facilitate discussion with military vets and other first responders and help them communicate with each other, correct?

Lawrence Alison: Yeah. Well, I think you had a… I listened to your great podcast that you did with Bryan Doerries and his work on Theater of War. And he was making the point that the Greeks were doing this many years ago, and it was a strategy of telling their young soldiers or a fee boy myths, legends, and stories, and seeing how they interpreted them in a way that they were able to talk about difficult themes, love, loss, bereavement, friendship, vengeance, senior authorities letting them down, political things, post-traumatic stress and so on. And these myths and legends are near enough to the reality of what they’re dealing with, but far enough away to make it a safe learning environment.

So if you look at the story of Hercules, many people think of The Rock or the Disney version or whatever, of him basically being just essentially a strong guy. But the complexity of Hercules as a masculine figure, the more I read into it, the more you can get out of it. And we were finding with some of these guys I was doing work with them when we were reading out a labor and saying, “How do you interpret that?” It was very interesting how each individual saw each labor rather differently, and it was enabling them to talk about topics that otherwise might be a little bit too close to the bone. And as we all know, part of healing is talking, simple as that.

So it was a device to get people talking and actually uncover some things about themselves that perhaps some of which was surprising, but perhaps other bits not. So it’s a complex multi-layered, cognitively chewy tale I think. There’s no surprise that these myths and legends have a really enduring property that is relevant today as they were in the 6th century BC.

Brett McKay: It sounds very like a mythopoetic, sort of a Robert Bly, Iron John. You use a fable or a myth to talk about issues. As you said, it’s useful, what’s useful that it’s detached enough where you’re not, like it’s not too on the nose, but it allows the person to get the conversation going in a different direction.

Lawrence Alison: Exactly, exactly. And some of the sort of beats of the story are much more obvious than others. We know that when Hercules returns from war and he’s battle scarred and traumatized, Hera, who’s always cursed him from birth because she hates the fact that he was born out of Zeus’ infidelity, makes him hallucinate and see his wife, Megara, and his children as demons in the house. And seeing those kids as demons, he attacks them, kills them, and throws them on a fire, and there’s a very obvious direct links to kind of returning war vets finding it very difficult a return to normal life, a sort of madness that they can encounter when they’re undergoing PTSD. And then this sort of redemption story or atonement journey that Hercules goes on thereafter, and that’s what leads to the 12 labors.

Brett McKay: And what’s nice about this book, it’s well-done, it’s the stories. You did a good job making the stories captivating but succinct. But they’re also, they’re wonderfully illustrated, so very evocative. And what I found too as I was reading this, I understood like, “Well, Laurence is using this with vets.” But as I was reading this, I was like, “Well, this is applicable to anybody just going through just mortal existence where things are hard, you’re faced with hard decisions, you’re faced with setbacks.” And each of the labors, I found were eliciting questions or reflections for me who’s not a military veteran.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, absolutely. Well, the weird thing is, I sort of gave it as one always does with one’s parents, they always want a copy of your book, or the thing that you’ve produced, or the podcasts that you produce, and sometimes they listen and sometimes they read, or sometimes they say they’ve read it and they haven’t but they say it’s great. But what was interesting, I gave it to my parents and they said they were reading each of the labors out one per night, and they’re in their 80’s. And they were interpreting them differently and they really did kind of get into them. So you’re right, Brett, it’s got a huge resonance. And actually, I honestly think without being too sort of doing my own therapy on air, it really helps me. There was stuff in it that I was reading and that I’m still contemplating now. I love the ambiguity of it. He really isn’t just simply a heroic figure. What is he? A berserk or a madman. Has he got mental health issues? He’s a murderer, he’s a rapist, he’s a very, very complex nuanced figure. And the journey that you go on in the reading of it or the listening to it will reveal as much about you probably as it will about him.

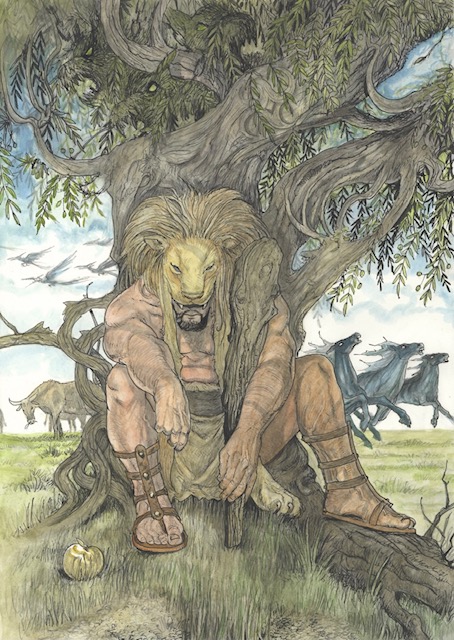

And you’re right as well, I’ve gotta give a shoutout to David Hitchcock for the illustrations. And the weird thing is actually, when I got in touch with David, he’s a wonderful illustrator in the same kind of vein as Sydney Paget that drew the Holmes stories and Tenniel that drew Alice in Wonderland, he really is that old school wonderful sort of illustrator. And bizarrely, neither he nor I could find a set of 12 illustrations of all 12 labors, which I just found weird that it’s been around for so long. So it was fantastic working with David and some of the writing and storytelling, I did around what he’d actually produced as an image. But yeah, going back to your question, Brett, there’s lots in it for everyone, it could be as applicable or relevant to children as I think it could be to people that have retired, it’s not the exclusive domain of vets or law enforcement by any means.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s dig into the story and the takeaways from it. And as you said I think most people, they’re probably familiar with the Disney Hercules version, which as my 10-year-old son, when we watched it this year, he’s like, “That’s not how the story went.” He understood. He understood the Hera dynamic and that doesn’t show up at all in the Disney version. So let’s start before the labors of Hercules, ’cause that’s, I think, that’s the back story that lays the groundwork. What’s the back story of that? And then how did… I mean, it’s a lot of stuff. It started off with Hercule’s parents. How did those decisions influence the Labors of Hercules?

Lawrence Alison: Well, I start off with a chapter called The Boy that Strangled Snakes. So anyone that’s familiar with the story, will know that Zeus… The amazing thing about the Greek gods is they’re all capricious libidinous kind of complex figures and Zeus, god of the gods is going around spreading his seed all over the place. And basically he appears in the form of Alcmene’s husband and essentially rapes Alcmene. So they have a child whose part mortal, part god, and Hera who is Zeus’ wife hence Heracles or that’s where the name Heracles comes from, got changed in the Roman to Hercules. But Hera has this lifelong relationship with Heracles because she curses him from birth. In fact she tries to prevent his birth. There’s a couple of things that she does, but a notable feature is that she puts two snakes in his cot to try and kill him.

And a defining moment in Heracles’ life is Alcmene runs into the room to see Heracles in his cot with the two snakes in his hand, having strangled them and kind of laughing. So it’s at that point we realize that we’re dealing with an unusual child that in the face of death and uncertainty and risk and peril grabs these two things, kills them and endures.

So a common trope in Greek mythology is bad parenting or abandoned parenting or infidelity, and the child nearly always pays for the sins of the father and Hera curses him throughout his life, as I said before, the madness when he returns home and various other labors that he goes through. But that’s where the story starts, through Zeus’ infidelity, we get this interesting character that doesn’t quite sit with the gods, doesn’t quite sit with the mortals, and in a way, he casts a somewhat lonely figure. Although as I say, as a child he’s a sort of happy, enduring, robust, young man that is able to deal with adversity even as an infant.

Brett McKay: And look, like you said there’s takeaways from that applicable just to anybody. The idea is our parents have a big influence on our lives and their mistakes can influence us the rest of our life, even if they’re not proactively trying to curse us, their decisions can have consequences on our lives for good and for bad. So he does these 12 labors, why does Hercules have to do these 12 labors or feats? What’s… Why that?

Lawrence Alison: Well, depending on what source you go to, sometimes the murder of his wife and children bizarrely comes after the labors, but in other versions of the story, it comes after them. But I saw it as his effort to… Well, actually interestingly, when we get to the labors, different people will read different things into it, but certainly I saw it as his form of atonement or seeking redemption after he’d murdered his family. He has this hallucination murders his family goes to the temple of Apollo, god of truth and prophecy, and seeks atonement, and is told by the priestess at the temple to seek out King Eurystheus and complete these labors. And it’s an endurance test for him. It’s can he do them? But different people will see his motivation for doing them as rather differently. So if we take the first labor, the Nemean lion, in very, very simple terms, the first labor that King Eurystheus sets Heracles is to go and kill the Nemean lion, which has been terrorizing people in Nemea, and he chooses to go without weapons. He defeats the lion, he skins the lion, and we’ve all seen in The Rock’s version of Hercules, he has the lion hide as a kind of armor afterwards.

And it’s quite interesting, when I did the first version of this story with some paramedics and military personnel, one of the prompts at the end of that labor is, “Okay, so why did Hercules go without weapons to this fight?” And I got two really different answers straight away. One of the paramedics said, “Well, I think he’s on a suicide mission, he’s gone there to basically kill himself and that’s his motivation. He’s got no intention of completing the last few labors and actually, maybe he sees it as fate that he’s able to defeat it.” I spoke to one of the military guys and his view was, “No, no, he’s gone without weapons ’cause he wants to test himself. He wants to test himself as a man without help, without weapons, with nothing but his bare hands and it’s a test of his robustness and rigorousness.” So straight away, you start seeing these different pathways or different interpretations of the same story.

Brett McKay: And then I guess it just depends on your background. So okay, well, the other prompt too, like, what do you make of this? What are the answers you’ve got when you’ve asked that question? Okay, so he kills the lion, skins it, and then he puts the skin on and he wears it for the rest of his labors that he does. When you asked them like, “What’s going on there?” What are some of the responses you get?

Lawrence Alison: Well, again, variable, but I guess the two main ones that you tend to get is either people will say, “Well, it’s a symbol of his first labor to remind himself that he was successful, that he’s never gonna forget what he did to the lion and that it was out of respect for the lion that he’s not gonna just let the carcass rot in the sun.” And then other people will say, “Well, no, it’s a much more practical, functional thing that we know that the lion’s hide can’t be pierced, it can’t be stabbed. And it’s his armor. He sees it as the best kind of armor.” So those are the two sort of main responses you get. But again, variable, variable. And actually he doesn’t necessarily wear them in all the labors, just some of them. Certainly when he gets to the dog of the underworld Cerberus, he’s got it back on again because he’s got a three-headed dog trying to rip his arms and fists and forearms off so yeah.

Brett McKay: Well, here’s a question maybe we should ask before we start to get into the labours. At this point does Hercules know that he is the son of gods?

Lawrence Alison: Yes, he knows. He knows about his lineage to some extent. Again I write in the story, at the age of 15, he can lift a cow above his head. So he knows there’s something unique and unusual about him. But again, if you look at the various different sources, Euripides and the various other sort of early versions of the legend, that they will write him differently. Some will make him much more consciously aware of his lineage and others not. So again, it’s very variable. What I was conscious of doing when I was writing this was not feeding the reader too much of what I thought about it. I deliberately, I’m glad you said that it’s succinct, they’re quite short and punchy each of the labours. And I think it’s for the reader to bring some of themselves and their interpretation to each of the labors and indeed to their understanding of the central person in the story. So yeah, that was one of my objectives to leave it sufficiently open.

Brett McKay: The second labour is to go kill a Hydra. And what’s interesting about this one, in the first one, he does it by himself, no weapons. This one, he brings along his nephew. What do you think is going on there? When you ask people like, “Why is Hercule’s nephew there?” What kinda answers do you get?

Lawrence Alison: Well, again, if you look at the first four labours, you’ve got the Nemean Lion, the Lernaean Hydra, the Erymanthian Boar and the Ceryneian Hind. They’re all with beasts and they get increasingly sort of complex. The Nemean Lion is everything stripped back. It’s just Hercules and the Lion. Then we get Iolaus, his nephew, with the Hydra. And most people will know that you chop a Hydra head off and two grow in its place and its… Iolaus is his young nephew and terrified of the Hydra, but steps forward and provides the solution, cauterizes the stumps so that they don’t grow back. Then you get the Erymanthian Boar, where you’ve got these three centaurs that are involved in it, and then the Ceryneian Hind you get a god involved in it. And I see it, again, I don’t wanna give too much away about what I think because again, I think the readers need to see how they see it.

In those first four labors, you’re getting increasing complexity. If you imagine Hercules is at the center of our story, then we start seeing some involvement from his family. A young man that is with him, that’s helping. Then we see some community sort of related people that give him some local knowledge to help solve the riddle of the Erymanthian Boar. And then we see Artemis and when you give this to various different people, military, law enforcement or not, they will often talk about family, when they’re talking about Iolaus and looking after the young people. Then when we get to the Erymanthian Boar, they are talking about helping local communities and local community knowledge and being an intruder in an area that you’re not familiar with.

Then we when we get to the Ceryneian Hind, they’re talking about their bosses, senior people that are assisting them or not, or getting in their way of their job. So there’s a kind of increasing concentric circle of people that you’re involved within. That’s how I see it in the first four labors, and that tends to be what comes out. Hercules starts to look after Iolaus. But again, the idea no man is an island. But this comes back to bite our hero, of course later when King Eurystheus says, “Well actually you need to do two more labours,” ’cause originally, there were only ten. He says, “Because you’ve been given too much help.” So it’s the age old idea that if you were writing about a heroic figure, you have to really beat them up psychologically and really give them a hard time, so that you can see that they’re enduring.

Brett McKay: Yeah, for me, so this is my response when I read the Hydra one. I was like, “Well, this is Hercules being a mentor. He’s showing his nephew how to be a man.” But what’s interesting though, is that his nephew actually taught Hercules something in the process as well. And I’ve noticed that happens in a really good mentor-mentee relationship. It’s symbiotic. It goes both ways. The mentor passes on knowledge, information to the person they’re mentoring. But then the mentee can also teach the mentor things that they otherwise wouldn’t have known.

Lawrence Alison: Well, that’s interesting. So if I was doing the labors on you Brett, I might unpack that a bit more. I might say, “Well, it seems to me that that may be something that is important to you, that you are wise enough to know that your age doesn’t preclude you from learning from the young.” Obviously, you mentioned earlier your son, his slightly more nuanced view of the Disney story not being right. So I get the sense that you’re the sort of father that’s happy to learn from their kids, which is great. Would that be fair to say without sort of now interrogating you, Brett, like we did a bit last time? [chuckle]

Brett McKay: Right. Yeah, you interrogated me last time. No, I would say that’s right. I’m always… I love when my kids have these insights and you’re like, “Wow, that’s wise and beyond your years” I’m always surprised. It’s like a pleasant surprise when that happens.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, and as a father, you wanna be receptive to that because we all get older, we’re all of our time aren’t we? And our kids are growing up and seeing different things and realizing different things and learning things that we have not yet learned because they are closer to them.

Brett McKay: You mentioned that one of the other beasts he had to capture was a Hind. What is that, basically a deer… A big giant deer?

Lawrence Alison: Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Brett McKay: Which doesn’t seem like that’s… What’s hard about that? You just went hunting. But what made it difficult? What made it a labour?

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, Eurystheus who is kind of doughy, pasty, awful cowardly king that’s kind of setting these labours hoping that each one will kill him. He gives him the Lion, hoping he gets torn apart, he gives him the Hydra hoping he would get killed by the blood of the Hydra and then the Erymanthian Boar, he doesn’t think he’s gonna be able to capture that. Suddenly he realizes, “Well, look, this guy is mega strong. This guy’s… He can catch anything, he’s brutally strong. Maybe he’s gonna screw up if we ask him to catch something which is delicate and dainty.” And he is hoping that he’s gonna catch the Ceryneian Hind, but bring it back harmed, that he’s gonna grab it and grab a leg and break it and so on. And in doing so, annoying Artemis, who’s Hind it is, they’ve got the Goddess of the Hunt. That labor changes it a bit, it’s fast, it’s speedy, and it’s delicate. And Eurystheus is hoping that he’s gonna accidentally kill it, so that’s the significance of giving him that labor. Things start to change, it’s… We can’t just keep giving Heracles the same task of essentially beating up some other tough creature, they begin to change, the labors change. That’s the challenge of the Ceryneian Hind, how do we catch this thing who, its legs are so delicate, if we grab it too hard, it’s gonna crush it, kill it, break it and annoy the goddess.

Brett McKay: Yeah, he couldn’t just rely on brute strength, he had to use a little cunning. Before we go on to the next one, let’s stick with the animal, the Beast one. The Boar is interesting ’cause you say he gets some help from some Sinotaurs, and one of them, one of these Sinotaurs is an old friend of Hercules. That’s actually in the Disney movie, there’s the Danny DeVito character.

Lawrence Alison: Right, right, right.

Brett McKay: But what’s interesting there. There’s this weird dynamic where there’s some other Sinotaurs there that were helping him, and one of the Sinotaurs basically has to give up his immortality to help Hercules complete the labor.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, I took some liberties with the story. There’s three Centaurs involved in this. There’s Pholus, who’s Hercules friend, there’s Chiron, who’s a kind of sophisticated Centaur that smells the meat and the wine that they’re drinking, and Nessus who’s this rather scruffy, scrappy sadistic, unpleasant Centaur. The three of… He’s basically saying, “How do I catch this Boar, it’s too fast.” And Chiron, being very wise, tells him, “Well look, it’s a four-legged animal. Chase it up the mountain where the snow’s thicker and it’s belly will get stuck in the snow.” And in telling this story, they’re all sort of getting drunk and drink too much wine, and I can’t remember who it is in the story, but one of them knocks over the quiver of arrows that were dipped in the Hydra’s blood, which we know is toxic, and an arrow happens to fall in par Chiron’s poof.

Lawrence Alison: And because Chiron is immortal, he’s gonna die… He’s not gonna die, he’s gonna be in perpetual pain. He begs to be killed, he begs to the Gods to kill him. And of course Hera, being the sadistic, awful goddess that she is, basically says to Chiron, “There’s only one person that I will allow to take your life, and that must be Hercules.” Now Hercules has to kill the Centaur that has advised him and helped him. It can’t be Nessus, this horrible, revolting Centaur, it has to be the person that’s helped him. And again, depending on your interpretation of the story that that moves us forward. What does that do to Hercules? How does that affect him? What are his responsibilities now? His actions are gonna have consequences for people that are around him. Yeah, things change again there. But… Yeah, how did you see that Brett, and what were your sort of interpretations of that one?

Brett McKay: To me, I didn’t really focus on the fact that Hercules had to kill… It was more, Hercules had, in a way, kind of had to abandon him. And that’s happened. You have people who help you, but then, I don’t know, for whatever reason they can’t go on with you. And in order for you to keep going, you have to leave them behind. And there’s a lot of guilt and conflict about that. We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. After he fights these mythical beasts, the next one, it’s the Stables.

Lawrence Alison: Yes, yeah, the Augean Stables.

Brett McKay: The Augean Stables, and you point out in the book that for the Greeks, when they read this, they would say, this is the turning point for Hercules, or a turning point. Just to refresh, what’s going on in this labor and how is it different from the previous ones?

Lawrence Alison: Okay, this one has no beast at all. King Eurystheus says, “Right, okay, there’s these stables that are run by a guy called King Augeus. It’s had 30 years of manure in these stables, and you’re gonna go and clean that up, and you’re gonna do it in 24 hours.” To my mind, again, people interpret in different ways, but this is really about humiliating and degrading him. This isn’t a feat of strength, this is to degrade him and to have him sort of wallowing in this awful sort of fecal matter. And to sort of add insult to injury, King Augeus is a bit like Eurystheus in that he’s higher up the hillside, he’s very well-to-do, and he won’t even sell the dung to the farmers that are beneath him that might benefit from some of this manure. He’s kind of been storing this manure up for 30 years. Hercules turns up and he says, “Yeah, good luck with that, trying to clean that up in 24 hours, go for it.” And this one is interesting because it shows that Hercules is not simply a strong man. He’s thought about this, and he says to the soldier who offers him the spade to start clearing it out, he says,” No, I don’t need the spade.”

And the soldier looks at him and thinks, “Oh wow, this guy has given up already.” But Hercules hasn’t given up. He starts to walk up the hill, and he goes to an area where two streams meet, and he sees these massive boulders that are holding back the streams, the rivers, from the stables. And with his strength, he pushes those boulders apart. The river re-diverts and sluices out the whole of the stables. And in so doing, not only does it clean the stables, it actually generates manure for the farmers below. And the Greeks saw this as a turning point because of two things: One, it showed that Hercules wasn’t just a strong man. He was a thinker. He could think laterally.

This was a cognitive, really neat bit of lateral thinking. And secondly, it is solving two problems at once: Cleaning the stables, but in so doing, providing manure for the communities below. And certainly there is some suggestion that the Greeks saw this as a turning point because, up until that point, maybe there was a sense of, “Well, okay, this guy has killed his wife and children, maybe we want these labors to kill him off. He’s a murderer, he’s a berserker, he’s lost his mind, he’s traumatized, he shouldn’t be around any longer. Oh, hang on a minute. No, he’s thought about other people.” He has, going back to the Chiron thing and the Nessus thing, maybe he’s learned that his actions have a consequence. And he’s the every day man. In fact, when plays were…

We’re done of Hercules. There’s some suggestion that a lot of the guys that would play him wouldn’t necessarily be your regular thespian actor, they were boxers. They were sort of more brutish, common men that had a connection to the working classes and were seen as put upon. It’s a real turning point because he’s using his brain, his lateral thinking, and he’s thinking of others. That’s at least how I see it.

Brett McKay: One thing that I saw as I was reading that, going back to that… The labor was designed to humiliate him and he went off, was this conquering hero… And that happens to everybody in their life at some point. They have a period in their life where have a lot of success, and it’s like, “I did that on my own.” But then something happens and you lose your job. And you’re forced to metaphorically clean up manure. You don’t wanna do it, but you know you have to do it. And Hercules, he… It wasn’t beneath him, but he decided, “Well, if I have to do this, I’m gonna make the best of it.” That’s the takeaway I got from it. It was like, he’s going into a valley. He went from being this amazing, strong guy to just going into this valley, but he made the best of it.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, you’re right. It’s a perfectly legitimate way to see it. We all have times where we’re low, don’t we? Did you see it as this point where he’s rising a bit or… You sort of seem to be intimating that he was… He accepted the fact he’s gonna kinda have to do this.

Brett McKay: Yeah. He’s capable of doing great things, but now he has to do this really just sort of donkey job that no one wants to do, but he does it anyway. It’s not beneath him.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah I guess what you’re saying is, “Well I’m not going out there to go and defeat a beast. I’m happy to do this job, I can suck that up, yeah.” But he’s inventive in dealing with it. I get what you’re saying. Yeah, 100%. I agree, I agree.

Brett McKay: I can imagine this happening with veterans too. One thing you hear veterans talk about is when they’re in a war zone, they feel competent and they feel like this is what I made to do, I’m excellent at this. So they’re like Hercules fighting the beast, and then they come back to civilian life, which is a lot more mundane, a lot more boring, and a lot of them struggle with that. And they have to use that lateral thinking.

Lawrence Alison: That’s interesting, yeah. I’ve never thought of it that way, but I agree. That makes sense. The coming back is what they struggle with more than the combat bit often. You’ll hear stories, I’m sure you’ve heard them many times, Brett, before, where these vets are walking around a supermarket and it’s like, this is just surreal. But that’s the mundane nature of it and that ability to be creative, I guess, and adapt is gonna help in that regard, I agree. That’s an interesting view point for sure.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Okay the next labour, he has to fight a bunch of birds. But we’re not gonna talk about… That one didn’t really call to me for some… Whatever reason. I’m not sure why. Let’s move right to the Cretan Bull which… That calls to me for some reason. Tell us about the Cretan Bull, what was going on? Was this just another animal just causing havoc?

Lawrence Alison: If we sort of talk about the Lion as being maybe a suicide mission, this is crazy, why the hell is he doing it? And then he starts to triumph and Eurystheus tries to humiliate him with the Augean Stables and okay, now we’re starting to win. Our hero seems to be doing pretty well now, and he’s pretty ballsy in this one because he just goes up to King Minos, there’s this rampaging bull that’s destroying everything, and he just takes it head on. It literally is grab the bull by the horns. He knows he hasn’t got arms big enough to grab it around the neck so… It’s a pretty simple labour this, straight in there, wham, grabs the bull by the horns, leverages it to the ground by using his body weight on one side, ties it up and brings it back to Eurystheus.

It’s pretty simple. And what is interesting to me about this, ’cause I do a load of stuff on [0:30:07.7] ____ and decision-making, the warning sign here for me for Hercules is this is starting to maybe feel a bit too comfortable and confident. And as we all know, once you start having that, I wouldn’t say hubristic sense of self-worth, danger’s on the horizon. In fact, in the bird story, we get some hints that Hera is whispering to Eurystheus saying, “Let him have a few, let him win a few. And it’ll be all the more delightful when we crush him.” The bull one is literally taking it straight by the horns and getting on with the job and bringing it back to Eurystheus, and then things start to change slightly after that. Yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah, after that he has to go corral some mares of Diomedes.

Lawrence Alison: Yes, the flesh-eating mares of Diomedes.

Brett McKay: And he brings along a friend too.

Lawrence Alison: He does, yeah. Again, we’re sort of harking back to the centaur story in that he brings this younger soldier with him, a guy called Abderus who’s a farrier and an hostler, deals with horses and… Eurystheus asks him to go and get these horses from this pretty awful, sadistic character called Diomedes, and I took some liberties with Diomedes. I made him a kind of very sadistic, aquiline type of character who was treating his horses badly so that… So badly that they hate humans and the only thing that they are satiated by or calmed by is eating the flesh of human beings. Again, Hercules being Hercules goes straight up to Diomedes and says, “Look, I want your horses and I’ll fight you for them. And if I win, if you fall to the floor first, I’m gonna have them. But if you win, you can have my boat, you can have my Nemean lion, you can have my Hydra, you can have all this stuff.” They agreed to fight, and of course Diomedes being much more slippery, insidious, deceptive and not as forthright and overt as Hercules… Without giving too much of the game away, something goes really badly wrong where we lose Abderus, which again, how responsible is Hercules for this inability to see this deception that Diomedes has pulled on Hercules. He still triumphs in that he gets the horses, but there’s significant loss.

Brett McKay: Yeah, he loses a friend in the process.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah and has to… Not only does he lose him, but he has to leave him behind.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and that probably resonates with vets. There’s that whole, “Leave no man behind.” Even if they’re dead, you’re gonna bring that body back. That’s been around since ancient Greece.

Lawrence Alison: Absolutely, yeah. The body has always been an important thing to retrieve. Two things that we have here, complete mission, which is… Big [0:32:52.5] ____ soldiers as we know. A really important value system for soldiers is complete the mission coinciding with huge other sacred value, two sacred values colliding near: Leave no man, behind complete mission. And when those sacred values collide and you can’t have them both, you’re gonna suffer loss. There’s gonna be trauma. It’s gonna be tough.

Brett McKay: Does this labor elicit in a lot of conversation from the vets you talk to?

Lawrence Alison: Yeah. It starts to get heavier then, as you can imagine. With the Cretan Bull, we’re seeing triumph, we’re seeing perseverance, we’re seeing rising, we’re seeing efficacy. And now we’re seeing, “God, we didn’t see this coming, this is… Why didn’t I see this? Why didn’t I think outside the box? Why didn’t I think a bit more laterally? Why didn’t I consider that people have more sinister motivations? And just because I am forthright and direct and wear my heart on my sleeve, doesn’t mean that I should imagine everyone else is. I need to start thinking a bit wider than my own small orbit of operating, because again, this isn’t just about me, it’s gonna affect the people around me.”

Brett McKay: Another labor after that, this one is interesting, because it requires more cunning, and it’s kind of weird, he’s supposed to get these apples. And in order to get them, he has to talk to Atlas, the guy who’s holding up the Earth. What’s going on there? What’s the connection between the apples and Atlas? And then, what did Hercules have to do to get the apples?

Lawrence Alison: Well, Eurystheus says, “Well, you’re gonna need to do two more labors now.” This is Labor Eleven: The Apples of Hesperides. And he thinks, “Well this is completely impossible, because I know that no mortal can even pick these apples.” Even if Hercules manages to get past Ladon the serpent that never sleeps… In fact, there’s a couple of different ways of telling this story, but I chose this particular way. There’s a serpent that never sleeps that guards the Tree of the Apples, and even if he kills that snake, it’s physically impossible for a mortal to pick the apples. Hercules knowing this, speaks to Atlas, who’s a Titan, and he knows that the Titan can pick the apples. And basically, he uses a bit of deception on Atlas, because he says, “Look, I will hold up the celestial spheres for you, if you can go and pick these apples.” And Atlas, for people aware of that Greek mythology, was cursed to hold the Heavens up after the Battle of the Titans and the Olympians by Zeus, in perpetuity.

Atlas goes, “Well this is a pretty good gig, going to pick three apples, and this guy’s gonna take the weight of the skies off me.” Of course he agrees, goes across to the Hesperides, picks the apples and comes back. And he sort of says, “Well, how are you getting on holding that?” And Hercules says, “Well, it’s pretty tough, really. How did you manage it? How did you not manage to do your shoulders in?” And Atlas says, “Well, you need to use your legs more effectively, you’re not holding it right. Let me show you.” Which of course, then Hercules allows him to take the celestial skies back, bang, off we go. Thanks for apples, tah-dah. See you later. Now we’re seeing, has Hercules learned from the Mares of Diomedes and the Augean stables and with Chiron, Pholus, and Nessus that you need to realize that other people are gonna be deceptive and you need to be a little bit more cunning. Again, this is showing some degree of learning.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And I think there’s a point in every man’s life where you realize you have to have some cunning. And we usually typically think of it as negative. But I think you can… It doesn’t have to be outright lying or being deceptive, but it’s a matter of being strategic with your decision making.

Lawrence Alison: Yes, it’s an interesting one. When I was sort of looking at this, I was thinking, “Well do I like that about Hercules, that he’s actually kind of duped this guy?” But at the same time, has he only duped him because of Atlas’s own hubris narcissism and willingness to sort of dupe him? When you’re dealing with cunning people, maybe you do have to have a degree of cunning yourself. And actually, technically, Hercules never lied to him. He didn’t say he was gonna take the Heavens forever. But I think… How uncomfortable did you feel with this kind of deceptive element Brett? What was your sort of feeling?

Brett McKay: Yeah. I’m always… There’s always something that’s uncomfortable about Stratego, being strategic, ’cause there is an element of… Any type of strategy, there is often an element of deception. Even if you’re not outright lying, you’re not… You’re withholding information that might benefit the other person to know. And I’m sure you see this in interrogation. You’re not gonna lie to somebody, but you might not say everything you know, and you might use that to your advantage, possibly.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, it’s an interesting one. We may have spoken about this last time when we were talking about rapport. Certainly with our interrogators and interviews, we say “You gotta be really direct and honest here. Even if you’re being honest about the things that you will withhold information on.” If you’re interviewing suspects, you’re not gonna give them all of the forensic information that you have, simply because one of your objectives as an interrogator is to test the veracity of their story. If you give absolutely everything, you are allowing someone that might be lying to you to make some circuitous story about to explain the reason why their fingerprint is on the knife. Going back to the interrogation stuff, we always say to interrogators, “Be overt and honest about the fact that there are going to be some things that you withhold.”

And as long as you’re doing that, it doesn’t have that kind of pernicious, insidious kind of deception. You’re nailing your colors to the mast, but but not being played for a fool either. You’re being upfront about the methods that you’re using. But that said, there is something a little bit uncomfortable about this particular labor with Hercules, because there’s something somewhat cunning about it, in a slightly round-about way where he has not quite been honest about how he’s produced it.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and I’m sure we all face decisions like that. Going back to… You’re using this to help first responders, military guys work through decision-making, you’re always gonna be faced with decisions that have ethical quandaries, where there’s competing interest, “Well I gotta complete mission, but along the way, in order for me to do that, I may have to violate this other ethical standard,” and what do you do in that situation?

Lawrence Alison: Well, that’s right. Where it always gets difficult, and I’m working with a colleague on this at the moment here, in relation to our work on decision-making, what we find is where…

The difference between what we call secular and sacred values. So, a sacred value is a non-negotiable value. We were talking earlier about sometimes in the interviews that we’ve conducted with soldiers, what you will find is that really sacred, completely non-negotiable value is, “You do not leave your men behind.” But another sacred value might be, and often is with soldiers, “You must complete the mission.” And the problem is, where you can’t have both of them. What you often end up with is what we call decision inertia or redundant deliberation. Which is constant chewing over the problem to the point where you are chewing over it for so long that you don’t make any decision at all. But that is where decision-making gets really difficult, where you have to give up one of those sacred values. And that is a tough ask.

Brett McKay: Okay, so Hercules finishes this labor. The next one, he has to go to the underworld. Correct?

Lawrence Alison: Yes, he meets Hades and he has to deal with the three-headed dog Cerberus. Yeah.

Brett McKay: And what was the labor there? What was his mission there?

Lawrence Alison: Well, so this takes us full circle. Labor one is killing the lion and now we’re right back to a kind of another beast. He’s told by Eurystheus, bring the dog back. Bring the three-headed dog back that guards the underworld. Get him off Hades, who is the Lord of the Underworld, but bring the dog back alive. So unlike the lion… Well, like the lion, he’s gotta defeat it without weapons. He’s not allowed any weapons. But this time he’s not allowed to kill it. So, I wrote this in a very particular way that hasn’t necessarily been written this way before. So, often what we do with this 12th labor, we will ask the prompt, “How is this different from labor one? What have we learnt? What is Hercules doing that is different with the dog that he didn’t do with the lion?”

Brett McKay: And he can’t kill. That’s the big one. He can’t just kill it.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, so let’s ask you, Brett, “How has Hercules changed? Now, what’s… If you were comparing these two labors together, what do you think he’s learned, how do you think he’s changed?”

Brett McKay: So, he’s… Likely, he’s gained some confidence. He knows what he’s capable of doing. And in the process too, he’s learned that you can’t just rely on brute force. He has to use his mind, he has to use that lateral thinking, sometimes cunning. I think if this was his first labor, getting the dog, I think his approach would have been just brute force. I think he realized that’s not gonna work here. He has that wisdom that I can’t do that here. This isn’t gonna be the best approach.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, well, he certainly can’t kill it. What is interesting to me about this is that he ends up actually stroking the dog. [chuckle] He brings it back through the streets of Tiryns and back to Eurystheus and parades the dog. And I think everyone is… I wrote a short little epilogue about how the people of Tiryns were expecting to be over awed and praise Hercules for bringing the dog back. And it would be some kind of amazing parade. But I see Hercules bringing back this dog that he’s restrained. And quite as… Used his physical strength, but for restraint. And ends up patting the dog and basically giving it a bit of a cuddle. And this is a dog that has been designed to kill, and hate and rip things asunder.

And actually in restraining it, Hercules calms it. And with the lion, I was cautious to give the view that he felt bad about killing it and here he’s been able to restrain the animal without damaging it, without hurting it, without piercing it, without killing it. Parades it through the streets of Tiryns, and both of them, I see as wounded animals. Wounded beasts that have come back. And actually there, walk through the streets of Tiryns, is to warn the local populace that actually this is what wounded people look like that you’ve put on the front line that have come back from difficult tough times. This is not necessarily some major celebration. Look at the state of us. Be ware. Take this as a warning. It’s not some great celebration, it’s not some ticker tape parade. This is what the reality of war looks like. And this is what the reality of being abused or beaten up or going through tough times looks like. Be warned.

Brett McKay: No, yeah, you can definitely get Jungian with this. It’s like the dog is like the shadow. And this is the idea, I guess, in Jung psychology or depth psychology, you get to do shadow work where you confront your shadow and the dark side of you. But in order to… You have to integrate it somehow. You can’t just beat it down. You actually have to do what Hercules did. Restrain it but just being like, wait… What do we call this? Self-Compassion? Maybe? I just came up with that on the fly. So what are your thoughts on that?

Lawrence Alison: Well, we’re walking into provocative territory…

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Lawrence Alison: Here. But I’m sure you get this with your podcast. The name of your podcast Art of Manliness it doesn’t preclude the idea that women would listen to it but for me, a lot of what the Hercules tale is about is about masculinity. It’s about masculinity in all its strength and in all its weaknesses because… Hercule’s worst points is displaying what would conventionally be considered masculine attributes, but the dark side, the violent side, the impulsive side, the reckless side, the inconsiderate side, the joy in inflicting suffering on other people and violence. But there are certain masculine attributes that are very admirable in the character as well. It is a tale about masculinity. And it is a tale about trying to control that side of you that is disproportionately hyper-masculine but bad. But embracing and celebrating those attributes which are masculine and admirable. So for me, that piece with Cerberus is, as you say, the shadow piece of it, is a reflection of himself. Is a dark side of himself. And without going too deep into it, the fact that he’s restrained the dog is… Perhaps that tells us that he’s starting to get a bit more comfortable with certain masculine attributes that he can control and be a bit more guarded around.

Brett McKay: Alright, so he completes the 12 labors what happens to him? So, as you said there’s different versions of what happens to him after the 12 labors. What path did you take for the after… After the 12 labors.

Lawrence Alison: As I say, I was less convinced just narratively. There’s no right or wrong, it’s a story, right? But I found it unconvincing that he would complete the 12 labors and then go on to kill his wife. I thought there was a much more compelling story to tell it the other way, where the labors and then Hades comes from having killed his wife and children, but then of course…

The weird thing is, he completes the labors, and you would think, Okay, maybe he’s really learned from this, but then shortly afterwards he enters an archery competition where his former teacher, Eurytus, who is a bowman that taught Hercules when he was younger, has a competition in which whoever wins the archery competition can have the hand of his daughter Iole and Hercules has always loved this woman from a very early age, so he enters the competition. Now, Eurytus had hoped and thought that the labors would also kill Hercules and that there would be no way that this violent, abusive man that has already killed his entire family would be available to take part in the archery competition, and yet he knows that Hercules is probably a better archer than him.

Anyway long story short, Hercules does indeed enter the competition and does indeed beat Eurytus who then says, Well, actually, I’ve changed it, you can’t have my daughter, his son Iphitus then it gets into an argument with Hercules, and tragically Hercules loses his mind again and ends up killing Eurytus’s son Iphitus by throwing him off the battlements, so once again, we’re kind of back to square one, and for me, when I was researching this and looking at this story, I thought, Oh my God, I can’t believe he’s gone backwards again to this crazy one impulsive fact where he lost his mind, perhaps for understandable reasons, but he has gone back to that dark side of masculinity, he maybe hasn’t learned from this, and he’s become violent again, and now we’re back to square one, and now he gets more punishment, and now Hermes ‘s punishment for him is that he has to serve three years as a slave to a Lydian princess, Omphale.

Brett McKay: I think, take away there, for applying it to our lives, or someone you’re working with, even if you go through some labor, you think you’re done. I’m done, I’ve got this under control. People, they go to therapy and they make some progress like, Hey, my life’s great, then they stop, they stop going to therapy or they stop doing those things they know will keep them in a good place. Man, that can actually bring you back down and you have to start all over again.

Lawrence Alison: Yeah, a moment of madness can set you back, as you say, being a human being is work, it’s work all the time, You’re not off the hook, you’ve gotta be aware of your strengths and weaknesses of it. You’re right Brett, I think this is about. Well, yeah, just ’cause you’ve done these labors doesn’t mean you’ve stopped, you have ongoing work to do and an ongoing responsibility, and yes, you can embrace your masculinity, but be aware of the dark side of it as well.

Brett McKay: Well Laurence this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book?

Lawrence Alison: Well, we have two versions that people can engage with. On our Ground truth website, we actually have a oral reading of the book, and so people can go to the Ground website and click on project Heracles, and they will get an oral reading of all 12 labors, and you can actually take the labors and do some self-reflective analysis, either just on your own or with teams or groups, and as you said Brett, I think it’s got a very general applicability to a whole bunch of people, and also we have two versions of the book, we have a slimmer version, which is an A4 kinda glossy version, which has the psychology workbook which is called the labors of Heracles, which just has the labors, and then I, Because I got so interested in it, I wrote a short novella it’s about 20,000 words, which is called The Life and Death of Heracles, that has the 12 labors plus the things that led up to the labors and the things that emanated after the labors right the way through to the death of Heracles as well.

Brett McKay: Fantastic, well Laurence Alison thanks for your time it’s been a pleasure.

Lawrence Alison: Thank you so much Brett, it’s great to speak to you again.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Lawrence Alison. Today We discussed his new project around the 12 labors of Hercules. You can find more information about accessing both the oral and written version of Laurence’s retellings of the Labors of Hercules by checking out our show notes at AOM.IS/hercules.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you find our podcast archives, where there’s thousands of articles that we’ve written over the years about pretty much anything you think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad free episodes of the a podcast, you could do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com sign up, use code manliness at check out for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS and you can start enjoying ad free episodes of the AOM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you’d take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Stitcher helps alot. If you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member, who you’d think would get something out of it. As always thank you for the continued support until next time it’s Brett McKay reminding anyone who’s listening to AOM podcast to put what you’ve heard into action.