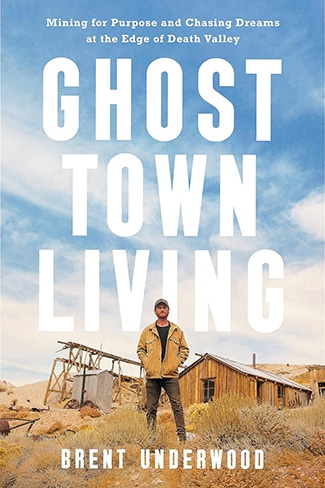

In the 19th century, Cerro Gordo, which sits above Death Valley, was the largest silver mine in America, a place where dreamers came to strike it rich. In the 21st century, Brent Underwood used his life savings to buy what had become an abandoned ghost town, and ended up finding a very different kind of wealth there.

Brent has spent four years living in Cerro Gordo and has documented the details of the mines he’s explored, the artifacts he’s found, and how he’s restoring the town on his popular YouTube channel, Ghost Town Living. Now, in a book by the same name, he takes a wider-view lens on his adventures there and shares the big lessons he’s learned from his experiences and from the original residents of Cerro Gordo. We get into some of those lessons on today’s show. We first talk about how and why Brent bought a ghost town as a way of escaping a typical 9-5 life and finding a deeper longer-term purpose. We then discuss what restoring Cerro Gordo has taught him about the necessity of getting started and taking real action, how learning the context of what you do can add greater meaning to it, the importance of understanding the long-term consequences of short-term thinking, the satisfactions that come with being a high-agency person, and more.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- Burrow Schmidt Tunnel

- Owens Lake

- AoM Article: Become a Self-Starter

- AoM Article: Meditations on the Wisdom of Action

Connect With Brent Underwood

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. In the 19th century, Cerro Gordo, which sits above Death Valley, was the largest silver mine in America, a place where dreamers came to strike it rich. In the 21st century, Brent Underwood used his life savings to buy what had become an abandoned ghost town and ended up finding a very different kind of wealth there. Brent has spent four years living in Cerro Gordo and has documented the details of the mines he’s explored, the artifacts he’s found and how he’s restoring the town on his popular YouTube channel, Ghost Town Living. Now, in a book by the same name, he takes a wider view lens on his adventures there and shares the big lessons he’s learned from his experiences from the original residents of Cerro Gordo.

We get into some of those lessons on today’s show. We first talk about how and why Brent bought a ghost town as a way escaping a typical 9:00 to 5:00 life, and finding a deeper, longer term purpose. We then discuss what restoring Cerro Gordo has taught him about the necessity of getting started and taking real action, how learning the context of what you do can add greater meaning to it, the importance of understanding the long-term consequences of short-term thinking, the satisfactions that come with being a high agency person and more. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/ghosttown. All right, Brent Underwood, welcome to the show.

Brent Underwood: Oh, man, thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: So you are the owner of a ghost town that was once a thriving mining town at the edge of Death Valley. How does a guy like you end up owning an abandoned mining town?

Brent Underwood: Yes, that is a question I seem to ask myself a lot, but I think it was about the right project at the right time for me. I have a background in hospitality and marketing and storytelling and for me, I had just hit that age of 30 where I had a comfortable job, a comfortable apartment, I was living in Austin, Texas, working in mostly digital marketing. I just felt like there was something kind of missing, that there must be more out there, that there was this untapped potential that I wasn’t fulfilling and I just wanted to do something real in the real world. I think that’s kind of the driving force behind it to provide a little more context, but the practical of how you get it, I got a hard money loan, which is basically like as close to a loan shark as you can get these days that fronted a lot of the money, called up some friends to get the rest of the money and bought it in 2018.

Brett McKay: And how did you even know that this was on the market? I mean, that’s kind of weird. You never really see towns, entire towns going on the market. How did you figure this out?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, a buddy of mine was living in Los Angeles and he saw this link that said, “Buy your own town for under a million dollars.” And it was just an amazing headline for an article. And he texted it to me in the middle of the night, and I was living in Austin, Texas at the time and I was running a bed and breakfast basically down there. And he said, “Hey, this might be your next project, lol.” He kind of sent it over as a joke. And for me it was, again, just like it struck me at the right moment and I was just enthralled. It was just everything that I could have ever wanted, I thought. And the more I read about it, I learned about the town, I learned that once upon a time, it was the largest silver mine in California, that there used to be 4,000 residents here and there used to just be like a real life, it felt like a real life western kind of playing out in front of me. And so I just fell in love.

Brett McKay: So when you saw it, when you saw the link, you went to the listing, what did you think you were gonna do with this? Like, I’m gonna buy this thing. What were you hoping to do with it?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, I think, the initial thought was hospitality, some type of overnight accommodation. That was kind of what I had been doing a little bit kind of on the side in Austin. So I thought, hey, this is a beautiful property. To set the context a little bit more, there’s about 400 acres here. There’s about 22 buildings and the town was most prevalent in the 1860s and it’s about three and a half hours outside of Los Angeles, three and a half hours outside of Las Vegas up in the mountains. And so I thought, man, this could be like an amazing place to throw up some cabins, maybe have a little Airbnb, have people could come, they could learn about the history and they could take in the natural beauty all around. So that was the initial plans and that was what, six years ago now? And things have changed a little bit.

Brett McKay: Yeah, we’ll talk about how it’s changed. So the town is Cerro Gordo, that’s the… How do you say the American version? Is it just Cerro Gordo?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, Cerro Gordo is usually how I say it, which is fat hill in Spanish.

Brett McKay: So what’s the story? What’s the story behind Cerro Gordo, what’s its history?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, the town was established in 1860s as a mining town. And originally they were mining Galena here and Galena is a silver and lead ore. And so in around 1865 it was set up as a mining camp. By the 1870s it was the boom town, it was the place you wanted to be if you were in California looking to mine silver, this is just after the gold rush. And so a lot of miners were kind of looking for the next thing and Cerro Gordo was it for a lot of them. And they started mining the Galena originally. And that lasted for about 20 years, probably until the mid 1880s I would say. And then as these mining camps do, the vein was lost. And so a lot of these miners packed it up and left.

The town went from a peak of having almost 4,000 residents down to just maybe a skeleton crew of 20 or so. And then in around 1910, there was a guy that came up named L.D Gordon and he realized that while everybody was paying attention to all of the silver, nobody was paying attention to the zinc. And so he, in 1912, reinvigorated the town as a zinc mining town, and they mined zinc all the way into the 1940s. And so as a mining camp, it had an active life from the 1860s to the 1940s, which is really long. A lot of these camps were set up to be, five, six years was a good timeline for ’em. So as far as like mining towns go, Cerro Gordo had a really long history.

Brett McKay: So, but at its peak it had 4,000 people. That’s a lot of people.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, it’s a lot of people. There’s 4,000 people, a couple hundred buildings up here across the 400 acres. And if you adjust it for inflation, they pull something like $500 million worth of minerals out of here. And at the time the closest port city was Los Angeles. And so a fun fact that I like to think about is when Cerro Gordo had 4,000 residents, Los Angeles only had about 6,500 residents. So they’re almost like equal trading partners more than Los Angeles being the behemoth and Cerro Gordo kind of being something behind it. But like the demand of Cerro Gordo and all the people living here and mining here and doing everything necessitated like a port city to get all their supplies ’cause they weren’t growing much up here. And so I think it’s interesting that Cerro Gordo is one of the reasons that Los Angeles is what it is today. And these days almost everybody knows Los Angeles, but almost nobody knows Cerro Gordo. So I feel kind of like one of my goals up here is changing that a little bit.

Brett McKay: So you pulled together, I think it’s like over a million dollars in a loan to buy this thing, got some friends to help you out and kind of become investment partners on this. What did your family and friends think when you told them, “Hey, I just bought an abandoned mining town.”?

Brent Underwood: I mean, my family is kind of used to it. They, both my parents are teachers and so they kind of wanted me to go into one of those traditional paths and they realized pretty quickly after college that that wasn’t happening. And so they kind of had gotten used to my different adventures. Most of my friends were very supportive too. They knew that I just loved doing stuff like this. And a couple friends were like, “Why don’t you stay with a more traditional path?” I had a very comfortable life in Austin. I had a guy come visit the other day too that was still kind of griping that I should have stuck with kind of what I was doing before. But I don’t know, I think that a lot of them resonated with it and they were pretty supportive.

Brett McKay: Okay. So you bought Cerro Gordo in 2018, but then you waited, it was like two years to actually start doing things, to restore it and kind of bring to life this idea you have of turning it into this place that people can go to, sort of a hospitality place. Why did you wait so long? What was the holdup?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, originally it kind of seemed like one of those projects that maybe you could do as a side business that maybe, hey, I could restore this entire town while still living in Austin, Texas. And we did a lot of things that were just, I mean, I would call them like playing business, which setting up the perfect pitch deck, creating the perfect spreadsheet, wining and dining all these different people that could help with the hospitality, with these different things but it’s really just kind of delaying any real action. And so when the pandemic hit in 2020, March of 2020, my business that was in Austin got shut down because of the pandemic.

And so we were all figuring out where we were gonna socially distance and what better place than an abandoned town in the middle of nowhere. And so I packed it up, came out here and really gave it a shot. I think for the first time it went from a back burner project to kind of the main project and it just consumed me in a lot of ways. And I thought maybe, hey, I was gonna come up here for a week, two weeks, something like that, and it’s now four years later and I’m still here and I no longer have a place in Austin, I no longer have a business here or there. And so it’s just all in at Cerro Gordo at this point.

Brett McKay: All right. So the pandemic kind of helped nudge you along to go all in on this thing. And you talk about this, there’s a former resident of Cerro Gordo who inspired you to sometimes you just gotta get started on something, even if you don’t know exactly where it’s gonna go, it’s this guy named Burro Schmidt. Tell us about Burro Schmidt and what did he teach you about just getting started with something?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, there’s a guy named Burro Schmidt and essentially he grew up in Rhode Island and a few of his siblings had died from tuberculosis. And so doctors, as they did back then, they’re like, you need to really get to a dry climate. And so he moved out here and he was a gold miner and he was prospecting all the time and he basically, every day he’d have to take his ore around this mountain that he was working to get it to town to sell it. And so one day he just decided, I’m not gonna take my ore around this mountain anymore, I’m gonna go straight through it. And so he started chipping away every day with his pickax and a wheelbarrow. And he wanted to burrow a tunnel directly through this mountain. And about 19 years into this process, which is just incredible to think about, like in today’s timelines of which we think about businesses, 19 years into trying to chip through this mountain, they built a road around his mountain.

And so basically his tunnel wasn’t good anymore, it was for nothing. And what I kinda love about the stories is he kept going, he kept going, he got to the other side, he finished burrowing through something like a half a mile of solid granite and then after he was done, he packed it up and left. And I think for me, kind of what that taught me is that the idea, if you, from the outset you were like, hey you need to burrow this tunnel through this mountain by hand, it would just be overwhelming. But I think that like for him, he kind of found his rhythm, he found his thing that like brought him purpose day in and day out and he did it. And I think that one, it was just start somewhere, start something, stop planning, stop, like I said, playing business and setting up different Twitter accounts and just doing all these different things that weren’t actually making a difference and just start doing something.

And then two, I mean, he’s just like a testament to finishing what you started. And I think that again, in today’s day and age, like especially in the job I was working before, it’s very rare I guess is the best way to think about that when I think about somebody like sticking with a project for decades even, I think that today it’s very popular to think about what app can you make to then sell to Instagram and have your exit and like, what is your exit plan going into businesses? But like the idea of sticking with something for nearly 40 years was very, it resonated with me. And I think that like when I got here I was like, if I chip away a little bit, to use an analogy to what he was doing, every day, in 40 years what could Cerro Gordo become? And I think that like pretty quickly after starting, there was more progress that had been done here in the two years that we had just been sitting around waiting for something to happen.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Burro Schmidt, he could have played tunnel maker by coming up with some elaborate blueprint and thinking about all the available technology he had at the time to carve this tunnel out. Instead he just, he became a tunnel maker. I’m just gonna start digging. That’s all he did. I love that. And I just love that he finished it and then he just packed up. He’s like, “All right, did what I wanted to do. I’m moving on.”

Brent Underwood: Yeah, I think it’s cool. I just think that a lot of people look at that and they just dismiss it as, oh, this is a crazy guy that did something crazy. And like there’s that term folly that gets thrown around of like a very impressive feat that had, kind of serves no purpose. But I think that like for the people it resonates with, it resonates deeply. Like, I go to his tunnel occasionally and there’s hundreds of tourists that visit it every week and it’s just something that resonates in today’s day and age. And it’s like a lot of serious people that did a lot more “serious things” beforehand, like nobody’s visiting them or drawing inspiration from what they were able to leave behind. And so I just took away from it that, yeah, I think that like he found his purpose, he found what gave his days rhythm and he just stuck with it, which was really important.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and I think the other thing you learned from him, and I think you picked up on, is that a task of carving a tunnel through a half mile of granite can be so overwhelming that you just don’t do anything. The idea of restoring an abandoned mining town can be so overwhelming that you don’t do anything. Sometimes all you gotta do is you gotta pick up a hammer in your case and just start fixing stuff.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, exactly. And I think that there’s also, once you get into it a little bit, even a couple days, there’s a comfort in that commitment or there’s a comfort in that laying out what’s out there. Like for me, before I would think about what project is next, what project is next, even when you’re in the middle of one project, you’re always thinking about what’s coming next. But like with Burro Schmidt, he didn’t have to think about that. Every day he knew exactly what he was doing. And for me, I feel like now four years in, I feel very relaxed, not thinking about when this project is done, what am I gonna do next to bring some purpose or bring some meaning. Like I hope that Cerro Gordo is the project that I get to work on for the rest of my life. And I think that there’s a lot of like relief in that as well.

Brett McKay: Did you have any construction or restoration background before you started this thing?

Brent Underwood: Not a ton. I had owned a bed and breakfast in Austin, so I did like minor tasks, plumbing this and things like that. But it was more just out of necessity. We’re, the town sits at the end of an eight mile dirt road, so it’s not like I’m running to Home Depot two to three times a day, four or five times a day. Like, there has to be a lot of planning and you just can’t get people up here. And so it was kind of learning as I went kind of.

Brett McKay: Okay. But you didn’t let that deter you, because I think that would deter a lot of people.

Brent Underwood: No, I think that like pretty early on I had realized that it was gonna be a necessity and so you kind of just start figuring out things to do. And I think that I kind of like tapped into one of my original desires to come out here. I wanted to like do real things in the real world. My whole life before that was working on all of these digital projects, which are rewarding in some way, but I think that there is this feeling that probably a lot of people can resonate with of wanting to like build something with your hands, something that you can touch, something that you could work on for the rest of your life. And I think that that desire was being fulfilled here and I figured out the magic of that pretty early on. And I think it was just like a reason to keep going.

Brett McKay: And the other thing that you do great in this book is you share your story, but you also shared these stories of former residents like Burro Schmidt of how the town shaped them or how the landscape shaped them. And a common theme you see through all these people is that they show up here and they really don’t know how to do the thing they want to do and they just figure, I’ll figure it out. As I start taking action and start moving, then I’ll be able to figure it out.

Brent Underwood: Yeah. I think that like a lot of people, Cerro Gordo kind of cast a spell onto people I think. Everybody comes here wanting something a little bit more and everybody comes here seeing the town for having a little bit more than anybody else is seeing. And when they all came here for their different reasons, but they all came here ostensibly to kind of live out a dream or to like have a little bit of a better life. And I think that’s what brought the original prospectors here. They’re walking up the wash looking for float, which is ore that’s left in the wash and they set up shop thinking, “Hey, maybe this mountain can bring things to me that I don’t have in my current life.” And I think that when I showed up here in 2018, I was looking for something as well.

I wasn’t looking for silver in the way maybe they were 150 years ago, but I was definitely looking for a change in my life. I thought that there was that untapped potential both in me and in the property. And then if I were just to stick with it, that the skills would come and it would lead me to the life that I was looking for, at least that’s the hope. And obviously the history book here is full of stories of people being ground into dust by this mountain as well. And so that hope and a dream is what most people come to this town with and a few of them are able to see it through to the other side.

Brett McKay: Yeah, this reminds me of a story from my family on my dad’s side. One of my great-great, whatever, grandpas, was from Switzerland. When he was a young man, he heard all these stories of these pamphlets in Switzerland or newspaper ads about all this great farming land in New Mexico, and if you go out there, they’re just pretty much giving it away and you’ll have this lush verdant farming land. So he is like, “All right, I’m going.” And so he packs up from Switzerland, comes to New Mexico, and then he is like, “Oh my gosh, it’s a freaking desert. Like, I’m not gonna be able to be a farmer.” And so he had to adapt and he became a, he started up a mercantile shop and married a nice Spanish American gal. And my family has roots in New Mexico now.

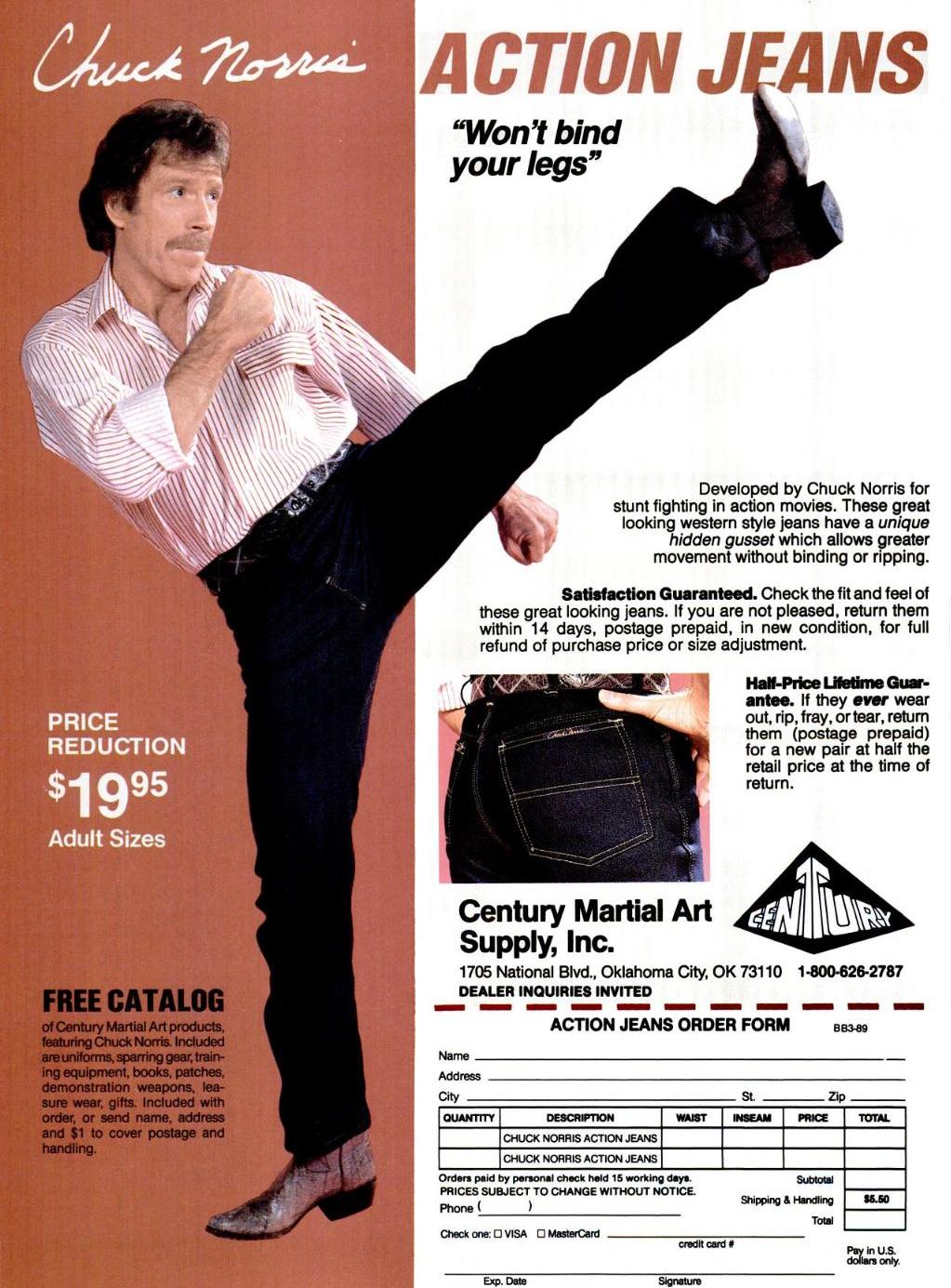

Brent Underwood: Yeah, that’s awesome. I think there’s like, I mean, it reminds me of stories a lot of times when the news of the gold rush hit Europe, a lot of people in Europe would get onto boats, come out west and by the time they got here, the gold rush was done. And so in a similar way they had to figure out what’s next? What am I gonna do? And I think that that adaptability led a lot of them to Cerro Gordo, to be honest, and then to the Comstock Lode after that if they’re thinking about mining specifically. But then a lot became same thing, like merchants like Levi Strauss, Strauss, blue jeans as we know them came out of a merchant who came here and wanted to build better working pants for the miner and now we have all those different brands. So yeah, that western, that allure of the American West is strong. I think it has been bringing people out here for a really long time.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and I think what the desert does too, and you talk about this, the desert is pretty unforgiving and so it forces you to adapt yourself to it.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, nobody’s coming to save you in the desert is kind of what I always think about, and I think that’s another reason, again, that I started developing some of these skills is just that out here there has to be kind of that, a little bit of, not a little bit, there has to be a lot of self-sufficiency ’cause this place can like chew you out and spit you out completely. And then I think once you’re up here you start taking ownerships over situations maybe that you weren’t before and you kind of start developing that sense of purpose and that confidence that hey, I can kind of figure out whatever this place is gonna throw me.

Brett McKay: So you started living in Cerro Gordo, and then while you were there you met your Obi-Wan Kenobi, this mentor who would help you in your quest to restore the town, this guy named Tip. Tell us about this guy.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, Tip is great. Tip is somebody who… I’ve probably made hundreds of videos about my time being up here, and I’ve actually never shown Tip in any of the videos. He wasn’t one that wanted the limelight. His kind of guiding light on all these was pretty pure when I think about it, but he was a guy that had been wandering around these hills for just decades and he knew it like the back of his hand, and I think that in me, he kind of saw somebody to pass along that knowledge. And I was green, I was up here, I didn’t know… Like we talked about already, I didn’t know how to build much, I didn’t know what I was doing, and I felt really fortunate.

I feel like I came up here and with Tip and others, I feel like I was adopted or I adopted just a dozen grandfathers in the first couple of years that I was here, of people just wanting to pass along their knowledge. And Tip was just a mentor in every sense of the word. He would have hated that term, he was not very sentimental, but he was one that wanted to teach me and he kind of showed me that appreciation for figuring things out, for understanding what was around me, for taking ownership over the situation and going forward with it. And I feel that because of him this whole project has been possible. I think it’s, early on in some of these projects, you need somebody like that, and you need to be able to accept somebody like that when they come into your life and Tip kinda changed the whole game for me at Cerro Gordo.

Brett McKay: Yeah. One thing he taught you that helped you learn more about the history of the town and the area is this idea of walking the wash, what is that?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, so the wash is basically… You called it canyon, you could call it basically where the water goes on a mountain when it’s flowing naturally. Like, when the snow melts, where, how does it get to the bottom of the mountain? And I remember one of my early days on here, Tip was like, “Hey, what are you doing tomorrow?” And I said, “I’m not doing much,” lying, even though I had a bunch to do. And he goes, “All right, I’m gonna take you on a hike.” And so we went on a hike, and he brought me into the wash. And basically, his point to me is like we went there looking for different artifacts, ’cause as the snow melts and everything kinda goes into the wash, you can find stuff from the different mining camps that give you a little piece of what life might have been like back in the day here.

And that was kind of his main thing, he was like, “Listen, whenever you need an adventure, just kind of walk the wash. It’s the place of, the path of least resistance, it’s kind of where you’re gonna find a lot of these adventures.” It’s where originally they would have found the ore that led them to the discovery of different mining camps, like Cerro Gordo was in the wash, and I just think that from there, many of my best adventures have sprung, and so it was just like, I don’t know, it kind of accelerated my appreciation for the town a couple of years by him telling me that.

Brett McKay: And something else he was vital in helping you understand were all the mines. So not only is this a ghost town, there’s all these buildings, a hotel, for example, but there’s tons of mine shafts on this thing. And Tip, he knew this stuff like the back of his hand almost.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, he was… So the town’s about 400 acres, like I said, but underneath the town, there’s about 30 miles of mines. And the main mine here goes 900 feet straight down and off of it, there’s branches every 100 feet or so. And so I like to think about it, that there’s almost a city underneath the town here. People come to the town and look around the buildings, that’s where the history is, but none of the buildings would exist unless the things that happened underneath the town happened. And so kind of all the history, all of the origin of this place is under the ground. And when I came up here, Tip was one of the only ones that I’d ever found that actually understood that and had been down there before. And so he kind of sent me on this quest to better understand the mines. I think that whenever you can kind of get that extra context of your setting, whether that’s, if you live in a town and you walk by a park a dozen times, the day that you choose to then look up the history of that park, the next time you walk by that park, it’s going to mean that much more to you.

And Tip showed that to me. He said, “Listen, if you go down to the 86th level, it’s going to come alive. It’s no longer just black and white words on a page, it’s going to suddenly come alive. You’re going to understand the history here. And by understanding the history, you’re going to understand your place within it and it’s just going to become that much more purposeful, that much more meaningful to you.” And Tip very early on has said, “I want you to go and explore. I want you to discover. I want you to live that life of adventure that brought you up here. And by doing so, you’re going to feel so much deeper connection to this town.” And I think that that was a really important lesson to learn early on.

Brett McKay: Yeah. You talk about how learning about the history of the town, it really was fuel to drive your effort to restore the town.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, I just think that context is everything, especially it just brings the world to light, especially your place within it. And again, to use the example of walking by the park, I just think that… For an example, when I… I lived in Manhattan for a while, I was going to school, and I remember pinning up on my wall a map of Manhattan, and every day that I had some free time, I would try to go walk a new street in Manhattan. And I would kind of like highlight in that street when I would get home at night. And I think that for me, it just made my experience much richer. How many times do people just go to work, go home, live in their little bubble, go home, turn on Netflix, and kind of like allow that to be that?

And I think that for me, the history here is very rich, it’s very interesting. It makes me think about the place in a longer term perspective. Instead of just thinking about it as my next project, I think that like, hey, in a 100 years, this decision that I’m making right now is going to impact what people think of this place, what people read about this place. And it’s just like impossible to ignore in a historic place like this. But I think it’s possible to do anywhere. Like I said, in Manhattan, the day I decided to walk every street, suddenly my experience of living in New York was a lot better.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I mean, you can do this in any profession you’re in. So if you’re in, I don’t know, let’s think like insurance, like, learn about the history of insurance in America. I’m sure you’ll be able to find some fascinating characters that’ll give you a deeper appreciation of what you’re doing. Something I try to do with my work with podcasting and writing, I love reading about great broadcasters or great publishers and seeing how they dealt with the issues that they faced when in their profession at varying times in history. And when you look at it, it’s often the same stuff, same problems, they’re just… Things are just slightly different.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, you kind of feel part of a lineage then. You feel like, oh, I’m part of something here. You’re something larger than just yourself. And that’s why I felt like when I dove into the history here, I learned about the different owners over the years from Mortimer Belshaw, that guy who originally created the town. The problems that he ran into with the road, for instance, are similar problems I ran into with the road. Or L.D Gordon, who came up, the guy that discovered zinc, his problems with access in and out of the mine are problems that I still kind of have problems with. And I just feel like once you feel that you’re part of something, and you can, to your point, you’re part of the lineage of broadcasters in a larger sense. And so once you feel part of that, I just think that it enriches your experience day in and day out.

Brett McKay: We’re going to take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show.

So another character you write about in the book that was a former resident of Cerro Gordo is a guy named William Mulholland. Who was this guy and what did he teach you about the long-term consequences of short-term thinking?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, Mulholland was actually, he was from LA and he’s a civil engineer who brought water to the city when the city was running out of water. Back in the early 1900s, he was the head of what was then called Los Angeles Water Works, which eventually became the Department of Water and Power. And if you’ve ever seen the movie Chinatown with Jack Nicholson, that movie is kind of about the origins of LA’s Department of Water and Power. And so basically LA was outgrowing its water supply, the town was growing too fast, they had no where to get water. William Mulholland went out into the desert and he landed right below Cerro Gordo in the Owens Valley, where there used to be a place called Owens Lake.

And Owens Lake used to just be this massive lake. Imagine a lake that’s about seven miles across, 70 feet deep. As weather comes off of the ocean, it hits the Sierra Nevada, it kind of dumps all its weather on Mount Whitney and all that place. All that melts and goes into Owens River, which then turns into Owens Lake. And when Mulholland saw Owens Lake, he thought, there it is, the future to this city’s growth. And so Mulholland, through a variety of sketchy backdoor deals, eventually bought up most of the valley. So he bought the water rights from these different cattle ranchers that were living here. He even did things like, would seed to the newspapers that there was a huge drought coming, so these farmers were a little bit more encouraged to sell their property.

And then once he had all the water rights, he actually redirected the entire river to Los Angeles. He built what’s known as the LA Aqueduct. And by about 1918 or so, by redirecting the river, he left Owens Lake, which again, once was this seven mile across, 70 feet deep lake, dry. And a few decades later, he created… That turned into the largest producer of dust for the United States. And so me living above Owens Lake or the shadow of Owens Lake, I kind of see the dust bowl every single day. I see the end result of Mulholland’s wild dream. And I think that it’s impossible to ignore when you’re up here. And so for me, it’s kind of like a constant reminder that these things that I am doing in town, they are going to have long-term consequences outside of my lifetime. And so it’s an interesting story and it’s a place that I look to a lot.

Brett McKay: And you talk about in your experience in marketing, you worked with a lot of entrepreneurs where you saw a lot of that just short-term thinking, and it ended up biting them in the butt and other people in the butt in the long run.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, I just think that that’s kind of been the mentality for the last few decades. I think that like get in, get out, get your money and kind of move on. And I think that when I look at a lot of my friends, we kind of grew up in the era when you saw Mark Zuckerberg start Facebook, you know what I mean? And then cash out for or create a company that’s worth whatever it’s created today. And so that became almost the model for entrepreneurship. But again, kind of the premise there is always going in with the exit in mind, I think, which is kind of a backwards way of thinking about business, at least to me.

I think that what I found in Cerro Gordo, kind of speaking at what I talked about before about commitment, is a project that I want to stick with forever. I think that it’s very backwards to go into a company thinking from that origin how you’re going to sell it or who you’re going to sell it to. I think that there’s kind of like a lack of permanence there, there’s a lack of pride almost to it. And it leads kind of this deep feeling of dissatisfaction. So I think that if you can find that thing that you care about enough to care about the future, that want to work on it for a very long time, it’s just a lot more rewarding.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I’ve had that question popped to me a couple of times throughout my career doing AOM. Like, “What’s your exit?” And I’m like, “I don’t know. When I don’t have anything else to write about, when I die, that’s the exit.”

Brent Underwood: Yeah, I think… One of my buddies told me this once, he goes, “Does the owner of the Yankees have an exit plan?” And I don’t know if they do or not but I understand what he was saying. If you’re building something that you think is like world class, you really care about, why would you be thinking about the exit plan? Then you have to figure out what to do next. I would love to build something that sticks around, that we are proud of, that we are talking about a century from now or something.

Brett McKay: So you admit in the book while you begrudge Mulholland for draining Owens Lake, you kind of have a bit of admiration for him. Why is that?

Brent Underwood: I mean, what he pulled off was just amazing in a word. He was able to redirect a river 200 miles into Los Angeles and allowed Los Angeles to become what it did today. And that takes a certain type of vision, that takes a certain type of person, that takes a certain type of problem solver, that after spending a lot of time out in the desert, I have to have some admiration for. I think that the end result wasn’t ideal. I think it caused a lot of problems for a long time, but I think the scale of the project that he pulled off is admirable and if only for the scale.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Well, we’re gonna talk about this more, but he had high agency, he saw something and he made it happen.

Brent Underwood: Absolutely. I think that he was able to go out there, he set a goal for himself, and he achieved it. He wasn’t waiting for something to happen in LA to be better. He brought that sense of control into his own life. He wasn’t leaving things up to fate or luck. And I think to your point, that’s kind of what high agency means. It’s somebody that has that belief in their own ability to succeed at whatever they’re setting out to do. Even if it’s something as crazy as, I’m going to redirect a river 200 miles, which is just, it’s crazy to think about, but he was able to figure it out.

Brett McKay: Who were some other high agency people who lived in Cerro Gordo?

Brent Underwood: I think from the very beginning it was everybody here. The original owner of the town, Mortimer Belshaw, had to figure out a way to get a road up here. And again, right now I’m sitting at 8,500 feet in elevation and the valley floor below me is about 3,500 feet in elevation. So you figure there’s a mile of elevation gain to go here. And when he came, it was just a mule trail. But if this town was going to pull out $500 million of the silver, they obviously were going to have to have a lot better infrastructure than that. And so he just believed that he could make it happen, and he did make it happen. And because of that, it became the boom town that it was going to become. And I think that when I think about the different high agency people here, they all had that sense of control over their lives, that they could make things happen.

And during my time here, I remember my first year, we had a big tragedy here where we lost one of our main buildings. And when we were in the rebuilding process, the biggest hurdle that we had was to get concrete up to the town. And again, concrete might not seem like that big a hurdle but when you’re living up an eight mile dirt road that’s very far from everything else, the idea of having to get 10 truckloads full of concrete up here were very difficult. I called around and I asked all the local companies, like, “Hey, can you bring concrete up here?” And everybody was like, “No, road is too dangerous. No, road is too dangerous,” a variety of reasons. And so I kind of felt stuck. I called a helicopter company, they wanted some crazy amount to do it. And then through some of the YouTube videos I was making at the time, I got connected with this guy named Heavy D, who’s a guy named Dave Sparks in Utah.

I remember the very first call to Dave, he was just like, “I know, we’ll figure that out.” There was no like, even sympathy for like the routes I’d gone down so far, almost more of like, come on, man, we’re going to figure this out. And yeah, a couple of months later Dave purchased a concrete truck that we brought up here without any concrete in it. We bought a lot of dry concrete that we were able to bring up the road and we mixed and poured essentially about 10 truckloads worth of concrete in a single day to pour the foundation of the hotel that we’re building right now. And it just kind of like unlocked that feeling within me that, hey, these things are figureoutable. I think that’s a term that I think about a lot up here is that the skill of figuring things out is a muscle almost and it grows the more you use it.

And I think that when I first got up here, maybe it’s, “Hey, can I figure out how to build a little porch on one of the cabins?” And after I did that, I was like, “Oh, maybe I can fix the roof.” And after Dave came, I was like, “Oh, I just poured 10 truckloads of concrete on the top of a mountain in the middle of nowhere. There’s almost nothing that I can’t do then.” And I think that the confidence grows within that, like each time you figured out something a little bit harder and a little bit harder and a little bit harder, that sense of agency that we talked about shines through more and it almost changes your belief about yourself. Now I feel like I am somebody that is going to figure out whatever Cerro Gordo throws at me. And I don’t think that I felt that four years ago before I moved here.

Brett McKay: Yeah, this idea of having a sense of agency, as a dad, that’s the big thing I’m trying to inculcate in my kids. I want them to have that idea or that sense that any problem they have, it’s figureoutable. You can figure it out. You don’t have to be passive, you can do something about it.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, I think that that term passive is almost what I was trying to fight against coming up here. I think that that feeling of helplessness is one that nobody likes to feel. And I think that the answer out of that is trying to figure out different little problems. And again, kind of developing that muscle as you go, figure that figureoutable sense. And I think that at Cerro Gordo it’s kind of like trial by fire, I had to figure that out time and time again. But now I feel that because the agency grew again, like, your confidence grows. And you can see it when you know people. I’m sure everybody out there has like encountered somebody where no matter what problem you tell to them, they’re very calm. They’re usually very pretty quiet and they’re just like, “All right, we’ll figure it out.” It’s almost that feeling you get if you’ve ever been around like special forces people.

And for me, I think about people that I’ve encountered in the desert, a lot of them have that kind of calm, coolness to them. And when I first moved up here, I was very envious of that. I came from the online marketing world where everything was almost like a crisis to solve, that everything was very here now, how could we possibly do this? And up here, I just find that everybody that chooses to live in the desert, chooses to live pretty far away from a traditional support system, has a very high sense of agency. And I feel that living up here, that’s one of the most important things I would say that it developed over the past year past four years.

Brett McKay: So you experienced a lot of setbacks in your pursuit to restore Cerro Gordo. You mentioned a big one. The biggest one probably is the hotel burned down. This was going to be the crown jewel of the town. What were the emotions you went through when you saw this hotel on fire?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, it was the main crux of all the plans here. It was this beautiful hotel from 1871 that was kind of going to be the gathering point for the cabins we were going to put up. This is where everybody was going to experience, take photos, enjoy the place. And the day it burned down, it just felt every feeling all at once almost. It was a, it was seeing your hopes, your dreams, and like the majority of your life savings go up in flames all at once. And it was difficult. I remember after it, I didn’t really want to be here, but I didn’t want to be anywhere else. I felt very sad, I felt disappointed, I felt like I let history down because at that point I was very deep in the history here. And like we talked about, the lineage of things that had happened and this had happened on my watch. And I remember the first day just sitting on the porch still in pretty bad shape when the old owner of Cerro Gordo, the guy that had actually sold it to us, came up because he had heard about the fire.

And I remember when I saw him, I thought he was going to just lay into me for a bunch of different reasons. And I remember in the moment, he kind of put his hand on my shoulder and he said, “Listen, this was bound to happen. You can’t change what happens, but what happens from here is up to you.” And I remember in those moments, you kind of look for something to grab onto. And that was kind of a phrase that I grabbed onto for a long time, like what happens from here is up to you. Because I think it’s true, it seems very basic when you say it out loud, but no matter what the circumstance you’re in, what happens next is up to you. And so for me, I could have gone back to Austin with a tail between my legs, I could have thrown in the towel. It probably would have been the better move financially and everything like that. But then I think about the guys like Burro Schmidt, like finishing what you started, like leaving something behind and we’re here.

I’m looking at my window right now and I’m looking at the hotel and it’s back, there’s a roof on it. We’re doing some of the plumbing right now inside of it and it’ll be open soon. And I think that’s, again, one of those agency things where when I look at that, I think of all the difficulty that went into rebuilding it, but that we finished it, I kind of think back to earlier in my life of like, when didn’t I push myself and what things didn’t I finish that maybe I could have? And how could have those changed the direction of my life earlier on? And so what originally was by far the biggest tragedy here, it kind of turned into the battle cry, the marching orders for a long time. And now that this thing is standing again, I feel like what could Cerro Gordo possibly throw at me that I couldn’t handle?

Brett McKay: So you started rebuilding the hotel and that’s on its way, and again, you had to exercise some agency to do that. You also talk about in the book, you reached a point with this project, so you started working on it in Gusto in 2020, you’re up there non-stop working all the time, and you started experiencing some burnout, what did working on this town teach you about burnout and how to manage it?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, I think that once you find that project that grabs your attention, doesn’t let go, that thing that just captures all of you, it can consume you in some ways. For me, I don’t think I left the town for more than a day for two or three years. And it was just like every day working as hard as we could, rebuild this hotel, rebuild this hotel. What happens next is up to you, what happens next is up to you. And I lost like 30 pounds. I wasn’t a guy that could probably lose any weight to begin with. I just got really bad place mentally. It was just every day kind of waking up and just being consumed by this project to the point where a lot of my friends are calling and are like, “Dude, like you need to relax. This is not going to work.” And I just kind of got to the point where I realized that if I were to flame out, burn out completely, then it would kind of suffer the project in total.

Then I look back again to the lineage of guys that were here before and when I dug deeper into the history of the Mortimer Belshaw or the L.D Gordons that lived and managed this town back in the day, they all had a time away, you know, they were able to go away, kind of reflect on what they were doing and come back to it. And so I think for me, I try to develop a little bit of a rotation these days, you know, where I am here probably a month straight and then I try to take at least three or four days off the mountain every couple of times, because it also provides us perspective where you’re not so stuck in it. And that, originally I felt guilt for that. I thought, every day that I’m not at Cerro Gordo is a day that progress isn’t going to be done. But eventually you get to the point where if you’re so burned out, there’s not progress happening even when you’re there. And so I think that like some healthy retreat is almost necessary when you get into one of these giant projects.

Brett McKay: Yeah. You talk about, you found a book in the Belshaw house in the town. It was about World War II and you flipped through it and you found this section about how they rotated soldiers on the front line so they could avoid battle fatigue.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, it was a requisite. It was prescribed to them that there was going to be a set number of days you could be on the front line, then there’s a set number of days you had to be in the very back, then a set number of days you’re kind of in the middle. And this is the way they’re able to prevent this horrible burnout of these soldiers in war. And I don’t think that any of us are in a situation akin to being soldiers in war, especially me rebuilding a town that I live in, but I do think that there was lessons to pull away from that to where, them, even the kind of the most experienced soldiers out there needed that little break. And that was comforting in its own way for me to take a little bit of time away.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So if you’re working on a big project, make sure you rotate yourself off the front line regularly. You also talk about how this town taught you a lot about humility and developing a sense of awe. Tell us more about that.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, the town’s set in just one of the most beautiful settings I can imagine. If I look out my window right now, I see Mount Whitney, which is the tallest point in the lower 48. I see the Sierra Nevada, I see Owens Lake. And if I turn my head the other way, I see all of Death Valley beyond me, the desert just as far as I could possibly see. And it’s just awe-inspiring. I think awe is one of those terms that’s thrown around far too often these days. Not everything is awesome, even though we say that kind of is almost the knee-jerk response to when somebody texts us something, we’re like, “Oh, that’s awesome.” But true awe, to me, is something that just stops you in your tracks and instinctually tilts your head up. It is that giant mountain that makes you feel small. It’s that desert for as far as you can see. It’s even being in a concert with musicians that are just amazing. You can get that sense. And for me out here, at least in the mountains, it just reminds me of your place in the world.

There’s a Stoic term called sympatheia, which is basically talking about the interconnectedness of it all. And there’s a Marcus Aurelius quote that says, what hurts the hive hurts the bee, basically, what’s bad for the world is bad for you individually as well. And so I think that taking that time and zooming out and understanding how your life, your project, or whatever fits into the world allows you to put your problems into perspective. It kind of allows you a little break from that, oh man, my problems are everything, this, this, and that. And for me, being out here in the nature, it just, it brings me to that place of mine that I haven’t found anywhere else. Living in Austin, I never found those places where it was truly awe-inspiring and it brought that sense of peace to me. And I think that like, it was just a constant reminder to get out in nature as often as I could.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I love going to the desert, that’s my place where I go when I need to restore myself. I just love the emptiness of it. I love seeing big mountains in the distance, I love seeing the mesas. There’s a solace in such a desolate place. I don’t know, it just recharges me. I love… I’m actually planning a trip to get out to the desert now and I’m looking forward to it.

Brent Underwood: Yeah, it’s just, it’s also, for me when I think about the desert I just feel like there’s nowhere to hide, it feels very honest to me is the word I look about when I think of the desert just because like everything’s kind of laid out in front of you and it just goes and goes and it just leaves you that time to think, there’s not a lot of distractions, not even as much color as you’re used to when you look at a hillside or something and so it just like, I don’t know, it’s amazing.

Brett McKay: What’s the future of Cerro Gordo? Where can people learn more about it, what you’re doing?

Brent Underwood: Yeah, so I’m hoping that this year we finish up the hotel. That’s been a big project over the last few years. We’re going to add some cabins over the coming years, maybe some campsites as well. But we’re open to the public every day. If people want to come up and check out the town, we’re open from 9:00 to 5:00. There’s no charge for people to come up. I’ve made a little museum of different artifacts that I found on my hikes or down in the mines that people can check out. So hopefully this year we introduce long-term accommodation or overnight accommodation. And then long-term, who knows? I would love to see this place stick around for a few more generations so people can keep being inspired by the history and the beauty here. And I kind of document all of it on my YouTube channel, which is just called Ghost Town Living, which is the same name as the book, Ghost Town Living, which chronicles the past four years here. So that’d probably be the best place to check out.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Brent Underwood, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Brent Underwood: Of course. Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Brent Underwood. He’s the author of the book, Ghost Town Living. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find more information about his work at his YouTube channel, Ghost Town Living. Check that out. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/ghosttown, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles that we’ve written over the years about pretty much anything you can think of. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it if you’d take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcast or Spotify, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support and until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.