Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius was one of the last Stoic philosophers and today is arguably the best known. Thanks to his personal writings that eventually became Meditations, Marcus left us with concrete exercises to put Stoicism into action.

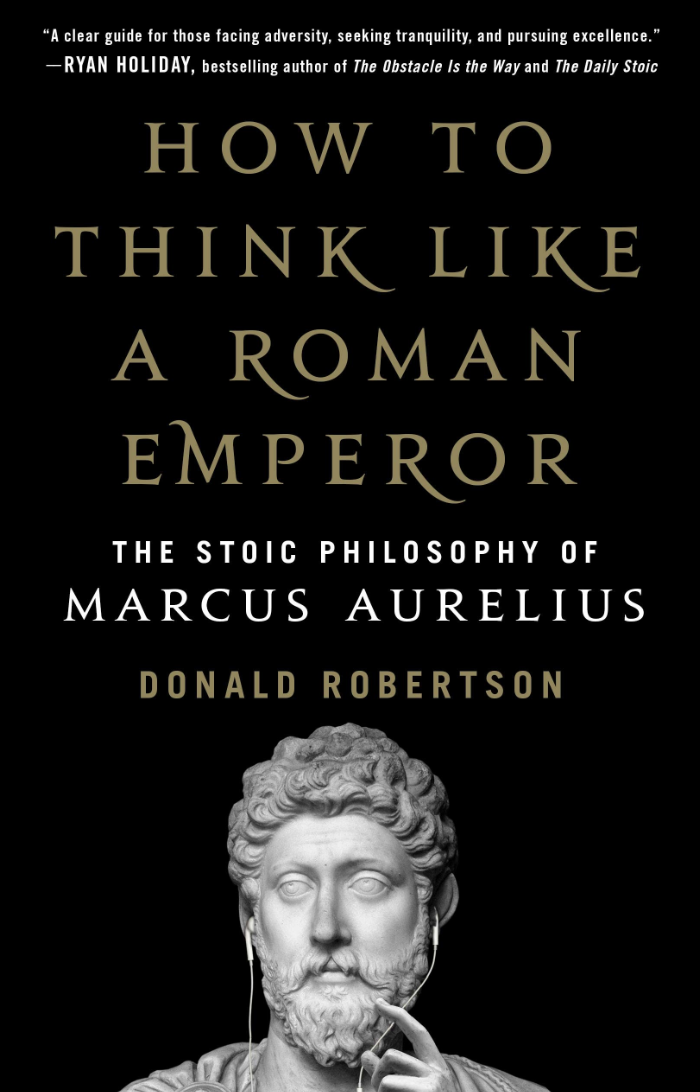

My guest today explores this Stoic tradition and connects it with modern psychotherapy in his book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius. His name is Donald Robertson, and he’s a Scottish philosopher and cognitive psychotherapist. We begin our conversation discussing the history of Stoicism and the overlooked beliefs the Stoics had. We then discuss the end goal of Stoicism and how it differed from other ancient philosophies like Aristotelian virtue ethics. Donald then explains the Stoic approach to emotions and the common misconceptions people have about Stoicism in that regard. We then dig into Stoic practices taken from Marcus Aurelius and discuss how modern cognitive psychology backs them up. Donald shares how the Stoics used language and daily meditations to manage their emotional life, and how they went about the psychology of goal-setting and dealing with success and failure.

Show Highlights

- The origins of Stoicism — Where did it start? Who were the founders?

- Comparing Stoicism to Aristotelian ethics

- How did the Stoic way differentiate between good and bad actions?

- The connection between Stoicism and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- The Stoic approach to emotions (and misconceptions about it)

- How our language can help us manage our emotions

- How Stoics view anger and why they use so much space talking about it

- Marcus Aurelius’ story, including his circuitous route to becoming emperor

- On catastrophizing

- What does Stoic meditation look like?

- Was the Apostle Paul a Stoic?

- What do Stoics say about changing or moderating our desires?

- What about worry and anxiety?

- Balancing successful outcomes with successful tactics (and dealing with setbacks)

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Meditations on a First Reading of Meditations

- The Albert Ellis Institute

- 5 Ancient Stoic Tactics for Modern Life

- Zeno of Citium

- Scipio Africanus the Younger

- Cato the Younger

- An Introduction to Stoicism

- Aristotle’s Wisdom on Living the Good Life

- Meditations on the Wisdom of Action

- You May Be Strong, But Are You Tough?

- Epicureanism

- On Anger by Seneca

- Quit Catastrophizing

- How to Deal With Anxiety?

- My interview with Ryan Holiday about obstacles

Connect With Donald

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius is one of the last Stoic philosophers and today is arguably the best known. Thanks to his personal writings that eventually became the Meditations, Marcus left us with concrete exercises to put Stoicism into action. My guest today explores this Stoic tradition and connects it with modern psychotherapy in his book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius. His name is Donald Robertson and he’s a Scottish philosopher and cognitive psychotherapist.

We begin our conversation discussing the history of Stoicism and the overlooked beliefs that Stoics had. We then discuss the end goal of Stoicism and how it differed from other ancient philosophies like Aristotelian virtue ethics. Donald then explains the Stoic approach to emotions and the common misconceptions people have about Stoicism in that regard. We then dig into Stoic practices taken from Marcus Aurelius and discuss how modern cognitive psychology backs them up. Donald then shares how the Stoics used language and daily meditations to manage their emotional life, and how they went about the psychology of goal-setting and dealing with success and failure.

After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/marcus. Donald joins me now via clearcast.io.

Donald Robertson, welcome to the show.

Donald Robertson: Thanks very much, Brett, it’s a pleasure to be on.

Brett McKay: So, you are a psychologist and a philosopher, and the author of the latest book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius. So, I know our listeners are familiar with Stoicism, but I’m curious, how did you discover Stoicism? Was your career as a psychologist, is that what led you to Stoicism, or was it something else?

Donald Robertson: Well, I’m actually a cognitive behavioral psychotherapist, and I kind of got into Stoicism around the same time that I began training in therapy. So, really, the whole story started when I was a teenager. My father passed away when I was about 13 years old. I was kind of searching for meaning, so I started reading lots of self help books and stuff like that, and I started reading religious texts, I started looking at Christian Gnosticism, and the Gnostics were influenced by Plato and the Neoplatonists. So, that got me into reading the classics, and I went to university and studied philosophy, and I was really searching for a way to bring together my interests in self-improvement and philosophy, and kind of understanding the meaning of life, and all that kind of stuff. It was only really after I graduated from philosophy that I stumbled across the Stoics. I went back to read more about Neoplatonism, and I found a book about Plotinus, the Neoplatonist, by a French scholar called Pierre Hadot.

Hadot focused on identifying the psychological or spiritual exercises that he found in the classics, and I immediately realized that these were similar to techniques that we use in modern psychotherapy, and I kind of had an epiphany, and I realized that the stuff that Hadot was talking about in Classical philosophy dovetailed very neatly with modern psychotherapy, so I started researching that area.

Brett McKay: So, was there a crossover with Stoicism into your career as a psychotherapist?

Donald Robertson: Yeah. I mean, cognitive behavioral psychotherapy was originally kind of inspired by Stoic philosophy. Albert Ellis, who developed this thing called rational emotive behavior therapy, or REBT, in the 1950s, he was the main precursor, pioneer of modern CBT, and he was originally a psychoanalyst, but he became disillusioned with Freudianism in psychoanalysis. He kind of gave up on it and tried to start again from scratch, which I always think is a really admirable thing for somebody to do in the middle of their career. He thought, “I’m going to have to reinvent this. It’s not quite working for me.” He’d read the Stoics as a teenager, and he started to draw inspiration from Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus, and developing this new cognitive approach to psychotherapy.

So, all cognitive behavioral therapists actually know a famous quote from Epictetus, which we’re bound to talk about today, which is, “It’s not things that upset us, but our opinions about things.” That encapsulates what we call the cognitive theory of emotion, the idea that our emotions are largely, if not exclusively, shaped or determined by certain underlying beliefs, and as soon as we view emotion in that way, it opens a whole repertoire of therapeutic techniques, because we can start asking people what their beliefs are that underlay their emotions. We can heighten their awareness of those, and we can start questioning the evidence for and against the beliefs that shape their emotions. So, that allows us to do cognitive therapy. That was normally introduced to clients in a simple way, just by teaching them that quotation from the Stoic Epictetus.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about Stoicism now. You used Marcus Aurelius to explore Stoic ethics and practices. Before we get to his life, because he was the last of the great Roman Stoics, we’re kind of starting at the end there, there’s a whole history of Stoicism before that. Can you give us sort of a brief thumbnail history of Stoicism? Like where did it start, who were the founders, and all that.

Donald Robertson: Okay, well, let’s compress 500 years of history.

Brett McKay: Right. You can do it.

Donald Robertson: .. 30 seconds or something, right? Well, the first thing is Stoicism lasted five centuries. It was founded in 301 B.C. by a Phoenician merchant called Zeno of Citium, who was shipwrecked near Athens. He studied different philosophies in Athens at the time, and he was particularly inspired by Socrates. There’s a bit of debate about this, but I believe that Stoicism is a Socratic philosophy. It’s a kind of resurgence of the original Socratic philosophy, and that’s where I think many Stoics saw what they were doing. Zeno founded this school of philosophy, and it continued for many centuries all the way down to Marcus Aurelius, and he’d originally trained as a cynic philosopher, like Diogenes the cynic, in that tradition.

The Stoic school was very egalitarian. The Stoa Poikile is a kind of porch, or an arcade, where he lectured on the edge of the Agora, the Athenian marketplace, where Socrates had taught before him, so it was out in public. The Stoics taught men, and women, and Athenian citizens, and foreigners, and rich, and poor. It was much more open than other schools of philosophy, which had retreated to the gymnasia, kind of like retreating to the ivory towers. So, Socrates had taught in the marketplace, the Stoics basically did the same thing, and you can see the very name of Stoicism kind of implies a philosophy of the street, as it were. It took place out in the marketplace, once again, where Socrates had previously taught.

The Stoics’ main idea is that virtue, which we’ll probably come back to and elaborate on more, but the essence of it is that the goal of life is attaining a kind of moral wisdom that improves our character. The Stoics called it aretai, or it’s usually translated as virtue, or excellence of character. So, the most important thing in life is a sort of self-improvement that strengthens and improves our character, and it’s synonymous with a kind of practical or moral wisdom. And so therefore, the Stoics are relatively indifferent to the ups and downs of external fortune, poverty or success, friends and enemies, these things are seen as less important compared to our own strength of character.

Brett McKay: How did Stoicism go from Greece to Rome, 500 years later?

Donald Robertson: Well, funnily enough, there’s a simple explanation for that. There was a succession of leaders who took over the Stoic school, and one of them, a guy called Diogenes of Babylon, in 155 B.C., went on an ambassadorial mission from Greece to Rome, along with a couple of other philosophers, and he became a kind of celebrity. The Romans thought he was really interesting, that he was bringing Greek culture to Rome for the first time, and teaching them about this weird philosophy called Stoicism. Of the various philosophers that came to Rome, the Stoics had the biggest impact, in a sense, because the Romans felt that Stoicism really resonated with traditional Roman Republican values, and so Stoicism became trendy at Rome.

Shortly after that, a famous Roman statesman and general called Scipio Africanus, or Africanus the Younger, became a follower of Stoicism in an intellectual circle that surrounded him, called the Scipionic Circle, embraced Stoicism. And then that became a tradition of Roman noblemen, politicians, intellectuals, embracing Stoicism, all the way down to Marcus Aurelius.

Brett McKay: So yeah, Cato, Seneca, other examples of statesmen and philosophers. Well, maybe we can get this in a little bit later, but I imagine, did Stoicism change when it went from Greece to Rome? It’s not set in stone, the Stoic philosophers have been willing to change it, to refine it.

Donald Robertson: No, they argued with each other, there were schisms within the school, so we know that there was a certain amount of flexibility in the school, and it was around for such a long time that… I mean, psychoanalysis was only really around for less than a hundred years, but Stoicism was five centuries, so it had to kind of evolve, and it spread all over the place, throughout the empire. But it’s difficult for us to pinpoint exactly how it changed, because hardly any of the early Stoic texts survived. Most of the main texts that we have, all of them intellectually come from the late Roman period, the Roman imperial era, like Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and so on.

So, we can kind of infer that the earlier Stoics were sort of more interested in logic and stuff, and the later Stoics seem more interested in philosophy as a way of life, or ethics, but it’s not entirely clear how significant that difference is, because we don’t know that much about the early Stoics, unfortunately.

Brett McKay: So, when people think of Stoicism today, they often think about the ethics, how to live a good life, but as you said, there was Stoic logic, there was Stoic metaphysics, Stoic theology. I’m curious, did those things, like the metaphysics of Stoics, or their theology if you want to call it that, did that influence their ethics?

Donald Robertson: Yeah, it did. We should say, the Stoics thought of their curriculum, their philosophy, as consisting of these three chunks, physics, ethics, and logic, and they thought of them as being closely interconnected in a number of ways. Again, we know more about Stoic ethics because the books that survive are mainly dealing with that aspect of Stoicism, and our knowledge of physics in Stoicism is a bit more fragmentary. Stoic logic we only really know a few fragments about from other authors, really.

Let’s take the physics, for a start. The essence of it, really, is that Stoics were pantheists, and that means that they believed that the whole universe, the universe in its totality, is sacred and divine. So, it was a kind of more naturalistic conception of God. God isn’t this guy sitting in a cloud, or this mysterious metaphysical being in another realm, God is just the universe considered as a whole. And so, they refer to that as nature, which is also synonymous for them with Zeus. Zeus is just the kind of personification of nature as a whole.

And so, Stoicism was this kind of strange, materialistic, pantheistic, kind of slightly mystical philosophy, but one of the implications of that is that the Stoics, particularly Marcus Aurelius, think that one of the big risks that we run in life is becoming alienated or isolated from the bigger picture. So, one of the goals of Stoicism is to develop a greater sense of oneness with the universe as a whole, and a greater sense of kinship or oneness with the rest of humanity. And so, they think that kind of underlies our moral and our spiritual development. It’s linked in with this metaphysical vision, that the reality for us and what’s sacred is the totality considered as a whole.

Brett McKay: There’s parallels there to Eastern philosophies like Buddhism.

Donald Robertson: Oh, yeah, totally. I mean, from a modern perspective, Stoicism and other Hellenistic philosophies appear like yoga, or Buddhism, or something like that, or other mystical religions from the East, although we can also see differences between these different traditions.

And then, in terms of logic, funnily enough, having said that, the Stoics were way ahead of their time. They developed a kind of propositional logic, which was only really rediscovered in the late 19th century by people like Bertram Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein, for example. So, modern logic is very indebted to the Stoics, it’s really a resurgence of something they discovered nearly two and a half thousand years ago. But for them, logic was broader than what we think of as formal logic today. So, it included doing a precursor of what we think of as formal or propositional logic today, but it also encompassed thinking about the nature of language and reasoning in a wider sense, and it also encompassed the use of language in rhetoric, and understanding the relationship between thought and reality, for instance.

So, the way that that intersects with ethics is that the Stoics thought it was important to apply logic to everyday problems, not just use it in a kind of abstract sense. So, they would practice thinking rationally and logically about moral problems that they faced on a day to day basis. So, in a sense, Stoicism is also a philosophy that’s about thinking clearly and rationally about everyday life, and embracing a sort of realism and objectivity, and a sense of the bigger picture, in our thinking.

Brett McKay: We’ll get into the intersection of language and the ethics here in a bit, because I thought that was an interesting section you had in the book, but let’s talk about the ethics. So, you mentioned earlier the telos, or telos, as Aristotle would say, of Stoic ethics is aretai, or virtue, or excellence. So, I had mentioned Aristotle, was the Stoic concept of virtue, was it similar to Aristotelian virtue, or was it different?

Donald Robertson: Well, from our perspective, we might see them as kind of similar, but in the ancient world they were viewed as fundamentally competing philosophies. One of the cool things about ancient philosophy is that people thought of different schools of philosophy as representing fundamentally different perennial attitudes towards the meaning of life. So, Aristotle, for instance, thought that the goal… or it seems this is what Aristotle taught, anyway, certainly his students taught this. The Aristotelian school thought that the goal of life was to have a kind of combination of internal and external goods. So, by internal goods we’d mean strength of character, wisdom, virtue, and so on. But they also thought it was important to have friends, and wealth, and material possessions, and stuff like that.

The Stoics question that, but they question it in a kind of subtle way. So, for Stoics, external stuff is important, but it’s not essential to the goal of life. So, somebody can attain complete fulfillment in life, according to the Stoics, even if they’re surrounded by enemies, they’re sickly, and persecuted, and they’re living in poverty, for instance, Socrates, who was persecuted politically and executed, and lived in poverty. So, the Stoics would say, well, giving him money, and more friends, and a reputation wouldn’t necessarily make Socrates’s life better. In a sense, what made him a great man and what made his life so fulfilling was that he faced all these disadvantages and he engaged them with strength of character and wisdom.

Brett McKay: How did the Stoics figure out what was good or virtuous, or what was bad or vice? So, Aristotle had his idea of using the golden mean to sort of figure out the right thing to do at the right time for the right reason, so it was kind of situational in a way. Was the Stoic, was it a little more, I don’t know what’s the right word, not situational, but sort of more of a Platonic ideal that Socrates talked about?

Donald Robertson: I mean, for the Stoics, there’s two aspects to it. In one sense, it’s much simpler. In another sense, it’s more complex. So, for the Stoics, very simply, the most important thing in any situation is to act with wisdom and justice, or to act with virtue, moral practical wisdom as they understand it. So, our character, our intentions, are the most important thing in any situation, and then whether we succeed or fail, whatever befalls us is relatively trivial by comparison.

But what it actually means to act with wisdom and justice may vary from situation to situation, and different Stoics may actually disagree with each other about what would constitute justice in different situations. Maybe sometimes we can’t say for certain whether it’s virtuous to give money to a beggar in the street or not, because there’s things that we might be uncertain about the outcome, for example. There are elements of judgments of probability, and so on. It’s a complex question. There’s not a kind of one size fits all answer maybe, but the key thing is that we are acting with the intention, fundamentally, to do good, and that’s the overriding concern for Stoics. How we apply that in practice is something that might be up for debate.

Brett McKay: So, you mentioned earlier that… So, Aristotle, his idea of the good life, a flourishing life, eudaemonia, it was a combination of internal factors and external factors. For Aristotle, the idea was to become like this Greek gentleman, which required you to have health, wealth, reputation, et cetera. The Stoics, contrary to I think popular belief, they weren’t against those things, they just treated them differently. How did they approach those external things in life?

Donald Robertson: Well, the best explanation for this, in a way, is in Socrates, in the dialogues that we have from Xenophon and Plato. In Socrates, we kind of get more arguments for some of these ideas, which we see the Stoics then putting into practice, as it were. The Stoics are influenced by these arguments provided by Socrates and other earlier philosophers. So, in one of the dialogues, called the Euthydemus, Socrates argues that look, people think that wealth, and friends, and health, and all these external things, constitute good fortune, like they’re good things, but Socrates says look, all of these things could be used badly by a foolish person, or a vicious, a bad person.

Money, for example, is an easy example. So, in the hands of a wise and good person, money can be used philanthropically, to do good and wise, prudent things. But in the hands of a foolish person, money can be used to do lots of foolish and terrible things.

So, these external goods are actually not really intrinsically good in themselves. They just offer us practical advantages, or opportunities to exercise more control over our environment, and that could be done well or it could be done badly. And so, Socrates concludes from that that the only truly good thing is wisdom itself, because that determines whether we use other things well or whether we use them badly.

Brett McKay: So, these external things are indifferents. There’s preferred indifferents, so that’s like health, money, et cetera, and there’s unpreferred or dispreferred indifferents, so that’d be things like sickness or poverty. So, you don’t want sickness or poverty, but you’re not going to get upset if that happens, or you want health and wealth, you prefer that, but you’re not going to spend all your time and energy going after it.

Donald Robertson: Also, it’s variable. It’s reasonable to pursue the preferred things and avoid the dispreferred things, so it’s reasonable to pursue wealth and avoid poverty, within certain limits, according to the Stoics. So, the limitless pursuit of wealth would be irrational according to them. Sometimes, enduring poverty may actually strengthen our character, it might be a good thing. Likewise, we avoid pain, it’s reasonable to do that, but sometimes enduring pain and discomfort might be good for our health, and might strengthen us, like taking cold showers and things like that might be something that people do because they think it’s beneficial, or undergoing surgery might be painful, but we do it because it’s beneficial for us. So, the Stoics would say it’s kind of variable, and we need to use reason to judge when something’s preferred and when it’s dispreferred, although we can make some broad generalizations about them.

Brett McKay: So, a large part of Stoic ethics is about managing emotions. Desire is one of those emotions, anger, worry, et cetera. This is kind of where that intersection with your work as a psychotherapist comes in. What was the Stoic approach to emotions, and what are some of the misconceptions people have about Stoics and emotions?

Donald Robertson: Well, I guess the main misconception is that people think Stoics are unemotional, and I should probably explain, the easiest way to explain that is many terms from Greek philosophy degenerated in their meaning over time. We usually denote that by using a capital letter, or writing them in lowercase letters. So, Epicureanism, with an uppercase E, capitalized, is a Greek school of philosophy that’s kind of nuanced and complex, but to be an epicurean today, with a lowercase E, just means enjoying expensive food and stuff, like being a gourmet or whatever, so it’s a much more simplistic, it’s almost a caricature of the original idea.

The same is true of Stoicism. When we talk about someone being stoic today, with a lowercase S, we just mean that they’re kind of tough-minded, unemotional, they’ve got a stiff upper lip, and Stoicism with a capital S is, as we’ve seen already, this big, complex, 500 year school of philosophy that embraces physics, ethics, and logic, and is much more nuanced in its approach. Actually, being stoic, with a lowercase S, not only is a simplification of what Stoicism says about emotions, but it may actually fly in the face, sometimes, of what the Stoics were advising.

So, someone who’s trying to be Stoic might try to conceal or suppress painful emotions, and that’s against Stoicism. The Stoics believe that the initial involuntary aspect of emotion, which they call propatheiai, the proto-passions, our first movements, are indifferent. They’re neither good nor bad, and so we should accept them as natural and kind of embrace them, let them wash over us in a sense. What they’re really concerned with is getting us to change what happens next, the way we respond to our initial emotional reactions. Do we perpetuate them, do we amplify them, or do we start to question them and reappraise them?

That’s exactly what we do in cognitive therapy. We teach people to accept their automatic thoughts and feelings, because they are outside of their direct control, to allow themselves to embrace those feelings rather than trying to deny or suppress them, but then to change how they subsequently respond to them. So, when people are depressed or angry, they tend to ruminate, they dwell in negative thoughts and amplify them. But that’s under voluntary control, we can stop doing that or change the way that we think about things.

The Stoics, rather than trying to eliminate all the negative emotions, want us first of all to kind of be indifferent towards and accept these automatic initial reactions, but they also want us to question our unhealthy, irrational, and excessive emotions, such as extreme anger, and replace those with healthy emotions, which they call the eupatheiai, so love, and joy, and variations of those feelings, and also even a healthy feeling of shame or aversion. So, they think a wise man has a natural feeling of aversion to doing things that are dishonorable or beneath him. So, they think even some painful emotions might be healthy for us and consistent with wisdom.

So, the ideal for a Stoic isn’t to be unemotional, it’s to rather replace unhealthy emotions with healthy ones.

Brett McKay: Was there ever an instance where the Stoics would say that maybe anger was useful? Like Aristotle would say, anger’s not completely useless or bad, as long as you have it in the right place, at the right time, for the right reason, anger can be productive. Did the Stoics have that idea, or were they say yeah, anger just is not even useful, don’t even go there?

Donald Robertson: Yeah, they disagree with Aristotle. It’s really cool, actually, that we have this debate in the ancient world, because even today people still can argue about this a bit. So, it’s a cool debate, it’s an interesting debate.

Seneca wrote a whole book called On Anger. The Stoics were really interested in anger. Today, psychotherapists are mainly interested in depression and anxiety, and less so in anger. The Stoics were more interested in anger than any other emotion. Marcus Aurelius talks about it a lot, and Seneca has this whole book on it that comes down to us today. In that book, he talks about Aristotle’s idea that a certain amount of anger might be useful, or healthy, and Seneca says, “No.” He disagrees with that idea.

But he disagrees for very subtle reasons, which kind of depend on the Stoics’ definition of anger. So, the Stoics define the emotions cognitively, based on the underlying beliefs that shape them. And so, the Stoic theory, and we do this in modern cognitive therapy as well, so the Stoic theory is that anger, as they define it, is based on the belief that someone deserves to be punished, or harmed, in other words, for a perceived injury or transgression. It’s about revenge, basically, anger, fundamentally, is a desire for revenge, the Stoics would say. They would argue that it’s never rational to fundamentally want to harm another person.

Now, you might punish someone in a more superficial sense if you think it’s going to reform them, or educate them, or be in their interests, but that would be different, because there, your fundamental goal is actually to help the other person, to educate or improve them. But if your fundamental goal is to try and hurt them, the Stoics would think that’s really what anger is about, is harming someone for the sake of it, and it’s never rational or justifiable to want to do that. So, they say there might be things that resemble anger, but they don’t fit our definition.

Seneca even at one point says look, if someone comes up and punches you in the face, your blood pressure’s going to rise, and you have this kind of animal-like reaction of anger that’s automatic, and Seneca says that’s not really anger in the sense that we are talking about. That’s an automatic reaction, and we treat that as inevitable and natural, but we would then question how we’re going to respond next, and whether we want to lash out at the other person, or whether we want to try and understand what’s going on, and rectify things in a rational way.

Brett McKay: Okay, so yeah, the Stoics, not against emotion, but they want people to think about it, reason their emotions out. All right. So, that’s sort of a broad overview of Stoicism. Before we get into specifics, let’s talk about Marcus Aurelius, because you use him, because his book, the Meditations, has all these wonderful insights on Stoic practices that he used to be a Stoic. How did Marcus discover Stoicism? Was he brought up in it, or did he discover it later on, when he was a young adult?

Donald Robertson: Well, some of this we have to kind of infer. I mean, a lot of people who read the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius don’t realize that what he’s talking about fits into this bigger philosophical tradition. What I’ve discovered is that a lot of people don’t realize that we know some things about Marcus’s life because of various Roman histories that survive, such as Cassius Dio’s, or Herodian’s, or the Historia Augusta, and other sources. So, we know some stuff about Marcus as well as what he tells us in the Meditations.

We know that… We’re told, anyway, that he started studying philosophy when he was 12 years old, which is an unusually early age. A Roman youth would probably only get into philosophy when they were about 15 years old, normally. Marcus got into it much earlier. It seems that he initially really embraced philosophy as a lifestyle. He dressed like a philosopher, he slept on a camp bed on the floor like a philosopher, and he began to act like a philosopher. We don’t know what sort of philosophy he’d enter. Sounds like it was probably either Cynicism or Stoicism or something along those lines.

And then we know that round about 15, he began his formal education in philosophy. We know who his teachers were because he tells us, but the histories also confirm that. We hear he studied under some of the most famous and important Stoic teachers of his day. He studied also the Platonic school of philosophy, and Aristotelian philosophy, and he read about the Epicurean philosophy as well. So, he was a very educated man, but it was only in his early 20s that he really embraced Stoic philosophy as a way of life, that he kind of fully converted to it.

Brett McKay: Was that because of his unique situation? Because what’s interesting about Marcus Aurelius, he wasn’t born to be the emperor of Rome. He kind of became that through some weird adoptions, and he kind of inherited the emperor title that way.

Donald Robertson: Yeah, it wasn’t really expected. It was Hadrian, the emperor Hadrian that chose Marcus to become a future emperor. It was part of a kind of long term succession plan, so there was another emperor between them. Hadrian chose Antoninus to succeed to him, who we know as the Emperor Antoninus Pius, and he in turn adopted Marcus Aurelius as part of this arrangement made by Hadrian. So, Hadrian knew Marcus as a young boy, and he originally had other plans for the succession, and then really, it was about a year before Hadrian died that he suddenly changed his mind and decided, “I want Antoninus to succeed me, and then Marcus Aurelius to succeed him. This kid, I want this kid to be the future emperor of Rome.”

We don’t know exactly what convinced Hadrian to do that. All we know is that Marcus said or did something at the court of Hadrian, as a small child, that earned him the nickname Verissimus, which means the truest, the most true, and that’s a play on Marcus’s family name, Verus, which means true. Hadrian says, “This kid’s not just true, he’s the truest of them all.” Something that this boy did convinced Hadrian that he needed to put him in place as the future emperor of Rome.

Brett McKay: I don’t know if we know this, because Marcus didn’t write about it or not, but do you think that idea that he knew he was going to be an emperor, I imagine that probably spurred him to study Stoicism even more. Maybe he was enamored at the idea of Socrates’s philosopher kings, right?

Donald Robertson: I think that was part of it, yeah. We’re told in the histories that Marcus used to go around courting Plato’s idea, the state will only flourish when philosophers become kings, or kings become philosophers, as he put it, and this was one of his favorite sayings, but I think maybe Marcus’s main teacher in Stoicism was a guy called Junius Rusticus. He was a very interesting guy in himself, and he was Marcus’s right hand man politically. He was the urban prefect at Rome, so he was kind of like a mayor, he was in charge of the administration in Rome. So, at Rome, Marcus’s right hand man, but he was also his main Stoic mentor.

He also appears to have been a friend of Marcus’s mother, Domitia Lucilla. So, she was a highly educated, extremely wealthy Roman matriarch. Her husband, Marcus’s birth father, had died when Marcus was only about three or four years old, so she took more responsibility for raising her son, and she seems to have known many intellectuals, to have been an educated and cultured woman, and it looks like maybe there’s a hint that she was friends with Junius Rusticus, so maybe she kind of steered Marcus towards Rusticus, as his main mentor or teacher in philosophy.

We also know that we’re told, surprisingly, that Hadrian was friends with the Stoic teacher Epictetus. It seems kind of unlikely, because Hadrian was really into sophistry and a very kind of pretentious and volatile man, so he seems exactly the type of person that Epictetus would have warned his students against. It may be also that Hadrian steered Marcus toward studying Stoicism.

Brett McKay: Well okay, so let’s talk about the insights about Stoicism we can glean from Marcus’s meditations. Going back to the idea of Stoic logic and language, you have a section on how our language can help us manage our emotions, the Stoic practice that we can get from that. So, what’s a Stoic practice that deals with language that we can take from Marcus?

Donald Robertson: Well, the main thing that the story… I mean, we’re told a little bit about this unlikely, and even in the ancient world it was thought paradoxical, that there was even a thing called Stoic rhetoric, but Zeno wrote a book on rhetoric. It was thought odd because the Stoics were known for speaking laconically, concisely, kind of abruptly. They used plain language, parrhesia in Greek. The word laconic, which we use today, comes from Laconia, the region in which Sparta was located. So, the Stoics were known for speaking like Spartans. Actually, the philosopher Cicero literally tells us that. We have a speech from Cicero where he talks about the Stoics, and says that they speak and act like Spartans.

So, we know that the Stoics wanted to speak concisely and objectively. They thought it was important to speak effectively, and in a way that was adapted to the needs of our hearers. So, we have to think about what other people need from us when we’re trying to communicate with them. We need to put ourselves in their shoes and empathize with our audience, but we also need to be honest with people, and avoid using flowery rhetoric, emotive language, and strong value judgments. So, the Stoic approach to language, basically, is to stick to the facts. The term that they use to describe that is this kind of obscure, technical term, phantasia kataleptike, which means having a firm grasp on reality. Sometimes it translates as having an objective representation of things. So, the Stoics practiced describing events in a very down to earth and objective manner, stripping away value judgments and assumptions from things.

Brett McKay: What insights from modern behavior psychology bolster this Stoic idea that our language can influence the way we think about reality?

Donald Robertson: Well, it’s certainly true. I mean, we tend today to talk about it more in terms of clients’ cognitions, or their thinking, but we only know about cognition because of the words that people use to express their thoughts. We know that people exhibit typical cognitive distortions. The cognitive distortions that people exhibit are forms of rhetoric, basically, such as hyperbole, some people use exaggeration or hyperbole. They use overgeneralizations when they’re talking about their problems, and they use metaphors to evoke emotion. So, that might be useful, like if you’re giving a speech and you want to really evoke other people’s emotions and stir them up, it could be useful to use flowery rhetoric and to play on language and stuff, but the problem comes when we start doing that in our own internal thinking.

So, I might say to myself, “Well, that guy really tore a strip off me at work today, and he shot me down in flames in front of everybody else. I felt like a complete and utter idiot.” And so, there I’m using very emotive language. I’m using metaphors, I’m using generalizations, and I could’ve just said, “Somebody disagreed with something that I said,” which just kind of seems really banal by comparison, but it’s obviously much less evocative of anger, and frustration, and distress. Sometimes we want to do that, when we’re giving a powerful speech, but why on earth would we want to do that to ourselves?

So, the Stoics think we fall into this trap of using rhetoric in our own thinking, and we need to be careful to take a step back from it, and practice describing things in some more banal, matter of fact, and down to earth terms, and doing that will damp down our emotions, and we’ll be able to see things in a clearer way.

Brett McKay: In fact, yeah, that’s one of the things that cognitive behavioral therapists do with their clients or patients, is help them start describing their problem in this more banal, objective frame, instead of that emotive way.

Donald Robertson: Yeah. We might say things like stick to the facts, just describe what you can actually see, and set aside all the other kind of flowery language and stuff, and notice how that makes you feel differently about things. So, we’ll often talk in therapy about decatastrophizing. That’s a kind of weird neologism that we use. It’s a clunky term, but it’s cool, because it takes a noun and turns it into a verb. So, the client might say, “This is a catastrophe,” and the therapist might say, “Well, is it possible you’re catastrophizing? So, is it possible you’re making it seem like a catastrophe because of the way that you’re describing it, the way you’re thinking about it, and the perspective that you adopt on it?” That makes clients realize that they have actually got more responsibility than they were assuming for the way that they perceive the situation. So, when we decatastrophize a situation, we usually have to get clients to describe it in more prosaic and down to earth language.

Brett McKay: Well yeah, and an example of catastrophizing, say someone loses their job. The next step they make is like, “Well, my life’s over. I’m going to lose my house, I’m going to be…” [crosstalk 00:36:48] And the therapist is like, “Well, just stick to the facts. What’s happened? You just lost your job, that’s it. That’s all we know.”

Donald Robertson: Yeah. Everybody’s favorite is, “It’s the end of the world,” right? Well, it’s never the end of the world, like Chicken Little, “The sky’s falling and all I know is it’s the end of the world.” Or, “This has completely destroyed my entire life,” somebody might say, because they’ve lost their job.

I’ll say very simply, as an aside, as a therapist over the years, I’ve often been surprised by the fact that for many people, being made redundant, losing their job, even being sacked from a job, may be one of the best things that happens to them, because otherwise, people often find themselves spending too much time in jobs that maybe aren’t ideal for them. And so, it might be short term pain that they go through, but ultimately, they often end up doing something that’s more fulfilling in life, in many cases. So, I’ve been surprised how often that losing a job might actually turn out to be for the best, in many people’s lives.

Brett McKay: Right, so it’s one of those indifferents. It could be preferred or not preferred, but you never know, right?

Donald Robertson: It’s the same as a relationship breakup, right? I mean, it seems like the end of the world, like when you’re with someone you love, and then the relationship comes to an end, especially if it ends badly, but then maybe some time later you’ll meet somebody else and have an even better relationship, that you would never had the opportunity for if the previous one hadn’t ended. Who can know what the future holds?

Brett McKay: You don’t, those aren’t facts, so you just don’t worry about it, that’s what the Stoics would say. We mentioned the parallels between Eastern philosophies and Stoicism. Stoics had a form of meditation that they would do, and Marcus describes it. What does Stoic meditation look like?

Donald Robertson: Well, what they didn’t do, as far as we know, is kind of sit cross-legged, and wear sandals, and burn incense, and focus on their breathing, and chant, and stuff. So, we don’t mean meditation in that kind of cliched sense, but even when we’re studying Oriental religions or philosophy, the concept of meditation is much broader than that anyway. So, that’s really a kind of caricature, an over-simplification of what meditation looks like.

So, we’re talking about meditation in a slightly broader sense. For Stoics, there are many contemplative practices that might be verbal, they might involve visualization, or they might involve more kind of abstract conceptual thinking. They’re a little bit different from what people might think of as meditation, but when people start practicing them, it becomes clear that it is a kind of meditative exercise, and the Stoics did them in a systematic, regular way. They talk about doing them on a daily basis, or frequently throughout the day, or every evening, or in response to certain situations.

So, Marcus is always telling himself, “Each day, remind yourself to contemplate your own death,” for example, or to think of each day as if it were your last, or another Stoic exercise we call prosoche in Greek, which means paying attention. It involves continually paying attention to the way that you’re using your mind, particularly your value judgments, and how those are interacting with your emotions and your desires. So, it’s kind of like Buddhist mindfulness in some ways, the Stoics have a similar concept.

The other one that’s popular in Stoicism, which is kind of unlike most meditation practices today, we call the view from above. Hadot, who I mentioned earlier, coined the term the view from above for it. That involves the Stoics trying to picture the whole of space and time, and their place within it, which obviously is impossible to do, but we can grasp the concept. In a way, we can think about the bigger picture to some extent. So, the Stoics would practice doing that in a number of different ways, broadening their awareness and broadening their perspective.

Again, like we mentioned much earlier, that’s kind of linked into the whole of Stoic physics, and the fact that they were pantheists, and believed the totality of the universe was the ultimate reality, and was sacred and divine. So, they’d rehearse picturing events from high above, for instance.

Brett McKay: So, the Stoic meditations, there are different types, but it seems like the common theme is, one is to see the big picture, like that sort of distancing helps you make your problems that you have not seem so big. It puts it in perspective. But also, it seems like there’s a lot of reflection going on, seeing where you can improve, where your faults are, and how you can do better the next day.

Donald Robertson: Well, actually, maybe just as an aside, there’s a passage in Marcus Aurelius where he says something really cool. He says that most of what he’s talking about can be summed up in Greek, six words, short words, a little phrase. “The cosmos is change, life is opinion.” Those two little statements refer to two of his favorite philosophers.

So, one is Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher who said “panta rei,” everything flows, the river of time. So, Heraclitus said that the universe is constantly changing, everything is in flux, and it’s from him that Stoics get their physics and this idea of pantheism. And so, Marcus says “The universe is change” in order to remind him of the transience of things, a bit like the Buddhist doctrine of impermanence. The Stoics, in many different ways, when they’re looking at the bigger picture, are also focusing on the smallness and transience of the current problems that we’re facing, and they think we become less distressed by events when we adopt that kind of perspective.

Another, “but life is opinion,” refers to Epictetus’s idea, that it’s not things that upset us but our opinions or judgments about them, and that’s the Stoic idea that we need to become more aware of our opinions, prosoche, pay attention to them and take responsibility for the way that our value judgments are distorting our perception of events, and shaping our emotions. So, Marcus says, everything he’s saying is encapsulated in these two little techniques, basically.

Brett McKay: So, one of the emotions that the Stoics thought a lot about on how to manage is desire, because desire can lead to vice, and frustration, and whatnot, what have you. I thought it was interesting, I was just reading in Romans this week, the apostle Paul, who probably studied Stoicism, you see some Stoic influence in some of his writings. He talks about wanting to do good, but he doesn’t do it, the good he wants to do, because he has this vice inside of him, the desire from temptation’s so strong. I thought that was a very Stoic thing that I read as [inaudible 00:43:10] this conversation. What do the Stoics say about changing our desires, or moderating our desires, so it lines up with a virtue?

Donald Robertson: Well, let me digress for a second, actually, and just say something about Paul. I think it helps to put Stoicism in a historical context, to say that you can view Stoicism as one of the main precursors of early Christian ethics. One modern scholar actually called St. Paul a crypto-Stoic, a secret Stoic. There are obvious Stoic influences on Christianity, particularly the idea of the brotherhood of man. So, that very much was a concept that was associated with Stoicism. You can see that running all the way through the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, more associated with Stoicism than most other philosophical schools.

But St. Paul, just as a little bit of trivia, a little aside, not a lot of people know this, but in the Acts of the Apostles, we’re told that St. Paul went to a place in Athens called the Areopagus, and that he actually spoke to a group of Stoic and Epicurean philosophers, and he quoted a poem from one of the early Stoics, a guy called Aratus, approvingly to them. So, he definitely knew Stoics and talked to them about philosophy and stuff. He was talking to them, actually, about Stoic pantheism, that’s what the poem was about that he was quoting. So, that kind of aside, a little bit of history that might be of interest to some people.

What do the Stoics say about desires? Sometimes Stoic therapy is called the therapy of desire, by modern scholars, because desire is really central. Desire is one of the passions for Stoicism. The Greek term for passion encompasses both what we would call desires and emotions. The Stoics think our desires can become excessive, irrational, unhealthy, and they can lead us into vice, so we have to be careful to take a step back from them. The key for Stoics is awareness. It’s about spotting our desires at the earliest possible stage, so that we can nip them in the bud if it turns that they are unhealthy or destructive.

The way to deal with that is to think about the consequences more carefully, more patiently, and more vividly. So, the Stoics are always telling us to kind of picture in our mind’s eye where our desires are going to lead us in the longer term, and that’s something that we do in modern therapy as well, similar to what we call functional analysis. Getting clients to think about what would happen if you indulged certain desires over the long term, and then what would happen if you exercised more discipline, is almost like a fork in the road, and two paths that diverge further and further over time.

Another thing the Stoics would do would be to role model wise and good people, just think about the people you most admire in life, and how they would deal with similar desires, because most of us tend to admire people that exercise self-discipline, although we’re more lax in exercising it ourselves. So, one of the main themes of Stoicism is to train ourselves to become more like the sort of people that we admire in life, because the Stoics think of it as being kind of hypocrisy, in a way, to admire self-discipline in people but not to be self-disciplined ourselves, and they want us just to be more consistent in our morality, more consistent in our thinking, by being more like the sort of people that we typically praise and admire. So, modeling other people is another way of coping with desire in Stoicism.

Brett McKay: What about anxiety and worry? That seems like a topic that Marcus wrote a lot about in his Meditations.

Donald Robertson: Yeah, I mean, the Stoics are very concerned with fear, and anxiety, and worry, and so some of the things that they would talk about would be, for example, what we mentioned earlier, decatastrophizing. So, in modern therapy, that’s one of the main techniques that we use today. Worry is absolutely a particular style of thinking, as it’s defined in modern psychology. We call it what-if thinking. What if this just ends in a disaster? What if I can’t cope? So, what-if thinking is very deeply associated with catastrophizing, or kind of exaggerating how bad things are going to be, and underestimating our ability to cope. The Stoics want us to question that, to take a step back from it and re-describe things in more objective and down to earth language.

They also want us to notice when we’re beginning to worry, and postpone it. So, Epictetus says take a step back, withhold judgment for a while, until you’ve calmed down and you can think through things more clearly at your leisure. We call that worry postponement, today. It’s one of the most effective techniques in the cognitive therapy of worry and anxiety, so learning to spot when we’re starting to worry and catastrophize, and taking a kind of time out from it and saying, “Wait a minute, I’m going to come back and think about this a few hours from now, or later in the evening when I’ve calmed down a little bit, and I’m able to think about it more clearly and to problem solve in a more rational way.”

Brett McKay: Another tactic that Stoics use, or sort of a meditation, is to look at the big picture, or say that this is the way things are, it’s fate or nature, and getting upset about it doesn’t change it, so don’t get upset about it.

Donald Robertson: Yeah, and when we look at the bigger picture, as I mentioned earlier, it tends to make things seem smaller in scope, and also more transient, like it’s just a moment in our life, “This too shall pass.” So, it’s linked in with this idea of the impermanence or the transience of things.

Just as an aside, in modern therapy, we notice, when people are worrying and catastrophizing, it’s almost a kind of interesting puzzle, the way that thinking works in some situations. So, you know if you’re thinking about losing your job, for instance, or the end of a relationship, that’s a sequence of events, right? It’s like a little movie clip in your mind, and you could choose to focus on any particular part of it, in the chronological sequence, but when people are worrying, they tend to obviously focus on the scariest part of it, the most upsetting part, and kind of stop there, and go round and round that bit.

We find, in therapy, that very simply, if we sometimes say to people, “Well, what would probably happen next?” And then get them to kind of answer that question, and then keep asking it, and then what would probably happen? And then what would probably happen? Well, if I broke up with my girlfriend, it would be just catastrophic, it’d be the end of the world. Well, what would probably happen next? Well, I’d probably feel really depressed and I would kind of stay at home and I wouldn’t go out. And then what would probably happen after that? Well, I guess I would start to think about socializing again, and meeting other people. And then what would probably happen next? Well, I guess I’d probably meet another girl and form another relationship, and so on.

So, when we get people to move forward in a kind of patient, systematic manner, it tends to damp down the initial anxiety, and they view things in a more balanced way, and also they start to think more about ways of coping. Whereas when people are worrying, they tend to just tell themselves that they can’t cope.

The Stoic technique of thinking of things in terms of a wider context, I think serves a similar purpose. It forces us to realize that the perceived catastrophes that happen to us are temporary, and that we have to move on from them, and that seems less overwhelming.

Brett McKay: This idea of Stoic acceptance, is it fatalism? Did the Stoics say, well, that’s just the way things are, there’s nothing you can do about it, or was their fatalism different from that passive fatalism?

Donald Robertson: Yeah, the idea of the Stoic as a kind of passive doormat that just sits on his hands and stays at home, the stay at home Stoic, right? Well, that’s a caricature of Stoicism. One of the reasons that I wrote How to Think Like a Roman Emperor is that I find when I’ve been teaching Stoicism, I mean, I’ve been teaching Stoicism and writing about it for, I think it’s probably just over 20 years now, and time and time again, I’ve found that these kind of misconceptions of Stoicism come up, like it’s about being unemotional, it’s about being kind of passive and inert.

You can argue with people about that by referring to the texts of the philosophical doctrines, but actually, the easiest way to dispute it is just to point at a Stoic, like Marcus Aurelius, or Cato, or Zeno, and say, “Do these guys seem like they were passive doormats? Obviously they weren’t.”

Marcus Aurelius was a workaholic, if anything. He put himself at the front line in commanding the largest army ever assembled on a Roman frontier. We think the Roman legions along the Danube during the Marcomannic Wars numbered maybe 140,000 men in total, the legions and the auxiliary units combined. That’s a huge army, and he’d never served in the military before, but even as a sickly man with many health problems, in his 40s, he rode out from Rome, put on his general’s uniform, went to a foreign country for the first time, to modern day Austria, and took command of this huge army, staking everything on it. So, he wasn’t this kind of fatalistic, passive, stay at home type, quite the opposite. Stoics were committed to action in the service of wisdom and justice.

The thing about Stoicism is that it teaches us how to reconcile a commitment to determined action, in the service of our fundamental values and principles, with emotional acceptance, so that we don’t become upset if we encounter setbacks, or we’re thwarted along the way, because the Stoics think that the most important thing is to have the intention to do good in the world, while simultaneously accepting the fact that we might not succeed, or that we might encounter resistance or setbacks along the way, and not to kind of get upset or feel overwhelmed if that happens.

Now, that’s explained famously by Cicero. Cicero wasn’t a Stoic, he was a follower of the Academic school of philosophy that was founded by Plato, but Cicero, a famous Roman orator who lived centuries earlier than Marcus, was a very educated man, and he’d studied Stoicism at Athens. He tells us that the Stoics explain this as being like a man throwing a spear, or an archer. He focuses on throwing the spear at the target to the best of his ability. Whether he actually hits the target or not is in the hands of fate. Once the spear has flown, if he’s throwing it at a wild boar, for example, it might dart in the opposite direction and he might miss it. But his only goal is to throw the spear in the most skillful way that he possibly can, and then to be relatively indifferent to whether he actually hits the target or not, simply to do the best insofar as that’s within his power. But in order to try his best, he has to have a target to aim at.

That’s how the Stoics view the goal of benefiting humanity. They have to have that goal in order to aim at something constructive and meaningful in life, to have a sense of purpose in life, but they mustn’t demand success. They have to be relatively accepting of the fact that they might fail or encounter setbacks along the way.

Brett McKay: That’s a tough rope to walk, because there’s like a tension there, that I think could be really-

Donald Robertson: It’s a balancing act, right?

Brett McKay: Right. Because you have to do your best, but not be attached to the results, but the results are often what spurs you or motivates you to do your best, but you have to take a step back and not do that, and that can be tricky.

Donald Robertson: Those are the preferred indifferents in Stoicism, which is kind of misleading language. The Stoics also say that those things have value, or axia, in Greek. So, those are things that we value, that we want to achieve, but as soon as we fail to achieve them, the Stoics say they become completely indifferent to us. It’s like water off a duck’s back, as it were, so the Stoics should just kind of shrug that off and move on to the next thing.

But nevertheless, while we’re aiming for them, they do have a certain type of limited importance or value, and we have to assign that value to things in order to motivate ourselves and to have something to focus on. But the value that we assign to hitting the target should never be so much that it would distress us if we miss. We shouldn’t place so much value on it that we throw a tantrum or get upset if things don’t go as we would’ve desired. And we should never place more value on obtaining those externals than we place on our own strength of character, on our own wisdom and virtue. Wisdom and virtue always trumps the value that we place on externals. That’s like the Stoics basically saying we should never sell out for wealth or reputation or whatever. We should never be willing to sacrifice our own character and integrity, no matter how much is at stake externally.

Brett McKay: How does a Stoic deal with, say, trying to extinguish an injustice in the world? The Stoics were about justice, but in the process of, say, in fighting some injustice, they might have setbacks. How would the Stoics… Do they say just don’t get upset, just keep trying? Would that be their…

Donald Robertson: Well, as Ryan Holiday says, he paraphrases one of the passages in the Meditations for his book, The Obstacle is the Way, and that’s exactly what the Stoics mean. So, when we encounter an obstacle, it now becomes a new opportunity for us to exercise virtue. We flow around it like water, is kind of how the Stoics envisage it, or as Marcus says, “The mind of the wise man is like a blazing fire,” and obstacles are just like more fuel, more wood that’s thrown in the fire, and it consumes them.

So, for the Stoic, if he encounters a setback when he’s trying to act in the service of justice, he needs to just accept the reality of it, accept his situation, and then he decides what would constitute wisdom and justice in responding to the new situation. So, he just adapts and then tries to act with virtue and integrity in the face of the new situation that he’s now encountering.

Brett McKay: Well Donald, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book?

Donald Robertson: Well, if they want to find more about the stuff that I do, my website is just my name, it’s donaldrobertson.name, not dot com. I have a lot of free courses and downloads as well that people can do, and that’s just on my e-learning site, which is just the sub-domain learn, so it’s learn.donaldrobertson.name. The main books that I’ve written… I’ve written six books, but the ones on Stoicism are How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, the one we’ve been talking about, The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, and also a teach yourself book called Stoicism and the Art of Happiness. They can find these books on Amazon or any online bookstore. Also, the more academic book that I wrote for therapists and philosophers is called The Philosophy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and that goes more deeply into the relationship with psychotherapy, and the history of Stoicism and psychotherapy.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Donald Robertson, thanks so much for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Donald Robertson: Thanks, Brett. It’s been a pleasure speaking to you.

Brett McKay: My guest here is Donald Robertson. He’s the author of the book How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, it’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about his work at his website, donaldrobertson.name, or also, check out our show notes at aom.is/marcus, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archives as well as thousands of articles written over the years, some about Stoicism, we even have articles about how to be a better husband, better father, fitness, you name it we’ve got it.

If you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the Art of Manliness Podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code MANLINESS to get a free month trial of Stitcher Premium. Once you’re signed up, download the iOS or Android app for Stitcher, and then you start enjoying ad-free episodes of the Art of Manliness Podcast.

If you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot, and if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing this show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it.

As always, thank you for the continued support, and until next time, this is Brett McKay reminding you, not only listen to the AOM Podcast but put what you’ve heard into action.