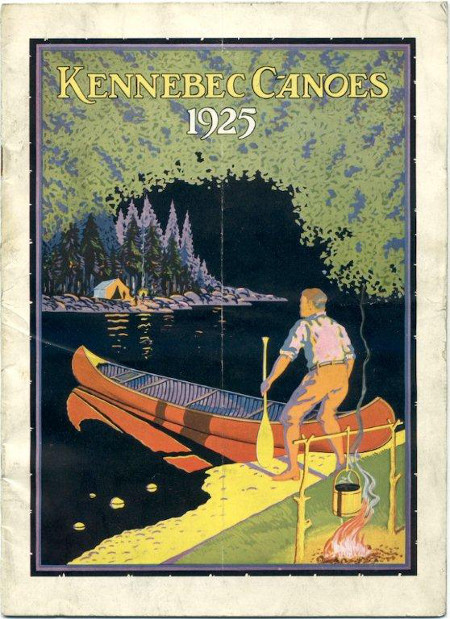

“Vacation Time”

From The Book of Camping and Woodcraft, 1918

By Horace Kephart

To many a city man there comes a time when the great town wearies him. He hates its sights and smells and clangor. Every duty is a task and every caller is a bore. There come visions of green fields and far-rolling hills, of tall forests and cool, swift flowing streams. He yearns for the thrill of the chase, for the keen-eyed silent stalking; or, rod in hand, he would seek that mysterious pool where the father of all trout lurks for his lure.

To be free, unbeholden, irresponsible for the nonce! Free to go or come at one’s own sweet will, to tarry where he lists, to do this, or do that, or do nothing, as the humor veers; and for the hours,

It shall be what o’clock I say it is!

Thus basking and sporting in the great clean out-of-doors, one could, for the blessed interval,

Forget six counties overhung with smoke,

Forget the snorting steam and piston-stroke,

Forget the spreading of the hideous town.

This instinct for a free life in the open is as natural and wholesome as the gratification of hunger and thirst and love. It is Nature’s recall to the simple mode of existence that she intended us for.

Our modern life in cities is an abrupt and violent change from what the race has been bred to these many thousands of years. We come from a line of forebears who, back to a far-distant past, were hunters in the forest, herdsmen on the plains, shepherds in the hills, tillers of the soil, or fishermen or sailors at sea; and however adaptive the human mind may be, these human bodies of ours still stubbornly insist on obeying the same laws that Father Adam’s did.

There are soothsayers who forecast that, in the course of evolution, we shall conform to what are now abnormal and mischievous conditions; that man is the most adaptive of all creatures, accommodating himself to greater extremes of temperature and so forth than any other of the higher animals; that moreover he is constantly inventing machines and processes to better his condition, so that we may reasonably expect him to make even the crowded city a wholesome place of residence, though people dwell tier above tier, and our old-fashioned domestic life be quite out of the question.

It may be so. We can fix no bounds to Nature’s conforming power . . . Some of our own people seem to get no satisfaction out of anything but chasing after dollars without let-up from year to year, save when they are asleep, or in church, or both. We recall a certain rich man who boasted that in the eighty-eight years of his career he had not once taken a vacation or wanted one. Naturally his way was the right way, and he proceeded to show it. “What right,” asked he, “has a clerk to demand or expect pay for two weeks’ time for which he renders no equivalent? Is it not absurd to suppose that a man who can work eleven and a half months cannot as well work the whole year? The doctors may recommend a change of air when he’s sick; but why be sick? Sickness is an irreparable loss of time.” I am not misquoting this very rich man: his signed pronouncement lies before me — the sorriest thing that ever I saw in print.

Seriously, is it good for men and women and children to swarm together in cities and stay there, keep staying there, till their instincts are so far perverted that they lose all taste for their natural element, the wide world out-of-doors? In any case, although evolution be a very great and good law, yet is it not a trifle slow? How about you and me? Can we wait a few thousand years for fulfillment of the wise men’s prophecy?

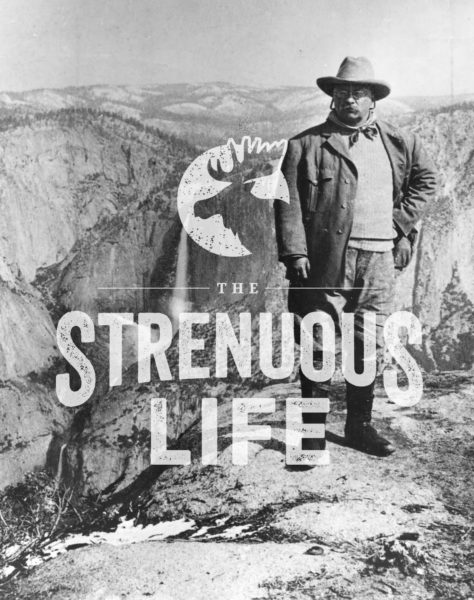

Granting, then, that one deserves relief now and then from the hurry and worry that would age him before his prime, why not go in for a complete change while you are about it? Why not exorcise the devil of business and everything that suggests it? The best vacation an over-civilized man can have is to go where he can hunt, capture, and cook his own meat, erect his own shelter, do his own chores, and so, in some measure, pick up again those lost arts of wildcraft that were our heritage through ages past, but of which not one modern man in a hundred knows anything at all. In cities our tasks are so highly specialized, and so many things are done for us by other specialists, that we tend to become a one-handed and one-idead race. The self-dependent life of the wilderness nomad brings bodily habits and mental processes back to normal, by exercise of muscles and lobes that otherwise might atrophy from want of use.

If one would realize in its perfection his dream of peace and freedom from every worldly care, let him keep away from summer resorts and even from farms; let him camp out; and let it be the real thing. There are “camps” so-called that are not camps at all. A rustic cottage furnished with tables and chairs and beds brought from town, with rugs on the floor and pictures on the walls, with a stove in the kitchen and crockery in the pantry, an ice-house hard by, and daily delivery of groceries, farm products, and mails, may be a pleasant place in which to spend the summer with one’s family and friends; but it is not a camp. Neither is a wilderness clubhouse, built on a game preserve, looked after by a caretaker, and supplied during the season with servants and the appurtenances of a good hotel.

A camp proper is a nomad’s biding-place. He may occupy it for a season, or only for a single night, according as the site and its surroundings please or do not please the wanderer’s whim. If the fish do not bite, or the game has moved away, or unpleasant neighbors should intrude, or if anything else goes wrong, it is but an hour’s work for him to pull up stakes and be off, seeking that particularly good place which generally lies beyond the horizon’s rim.

Your thoroughbred camper likes not the attentions of a landlord, nor will he suffer himself to be rooted to the soil by cares of ownership or lease. It is not possession of the land, but of the landscape, that he enjoys; and as for that, all the wild parts of the earth are his, by a title that carries with it no obligation but that he shall not desecrate nor lay them waste.

Houses, to such a one, in summer, are little better than cages; fences and walls are his abomination; plowed fields are only so many patches of torn and tormented earth. The sleek comeliness of pastures is too prim and artificial, domestic cattle have a meek and ignoble bearing, fields of grain are monotonous to his eyes, which turn for relief to some abandoned old-field, overgrown with thicket, that still harbors some of the shy children of the wild. It is not the clearing but the unfenced wilderness that is the camper’s real home. He is brother to that good old friend of mine who, in gentle satire of our formal gardens and close-cropped lawns, was wont to say, “I love the unimproved works of God.” He likes to wander in the forest tasting the raw sweets and pungencies that uncloyed palates craved in the childhood of our race. To him

The shelter of a rock

Is sweeter than the roofs of all the world.

The charm of nomadic life is its freedom from care, its unrestrained liberty of action, and the proud — self-reliance of one who is absolutely his own master, free to follow his bent in his own way, and who cheerfully in turn, suffers the penalties that Nature visits upon him for every slip of mind or bungling of his hand. Carrying with him, as he does, in a few small bundles, all that he needs to provide food and shelter in any land, habited or uninhabited, the camper is lord of himself and of his surroundings.

Free is the bird in the air,

And the fish where the river flows;

Free is the deer in the wood,

And the gipsy wherever he goes.

Hurrah!

And the gipsy wherever he goes.

There is a dash of the gipsy in every one of who is worth his salt.

Tags: Manvotionals