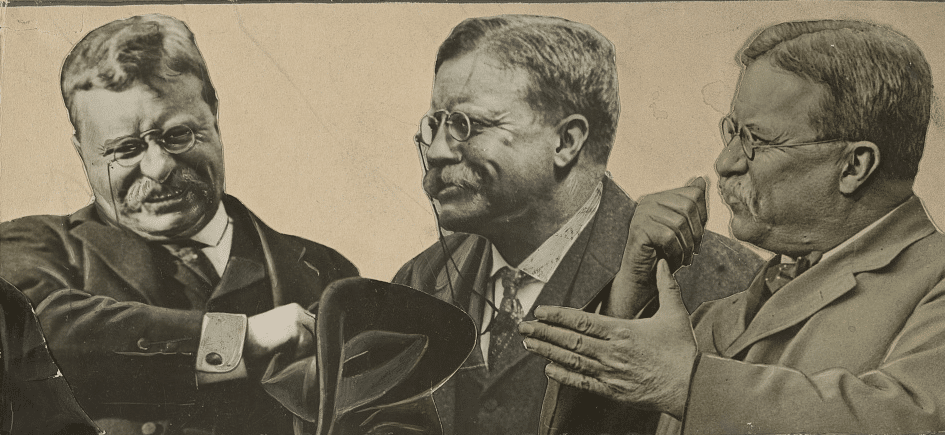

“The Powers of a Strenuous President”

From The American Magazine, 1908

By “K”

I have known Mr. Roosevelt personally for ten years—not intimately—but something more than casually … I have heard the President explained biographically, historically and politically … And I have not been satisfied.

A Golden Key to Unlock Roosevelt

I have not been satisfied even with my own understanding of him until I read a recent article by Professor James of Harvard on “The Powers of Men.” It is indeed one thing to know a man, quite another to explain him. If I had not come across Mr. James’ psychological key (a key of gold) I should certainly never have attempted to unlock, in public at least, the character of Theodore Roosevelt as I see it. And I am doing it now for my own satisfaction, recognizing the privilege of other free-born citizens to entertain any other view of him that may satisfy them.

Mr. James’ thesis, as I understand it, is that few men use the vast stores of hidden energies which they possess, that most of us suffer from the “habit of inferiority to our full selves.” He points out the extraordinary accomplishments of men who have learned the art of “energizing,” as he calls it, to the limit of their deepest capacities …

These remarks set me to thinking. It struck me at once that Roosevelt, more than any man I ever knew, is “energizing” to the extent of his capacities. His command of his capacities is even more remarkable than the capacities themselves.

Roosevelt’s Familiarity

In no one of his varied faculties, except in this faculty of “energizing,” is Roosevelt a remarkable man. It is common to meet men of far less fame than Roosevelt who give one a peculiar “feeling of greatness,” of some transcendent quality of genius which is above and beyond the reach of mere human capacity. In talking with many people who have met Roosevelt for the first time I have been impressed by their comments upon his “familiarity,” his “commonness.” He is “just like one of us.”

I recall distinctly the first time I met Roosevelt. It was at Oyster Bay—before he was elected Governor of New York. It was a warm afternoon and he had been bathing in the bay, and came up dripping and puffing, with his hair streaming sea water. We shook hands and sat down together on a bench near the bath house and had a good talk. I have tried (in vain) to imagine such an experience with Gladstone—or Elihu Root! I have understood that a man who meets J. P. Morgan for the first time slowly shrivels up and quietly disappears through a crack in the floor provided for that purpose.

Not so Roosevelt. Roosevelt is familiar. He does not act familiar, he is familiar; he is “just like one of us.” He is “Teddy” to half the nation. Many of those who meet him familiarly speak of him as “T. R.” He talks about the things we talk about, not as a political artifice, but because he thinks them—and can’t help it. As I have heard him say more than once:

“I am no genius. The things I talk about are not new; they are the plain, familiar principles of right and wrong.”

As every one knows, he has emphasized the common qualities and virtues in his speeches and messages until he has been accused of “uttering homilies,” preaching sermons and moralizing. To the intellectual and subtile his words have been a burden, like the grasshopper of the Good Book. He has not pleased them and he never will: for he is not subtile, but common.

I have found innumerable references in his books and papers to the value of qualities of commonness. Speaking as police commissioner of New York City of the administration of the police force, he said:

“We found that there was no need of genius, nor, indeed, of any unusual qualities. What was needed was the exercise of the plain, ordinary virtues, of a rather commonplace type, which all good citizens should be expected to possess. Common sense, common honesty, courage, energy, resolution, readiness to learn, and desire to lie as pleasant as compatible with the strict performance of duty—these were the qualities most called for.”

And those were Roosevelt’s qualities. The marvelous thing in his career is the way in which he has used those qualities—in every possible direction. His versatility amazes one: his energy is appalling: and yet it is only commonness energized to the Nth degree.

As an Author

As an author, for example, his production at fifty years old exceeds in volume the life work of many great writers. I haven’t counted the words but I should be surprised if he had not written more than Shakespeare. And yet one would hesitate to say that he has produced any real literature; he has never touched (and cannot touch) the sublime simplicity of Lincoln’s Gettysburg address or Washington’s farewell to the country. He has never yet suffered a book.

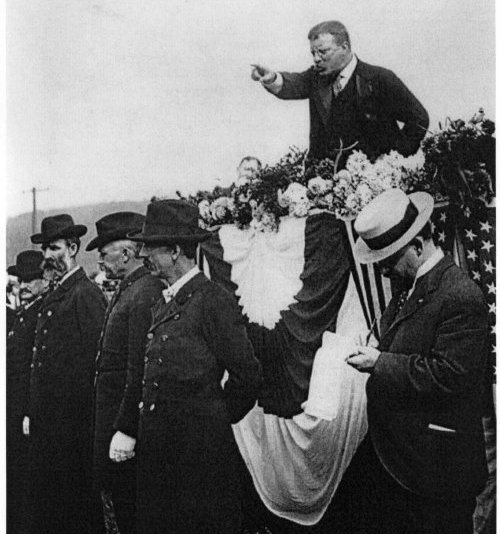

He was a soldier and a brave one, but no one certainly would call him a military genius even within the limited scope of his activities. A soldier is great in proportion to his ability to use other men, he himself remaining in the background, his victories are intellectual; but Roosevelt succeeded by sheer hustle and muscle; he, personally, got there first.

He has been a reformer and accomplished very great good, though he never burned with the fire of a Martin Luther or a Garrison or Phillips. Unlike the great reformers, he has always been with the crowd, never against it. For those who really oppose the multitude, as Socrates says (in the Apology of Plato), cannot hold high offices nor save their lives.

He has been a politician, but not a genius in the art like Blaine, for he has been restrained (to his own advantage) by another common quality, a sort of literal honesty.

Why Roosevelt is not a Good Shot

At Harvard he was a boxer, a wrestler and a runner, but he never took any championships; he has shot big game, but has never been a first-class shot. He says himself in one of his Western books:

“I myself am not and never will be more than an ordinary shot, for my eyes are bad and my hand not over steady; yet I have killed every kind of game to be found on the Plains, partly because I have hunted very perseveringly, and partly because by practice I have learned to shoot about as well at a wild animal as at a target.”

Now, that is Roosevelt—in his own words. An ordinary shot, yet he has killed every kind of game by perseverance and practice.

In other words, he has succeeded by his extraordinary capacity for energizing—for using every ounce of every capacity he possesses: by strenuous self-discipline, control and development. It is “the strenuous life” he glorifies, for it has made him what he is.

A Delicate Boy

As a child he was a weakling, pale and delicate, so that he was tutored at home and not allowed to join in the rough play of other boys. He was even slow to learn. But as I heard him once say, he made up his mind that if he ever amounted to anything he must acquire physical vigor. So he set about developing himself; he rode and swam and ran, lived an active outdoor life. He learned in early years to submit himself to the severest discipline, and that habit, gathering power, has been with him all through life. No man today in this country works harder week in and week out than the President. In other words, Roosevelt has learned to “energize,” in every direction where he possesses any capacity whatsoever. If he had found within him even a spark of ability as an artist we should have had him (like Emperor William, who is another energizer) painting pictures—not necessarily good ones, but pictures.

President Never Erratic

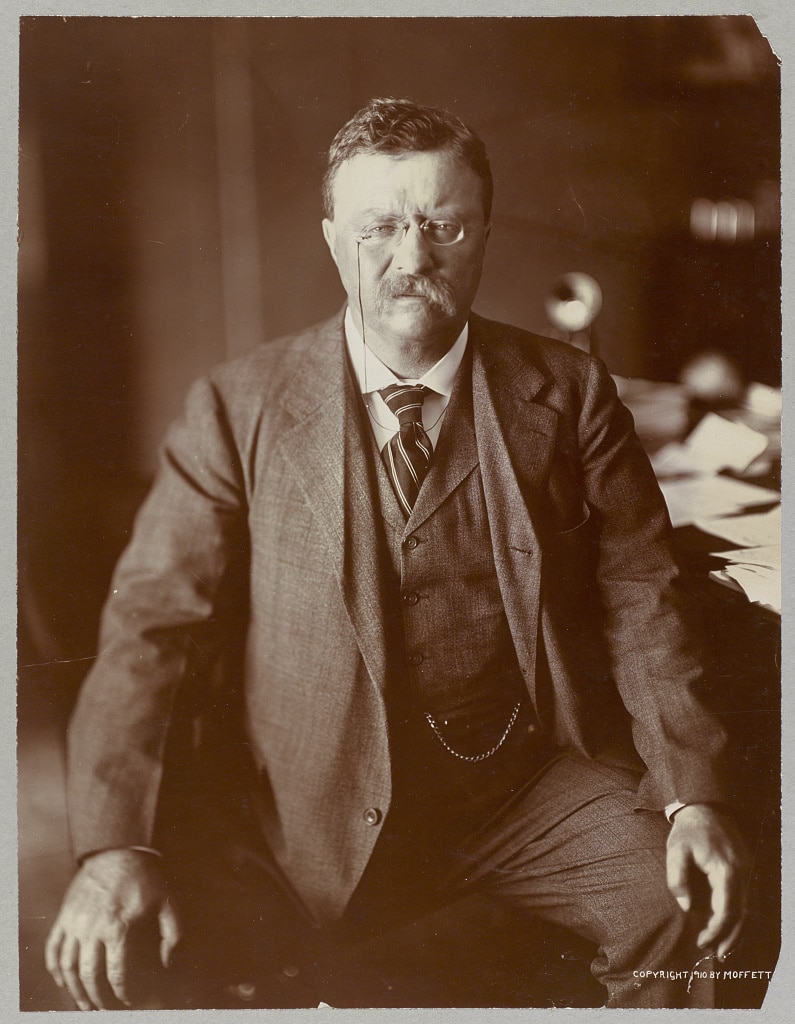

People sometimes call the President “erratic” and “eccentric” (they mean “impulsive”); but I could never see that he was either erratic or eccentric. He couldn’t be. He is profoundly normal, physically and mentally (which genius is not). His habits and life are temperate: he is abstemious in eating, drinking, sleeping; for that is part of the care which he gives his energizing machine. His family life is normal, and he exhorts all America to a similar normality. He exercises every day with the regularity of clockwork, tennis on Wednesday, a tramp on Thursday, horseback riding Friday, boxing Saturday, or to that effect. It may seem violent exercise to some: to Roosevelt it is the normal expression of his highly energized daily life. His religion is normal and expressed normally. He has the normal capacity for friendships.

Contrary to the belief of some people with whom I have talked, the President is the very incarnation of order and regularity in his work. That is part of his system of energizing. Every morning Secretary Loeb places a typewritten list of his engagements for the day on his desk, sometimes reduced to five-minute intervals. And no railroad engineer runs more sharply upon his schedule than he. His watch comes out of his pocket, he cuts off an interview, or signs a paper, and turns instantly, according to his timetable, to the next engagement. If there is an interval anywhere left over he chinks in the time by reading a paragraph of history from the book that lies always ready at his elbow or by writing two or three sentences in an article on Irish folklore, or bear hunting.

How He Schedules His Engagements

Thus he never stops running, even while he stokes and fires; the throttle is always open; the engine is always under a full head of steam. I have seen schedules of his engagements which showed that he was constantly occupied from nine o’clock in the morning, when he takes his regular walk in the White House Park with Mrs. Roosevelt, until midnight, with guests at both luncheon and dinner. And when he goes to bed he is able to disabuse his mind instantly of every care and worry and go straight to sleep, and he sleeps with perfect normality and on schedule time.

I have been thinking back over Roosevelt’s career in the White House and I cannot now remember to have heard that he was ever ill or even indisposed as other men sometimes are. Like any good engineer, he keeps his machinery in such excellent condition that he never has a breakdown.

Thus we have the spectacle of a man of ordinary abilities who has succeeded through the simple device of self-control and self-discipline, of using every power he possesses to its utmost limit—a dazzling, even appalling, spectacle of a human engine driven at full speed—the signals all properly set beforehand (and if they aren’t, never mind!).

Secret of Roosevelt’s Greatness

Now this power of energizing as displayed by Roosevelt is certainly a very rare and great one: it represents a supreme development of the human will. No man of our generation has used himself more effectively than Roosevelt. And that is wholly to his credit; as John Burroughs says somewhere in one of his essays: “What nature does with a man—that is no credit to him; but what he does with nature.” The story of Roosevelt will always be an inspiration to struggling, limited youth: for he is the very pattern, in a new sense, of a self-made man. By perseverance and practice (those virtues of the primer) he has killed all kinds of game and sits in the White House.

Tags: Manvotionals