I’m in the midst of a project to read a biography of every president. With most of the men, there’s a pretty clear sense that they were glad to give up the office after their term. It’s an exhausting job in which the Oval Office occupant is relentlessly attacked by his opponents, and sometimes by his own party. Even the great acts of the presidency — the Louisiana Purchase, the Emancipation Proclamation, the New Deal, just to name a few — were reviled by the partisans of the era. It’s a tough job.

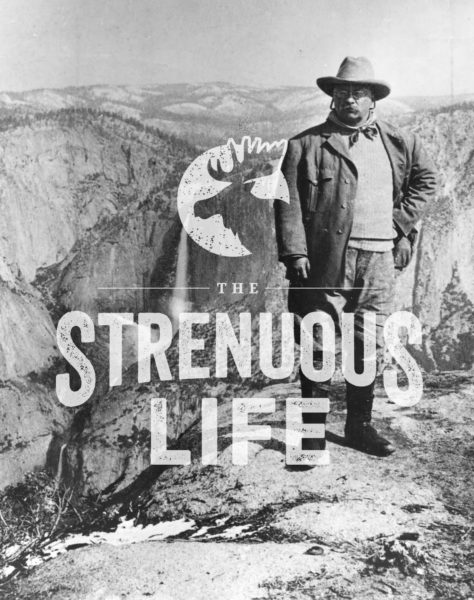

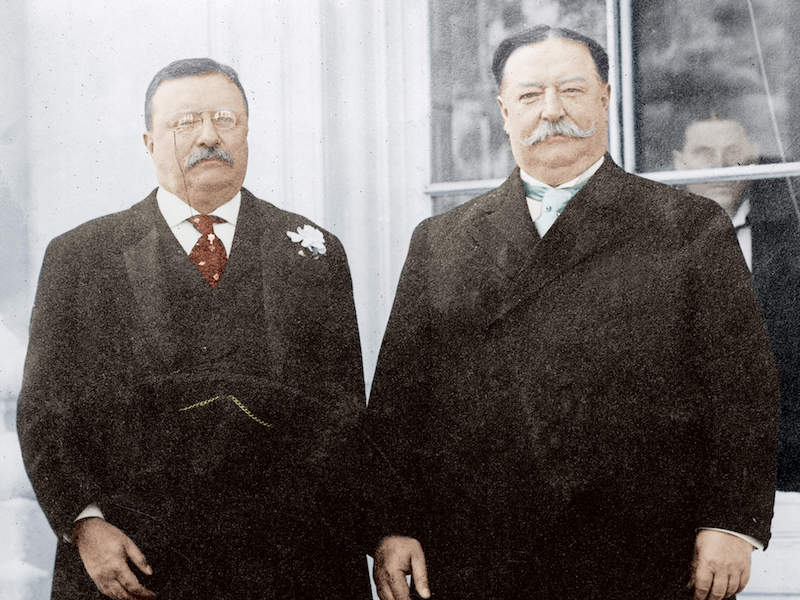

But Theodore Roosevelt loved it. He reveled in just about every aspect of the job and found his White House years to be the most fulfilling of his life. Rather than seeming haggard and worn out at the end of his 7.5 years in office, as all presidents before and since appear to be, he was still brimming with energy and enthusiasm for politics. Like no other man who’s held the office, Roosevelt was perfectly suited for the job of being POTUS.

He could have sought a third term, but made a promise after the 1904 election to give someone else a shot at the top job. Where other politicians have reneged on similar promises, Roosevelt was unquestionably a man of his word. Of course it helped that he had a protege to take up the mantle after he was gone; he had long been preparing William Howard Taft to follow in his footsteps.

So on March 4, 1909, Theodore stood to the side while Taft took the oath of office. He would have a very different experience leading the nation in what ended up being a prime example of someone being perfectly unsuited for their job.

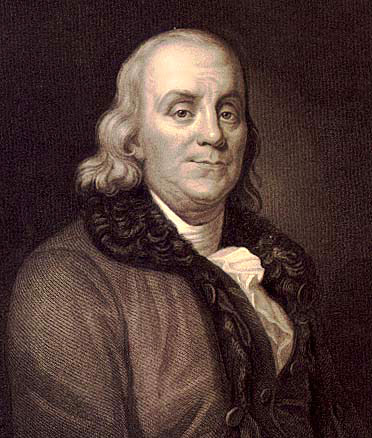

William Howard Taft as President of the United States.

If you know anything about Taft, “Will” to his friends and family, it’s the bathtub story. The nation’s largest president once got stuck in a White House bathtub — or so you’ve heard. The reality is that Taft knew he was a big guy, eventually tipping the scales at well over 300 pounds, and had extra large tubs installed once he took residence. So forget that story and instead learn a few things about the real Taft — the affable guy who Roosevelt dearly loved and relied on.

Even as a child, William Taft was a lovable creature. “It was very hard for anybody to be near him without loving him,” said younger brother Horace. He was always popular, but less in a charismatic way than in an incredibly genial, huggable way. Will disliked debate and criticism, loved deep thought, and was slow, but remarkably deliberate, in his actions. Taft pursued the law, which seemed to be the perfect career match for his temperament (courtrooms are less theatrical than they’re often portrayed on TV, and that was especially true a century back).

In his late twenties, after being awarded his first local judgeship, Taft set some high ambitions for his life. He wanted to be a Supreme Court justice — Chief Justice to be more specific. His natural inclinations towards genial relationships, measured decisions, and an intellectual life lined up especially well with being a judge. For him, a day on the bench using his intellect followed by a quiet evening at home in his library was far preferred to knocking elbows with other politicians and taking on party bosses in the court of public opinion.

William Taft did the job as well as any judge could, eventually working his way up to a federal judgeship. In Bully Pulpit, Doris Kearns Goodwin writes that “No one on the circuit was more widely respected or better loved than Taft.” He was a content man and well on his way to earning a Supreme Court nomination.

But Will married an intensely ambitious woman, Nellie, who yearned for the White House. Sure, the Supreme Court would be nice, but it wasn’t the most prestigious or glorified position — it was not the very highest echelon of American achievement. There was only one job which could satisfy that goal: President of the United States.

Taft dearly loved his wife and had a clear weakness when it came to being overly influenced by those around him, so when President William McKinley offered Taft the governorship of the Philippines in 1901, he took it. It would be a better stepping stone to political advancement than continuing on the bench.

But McKinley was assassinated shortly afterwards. Theodore Roosevelt, a good friend of Will’s, ascended to the presidency, knowing that Taft’s ultimate aim was the Supreme Court. In 1902, a spot on that highest court opened up and Roosevelt floated the job to Taft. It was his for the taking.

The big man turned it down, claiming that his current position as governor of the Philippines wasn’t done yet. There can be no doubt of Nellie’s influence in that decision to hold out for something else, though. Throughout his career, she consistently pushed him to seek an ever higher office. So when President Roosevelt wanted Taft as his Secretary of War, he said yes to that position, ascending further up the political hierarchy, and becoming, in Roosevelt’s own words, “my counsellor and adviser in all the great questions that come up.”

Beyond Nellie’s influence, Roosevelt also eventually encouraged Will to follow in his footsteps to the White House and serve as caretaker to his legacy. Theodore did say, however, that “the equation of the man himself” must be the primary factor in deciding what to do with one’s life.

Regardless of that good advice, a yielding Taft didn’t want to let anybody down, and, riding on Roosevelt’s wave of popularity, won the presidential election of 1908. Even though Nellie was “finally entirely in her element,” Taft hated the job from the start. “Within hours of his election triumph,” Goodwin writes, he “was already anguished that his nature was ill-suited to his new role.”

It was a middling four years in office for William Howard Taft. Sadly, Nellie suffered a devastating stroke just 10 weeks into the term, which handicapped her for much of her husband’s presidency. Without his beloved wife by his side, Taft was even more despondent about the job. Roosevelt, disappointed by his friend’s performance as POTUS (saying of him, “he means well, but he means well feebly”) rose from the ashes as a third-party candidate, coming in second place to Woodrow Wilson. Taft came in third and retired back to his home in Ohio, happy to put behind him the most miserable years of his life. Just about the only thing that came out of it, in popular memory, was that embarrassing bathtub rumor.

In 1921, Will finally got his chance to fulfill his dream when Chief Justice Edward White died. Fellow Republican and Ohioan Warren Harding awarded Taft the job, knowing it had been his lifelong ambition. On the day he was sworn in, Will said, “This is the greatest day of my life.” It wasn’t the most prestigious job in the land, but it was the one most suited to William Howard Taft. He relished every minute of it until his death in 1930.

William Howard Taft as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Notice how content he looks compared to the portrait above.

In my reading of Taft’s life and career, I just felt sad for the poor fella. He could have had twenty extra years doing what he loved, but was pushed into something he knew he wouldn’t thrive at nor enjoy. Sure, you can lay some blame on Nellie and Theodore for pushing the guy too hard, but there wasn’t anything malicious in their intent. The relationships Taft had with both of them were mutually and authentically loving and caring.

Rather, this is a classic example of someone playing the “should” game at the very highest levels of leadership. I can imagine Taft saying, “I love Theodore and want to uphold his legacy; I should run for president,” as well as, “My wife is my rock and I want her to be happy; I should run for president.” The visceral pull of status likely played a role too; when he saw the brass ring dangling in front of him, he felt he should grab it — that he was supposed to grab it. In so doing, he put off his own happiness, his own fulfillment, for decades. Goodwin conveys this same sentiment:

Always plagued by procrastination and insecurity, Taft struggled to turn [his] intuitive emotional intelligence inward to access his own desires and use that knowledge to steer his life and career accordingly.

Can you relate?

The obvious corollary is with your career. Is social media/family/friends/culture egging you into pursuing a life you don’t really want?

Entrepreneurship certainly appears alluring online, but perhaps you actually enjoy the less stressful, check-in/check-out nature of your 9-5 job.

Going to college and working in an office might seem like the proper path to take, but maybe you’d really rather go to a technical school and learn a blue collar trade.

You might feel like you need to keep moving up the rungs of your company, but is shifting away from doing fieldwork to assuming a more managerial position really suited to your talents and desires?

Beyond just the professional realm of life, though, a man should pursue the things he truly likes elsewhere, too: hobbies, books (and other content/media), recreation and fitness, etc.

Just because Instagram goes crazy for craft beer doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy the cheap stuff. Just because your book club is into Greek classics doesn’t mean you can’t read all the Jack Reacher novels your heart desires. Just because every other millennial worships at the altar of international adventure travel doesn’t mean you can’t be a homebody who enjoys regional road trips as much as anything else.

Don’t be pushed into pursuing the career or hobby or idea that someone or something else has thrust upon you as the highest ideal.

Rather than seeking out what looks great, or seems like it should be fulfilling, spend time getting to know your own temperament and your own likes. Find ways to pursue the Good that align with your native talents and intrinsic desires. Live a life driven more by spontaneous motivation than self-flagellating discipline. Throw off your Taftian insecurities and fully own and embrace what you personally enjoy.

As Nietzsche said, “Become who you are.”