“I need your John Hancock.”

“He’s the prodigal son of our family.”

“That job was like working in the seventh layer of hell.”

“He has a Willy Loman-esque resignation about him.”

“We’re navigating between Scylla and Charybdis here.”

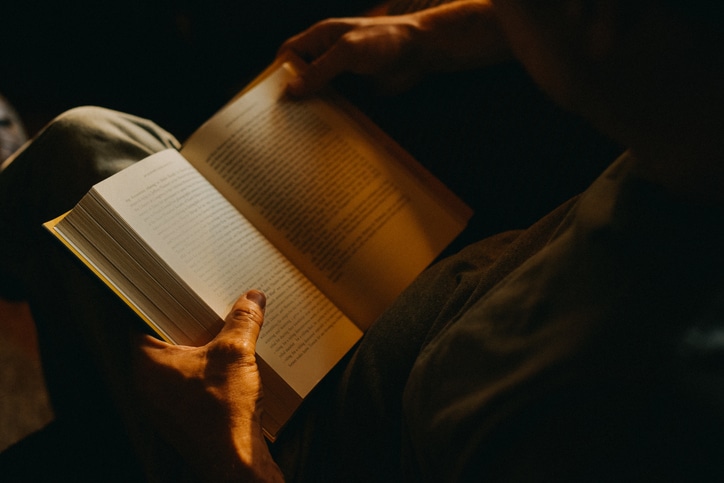

Anybody with the literacy of an eighth-grader could read those sentences. Heck, a third-grader could read those sentences without much problem.

But to really comprehend them, you’d have to know who John Hancock, the prodigal son, and Willy Loman are. You’d also need to be familiar with Homer’s Odyssey and Dante’s Inferno.

To be genuinely literate doesn’t just require mastering the mechanics of reading; it also requires having a breadth of cultural literacy.

What Is Cultural Literacy?

In 1987, literary critic and educator E.D. Hirsch published a book called Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know. In it, Hirsch made the case that for countries to thrive, citizens need a shared storehouse of knowledge — a shared cultural “vocabulary” — that consists of dates, names, literary references, idioms, concepts, and stories. He called this shared background “cultural literacy” and described it as “the context of what we say and read.” Hirsch argued that “All human communities are founded upon [this] specific shared information” and that it’s “part of what makes Americans American” (or what makes Mexicans Mexican or Ugandans Ugandan).

Cultural literacy isn’t knowledge of current events or information that’s only salient to one particular generation; rather, it’s knowledge that has stood the test of time and has stayed in a culture’s consciousness for years, decades, and even centuries. Cultural literacy isn’t just information about “heavy” stuff, like the arts and philosophy, either. Hirsch explains that it extends over all “the major domains of human activity from sports to science.”

Cultural literacy, Hirsch further explains, “lies above the everyday levels of knowledge that everyone possesses and below the expert level known only to specialists.”

Cultural literacy is the broad network of contextual information that helps us understand not only books but all media, from music to podcasts to movies. It allows us to dialogue with these mediums, and with each other. It allows culture to function, and if the literacy level is high enough, to thrive.

The Benefits of Gaining Cultural Literacy

Cultural literacy facilitates true comprehension. Hirsch was critical of American education, particularly for the way it had shifted from knowledge acquisition to skill acquisition. Reading comprehension was turned into the skill of decoding letters into words and connecting those words into sentences. But Hirsch argued that that’s really not reading comprehension. Sure, someone might be able to read a sentence, but if they don’t know what the words mean and add up to, it could just as well be written in Greek.

Writers write under the assumption that the average reader will already know certain things, without their being explicitly spelled out. Reading with real comprehension, Hirsch says, requires people being able to fill in these assumptions: “getting the point, grasping the implications, [and] relating what they read to the unstated context which alone gives meaning to what they read.”

A news article, for example, may mention a court ruling, Pakistan, the Civil War, or Joseph Stalin, without a lot of background details. Unless you already know some context — something about how the legal system works, where Pakistan is located in the world, the time period in which the Civil War was fought, and who Joseph Stalin was — you’re not going to fully comprehend the article.

As Hirsch puts it, “To grasp the words on a page we have to know a lot of information that isn’t set down on the page.”

Cultural literacy allows you to learn more. This is related to the above point; the more cultural literacy an individual has, the easier and the more that person can learn. Learning is an associative act. We peg new information to things we already know. As Hirsch observes, “The process of learning often works as metaphor does, yoking old ideas together to make something new.”

The broader your mental scaffolding, the more knowledge you can acquire; the more knowledge you acquire, the more expansive your mental scaffolding becomes.

Further, when you know a broad range of topics, you can spend less time learning the basics of things and more time getting into the nitty gritty. Having an expansive well of cultural knowledge allows you to speed up learning.

Here’s an example from my own experience: I read a lot of books each year as part of my prep for the podcast. Many of those books cite studies from the social sciences to make their points. Having a broad knowledge of the social sciences allows me to breeze through books quickly. Whenever I see “marshmallow test” or “invisible gorilla,” I can skip the sections describing those experiments because I’ve already read about them so many times.

Cultural literacy facilitates participation in the Great Conversation. For thousands of years, authors, artists, and thinkers of all kinds have been having a dialogue with each other. Novelists reference philosophers; philosophers reference novelists — even when their respective works are separated by hundreds of years. They’re talking to each other across the expanse of time. All writers and their readers “talk” to each other as well. In this way, we all can take part in history’s “Great Conversation.”

As mentioned above, there is a trend in the present age to emphasize the skills of learning over the mere accumulation of information. That is, the specific content of learning doesn’t matter as much as having the ability to acquire that content. That approach is more ascendant than ever in the digital age; after all, why embed facts, dates, and names in your head when you can access them from an external brain? Why memorize any information if you can google every question that arises?

Strictly “content-based” learning is indeed inadequate for becoming truly educated, and everyone does need to master the skills of learning. But “piling up specific, communally shared information,” as Hirsch puts it, still has a valuable role to play in everyone’s life. What we forget when we spurn the accumulation of information is how conversational learning and cultural engagement are — and how improvisational conversations are in nature.

Imagine having a casual conversation with a friend in which you had to constantly stop and refer to notes to remember what you wanted to say and to understand what they were saying; the conversation would be awkward, unsatisfying, and unfruitful.

In the same way, we cannot fully enter into, and add to, the “conversation” around the books we read, the podcasts we listen to, and the movies we watch unless we have a broad stockpile of knowledge at the immediate, impromptu fingertips of our minds.

We also cannot fully enter a cultural conversation with each other without a common background of literacy. The more knowledge we can assume that our fellow associates, students, and citizens share with us, the richer and more complex we can make our exchanges.

I always find it interesting to see how often old books will drop in untranslated phrases in foreign languages — French, German, Latin — assuming that the reader will perfectly understand them. Hirsch notes how his father would write business letters that quoted Shakespeare, and his employees readily understood the references without their needing to be explained.

Today, it’s harder to take shared knowledge for granted, so exchanges end up shallower and more rudimentary. Because there is so little we can assume everyone will get, we strip our communications to lowest-common-denominator references. Or simply exchange memes.

If our cultural conversations seem to have gotten stilted and dumbed-down, it’s because we need to bone up on our collective cultural literacy.

It makes life more interesting. When you have a high degree of cultural literacy, you pick up on a world of ideas hidden beneath the surface of a book, film, or TV show. Again, cultural literacy allows creators to assume upon their readers’/listeners’ storehouse of extant background knowledge; they can imply greater meanings without entirely spelling them out.

For example, it’s been interesting to watch my son Gus start to take an interest in The Simpsons — a show famous for the way its whip-smart writers make subtle-yet-hilarious references to literature, history, and film. Gus is only twelve, so he’ll laugh hysterically at Homer taking part in one of his zany capers, but then a funny allusion to Watergate will go completely over his head. He lacks the cultural literacy to get all the references.

It’s also fun to recognize the deeper, sometimes biblical, references embedded in the music you listen to. When Cake sings, “Sheep go to heaven; Goats go to hell,” or Brandon Flowers of The Killers sings, “When I came back empty-handed; You were waiting in the road; And you fell on my neck; And you took me back home,” I know they’re harkening to the Book of Matthew and the Parable of the Prodigal Son, respectively. As a consequence, those songs become richer in meaning.

The deeper your well of cultural literacy, the more deeply you can experience life. It’s like putting on a pair of 3D glasses.

What Should Every Culturally Literate Person Know?

Okay. Hopefully by now your interest is piqued in becoming more culturally literate.

So what should every culturally literate person know?

Well, that’s a question that’s caused a lot of debate since Hirsch introduced the idea 35 years ago. In the appendix of his book, he included a list of 5,000 words, dates, idioms, phrases, concepts, and names he thought every culturally literate American should know the meaning of/know something about. Here’s a random sample of some of the entries under A:

- Abandon hope, all ye who enter here

- absolute zero

- AC/DC

- Achilles’ heel

- Adams, John

- ad hoc

- ad hominem

- adverb

- Alcott, Louisa May

- Alger, Horatio

- Ali, Muhammad

- All the world’s a stage

- Alps, the

- Amazing Grace (song)

- anno domini (A.D.)

- Antarctica

- antebellum

- Apache Indians

- Appomattox Court House

- Arab-Israeli conflict

- Archduke Franz Ferdinand

- archetype

- Aristotle

- Arkansas

- Armstrong, Louis

- Articles of Confederation

- Ask not what your country can do for you . . .

- As the crow flies

- atheism

- Augustine, Saint

- au revoir

- Axis Powers

Scholars have critiqued Hirsch’s list as too text-based, male, and Eurocentric and have dismissed the idea of specific lists of knowledge in general as being, by nature, too exclusionary.

To that, Hirsch and other proponents of cultural literacy have argued, “Okay, use the list as a starting point and modify and add as you think necessary.”

While it may be difficult to agree on a list of shared knowledge every American should know, Hirsch and other scholars think it’s worth the effort to think about and debate what should be on such a list and try to impart as much of that knowledge to citizens as possible. Hirsch thought the most effective way to disseminate this knowledge was by making it part of every child’s education.

If you’re an adult who feels lacking in cultural literacy, read widely, look up things you don’t know, and try to commit those newly-learned words and concepts to memory.

If you’d like a quicker and more direct way to bone up, Hirsch also put together The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, which includes thousands of must-know topics with summaries of each idea. He divided it into sections like “The Bible,” “Idioms,” “American History Since 1865,” and “Physical Sciences and Mathematics.”

Hirsch thought every country should have a similar dictionary that compiled all the essential names, facts, and ideas from its particular culture.

I’ve used The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy as a starting point for improving my kids’ cultural literacy. I’ll just open it up to a random page, point my finger at a random entry, and ask them about it.

“Gus, who was W.E.B DuBois?”

“Scout, what is civil disobedience?”

I see what they know already (if anything) and then add to it by reading the short definition/description in the book.

One day, my finger landed on Buster Keaton, who Gus and Scout knew nothing about, so we watched some Buster Keaton clips on YouTube.

I’ve gone about the increase-my-kids-cultural-literacy project in pretty higgledy-piggledy fashion. It seems to be working, though. It’s helped Gus do well on his school’s academic bowl team, at least. Maybe one day he’ll start getting the more subtle Simpsons’ references too.

I’d recommend picking up a copy of Hirsch’s dictionary and going through it to enhance your existing education. It’s a great toilet read. Better than scrolling Instagram. Also, use it to augment your own kids’ education. Pick a random topic from the book each day and have a 2-minute mini-lesson about it. It will help your kids’ reading comprehension and learning ability, and ultimately, if all goes well, add another engaged and edifying voice to our cultural conversation.