With boxing on the wane in America for the past twenty some odd years, it’s easy to forget how much of a cultural juggernaut it was for much of the 20th century. Boxing was not only a common recreational pastime and athletic pursuit for young men, and a wildly popular spectator sport, it was a metaphor for manhood and other American cultural struggles as well. When two men stepped in the ring, it wasn’t just two men fighting. The bout could become a battle of white vs. black, nativist vs. immigrant, or democracy vs. fascism.

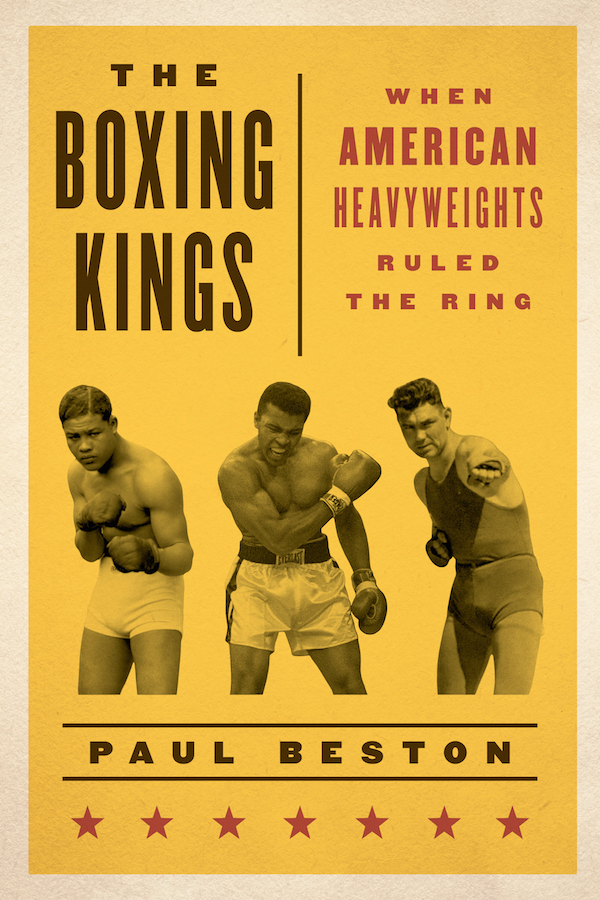

My guest today, Paul Beston, explores the cultural history of the heavyweight boxer in his latest book: The Boxing Kings: When American Heavyweights Ruled the Ring. Paul and I begin our conversation discussing the man who created the archetype of the American heavyweight boxer, John L. Sullivan. From there, Paul takes us on a vivid historical tour of many of boxing’s all-time greats, including Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey, James Braddock, Joe Lewis, Muhammad Ali, and Mike Tyson. Along the way Paul provides insights how each of these heavyweight greats became conflicted symbols of masculinity in America. We end our conversation discussing why boxing has declined in America and what Paul has learned about being a man from writing about boxing.

Even if you think you’re not interested in boxing, you’re going to find this show fascinating.

Show Highlights

- How did John L. Sullivan set the archetype of the American heavyweight boxer? What was Sullivan like as a fighter and sports hero?

- How is the heavyweight champ determined? How has that changed over the decades?

- The complex history of black boxers

- The crossover of literature, music, and theater with boxing and famed boxers

- How does this showmanship connection influence their boxing?

- Why Jack Dempsey was a character “straight out of a Jack London novel”

- How the Great Depression affected boxing, and why it in fact became a golden age for the sport

- Joe Louis’s rise, and how he came to symbolize democracy during WWII

- The ways in which Muhammad Ali fulfilled the Sullivan archetype, but in an even bigger way

- How Ali changed sport and celebrity in America

- The last truly great American heavyweight

- The aspects of Mike Tyson that people don’t know about, including his love of boxing history

- What led to the demise of the heavyweight boxer in American culture?

- What Beston learned about being a man while writing about the lives of these complex masculine figures

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- AoM’s “Boxing for Beginners” series

- AoM’s “Boxing Basics” series

- 14 Best Boxing Movies

- On Taking a Punch

- Boxing: A Manly History of the Sweet Science

- Podcast: The Life of John L. Sullivan

- James J. Corbett

- Jack Johnson

- The Great White Hope

- Max Baer

- The Prizefighter and The Lady

- Cinderella Man

- Joe Louis

- Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling

- Sonny Liston

- Larry Holmes

- Mike Tyson

- Klitschko brothers

- On Boxing by Joyce Carol Oates

- My podcast with heavyweight boxer Ed Latimore

Connect With Paul

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Big Questions with Cal Fussman Podcast. Best-selling author and Esquire columnist Cal Fussman talks to people who have lived extraordinary lives, from Kobe to Dr. Oz to Tim Ferriss. These are really deep, thoughtful conversations, and you’ll end up with burning questions answered, and a few new ones to think about. Subscribe to Big Questions with Cal Fussman now in your favorite podcast app, like Stitcher or Apple Podcasts.

Proper Cloth. Stop wearing shirts that don’t fit. Start looking your best with a custom fitted shirt. Go to propercloth.com/MANLINESS, and enter gift code MANLINESS to save $20 on your first shirt.

YourMechanic.com sends the mechanic right to your home or office. Get a quote up front, and pay that price. Visit yourmechanic.com/manliness to get $20 off your first service.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. With boxing on the wane in America for the past 20 some odd years, it’s easy to forget how much of a culture juggernaut it was from much of the 20th century.

Boxing was not only a common recreational pastime and athletic pursuit for young men and a wildly popular spectator sport. It was a metaphor for men who had other American cultural struggles as well. When two men stepped in the ring it wasn’t just two men fighting, the bout could become a battle of white versus black, nativist versus immigrant or democracy versus fascism. My guest today, Paul Beston explores the cultural history of the heavyweight boxer in his latest book, “The Boxing Kings: When American Heavyweights Ruled The Ring.” Paul and I began our conversation discussing the men who created the archetype of the American heavyweight, John L. Sullivan, the Boston Strong Boy.

From there, Paul takes on a vivid historical tour of many of boxing’s all time greats including Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey, James Braddock, Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali, and Mike Tyson. Along the way, Paul provides insights on how each of these heavyweight greats became conflicted symbols of mass culture in America. We’re in a conversation discussing why boxing has declined in America, what Paul has learned about being a man from writing about boxing. Even if you think you’re not interested in boxing you’re going to find this show as fascinating. After it’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/boxingkings. Paul joins me now via clearcast.io. Paul Beston, welcome to the show.

Paul Beston: Thanks, Brett. Great to be with you.

Brett McKay: You got a book out, “The Boxing Kings: When American Heavyweights Ruled The Ring.” The heavyweight boxers were like this archetype of manliness. In fact, we’ve got our logo, the Art of Manliness is based off of the very first American heavyweight boxer, John L. Sullivan. What I love about this book not only is the stories of these individual boxers are interesting and fascinating but boxing says a lot, you can learn a lot about American culture, the evolution of it, by studying or reading about the lives of these American boxers. Let’s start off with the very first one, John L., John L. Sullivan. How did he set the archetype of what we think about when we think of a heavyweight boxer?

Paul Beston: John L. Sullivan who was champion from 1882 to 1892. I call him in my chapter on him the George Washington of boxing and that’s certainly in United States and that’s really what he became because just as Washington kind of created the Office of the Presidency, John L. Sullivan really creates the office of heavyweight champion. There have been champions, a few champions before him but they didn’t reach anything like the kind of recognition that he reached. Boxing was an illegal sport. It would remain illegal during his time but what was different during Sullivan’s career is that his fights were covered in what the equivalent of the mainstream media. They were covered in newspapers and some of them were even covered internationally. He just became a figure known far and wide, known all around the United States and he’s really one of the most famous Americans of the gilded age.

The previous champions such as they were before Sullivan didn’t have anything like that kind of notoriety. It was really a kind of back alley affair. The champions attained a certain fame among the fighting fraternity but Sullivan just completely transcended the fighting fraternity. He became a figure in songs and literature and art and a great hero to Irish Americans. He was a son of Irish immigrants. He’s born in Boston in 1858. His career it traces the whole second half of the 19th century with the post civil war and the rise of the cities and the mass wave of immigration especially the Irish and also the rise of modern commercial sports which he has a huge role in bringing about.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I mean, he was really one of America’s first big celebrities. He birth America’s celebrity culture.

Paul Beston: That’s right, he really did. He’s really the first sports star. I mean, baseball was getting going during his career. The major league, national league started at I think it’s 1876 or so. He’s really the guy who pioneers this whole idea of stardom and celebrity itself in America was just coming into being in the way that we would think of it. This figures who are equally adulated and reviled, you know, because he was a very controversial figure too because of his personal life. He was a terrible alcoholic and he had all kinds of misadventures. He had his many people hating him as loving him. We’re very familiar with that dynamic today with celebrities and with athletes. He’s really at the forefront of all that, because of the force of his personality and the force of his fighting skill he makes the heavyweight championship this prominent thing that even people who don’t follow boxing know about. It had not been that before. He really comes into a void and he leaves behind a whole world.

Brett McKay: When you’re talking about his personality and the force of his personality, the guy was a character. He’d walk into rooms sometimes and he was known to say, “I can lick any son of a bitch in the house.”

Paul Beston: Right, right.

Brett McKay: He meant it, or that you talk about how whenever … He would just be talking to people and whenever he finish what he said he would say, “Yours truly, John L. Sullivan.” He would sign his name in the air.

Paul Beston: That’s right. He had this great thing about himself. He’d like to always say, “Always on the level, John L. Sullivan. Yours truly, John L. Sullivan. Always on the level.” One of the things I try to get in the book too is that he and all these guys really will show especially the great figures is that somewhere along the line they developed this notion of themselves. You see that in a lot of great celebrities and great figures in history. Somewhere along the line they develop a notion that they have something, has something special and there’s some reason that the world should pay attention to them. I think what’s unique about Sullivan is that he seems to decide this when he becomes champion and again, there would had been no president for thinking before these other guys just kind of again, like I said a back alley thing. These guys were not huge, prominent figures but he decided when he won that title that this was a big deal and that he was a big deal. He preceded to then make it a big deal through his own career.

Brett McKay: You’ve been talking a lot about his personality. What was he like as a fighter? Was he really, really good?

Paul Beston: In today’s world, we have this age of advanced athletics and we’re always looking back at this … I see this a lot on the internet, it’s always comparing former athletes from earlier eras and it’s very easy for us in our age to look back some of these black and white images of baseball or football players and think, “Gosh, they could have been very good. Look at the way they move, look at their bodies, they’re not as big, they’re not strong. It don’t look like they’re fast.” Of course, we’d have to project those guys into the present day with all of the advantages we have today and so any athlete can ever do is be great in his own time. When Sullivan came along there had never been anything like him. Boxing I should say was I mentioned that it was illegal but it was also when he first started out was largely still being fought with the barefist under what was called the London Prize Ring Rules and it was just starting to move into using gloves which Sullivan supported. There’s two different sets of rules. There was the gloved rules which was the beginning of what we know today in modern boxing.

There was also this bare-knuckle style of fighting which was rather different and in some ways is kind of a precursor to mixed martial arts because you could do wrestling holds. You could take a guy down similar to in wrestling. You could do headlocks while also punching. He was adapted in both of these styles of fighting and he just had a level of aggression and his right hand punch that people who had been watching this for a long time had not seen before. He always had this line, something that, “From the moment the bell rings I’m out to win. I go in to win, win I must, and win I shall.” It was the kind of electricity that he brought to it that hadn’t been there before. How would he stack up against today’s modern fighters, who knows? I’ll say this, I wouldn’t want to fight him in one of those fights to the finish where there’s no time limit, that would be daunting.

Brett McKay: That was another thing I didn’t realize about bare-knuckle boxing. There were rounds but you only got like I think how long, like 30 second break. It was something not that-

Paul Beston: That’s right. Yeah, there were 30 seconds between rounds instead of 60 seconds today and the rounds ended only when one man went down with the call of fall. That fall could be from a punch, it could be from a wrestling toss. It could be just taking a knee on your own volition. A round could be 10 seconds long but it could also be 15 minutes and some of them were. These fights would go on for let’s say 60 rounds, 70 rounds, 80 rounds. Of course, that sounds like, “My god, that must be unbearable.” Again, I mean, to be fair, some of the rounds were very, very short. On the other hand, you’re out there for a long time and the rest periods are shorter. There’s no judge, there’s no judges and score cards and all those controversial decisions that boxing fans rue every year. They didn’t have to deal with that. The fight only ended when one man could no longer continue whether he was counted out, count of 10 or he just couldn’t fight anymore.

Brett McKay: He wins the heavyweight championship. Let’s talk about this, here’s interesting because I think this will help listeners with the rest of discussion like who determines who is the heavyweight champion? How did people decide that John L. Sullivan was the heavyweight champion of the world and how do we figure that out today because there’s like three different branches of boxing out there?

Paul Beston: I’ll answer the older question first because it’s easier. Today is really a mess. Sullivan won his title by defeating a man named Paddy Ryan who was called the champion. Paddy Ryan was called champion because he’d beaten the fighter previous to him. Again, boxing was an illegal sport, it didn’t have a commission or organizing body so it was, “Who is the champion?” The champion was essentially by acclamation by the people who organize the fights, people who are competing in it. Then, at some point there came to be a recognized champion and once that guy was recognized generally by consensus then it would be pretty easy to determine who the next champion was because it would be whoever would beat him. That’s the traditional way in boxing of course. You become champion by beating the champion. You don’t become champion by saying you are or having some shady organization say that you’re a champion without having done that.

There’s an old saying in boxing, they call it, “The man who beat the man who beat the man.” That’s what they call today the lineal title, in other words, it can be traced backwards in time through all the guys who held it. Once Sullivan had really established this and made this a prominent thing and he lost his title in 1892 to a guy named James J. Corbett and James J. Corbett was the heavyweight champion. From there, the whole story unfolds in a pretty straight line through most of my book fortunately. It doesn’t get too confusing till near the end of my book when multiple organizations, sanctioning organizations begin to come into the sport starting around early 60s but really taking off in the 70s and 80s.

When I got into boxing in the 70s as a kid, even then there were two champions in each division but that looks like a golden age compared to now because now there’s three sometimes four champions in each division and that’s because these sanctioning organizations all name their own champions and they tend to be jealously guarded about making sure they don’t fight the other guy’s champion because they don’t want to lose theirs. They want to keep the title under their tent. It’s a very unsatisfying arrangement, the boxing fans have been complaining about it forever. It didn’t reach the heavyweight for a while because the heavyweight were so prominent and had such giant figures like Muhammad Ali.

It’s very hard to imagine the public accepting two heavyweight champions but eventually it did trickle down to the heavyweight, trickle up I should say to the heavyweight division as well and today there’s I think there’s three guys who claimed some piece of the heavyweight title. I mean, what I compare to is imagine if there were two or three football teams walking around saying that they were the Super Bowl champion, I mean, nobody would take that seriously.

Brett McKay: Right, hence the decline of the heavyweight in American culture. Going back to Sullivan, he was both celebrated and reviled. This guy, he lived a hard life. Drink a lot, lost a lot of money, had a whole bunch of … He was married a couple times, divorced. What was interesting, he would get incredibly out of shape but he would somehow muster up some sort of will power to get into fighting condition and try to win another fight.

Paul Beston: Yes. He was quite good at that. The drinking was a big part of the boxing culture. From the beginning, I mean it was this very much a working man’s subculture. An immigrant, heavily immigrant and the Irish were just very, very prominent in the early days of boxing and there’s a lot of drinking in Irish culture. These guys it was very often that former fighters would just really end up in the gutter essentially as drunks and usually quite poor. Sullivan fit right in there and he had olympian appetite for food and booze and he would get grossly overweight between fights. A few fights he came into the match clearly terribly hung over and he couldn’t even perform.

As I was saying earlier, his public reputation was it was huge and it was large but it was also conflicted and complex because there’s as many people criticizing him sometimes as cheering him. When he got motivated, he would get himself into shape and the thing that you could surely motivate him with most of all is suggest, even suggest that you could beat him and that you are somehow the rightful champion. You get his goat. He had a pretty strong temper. If you got his goat, get him motivated, he was going to work himself into shape and then you’re going to have quite an opponent on your hands.

Brett McKay: You said he only lost one fight I believe, that was against Corbett. He lost a couple, did he lose any … I thought he was undefeated except for Corbett.

Paul Beston: He was, he was undefeated except for Corbett. He had another match that ended essentially in a draw and was kind of demoralizing to him but it was not a defeat. The only fight he lost was the last one of his career to Corbett, that’s where he lost the heavyweight title.

Brett McKay: Did he fight after that?

Paul Beston: He fought exhibitions for many years on and off and then there was a kind of miraculous thing that happened in 1905 where he actually got back in the ring. It was late 40s and grossly overweight, against a plausible professional fighter, a young man and knocked him out with one punch in the second round. This was in Grand Rapids, Michigan and the place just went crazy. It was almost just like a bolt from the past. His career was essentially over after he lost to Corbett.

Brett McKay: I thought it’s funny, even when he lost to Corbett he gave this consolatory speeches.

Paul Beston: Yes.

Brett McKay: Ended it with, “Yours ever always, John L. Sullivan.”

Paul Beston: That’s right. He also said in that speech which I think is interesting is that he was, if he had to lose he was glad he could lose it to an American. That was very important to him. Of course, Sullivan didn’t see, didn’t tend to include blacks in the description of Americans and of course that’s one of the clouds over his career because he is the man who drew the racial color line in heavyweight boxing and refuse to give black challengers a shot. That shadows his career and his accomplishments but he was very proud of being an American and he wanted, he very much saw the title as something that Americans should possess and be proud of.

Brett McKay: Sounds like Bill the Butcher from Gangs of New York. We’re going to talk about the color line here in a bit but I thought it was interesting too. He had this life of just ride his living but it seemed like he tempered out in old age and got his act together a bit.

Paul Beston: He did. I think that’s something frankly under remarked about him and I was really struck by it again recently because as we’re recording this, tomorrow is the 100th anniversary of his passing actually, February 2nd, 1918. I was looking up some things and writing a few things about it. His late in life turn around is pretty remarkable. I mentioned that miraculous fight he had in 1905 where he just had this bolt from the blue. Not long after that he’s sitting in a hotel bar with a glass of champagne and he just suddenly said, announces out loud, “This is it, I’m not drinking anymore.” He pours it into a spittoon. His friends kind of chuckled they’ve heard this before but he means it and he never drinks again. He winds up becoming a temperance lecturer and he remarries an old childhood friend, a woman named Kate Harkins. They take in a young orphan boy who they really doted on. He start a small farm in Massachusets. He becomes very popular around town. Little children love to come and play at the farm. He really does end his life I think in a place of peace, some redemption.

Brett McKay: Let’s get back to the color line. I think often times we think of American sport, and the color barrier and breaking it, we often think of baseball and Jackie Robinson but boxing actually lead the way in racial integration in sports. When do we first start seeing integrated fights in America?

Paul Beston: They actually go back pretty far. They weren’t very common which I’ll get to in a second but there were black champions in the lower weights. There was a fighter named George Dixon who won the featherweight title in the 1890s. Then in the very early 1900s there was the great Joe Gans who was the lightweight champion and still regarded today as one of the greatest, maybe the greatest lightweight who ever fought. They would happen sometimes at the lower weights but it was always a conflict around it because of the racial environment at the time. There was a lot of discomfort about seeing black men and white men get in the ring together and some people would say, “Well, it’s going to cause tensions between the races or it’s going to cause trouble.” The underlying fear really was what happens if the black guy wins. That was a real fear. This is a time of not only tremendous racism and Jim Crow had gone into effect in the south but also these, “Scientific theories,” of racial superiority or the Anglo race and the inferiority of the African races.

Some of these was also directed at other ethnicity such as the Irish but obviously it was the worst of all for blacks. There was just a lot of discomfort about that that getting the two races in the ring together was going to lead to nothing but trouble so it didn’t happen that often but on the other hand, blacks did probably had more opportunity in boxing than they had elsewhere. In a funny way, boxing’s illegality probably helped them in that sense because again it had this informal nature to it unlike major league baseball which was already banning blacks by the 1880s. They kept them out of the heavyweights.

That was the big thing. The prize that the Citadel that blacks were not to approach was the heavyweight title. Of course that again goes back to Sullivan drawing that color line. He would have had a lot of support for that but he did take it upon himself to declare that and it’s fascinating to wonder how history might have gone differently if he had not done that but he did and so it was a very powerful bar to blacks having any chance at the heavyweight title for the early history of the championship.

Brett McKay: When did you start seeing African Americans fighting for the heavyweight championship?

Paul Beston: It just happened out of the blue in 1908 with the arrival of Jack Johnson who had been an outstanding challenger for a while. There had been outstanding black challengers before him and people like Sullivan and others had denied them a title shot but Johnson came along. He was the outstanding challenger. He had some support in the press and the biggest thing was that they found a promoter who could offer the white champion at the time, a guy named Tommy Burns who said, “I’m not going to fight a black fighter but if you give me $30,000 I will.” Lo and behold, they came up with the $30,000 so they finally made the match. It wasn’t really the result of any great change in social attitude, in fact it was the opposite because the match was condemned by many people including Sullivan who thought that Burns shouldn’t be doing this.

Johnson goes on and just takes Burns apart and beats him decisively and becomes the first black man to win the heavyweight title. They were really after the race because now you’ve got a black man at the top of the heavyweight division which has already by 1908 become the heavyweight championship has already become a prize of real value and symbolism to Americans. Again, going back to Sullivan and his success was really seen as a symbol of national power and manhood. When they say manhood, they mean white manhood. Johnson instantly enters the pages of boxing history because his whole career is going to be a mirror of the country’s racial situation. It’s not a happy picture.

Brett McKay: What’s interesting is that Johnson, even though he broke the color line that Sullivan set in place, he followed Sullivan and fitting himself to the archetype, this bigger than life character that a heavyweight champion. This guy, he lived larger, a lot of personality would be a good way to say it.

Paul Beston: Yeah, it’s funny. They’re kind of kindred spirits and in a funny way I think Sullivan came to actually like Johnson. He spent a little bit of time with him in 1910 when Johnson was engaged and had the biggest match of his career against former champion James J. Jeffries. This was a fight that became the biggest fight in history of boxing at the time. It was on July 4, 1910. Jeffries was a former heavyweight champion. He was white. This was where the phrase the great white hope comes from. He was seen by millions of whites as their chance to take this title back and prove once and for all the races are not equal, that the white men is rightfully on top. It’s just a fight loaded with so much social tension and significance. The heavyweight title has meant a lot to people for a long time and certainly during the history I talk about in the book but there are a couple points in the history where it means a little too much.

It means more than any athletic contest should and this was one of those times in 1910. There’s just too much writing on this. It’s not healthy. Johnson wins the match easily and after the fight is over and the days subsequent, there’s race riots across the country. Terrible race riots and the deadliest in the country before the 1960s. It’s really again as I said really a mirror of where things were at that time and the fear, the tremendous fear that Johnson tapped into among whites, of blacks showing ability in this area. Back to Sullivan real quickly, he ends up on a train with Johnson riding home from the fight and he was also the first man to step between the ropes and shake his hand when he won the fight. It’s interesting seeing his reaction to Johnson.

Brett McKay: What’s interesting about when I read about Johnson was that, okay, obviously white America was not a fan of them but there’s also a lot of people in the African American community that didn’t really care for them either. What was the dynamic between Johnson and African Americans?

Paul Beston: I think there’s two reasons for that. I mean, one reason is he’s so unpopular that there’s a fear among blacks that he was really just going to make things harder for them which was a perfectly reasonable fear to have. In fact, subsequently after his career it’s a long time 20 plus years before another black fighter gets a chance at the heavyweight title and that was the shadow of Johnson. Black boxers didn’t regard him very fondly at all in the years after. It’s really been more recently since the 60s that we’ve looked at Johnson and seen him and celebrated him more but he was really looked upon a little bit more notoriously in the early stages of his career. Part of this also is because he was not someone who’s exactly leading an exemplary life.

He was like Sullivan. He loved the sensual life. He love night clubs, he love fast cars, he loves alcohol. His particular fondness was not just for lost of women but for prostitutes. Many of his consorts were prostitutes. He married prostitute. That kind of behavior would have been scandalous for a white champion to some degree but for a black champion this just made Johnson such a lightning rod for every conceivable kind of criticism. Some blacks were really worried that he was setting a bad example for the race. Others of course certainly admired him and celebrated him. The guy going into the ring and beating white fighters. He was a complicated figure.

Brett McKay: Definitely. I thought adding that complication, he even had his own color line. He wouldn’t fight other African Americans for some reason.

Paul Beston: That’s right. As champion, he did not. Coming up, he fought black fighters all the time including several great boxers who are still remembered in boxing history, black fighters who didn’t get their chance. He fought them repeatedly because that’s who they could fight. They’d sometimes couldn’t get matches with white fighters because they were too good. Once he became champion, he saw no reason to give those guys a chance. He was a businessman. There’s one thread that runs through the title that all these guys have in common, this is a business. You get that title, you’re going to hold on to it with all that you’ve got. Johnson saw no reason to give them a chance. Also, because it wouldn’t be economically very appealing because the racism in the country at that time, two black men fighting for the title had no appeal at all. Near the end of Johnson’s title career he does gave another black challenger a shot but it’s not one of those top guys I mentioned. It’s a pretty mediocre fighter.

Brett McKay: Right. Just to give you idea of how entwined boxing was in American culture, the guy who came up with that, the great white hope phrase, that was Jack London, the novelist. I guess he wrote a newspaper article asking about that. Something like literature was tied. Everyone was keyed in on boxing during this time.

Paul Beston: Yeah, it really was. It would stay that way through most of the period that I chronicle through my book. I mean, that’s one of the most remarkable things about the story is how much it extended out beyond the ring, not just these political and social things that we’re just talking about. How many writers were drawn to this, drawn to the ring and drawn to the figures of the rings and going well forward into the 30s and 40s? Figures like Richard Wright and later on James Baldwin. Obviously, Norman Mailer wrote a lot about boxing. The writers just go through the history of it. There’s a lot of kinship between writers and boxers. I think this is solitary nature of what they have to do. It started with Sullivan as well. I mean, Sullivan was a figure of fascination from the very beginning.

Brett McKay: Speaking of Jack London, you say that one of the next big heavyweights, there are some other ones but the next one that really had a big cultural impact on America was a guy you said came straight out of a Jack London novel, that’s Jack Dempsey. What was it about Jack Dempsey that made him so captivating to Americans?

Paul Beston: Well, I think he’s the next figure from Sullivan in that sense of bringing something new to the style of fighting. He brought a speed of attack and aggressiveness to boxing that it had not … Just hadn’t seen before and there’s something very symbolic about it. It’s just that the era when we’re moving into the 1920s and all these technology is going to start coming in, the radio, the motion pictures are still fairly new. Dempsey, it’s the real analog for Dempsey later on in history as Mike Tyson. A lot of listeners will have associations to Mike Tyson. They’re old enough to remember when he first came along in the 80s, how exciting that was and how people would say, “I get the Tyson fight on the first round because there may not be a second round.” That was what Dempsey was like when he came along. He had a whole string of knockouts in the first round, second round.

He attack from the opening bell. He presented himself. He would come in with this what they call the hobo hair cut. He looked very rough. He’s a guy from the west. He had a tough wandering life before he ended up as champion. He tapped into a lot of I think archetypal images that have endured in boxing ever since. It was his aggressive style that captured people just at the point in the roaring 20s when sports was going to explode. When Babe Ruth was going to start hitting home runs and the radio was going to come in to be able to bring sports to people in mass numbers. Dempsey comes along and he’s not a defensive fighter. He’s not a cautious fighter. He just puts it all out there in every fight and every round.

It makes him, you could still argue the greatest draw in the history of boxing because while the pay per view receipts of recent years exceed everything in dollar value, Dempsey was bringing bodies into the seats, 100,000, 120,000, 150,000. People come into these fights and traveling on trains from different cities to get there. This guy really got people’s interest.

Brett McKay: Did he tried to take that fame he gained in the boxing ring out to other areas to start other businesses tapped with that celebrity?

Paul Beston: Sure, that’s a great point and that also starts with Sullivan is this whole idea that you can take this title and the real value of the title in a way is outside the ring because when you’ve got that title it’s your calling card to get you into whole kinds of, all kinds of other ventures. In Sullivan’s day it was the stage in Vaudeville and Jack Johnson did that too. Jack Johnson was a pretty good musician. He conducted his own little jazz band and he performed on Vaudeville stages. All the champions did even if they didn’t have any performing skills they would show up on Vaudeville.

They’ll just talk, they might just recite something or they might just explain how they won their last fight. They would get them out there to do something so the people could come and see them. Dempsey has a good fortune of not just having that but in the 20s of course Hollywood is really blooming. He gets all kinds of work in Hollywood and silent films. He starts making more money outside the ring than he does inside of it. That’s one reason why as his title years wound on he fought less and less because he’s just making so much money doing other things.

Brett McKay: People would make movies just for him to be in.

Paul Beston: Yeah, that’s right.

Brett McKay: He got a bit line and that was it.

Paul Beston: Yeah, he just play a good guy saving the girl. Just very stock sort of plots but people want to see him. He went on the stage with that kind of stuff as well. I think at one point he said, “I think I almost destroyed the American theater.” He’s always pretty self-deprecating about his talents but he was in demand.

Brett McKay: Right. The same thing with Sullivan. He played the blacksmith in some play. It was really bad supposedly, it wasn’t that great of a play but he would say his line then do a little boxing exhibition and then you make a ton of money.

Paul Beston: When he would say his lines and they would cheer and applaud in the middle, he would start over.

Brett McKay: Some of these boxers they box and they became theater or movie stars but there were some actual legitimate thespian boxers like James Corbett. I think he was an actor like a legitimate actor. There were some guys who they were actors, they got into boxing and then they went back to acting. Tell us about some of these famous thespian boxers.

Paul Beston: Corbett is definitely the most accomplished. You’re exactly right. He really was good at it. Again, he first parlayed from boxing. I mean, he saw the title as his way to get into this but his acting career lasted for the rest of his life. It wasn’t just bit parts, it was a working career and it wound up encompassing plays, comedies, Vaudeville, even some silent films and there are number of biographies on him and one of them focuses entirely on his performing career non boxing that is. He died in 1933 so you’re talking about a 40 year career in theater. He helped form an actors union in Broadway. He really had a very distinguished career. He’s pretty good. Most of the other guys were not of that caliber. A guy who probably could have been a star and certainly thought he should be and wanted to be instead of a boxer was a champion who was a very brief champion, Max Baer from the 1930s.

One of my favorite characters in the book because he’s just such a lovable character. He’s just richly funny, a terrific sense of humor, and that was a problem for him as a boxer is he was too busy making people laugh and didn’t really have the killer instinct that a great champion needs. He was real caught up and he made one movie with Myrna Loy, 1933 called, “The Prizefighter and the Lady.” This is actually quite good. It’s a romantic comedy and he sings in that not very well but he’s very captivating. He has a great screen presence and I think he saw the heavyweight title as his way to get into that career but it didn’t quite pan out. A little sequel to that is his son, Max Junior wound up becoming a star on The Beverly Hillbillies. Whenever I mention Max Baer, that’s what people seem to remember is Max Junior, Jethro. You know these guys they always later on would take their shot at singing.

Singing became big thing. Even Muhammad Ali if you go on YouTube you can hear him sing when he’s still known as Cassius Clay. A pretty passible version of Stand by me. It’s not bad. He was hanging out with Sam Cooke so Sam was helping him out there and Joe Frazier had a long singing career. He grown up signing in the church in South Carolina. Sometimes he sounds a little rough, other times he sounds pretty good. They did always see this title as some way to get into another life and even write ups to the present day we’ve got Mike Tyson who’s got a whole second career now as a performer.

Brett McKay: Right. How do you think this connection, this showmanship influenced boxing? Did they bring that to the ring or how they entered the ring or their boxing persona?

Paul Beston: That’s a great question. Boxing is by far the most theatrical sport. I just think the two things go together like bread and butter. I have a friend who actually writes about this quite a bit and he points out that boxing and the theater are really cousins to one another. The stage and the ring, lighting is very important. The action takes place in a limited space. You’ve got your attention focused on two players. Even great matches often seem to have a play structure to them sometimes even before the match all the stuff that goes into setting them up and all the side stage dramas about how the fights get made. Then there’s just that whole element of really great theatrical element in every boxing match even if the match turns out not to be good is that entry into the ring of that aisle that each guy makes.

You can’t get much more theatrical than that, the disrobing, you’re taking the robes off and all your supporters are going to step to the ropes and leave you there alone to make your case against your opponent. I think that the boxers had a natural inclination to pursue the stage because in many ways they already run a stage, they were performers and much more than other athletes who play in teams and sometimes they’re just a cog in the wheel. Boxers are used to being the star.

Brett McKay: After Dempsey, we move into the depression. How did the great depression affect boxing?

Paul Beston: It was actually, most histories of the sport really regard the depression in a ways of golden age because economically things are obviously very hard and if you look at the gate receipts of the big heavyweight fights especially in the early parts of the 30s, they’re way, way, way down from what Jack Dempsey was pulling in in the 20s. It’s really reflecting the economic climate but the promoters started cutting ticket prices. The biggest thing was that boxing is like the movies in the 30s. It was one of those tonics, one of those few tonics that people had to divert them from the other hardships that were going on in the country. It was also a time of just incredible ethnic diversity in boxing. The Irish were still on the scene but the Italians were now becoming very prominent.

Black fighters of course were still in the mix and eventually they’re going to get their crowning glory in the mid 30s when Joe Louis shows up at the heavyweight level. There was tremendous interest in boxing. Radio was now fully established. The 30s and the 40s it doesn’t get much better than that for boxing. Everything since then is pretty much a slow steady trickle downward from that peak. Boxing and baseball were the top sports in the country. Football, the NFL it existed but it wasn’t anything like what it was today. The NBA, these things were not on the scene, they were not factors. Boxing was a major league sport, a mainstream interest.

Brett McKay: It seems like the depression added to the drama of the sport like the Cinderella Man, James J. Braddock.

Paul Beston: That’s right.

Brett McKay: It’s an amazing story.

Paul Beston: Yeah, it really was. It just connected with people everywhere. That was really, the heavyweight title, the great champions like Dempsey or Sullivan or Johnson, they do tend to be even though they come from usually a pretty common circumstances, they tend to be elevated. At some point they become godlike but in the 30s it was much more approachable. Again, it was just that sense of the depression. James J. Braddock, the Cinderella Man, he literally is the guy next door. He was a fighter. He’s a long time fighter and a good one but he had fallen on very hard times just like everybody else. He lost a whole bunch of fights and he’d been written off years before then until he made this incredible rally which is pretty well portrayed in the movie with Russell Crowe. The great thing about that story is I always tell people it’s actually true.

Brett McKay: Right. I thought it’s amazing, a lot of these boxers including Braddock, once they made their winnings they would go back to the welfare agency where they use the support and they would pay them back. There’s that sense of dignity that they wanted to regain.

Paul Beston: Yeah, that’s a famous part of Braddock’s story and one of the most exciting surprises for me in writing this book was that I discovered two other guys who did it as you’re just alluding to. I had no idea that Joe Louis had done the same thing. Joe Louis is remembered for so many other things. It’s no wonder that that detail is lost. Jersey Joe Walcott who’s a champion briefly in the early 50s had also been on relief with his family and also paid the agency back. It does really tell you a little bit about those times and the way people saw things like that.

Brett McKay: Speaking of Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber, this is another boxer where his race embedded his career with a lot of meaning underneath the fight. What was interesting about Joe Louis compared to Jack Johnson, he became the symbol of American democracy for both African Americans and whites. Tell us about his rise to this symbol of America during world war two.

Paul Beston: Joe Louis is really a giant of the story, a giant of the whole history of the heavyweight title. When you look at those top ten list of people love to make, anybody who’s knowledgeable it’s usually two guys they’re at the top two spots, it’s Muhammad Ali and Joe Louis and sometimes the order is reversed but it’s always those two guys. Joe Louis for the longest time was regarded as the undisputed greatest heavyweight ever. As a boxer he has very few peers when he came along in the early 30s as we were talking about blacks hadn’t had a shot at the heavyweight title since Johnson had lost it and Johnson lost it in 1915. It was going on 20 years when Joe Louis showed up. Louis’ talent was just off the charts. I mean, it was off the charts as an amateur and as an early pro. He was born in Alabama but he grew up from around age 12 or so in Detroit. He’s fighting out of Detroit and that’s where he discovered boxing when he was supposed to be taking violin lessons.

Another one of those great details. Once his potential was clear to his management team, they became determined to really pull off the impossible which was get him a shot at the heavyweight title and one thing they realize is that that would not even be a possible at all if he struck any cords that reminded people of Jack Johnson. They famously drew up a set of rules about how he was to conduct himself in public and some of those rules included never being seen with a white woman but also never doing other things that Johnson had done such as gloat over opponents again, especially white opponents but really any opponents. Not to be seen out in nightclubs by himself or with another woman, that kind of stuff. There’s a whole bunch of different things he was not to boast over opponents. The thing that’s funny about those rules, people make a lot of those rules, they make a lot of those today and they are important but the thing is Joe Louis’ personality was perfectly consistent with those rules anyway.

He was a soft-spoken person, he was not like Jack Johnson, it would never have occurred to him to boast over an opponent anyway. The rules fit him pretty nicely, it wasn’t like any great effort for him to pull that off. He certainly had his female liaisons but he was discrete about it. He makes his way up, he’s knocking out everybody in sight. He just became impossible to deny and that he finally got his chance at the title against Braddock who we were just talking about and knocks him out in 1937 to become the heavyweight champion. Second black men to win the heavyweight title, first one in 22 years and there’s still a ton of racism directed at him. There’s more goodwill than there was for Johnson but one of the things that really stood out for me in working on Louis was reading the old newspaper articles and the language that’s used especially by writers who are nominally on Louis’ side.

They think that they’re praising him, they mean to praise him but they’re using all kinds of condescending and racist language to talk about him. That was the climate. Two things really send his career into the next realm. First is that he has this great rivalry with Max Schmeling from Germany who becomes Adolf Hitler’s favorite fighter during the 1930s remember. Schmeling is adopted by the Nazi regime as the symbol of Aryan supremacy and strength and in his first match with Louis he knocks Louis out. Louis’ first loss as a professional and a huge upset not expected. Through a series of a complicated moves Louis gets a shot at the title before Schmeling and so he’s the champion, Schmeling comes back to the United States two years later in 1938 to have a shot at the title against Louis. The big grudge match, this is a match on the levels of the other one I was mentioning before, Jeffries and Johnson. Just one of those times that title might mean almost too much. He got Hitler buying into it, the Nazis see their whole racial theory writing on Schmeling.

Meanwhile, Americans are rooting for Louis. Certainly blacks, certainly Jews want to see Louis win but one of the transforming turning points in the story is that more and more whites come to root for Louis because they see him as the American fighter not as a black fighter. This not to say that there weren’t plenty of whites also rooting for Schmeling there’s certainly were but they showdown in … They confront one another in Yankee Stadium in June 38 and Louis with the pressure of the world on his shoulders really, I think more than any athlete has ever faced just destroys Max Schmeling in two minutes and it’s on YouTube you can watch it. It’s kind of amazing thing to watch. He wins that fight and makes him a huge hero. Among blacks he’s at a level that is, I mean, there’s just nobody more celebrated in black America than Joe Louis.

Time Magazine calls him the Black Moses and he just goes on this long, long championship reign. He holds it for longer than any other champion, defends it against more challengers than any other champion. In the final page in the saga the war comes along and he suits up for the US army and again this wins enormous goodwill from white who just start to see this guy as an American, as a fellow citizen and as a hero and he even donates purses from two of his fights to the armed forces. He just reaches a level of kind of nobility and dignity that very few athletes have ever had and by the end of his life, the end of career I should say, he’s fighting white opponents and white people at ring side are rooting for Joe Louis. By the time his career ends, there’s still very long way to go on race relations needless to say but all of the legacy that he left behind as best I can tell is just entirely positive, it’s an amazing career.

Brett McKay: Speaking of Max Schmeling like he and Joe Louis become really good friends later in life just another interesting story.

Paul Beston: Right, yes, they did. Schmeling lived a very long life, he lived till nearly 100 and after he served in the German army and then after the war and post war of German he eventually made his way to the United States and he really wanted to connect with Louis. He wanted to kind of go over the past with him and connect with him and that later fight that they had and they make the connection. Louis has no ill feelings and they did become good friends as older men.

Brett McKay: After Louis there’s a series of heavyweight champs and we can talk about, there’s Rocky Marciano but we can’t, in this conversation we can not talk about Muhammad Ali, the greatest, right, as he said.

Paul Beston: Yeah.

Brett McKay: What was it about Ali that made him such, I mean he, again, he’s filling that archetype that Sullivan set that you’re going to be larger than life, it’s going to be about you. Something about Ali like he had this like really big impact not just on boxing but on the culture in America. How did Ali change boxing but then also how did he change sport and celebrity in America?

Paul Beston: When I was growing up as a kid in the 70s and just stumbling into boxing, he was the champion at the time and it was kind of a blessing and a curse on the one hand, boy that’s exciting to grow up with him as your first champion. On the other hand who’s ever going to be able to … What encore is ever going to follow that. He was a huge figure, I remember in school people would just get in arguments about him and he was ubiquitous. He was on commercials and he was just everywhere and he just seem like he’d been around forever. Of course as young kid as you realize his earlier career and how contentious it was. I think it starts and ends with this 100 megawatt personality, I mean, there’ve been great personalities in boxing before but there’s just nothing like this guy, I mean, you can watch stuff of his now on YouTube and he can still make you laugh.

When he came along I think it’s easy to forget now because we’re so used to athletes being showman and being boasters and braggarts and dressing outrageously and trying to draw attention to themselves is that before he came along athletes did not act like that for the most part. You look at old clips of old football or baseball and the guy hits a home run, they don’t pound their chest, they don’t point to the sky, they don’t pump their fist even, they just kind of cross home plate and shake hands and move on and boxing and football and all the sports were really like that. Ali came in, when he landed in the early 60s it really was like a visitor from another planet, it probably was a little bit like how people felt when Elvis Presley showed up on their TV screens in the 50s, “Who is this guy? Where did he come from?” He converged with what was about to happen in the culture that’s another key aspect of his career.

When he wins the title for the first time still known as Cassius Clay at that time, in February 1964, that’s the same month that The Beatles land in America and these two actually have a meeting. They have a photo op together. They’re seen by most of the press both of them Clay and The Beatles as just sort of flavors of the month. Clay is going to get his head handed to him by Sonny Liston the heavyweight champion and The Beatles are going to be popular for a month or two and then they’re going to vanish the way most of these things do. Of course, that doesn’t turn out to be case and they really turned out to be heralds of the youth culture that we all know about from the 60s. Ali came in at kind of the perfect time but he had such a huge impact because the sports had always been such a preserve of stoicism usually. Just talking about Joe Louis and Joe Louis was a great stoic publicly, he never gloat or boast or anything and Ali was really blowing that whole world apart and not everybody liked it.

Then the second thing of course is that he converges with the politics and that has two pieces. One is the racial politics and this is coming on right at the peak of the civil rights movement and he does not adapt the civil rights movement. He instead joins the Nation of Islam which actually rejects the civil rights movement and openly confronts whites as racist and in fact racially inferior to black. He really puts himself out on the edge with his politics and then he steps out even further when he refuses induction into the armed forces during these Vietnam years. Between the racial politics and the war politics, Ali by the late 60s although he’s looked upon today, people revere him and when he died he was celebrated. In the late 60s there are very few people in American life more divisive and more argued about than Muhammad Ali.

It’s a huge arch of his career that then comes full circle from the 70s and 80s when he becomes more popular and in certain ways the history helps him because American people turned against the Vietnam war in much larger numbers. People begin to look at him a little bit differently but his legacy on sports I think is probably those two pieces, one is it’s as relevant as the NFL National Anthem Protests. It’s bringing over politics and often tinged with racial concerns into sports and it’s the showmanship, it’s the kind of ego celebration. I should frank and say, you know I probably have a minority view on both of these things at this point in history because I think on balance a lot of this has not really worked out so positively. I don’t think that the political aspect of sports is working out, that great for people I think you see that in the NFL ratings, I think people want sports to be kind of a refuge from the world they don’t want it to be another ground in which we’re all fighting with one another.

I think it’s complicated. The second aspect about the showmanship it’s like a lot of originals, Ali could be just delightful as a showman but when you’ve got everybody acting like that it can be a bit tiresome and I find sports today with all the chest thumping and self-celebration to be a bit wearisome. I don’t really mean to lay that all at his door but he do get imitators and he certainly has had many imitators.

Brett McKay: This was like the 70s, 60s, 70s when he was fighting, his career eventually ended. Who do you think was the last great American heavyweight boxer? When can we say like okay the age of American heavyweights ended, who was that guy?

Paul Beston: In a peer of boxing sense I’d say the last great heavyweight was Larry Holmes who came right after Ali in the late 70s and was champion for much of the 80s but is largely forgotten today because he’s sandwiched between two giants Muhammad Ali and then Mike Tyson who followed him. Just on pure boxing because I think that Holmes accomplished more than Tyson’s boxing accomplishments while impressive it kind of fell short because his career kind of flamed out a lot earlier than people expected him. We weren’t quite able to see all that he might have been capable of, but in terms of the last great figure in terms like the way I wrote the book and then the figures that really reached out beyond the culture it’s certainly Tyson, Mike Tyson. He’s the end of the story more or less because there hasn’t been a figure since Tyson on the American side who’s had that kind of impact and that kind of sort of universal recognition.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and Tyson was the guy, the champion when I was a kid. I remember 87, I think it was like five or so like you were playing Mike Tyson Punch Out on Nintendo. I remember when the big fight was going on that summer, I pretend I was Mike Tyson, I remember I smacked my brother, my two year old brother in the face. I walloped him, I got in trouble for that but my brother was a bum, he was not a good fighter at two year old. What I didn’t know about Mike because now he’s sort of this, I don’t know, he’s sort of lampooned, right, today. He understands that and he plays these characters where people kind of poke fun at him but what I didn’t know about him was how … He was first a talent, he was strong, he was fast but he’s also very cerebral about his boxing like he would just sit and watch old films going back to the 30s and he would read about John L. Sullivan. He would try to imitate some of the great boxer like his haircut was inspired by Dempsey and he walked out like Dempsey without a robe on. Tell us a bit more of that side of Tyson that people don’t know about.

Paul Beston: I have always thought that that’s one of the really alluring and poetic aspects of Tyson’s story and I was a pretty big boxing fan by the time he came along in the 80s. I remember that even then because they would spotlight it when they would do stories on him and it’s kind of like the thing you’d script, it’s like, “Let’s make up a story about a boxer who’s not only great but he loves the history,” I mean, come on, that’s not going to happen. These guys don’t care about the history, they’re focused on their fights,” but Tyson really did, he really did watch these films. Of course, that’s largely because he spent from about the age of 13 on in the house of Cus D’Amato, a great trainer who trained not just Tyson but before him Floyd Patterson, a heavyweight champion.

D’Amato had French friends and associates with Jim Jacobs who was the great fight film collector who had the greatest collection of fight films in known possession and those have now been bought up by ESPN and that’s why you’re able to see them all. Back then you couldn’t just watch fight films, we didn’t have the internet, we didn’t have YouTube, it was hard to get them, he had them in his possession. This young kid was just wanted to know everything about boxing, there was a library of boxing books as well in the D’Amato house and Tyson was reading those books as well and not just about heavyweights but fighters from all divisions. When he became champion he started doing these little tributes that nobody would really notice except to someone who’s really, really a boxing gig. He would start mimicking poses that he had seen in these old 50, 60, 70 year old films.

One guy who knocked out an opponent and stood over him with his hands at his hips staring down at him and Tyson said, “I like that, I like that stance. I’m going to do that next time I knock a guy out,” and he did. He had this great reverence for the history and for the title that he was trying to get and it really added a kind of depth and weight to him which he already had because his story was pretty heroine story of his upbringing in Brownsville, Brooklyn and a broken home and life of crime as a very young boy. He had a lot going on but this element of history really did add some fascination to him. It made it seem as if he was destined to hold this title, this was all scripted, this is the person who should hold it. It did add a lot of luster to him.

Brett McKay: Yeah, like a lot of the other heavyweight champs from past decades, he was one of those characters that’s both celebrated and reviled. The guy had a really bad personal life, he went to jail for rape, had some other troubles as well. Again, that he’s continuing that trend of a boxer who we both simultaneously celebrate for their, I don’t know, manly virile Marshall ability but also the same time disdain.

Paul Beston: Yeah, for sure, I mean, I’m sorry, Tyson, I was going to say Sullivan, is because I’ve really been thinking lately about how parallel their career and life archs turned out to be because they really did whether it was drinking or Tyson was more of drug problem than just his personal demons. They really became notorious and the media made Tyson took it to a new level over the rape conviction. It was an awful episode and then when he got out of jail there was these other episodes with biting Evander Holyfield’s ear which is just even by boxing standards is an infamous, it was an infamous moment. You just saw him at the end of his career 12, 13 years ago, you just thought to yourself, “Well, I know how this story is going to end,” we know how the story is going to end and it’s not going to be pretty.

He, like Sullivan before him surprised us and showed that he had a different plan and he had another chapter to write and it’s really heartening to see it. He really turned his life around in really similar ways to Sullivan in fact they’ve even both one man shows, I mean, that’s what Sullivan was doing when he was giving his temperance lectures, he’s kind of telling the story of his life and how he reformed himself and that’s more or less what Tyson does in that one man show of his. It is an interesting parallel and interesting how it comes full circle. I’m sure Tyson would appreciate it too.

Brett McKay: Right, if he’s the last one, what do you think led to the demise of the heavyweight boxer being sort of this just giant in American culture? We’d mentioned like there’s the multiple governing bodies each lane claimed to being the holder of the heavyweight title, that was one facet but what else is going on?

Paul Beston: Several things, I mean, one is certainly the rise of other sports, that’s one factor, it’s not the whole story by any stretch but it’s certainly a part of it. As I was saying before in the real heyday of boxing really through the era of Joe Louis which takes you right to mid century. Boxing doesn’t have that much competition other than baseball and baseball is a national game, you don’t have to worry, that’s just is what it is. Besides baseball boxing didn’t really have any rivals and that began to change, the NFL really took off in the late 50s. The NBA would soon take off as well and other sports start to come in and then the rise of television came in which originally helped boxing a lot because it was very popular on television and people from a certain generation still remember it, the Friday Night Fights as they call them but boxing had so many different problems. It didn’t have any leadership, it didn’t have any commission or a coherent structure.

It had a terrible corruption problem including for a one period in particular massive mafia influence, it’s essentially run by the mob for the late 40s through most of the 50s and these things aren’t to catch up with it. Indictments, antitrust suits, the corruption of managers and promoters, deaths in the ring, there’s always a presence in boxing but it begins to bother people more than they did in the past including fights that are shown on TV where the fighters died. It’s kind of like the Vietnam effect that people talk about, Vietnam is the first war shown on TV that started to really alarm people and traumatize them in a way that other war had not. When the few of these things happen with boxing that became a real issue and also economically boxing among of all sports is the sport that draws from the lowest economic strata because it’s a very tough thing to do to be a fighter.

If you could be a baseball player instead or a basketball player or an attorney maybe that would be better. The stock of young men desperate enough to try this starts to be a little bit less robust than it was say 1900. Even though there’s still plenty of them, the standard of living in the United States from 1900 to now has multiplied several times over. Just a lot of different forces but the corruption and chaos of boxing’s organization really can’t be stressed enough and what we were talking about with the championships because with all the problems that sport had when you add the problem that nobody even knows who the champion is anymore. What is the reason that a casual fan wants to bother with this? It began to lose fans and finally for me because I live through this, it left television, it used to be on regular television and then the fights increasingly move to cable and then to pay-per-view and that was great for the fighters fighting in those bouts because they made a lot of money.

It wasn’t very good for getting the sport into the mainstream when you show up at work on Monday, Monday morning and talking at the coffee machine about what you watch that weekend, it wasn’t boxing because in the old days people would’ve seen that fight on Saturday afternoon on ABC and that was a big part of my growing up boxing was on Saturday afternoon almost all the time and they were big fights, championship fights and that’s how I found the sport. It kind of cordoned itself off into this premium pay model and along with its many other problems it just slowly kind of marginalize itself. Then we just didn’t have another American heavyweight who would come along, I think all of that probably could have been dealt with one way or the other if you had another Tyson come along because figures like that do capture people but the sport began to really decline in the United States in such a way that the heavyweights which had always been an American thing by the turn of the 21st century you woke up and all of sudden all the contenders were in Europe, most of them anyway.

These two brothers from Ukraine, the Klitschko brothers held the title for decade and a half between them before these new guys Anthony Joshua, the British fighters have now taken over. It’s kind of come full circle because boxing really starts … Modern boxing starts in Great Britain and now we’ve got the heavyweight title over in Great Britain again. Whether it can come back or not is hard to say but a lot of forces behind what happened to boxing and I should say not all of it was really boxing’s fault, I think some of it was inevitable.

Brett McKay: Right, I’m curious after you researched and wrote about these guys, I mean, boxers they’re sort of archetype of American manliness. Did you learn anything about being a man by studying these really complicated figures who both celebrated and reviled at the same time?

Paul Beston: Yeah, when I was writing the book, one question I tried to keep in my mind to see if I could answer was … That I thought might really anchor me in exploring these guys was, “What was it that drew me to them in the first place when I was a kid?” I mean you could draw into lots of things when you’re kid, why do they seize my imagination so much and really never let go, what was it about them or what was it about boxing. I think as best I can tell what it was and that relates to your question about manliness is that I think what got through to me as a kid that I didn’t realize consciously at the time was the experience of the boxing was such a solitary one. They have their support systems and their trainers and sparring partners and all that but at its heart the endeavor is a solo one and that’s really dramatized with that walk down the ring that I talked about and it’s dramatized by all your guys leaving you alone in the ring to face your opponent.

I think it was Joyce Carol Oates who wrote that the opponent is you, the opponent is you, it’s your reflection and there’s nowhere to hide. If you’re unprepared, it will show. If you’re not in physical shape, it will show. If you lose your fortitude at the moment of truth, it will show. There’s nowhere to hide behind a teammate. In other sports you can hope that Tom Brady will bail you out and he probably will but there’s nowhere to go in boxing, you’re left to your own resources. I think looking back as a kid it was the starkness of that confrontation which really got through to me. I remember as a kid feeling this knot in my stomach when I would watch the fighter walk up the aisle to the ring because I was putting myself in their shoes and thinking about what it must have felt like to face this test.

We all face our tests, we all face fears but most of us don’t have to face them in an arena full thousands of people in a contest where victory can bring glorification but failure could mean destruction or humiliation. I think it was the way they handle that, ultimately you can only face that kind of thing with courage which doesn’t mean not feeling fear, it means dealing with fear and with some form of stoicism and fighters really have to have that. Whatever else they did in their lives and however uneven the rest of their personal lives may have been, they kind of know the answer to the question about themselves that most of us outside of the military are probably still wondering about.

Brett McKay: Paul, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about your book?

Paul Beston: There’s a lot more information about the book on my website which is PaulBeston.com and it got a blog on there too where I write about other things about these guys and the best place to buy the book is on Amazon.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Paul Beston, thank you much for your team. It’s been a pleasure.

Paul Beston: Thank you, Brett.

Brett McKay: My guest, it was Paul Beston, he is the author of the book, “The Boxing Kings: When American Heavyweights Ruled the Ring.” It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can also find out more information about Paul’s work at PaulBeston.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/boxingkings where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic. Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice make sure you check out The Art of Manliness website at ArtOfManliness.com. If you enjoy the podcast, have got something out of it, I’d appreciate you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. If you’ve done that already, thank you so much. Please share the show with a friend or a family member who you think would also enjoy it. As always thank you for your continuous support and until next time. This is Brett McKay telling to stay manly.