If you’ve ever read the classic book Endurance, you probably shivered and shuddered as you wondered what it would have been like to have undertaken Ernest Shackleton’s famously arduous Antarctic rescue mission.

The adventurer Tim Jarvis did more than wonder. When Alexandra Shackleton challenged him to re-create her grandfather’s epic journey, he jumped at the chance to follow in the legendary explorer’s footsteps.

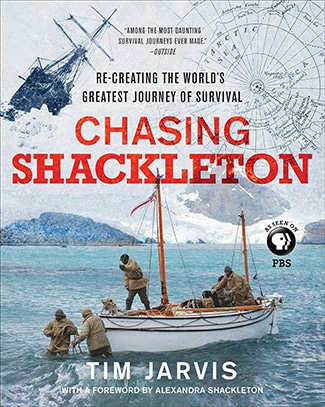

Today on the show, Tim, the author of Chasing Shackleton: Re-creating the World’s Greatest Journey of Survival, first shares the story of Shackleton’s heroic effort to save the crew of his failed Antarctic expedition. Tim then tells us how he and his own crew replicated Shackleton’s journey over land and sea, from taking the same kind of rowboat to eating the same kind of rations — and the lessons in resilience and leadership he learned along the way.

Resources Related to the Podcast

- Endurance by Alfred Lansing

- Shackleton’s apocryphal recruiting advertisement

- AoM Article: Leadership Lessons from Ernest Shackleton

- AoM Article: What They Left and What They Kept — What an Antarctic Expedition Can Teach You About What’s Truly Valuable

- AoM Article: Alone — Lessons on Solitude From an Antarctic Explorer

- AoM Article: The Libraries of Famous Men — Ernest Shackleton

Connect With Tim Jarvis

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. If you’ve ever read the classic book Endurance, you probably shivered and shuddered as you wonder what it would have been like to have undertaken Ernest Shackleton’s famously arduous Antarctic rescue mission. The adventure of Tim Jarvis did more than wonder when Alexandra Shackleton challenged him to recreate her grandfather’s epic journey he jumped at the chance to follow in the legendary explorer’s footsteps. Today on the show Tim the author of Chasing Shackleton, recreating the world’s greatest journey of survival first shares the story of Shackleton’s heroic effort to save the crew of his failed Antarctic expedition. Tim then tells us how he and his own crew replicated Shackleton’s journey over land and sea from taking the same kind of rowboat to eating the same kind of rations and the lessons and resilience and leadership he learned along the way after the show’s over check out our show notes at aom.is/Shackleton. All right, Tim Jarvis welcome to the show.

Tim Jarvis: Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: So you are an explorer and adventurer and in 2013 you did an expedition in which you recreated Ernest Shackleton’s famous rescue mission in the Antarctic. I’m sure a lot of people have read that famous book Endurance, we’re going to talk about that adventure today but before we do let’s talk about your background. How did you get started with exploring the Antarctic?

Tim Jarvis: Well look I mean I’ve always explored things ever since I was a kid. I grew up in Malaysia, as a young child my parents used to just send me outside and tell me to go and find things to do and that stayed with me all through childhood all the way into adulthood and the expeditions just got bigger and bigger and I think once you spend a bit of time in your own company and being that version of yourself, you feel most like yourself when you’re in those places so I’ve just kept on going and I guess that the ultimate conclusion is to end up doing Shackleton’s journey.

Brett McKay: Before you did Shackleton’s expedition you recreated the Douglas Mawson expedition. For those who aren’t familiar with that expedition, what was it and where did you get this idea to replicate it?

Tim Jarvis: Yeah look I mean I’ve done lots of expeditions in the modern way but I’ve done to the old way Mawson and Shackleton, and Mawson was an Australian scientist he was a contemporary of Shackleton. He’d gone on an expedition with two colleagues to chart an uncharted section of Antarctic coastline and essentially the first guy about 350 miles out from base fell in a crevasse he went down the hole with the dog team and the sled that contained about 80% of the food for the three men so once he was gone Mawson and the surviving guy were left with essentially a 330, 340-mile return trip back to base with only about 20% of the food they needed to survive, the second man died halfway home in Mawson’s arms of what he described at the time as fever but it could well have been… It could have been anything, it could have been malnutrition, hypothermia, frostbite, bit of gangrene but Mawson was the sole survivor of that expedition and many people had asked you know what is it that happened to the second man and did Mawson need to eat the second guy in order to make it and so I decided to do that trip the same way as Mawson with the same starvation calories he had to see what happened.

I just traveled with an increasingly nervous Russian guy we started from the point at which the first man died and the Russian guy and I, John basically tried to trek back to base the same distance as Mawson on the same food that he said he had without need to eat him and I made it, but I lost over 70 pounds in weight and fell over the finish line but I’m pretty much convinced that the thing that killed the second guy was eating the dog livers on that original expedition and he got vitaminosis that’s what killed him and that it could be done without the need to eat the second man so the prize was to be asked to do Shackleton’s journey.

Brett McKay: What’s vitaminosis what is that?

Tim Jarvis: That’s when you… Things like the livers of Arctic animals contain toxic levels of vitamin A and humans just cannot metabolize that, so if you eat the offal of those animals whether it’s a polar bear or a fox or a dog or a reindeer you are poisoning yourself. They didn’t realize that back in 1913 but that’s what was happening.

Brett McKay: So you mentioned you did some other expeditions the modern way what were some of those expeditions you’ve done in Antarctica?

Tim Jarvis: Well look I’ve been to Antarctica 13 times. I bid to be the first person across Antarctica one side to the other on foot unsupported I got about 2000 kilometers on that journey it was a pretty brutal trip the thing that prevented me doing the total crossing was a fuel leak into my food about three-quarters of the way through the journey but I did get the record for the longest journey at the time I got to the pole in 47 days and then out the other side. I’ve also been down and made a VR film called Thin Ice which is all about showing the amount of change that’s happening in Antarctica that required getting to some pretty remote places then of course there’s the Mawson expedition, there’s the research for the Mawson expedition then there’s Shackleton and the research for that, and I’ve been to the high Arctic five times so look I spend a lot of time down there.

Brett McKay: When you do these expeditions whether it’s a modern one or a recreation what’s the hardest part, is it the cold, is it the long distance you have to walk, the solitude? What’s been your experience?

Tim Jarvis: Look on any given day the difficulty changes I mean, sure you can have extreme weather, you can have monotony, you can have danger if you fall in crevasses which has happened before. I think it’s the relentlessness of the place that really does you in. I think the key thing with successful expeditions is just having your own internal frame, your own internal, a kind of way you’re gonna conduct yourself because you’ve got a place with 24-hour light, if you go in the summer you’ve got an endless white horizon you have to impose your own kind of structure on things and just agree to do what you set out to do, otherwise you can kind of get lost in the enormity of the place. So I think it’s the relentlessness, you can’t stop or you get cold, the only time you can stop is really when you get in the tent at the end of the day but even that has to be done as quickly as possible because you’re 10,000 feet up on the polar plateau and it’s minus 40 degrees so you’ve got to move fast, so I think it’s that relentlessness.

Brett McKay: Well let’s talk about Shackleton’s famous adventure when did Shackleton make what became his most famous Antarctic trip?

Tim Jarvis: Well Shackleton had done… He’d been south with Scott of course on his expedition in 1903, ’05 and he was invalided home actually from that. He then went a second time on the 1907, ’09 Nimrod expedition and he almost made it to the South Pole, so this was actually his third expedition the one that he’s really renowned for, was the third expedition and he went down on the eve of the First World War in 1914 and the goal was to cross Antarctica from one side to the other because of course Scott had made it to the pole sadly didn’t make it back, he and his team of four died. Amundsen a Norwegian of course made it in and out with no problem they were just slaughtering and consuming their dogs and feeding the weakest dogs to the strongest in order to make it but they did a very good job so Shackleton thought to do one better than what Scott and Amundsen had done he would go all the way across that was the basic plan and he left literally as First World War was breaking out.

Brett McKay: Okay when did things start going awry for the trip?

Tim Jarvis: Well I mean I think things went awry almost from the outset I mean they left the UK, he wrote to Churchill he was head of the Admiralty and said look give me the word and I’ll give over the whole, the ship the expedition resources the men, to the war effort and Churchill just said proceed it was a one-word response and things went wrong almost immediately they got down to Antarctic waters they reached South Georgia on the way down which is an island at 54 degrees south middle of the Atlantic at the bottom basically and they got down there and they realized that when they spoke to the whalers who were there they said look the ice is so thick this year you’re never gonna make it to Antarctica but unfortunately of course they had no choice but to keep going and they did and of course encountered the pack ice and the ship ground to a halt about 40 miles short of the Antarctic coastline where it remained until the pressure of the ice crushed the hull and the ship sank, so look it started going wrong from that moment.

Brett McKay: How long did it take for the ship to sink after it got packed in ice?

Tim Jarvis: Well they were stuck on the ship for 10 months and they were then once the ship had sunk they lived on the pack ice for a further five months so they had a year and three months either in the stricken ship or on the pack ice so that takes you through by that stage to 1916 unbelievably, they were at 1916 and when the pack ice broke up after they made camp on it they paddled for five days to reach this island called Elephant Island there everybody remained, he left 22 of his men there under two of the upturned row boats that they were in and he headed off in April 16 to do this crazy journey across the Southern Ocean to try and raise the alarm and rescue the guys he’d left behind.

Brett McKay: So give us an idea what did that journey look like so they dropped them off at Elephant Island where did he go after that?

Tim Jarvis: Well like I said the ice broke up they paddled for five days in three row boats they left two there with 22 men and then Shackleton and the five strongest got in the most seaworthy of the boats they took planks off the other two and made a kind of deck on the one they were going to take the James Cared and they headed off across the Southern Ocean the nearest inhabited place that you could reach was this island South Georgia where they visited on the way down there there were whaling stations the problem was it was 800 nautical miles away across the roughest ocean in the world and they only had a sextant to measure the angle to the sun or a star if they could see them and you miss the island either because you can’t find it or you sink in them on the way up there obviously that’s bad but if you miss it there’s no way you can turn around and have another go because the winds and currents that have pushed you north from Antarctica towards South Georgia won’t allow you to sail back to have a second go, so they had to get the trajectory right first time across this vastness of the Southern Ocean with mountainous seas and they experienced two storms and a hurricane on the way up there almost capsizing on multiple occasions before they made it.

Brett McKay: And then they make it and then they had to go on a hike after that.

Tim Jarvis: Well yeah that’s right I mean they arrived from the south and they celebrated because they found South Georgia but of course they arrived on the wrong side really they arrived on the southern side the southwestern side of the island and all the whaling stations where the people were were on the northern side so they couldn’t sail round because if you try and hug the coastline the same winds and currents that have pushed you north will just push your little rowboat onto the rocks and and you’ve got to understand that South Georgia is mountains 10,000 feet high really really jagged angular peaks like the Alps coming straight out of the ocean so the only thing for it was to climb through the uncharted interior and of course they had no equipment, they had no climbing ability they had no tent so it meant they couldn’t stop they had to keep moving they had pieces of congealed animal fat for their sustenance from the seals they killed on the ice and they pulled the nails out of their packing cases and pushed them back through the soles of their boots for grip because they didn’t have any crampons so it was a pretty serious undertaking to attempt this it was desperation but they had no choice.

Brett McKay: How long did the hike take to get to the whaling station?

Tim Jarvis: When Shackleton got to South Georgia they had the worst weather South Georgia can throw at you, so they were actually stuck on the beach where they landed for a further four or five days at which point Shackleton realized three of the guys he was with were just in such poor shape they weren’t going anywhere so he was already reduced to him and two others to try and make the crossing and the crossing then took 96 hours… Sorry, in their case 36 me it took 96, 36 hours of constant movement with no ability to rest for more than a few minutes at a time or you would freeze they had no shelter so by the time they reached the whaling station they’ve been out there for a long time.

Brett McKay: And then once he got to the whaling station Shackleton immediately started planning a rescue mission to get his men that he left on Elephant Island and when the ship finally got there this was almost two years after the endurance got stuck in the ice and all 22 of his men were still alive and the end result was Shackleton saved his entire crew I mean no one died correct?

Tim Jarvis: Yeah that’s right I mean he is really the almost the entire opposite of what happened to Scott. Scott died along with all his men very heroically in his bid to reach the South Pole and Shackleton equally heroically but for different reasons saved everybody on his failed attempt to cross Antarctica from one side the other he brought everybody home all 27 men and they got back in 1917 just in time to participate in the final years of the First World War.

Brett McKay: So what was Shackleton like as a leader what made him different from Scott and the other Antarctic explorers that allowed him to despite all the odds carry out successfully this rescue mission?

Tim Jarvis: Well Shackleton was a people person really he was an outsider he was Anglo-Irish which just meant that as far as the Irish were concerned he was a bit too English and the English regard him as sort of a bit too Irish and so he didn’t really sit comfortably in either camp he was merchant Navy rather than Scott who was Royal Navy so he couldn’t just rely on commanding people to do things like you can in the Royal Navy or you could back then, an officer issued an instruction you had to do it even if you didn’t agree with it whereas merchant Navy you had to really be liked by people though they wouldn’t do things for you and he had a lot of female influences in his life as a young man and that maybe made him a bit more emotionally intelligent than the equivalent male of that period would have been so all in all it basically made him the kind of person who was more compassionate, he was a tough guy but he was compassionate and he understood how to get the best out of people and it was all about putting yourself in their shoes and seeing things from their perspective and that allowed him to target the way he spoke to people to get the best out of people.

Brett McKay: And the other thing that stood out to me as you wrote this book and carried out your own expedition you also talked about how Shackleton he just had this unwavering optimism no matter the odds he’s like, Oh we’re gonna be fine like he was very intentional about it.

Tim Jarvis: Yeah he said optimism is true moral courage and he just had that fundamental optimistic outlook on life maybe it was his Irish genes, maybe it was his upbringing maybe it was just who he was as a person, but yeah absolutely he just had that incredible what we would now call growth mindset where if a problem came your way he just looked at it as an opportunity to prove himself and to overcome it and he rose to every challenge. Problems are just things to overcome after all I think he said and he just seemed to enjoy it, it was all part of the game and part of the test genuinely philosophical outlook on life.

Brett McKay: Okay, so you get this idea to replicate Shackleton’s journey and we’re going to talk about the lengths you went to to make sure you got it as close as possible, so you tried to make the same type of boat the same type of clothing the same type of gear that these guys would be using the same sorts of rations any expedition to the Antarctic is a huge undertaking, there’s so many moving parts there’s layers upon layers of bureaucracy that you have to go through just to make a trip happen, when you set your eyes on this goal to recreate Shackleton’s journey what was the first thing you had to work on?

Tim Jarvis: Well the first thing to do was to decide how we were going to do this. Were we going to do it? Absolutely true to the way he did it and once we decided we were that kind of made a lot of things in some respects easier because you just decided you were going to use a keelless rowboat, you just decided you were going to use non waterproof clothing you just decided you weren’t going to use you know GPS, you were going to use a sextant which meant learning how to traditionally navigate using one so we could make the same kind of mistakes they made because essentially we were copying them. So I think once you’ve made that decision in some respects, yes it makes life a hell of a lot more unpleasant for you but it makes the thinking bit a little bit easier because on expeditions you’re always trying to give yourself a bit of an angle and increase your chances of success but this time round we were just trying to copy what he had and let the cards fall as they may, so I’m not saying it was easy quite the opposite, you’ve got to rebuild all the boat and the equipment and learn traditional ways of doing things but at least you’re just copying what he did.

Brett McKay: The thing that stood out to me when you’re building the boat the hardest part was all the customs and the dealing with different countries laws on imports and exports and there were a few close calls where the boat almost didn’t make it to where it needed to get to launch this mission.

Tim Jarvis: Yeah look I mean it was almost five years of pretty torturous planning and stress to make it a reality which is I guess why no one had done it since Shackleton, and you’re right I mean the boat almost didn’t make it on many occasions I mean there are all sorts of issues with funding for a start but, and then you’ve got to find the expertise to do it, but I was leaving to go to France and I was getting on the… There’s a train tunnel that links to the UK and France and I was just about to put my car on that and go into zero phone reception and I got a call saying the boat is on a bigger ship about to do the same crossing as me but on the surface and the paperwork is not in order and I had to make frantic calls to Australia to get custom information and ownership details across to the port authorities and I had about two minutes to do it before my train left and I was plunged into half an hour of no phone reception had I not made that, the boat wouldn’t have got across to France we wouldn’t have made the ship that my little boat was going to piggyback on to go down to Antarctica and there wouldn’t have been an expedition.

And this sort of stuff was happening all the way through the whole process. When the boat finally got down to Antarctica ahead of us, it was traveling on a bigger ship and the bigger ship couldn’t get into the base that I’d spent two years lining up as the place that I would drop this boat off on at because the pack ice had moved in and again, within 24 hours I had to come up with an alternative plan, even though the previous plan had taken me two years to arrange. So yeah, look, it wasn’t without its stresses.

Brett McKay: You mentioned funding. How much did funding the trip take up your time and bandwidth?

Tim Jarvis: Look, funding always took up a lot of time. But I mean, you look back at the heroic era and frankly nothing was different back then either. I mean even Amundsen who’s regarded as being this kind of morally upstanding Norwegian who wouldn’t ever do anything wrong, I mean, he left owing money and just thought, you’ve just gotta go and do the expedition and we’ll make money if we’re successful. And it was the same for Shackleton and the same for many of them frankly. And it was to an extent the same for us. I mean, we obviously couldn’t leave owing money, but I certainly went with a lot of debt and we were lucky we had backers like Discovery Channel and PBS as the broadcast partners, but a lot of their funding, of course, went into the making of the film we made, not the funding of the expedition. So yeah, look, it took me years to raise the funds to make it a reality. I just tried to take a leaf outta Shackleton’s playbook and look at these things as problems to be overcome.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I like that idea that they’re just problems to over overcome. And I love the lessons that you can learn from Shackleton or even you trying to plan this trip. Maybe people aren’t listening to this show, aren’t gonna be planning a trip to the Antarctic, but we’ve all got these big projects that we have to do. Maybe we’re like renovating our house and same sort of thing. You’re gonna have these red tape obstacles, you’re gonna run outta money plans that you had, they’re gonna fall through. You just have to not stress out about it too much and just see them as problems to overcome. We’re gonna take a quick break for a word from our sponsors. And now back to the show. So planning the trip, going through the bureaucracy, funding the trip that consumed a lot of your time, but then you had to start recruiting for this trip. How did you recruit for your trip? And then did you get any lessons from Shackleton on how to recruit?

Tim Jarvis: Shackleton ran an advert that may or may not have been real. Certainly, he said it, whether it appeared as an advert, I’m not sure. But it said men wanted for hazardous journey, months of bitter cold, darkness, low wages, honor and recognition in case of success, safe return doubtful. And he got about 3000 applicants for the 27 places. Now, I thought about running the same advert. I didn’t in the end, the word got around. We were doing what we were doing and there were so many people who were interested that we were… We had about 300 applicants for the five places on board the boat. We weren’t gonna sink a perfectly good square rigor down in Antarctica and leave 22 people on Elephant Island. We were just gonna get in the keelless rowboat, the James Caird and do the rescue mission followed by the climbing.

And I had about 300 applicants. But I think what was so clever about what Shackleton said is the framing, the way he put it, he basically said, look, if you’re interested in a good time and coming and meeting new people and traveling to interesting places, perhaps don’t apply. But if you’re interested in doing something at the limits of your own personal endurance, then maybe this is for you because you’re gonna discover new things about yourself that will make your life far richer. Maybe not in monetary terms, but in spiritual terms. Then please sign here. And I think it appealed to people they thought, yeah, I’m up for that. Let’s see what happens.

Brett McKay: What sort of individuals were you looking for for your trip?

Tim Jarvis: Well I mean, and the very basic level, you’re looking for five people to accompany you. ‘Cause there’s six of us in total. You need people who can sail or climb or film or preferably a combination of all of those things. So the team were two real gun sailors. Nick Bubb, Paul Larson, Ed Wardle, who’s an Everest Mountaineer, who’s also the former free diving champion of the UK. So a single breath deep as you can go. He got down to almost 300 feet. Barry Gray, who’s my climbing partner, who’s former head of Outdoor survival for the UK Armed Forces. And Seb Coulthard who is a Royal Navy guy. Very good at technical stuff. So he really project-managed the construction of the boat. So you need all of those skills, climbing, boat building, filming, sailing, and navigating. But you also need more than that. You need what Malcolm Gladwell calls divergent intelligence. So you need people who have got the capacity to think laterally, be positive in difficult situations, and always be focused on getting a positive outcome. So you need problem-solving ability as well as the technical skills.

Brett McKay: So you’ve mentioned some of the period equipment and gear that you brought for your expedition. You used a sextant, the clothing you used was just like, it was basically cotton clothing that you… Did you like waterproof it with wax? Did you do any type of waterproofing on this stuff?

Tim Jarvis: Yeah, they’d waterproof. ’cause I mean, you’ve gotta remember that Antarctica is the driest, windiest, highest coldest continent in the world. But the emphasis on the driest is that some places there’s been no rainfall or snowfall for 200,000 years. It’s very, very dry. You’re not expecting to get rained on or snowed on, really. And so their clothing was breathable and windproof and so it was just tightly woven cotton. They were never intending to do an open boat journey in that clothing. So they used rendered-down fat from seals to sort of basically try and waterproof their clothing. And we used kind of an equivalent form of just organic grease really. So no animals were killed in the making of the film, but we did use kind of grease. We just wiped it on with our hands. And frankly after a couple of days, it had washed off anyway. And the clothing just wasn’t waterproof, but that’s what we did.

Brett McKay: So food, the original expedition, they killed some seals along the way. You can’t do that today. So what did you all do for food to get as close to the food that they ate as possible?

Tim Jarvis: Yeah, we were really, really very clinical about the way we went about working out the food, ’cause you got protein, fat, and carbs. And we really tried to get exactly the same proportions of those we remade the pemmican. Pemmican is the kind of sledging ration of the heroic era, which is basically very high-fat content food. We made pemmican exactly the same recipe as them. We took the equivalent meat that they would’ve got from the seals they ate in the form of… We took kangaroo jerky, which is very, very lean. And we worked out that it was exactly the same sort of fat content as the non-fat meat of the seals they consumed. And then we made up the rest of the fat load with more of the pemmican, which is essentially is just congealed lard anyway. So we took exactly the same stuff as they had. And we had the nigar and the nuts and the whiskey. We took exactly the same as they had. We were able to look at their rations very carefully and and recreate them.

Brett McKay: How many calories a day did you get for each man?

Tim Jarvis: Well I mean, bear in mind, even though their food was high fat and had lots of energy in it, they actually didn’t have much of it. ‘Cause of course they’d spent 10 months on the ship eating most of the food, and then five months on the pack ice once the ship sank before they did their five days to Elephant Island. And so they were using food up all the way through. So by the time they got to Elephant Island before they embarked on this journey, they didn’t have much left. So we were only on about two, and a half thousand calories a day, which is no more than you would have back home basically kind of ration that a fit male would probably consume back home. And it’s not really enough for the extreme cold you experience. And of course, you are getting wet the whole time, so your body is working very hard to keep warm and burning lots of calories. We probably needed 5000, but we were only eating about two, two and a half.

Brett McKay: Did you lose a lot of weight?

Tim Jarvis: Yeah, I lost weight. Not as much as on the Mawson expedition where I lost 70 pounds. I probably lost about 35 pounds on this trip because you’ve just got the stress of it all. You got the ever-present cold. We had one good day when the weather was, I wouldn’t call it warm, but it wasn’t cold. It was, the sun actually came out. But we got to South Georgia, we had five days of 100,120 mile-an-hour Katabatic winds and then crossing the mountains itself is a cold, unpleasant exercise. So yeah, you’re burning through the calories.

Brett McKay: So let’s talk about the trip itself. So it starts off on the boat. You guys created a replica of the boat that Shackleton and his crew used. You named yours the Alexandra Shackleton after the granddaughter of Shackleton and the patron of your trip. What was life like on that boat and like how much space did you have? I mean even like things like going to the bathroom, what was that like?

Tim Jarvis: Well, look, I mean everything’s challenging. I mean, you’re living in the space the size of a queen size double bed for six men basically. So there’s no lying down. You are sitting on top of rocks. Shackleton took a ton of rocks off the beach at Elephant Island to try and weigh the boat down and stop it tipping upside down in big sea in the absence of having a keel, the vertical that sticks out of the bottom of the boat to stop capsize happening. So you’re sitting on rocks and camera batteries to the equivalent weight is what he had. And you are sharing two steadily decomposing reindeer skin sleeping bags that people have been sick into. And you’ve got five of you just sitting there waiting for the guy who’s last in line to go up on deck and try and steer the boat.

At which point the guy who’s up there on the helm comes down and everybody moves around one if you know what I mean. Toilet was just done in a bucket, right kind of more or less in your face between one another. And you’ve got about half an inch of large planks separating you from the zero-degree Celsius sea water of the southern ocean. And it’s rough and noisy and dark and basically extremely unpleasant. So sometimes as terrible as it was to have to be on the helm trying to steer the boat, particularly at night with waves crashing over you with frozen… You were frozen solid. You sometimes look forward to the prospect of that rather than being stuck down below in a tiny, cramped seated position, sitting on top of the rocks. So look, it was not much fun.

Brett McKay: Was there a moment during that, the boat trip where you thought we’re not gonna make it, we’re gonna have to abandon this trip?

Tim Jarvis: Yeah, there are always those moments. The question is what do you do about ’em? To say that you don’t have that feeling pop up into your mind on multiple occasions during trips like this would be lying. I mean you do have those feelings, but we never seriously thought about stopping. But we did have near capsized situations at sea and very, very big sea state. We did find ourselves approaching South Georgia going pretty quickly ’cause we had massive seas pushing us onto South Georgia. And you’ve got a limited ability to steer and you’ve got boiling cauldrons of rocks just below the surface. You’ve got these vertical cliffs that go straight up into five, 6000-foot high peaks, even at the coast, massive intimidating place to try and land a keelless rowboat basically in big seas. And then crossing the mountains of South Georgia, we have multiple crevasse falls. So and no equipment really to get somebody out if one fell in and was injured. So yeah, there were many occasions where I thought this could be bad if we don’t get it right. But luckily we prevailed.

Brett McKay: So how long did it take you to get from Elephant Island to land?

Tim Jarvis: It was two weeks at sea followed by, yeah, five days when we got there. Pinned down by very bad weather.

Brett McKay: And how long did it take Shackleton?

Tim Jarvis: Well he in fact took 17 days. He took a few more days than us, but one of the reasons being they almost made it, and then a hurricane blew them offshore. They were tantalizingly close and they got pushed offshore and they had to wait till the sort of prevailing seas came back to allow them to get pushed back onto shore again. So they were lucky they didn’t get pushed out to sea and get pushed past South Georgia or as I say, they would never have been able to sail upwind to reach it again. They were lucky they just got pushed back in the direction they just come from.

Brett McKay: Okay, so two weeks onboard a boat where you have the space that’s about the size of a queen-sized bed that’s really cramped, that’s pretty tight, being around that many people. Did you guys have any personality clashes while you were on the boat? And if so, like how did you manage that?

Tim Jarvis: Yes, I mean there were the inevitable things, but what I would say is there are a good bunch of guys. We’d had many of those disagreements before we ever got on the boat, so I think the key thing with team dynamics on expeditions or in any walk of life is that you’ve gotta be honest with one another. And so we had some pretty frank discussions and disagreements before we ever got there. So, and that makes your relationship strong enough to withstand what comes with an expedition. There’s no point going down there, everybody being friendly and happy and avoiding disagreement for the sake of harmony, ’cause as soon as you get down there, you’re gonna find the pressure is on and things can fall apart. So look, we’d have plenty of disagreements and arguments and things like that. They’re all constructive though. And we were a pretty tight-knit group by the time we got there. That’s not to say you don’t have disagreements when you’re on board. I mean, it’s difficult when you’ve got someone’s backside in your face and you are cold and wet and hungry and you’re feeling sick and you’re worried about whether the boat will manage the next big wave that’s about to hit. Tempers get a bit frayed.

Brett McKay: Alright, so you get to land, that’s when you start having attrition. That’s when you have members starting to drop out. What caused the attrition?

Tim Jarvis: Basically it was people’s feet because you’re standing in leather boots with woolen socks often in knee to thigh, deep freezing seawater. So really for the most of the time on the boat, you’re not feeling your feet properly sometimes for an extended period of time, sometimes days. And for some of the guys that meant frostbite and what they called trench foot, which is what the soldiers used to get in the First World War, in the trenches, you’re just cold, wet in a seated position in their case. So you don’t get shot. In our case, there was just no space and your circulation goes in your feet. And so three of the six guys were unable to do the mounting crossing.

Brett McKay: But what’s interesting that attrition set you up so your trip, your hike, it would mirror Shackleton’s a bit more, correct?

Tim Jarvis: It was really amazing when you think that when Shackleton got there, two of his guys were in very poor shape and he left the third man to keep an eye on those two. He left them under the upturn boat on the beach that they arrived at. And then he and the two strongest did the crossing of the mountains. But he did it with Tom Crean, who was the tough guy on their expedition. And a guy called Frank Worsley who was the skipper and navigator. And when we got there, we were intending to do the crossing as a team of six. The idea was that the three sailors would put on modern gear, brought in by another small yacht, and then they would have modern comms and they would be our kind of backup. And me, Baz, and Ed, the three mountaineers would stay in the old gear and do the crossing.

That’s the way it was meant to be. But with injury, we ended up with me and Baz. Baz being the hard guy, me being the expedition leader. And we ended up with Paul, who was our navigator because the other guy’s feet were too bad and it was the same three as Shackleton, he did it together with Tom Crean, the tough guy, and Worsley the navigator. We did it as the expedition leader, the tough guy, and our navigator. So it was wonderful actually after you got over the initial shock of three guys dropping out, you thought actually this is a positive thing because it’s bringing us closer to what Shackleton went through.

Brett McKay: So you didn’t begin the hike right away. You actually, you were on the like the shore for a little bit, correct?

Tim Jarvis: Well, we had the worst weather South Georgia can throw at you for five days. So we just got pinned down. We couldn’t get away. We at that stage did have tents because we knew we couldn’t turn our boat upside down like Shackleton had done once he got there because we knew our boat ultimately had to be towed out of South Georgia and removed. You can’t just abandon boats down in Antarctica these days. So we knew we were gonna have to take it out. So we did concede and have some tents on the shore. They got blown away, got in really bad shape. We ended up hiding in a cave and getting driftwood and getting fires going in the cave just to sustain ourselves from the weather we were experiencing. It was pretty brutal.

Brett McKay: Did Shackleton have something similar where you he was camped out a bit before he started the hike?

Tim Jarvis: Yeah, Shackleton also ended up in a situation where he had to wait it out for a few days. For him it was for slightly different reasons they’d been forced to stop off a, what he called cave cove, which is a different spot in the same bay before he moved after a period of time there, they moved a bit closer to the head of the bay before they started their climb. But the amount of time that he had to wait and the amount of time we had to wait very similar again, we didn’t try and make that similarity happen, it just happened with the weather we were given.

Brett McKay: So you said earlier that South Georgia has a lot of high jagged peaks. What were the hiking conditions like?

Tim Jarvis: South Georgia is like an alpine mountaineering exercise. It’s very, very steep terrain. I would say the climbing up is actually not bad. It’s perfectly doable. The difficult bit is the going down and there are two serious descents you have to do if you follow exactly the footsteps he took. The first is off the Trident Mountains where you’re on the high ground and you’ve gotta kind of find a cool wall between these mountains that stick up out of that ice cap and you’ve gotta go down those to get to the lower ground. And that’s about a 1500-foot descent down very, very steep terrain. So that’s the first bit that’s tricky. The second thing that’s tricky is crossing through the glaciers where traversing is a major issue and you have to travel whether the weather is good or bad, you’ve gotta keep moving. And so we traveled even when we couldn’t see where we were going.

And you know, that means you fall in crevasses, you don’t even see. And the third thing is break Wind ridge, which is the final ridge going down into the valley just before the whaling station. That’s about a 1000-foot down climb. And that is the most dangerous bit of all certainly the steepest and if you follow Shackleton’s diary, that’s what he did. And so that’s what we did. And it was pretty challenging ’cause if anybody falls, you just pull the other two guys off with you and you fall to your death. So it was tricky and we were very, very pleased when we got to the whaling station, I can tell you.

Brett McKay: And so it took you guys 96 hours, correct?

Tim Jarvis: It took 96, yeah. I mean one of the reasons for that was we were actually joined also by a yacht that had come in. We had a beacon on our boat that showed this other yacht who weren’t with us but could see us in the Southern Ocean. They could see when we were approaching South Georgia. And so they too made their way to South Georgia and then it brought with it two camera guys who had a lot of mountaineering experience. And the idea was they would be in modern gear and they would accompany us to film what happened on the mountain crossing. Basically, they decided they couldn’t do the crossing. The weather was too extreme. One guy had a kind of injury, the other guy decided it wasn’t for him, too extreme. And so both of those guys were out. So part of our 96 hours related to having to kind of stay with those guys and try and make sure they got down safely in the end, they had to make their own way down, but we still had to stick it out with them on the high ground for about 36 hours. So that accounts for 36 hours. But I’m not quite sure where the other day came from that it took us compared to Shackleton. It was amazing the speed that he crossed that terrain.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it seemed like the TV crew got on your nerves quite a bit. It seemed like there were necessary evil sometimes.

Tim Jarvis: Yeah, that’s right. That’s right. I mean, Shackleton never had to put up with that sort of shit. I said to myself, excuse the language. I mean, and it’s true when he was there, it was just him and the enormity of the landscape through which he traveled and the pressure he felt to make sure that somebody made it to raise the alarm to go back and rescue the guys he left in Antarctica for us, we were burdened by the film guys, for them it was a job really, for us it was a vocation, it was a calling and that’s the difference. None of my guys got paid, me included, and we were there ’cause of the love of it. Whereas I think if you’ve got people who are there because they’re doing a job as good as they might be, it makes their kind of decision matrix a little bit different to yours. And that’s what happened.

Brett McKay: Did you suffer any injuries on the hike in the climb?

Tim Jarvis: Well, I mean, I’ve already had bad frostbite of my hand. Haven’t lost any fingers, but I certainly lost sensation, permanent nerve damage in nose. And same with my right foot. And that same old injury flared up again, but I wasn’t about to tell anybody because I just don’t think it really helps. But no, apart from that, we made it through unscathed lost weight, had a few crevasse falls, as I say, more than a few crevasse falls, but luckily none of them were serious.

Brett McKay: But the title of the last chapter of the book comes from a line from Shackleton. He said, never for me, the lowered banner. Never the last endeavor. What did that line mean to you after you completed this journey?

Tim Jarvis: It meant that for me there was always another challenge. It’s not in life as though you retire from something. It was a calling for him. It is for me, there’s never gonna be a last thing until it’s the last thing and then it’ll be beyond your control to do anything about it. There’s always gonna be something you’re gonna take on. And for me, I guess I’ve remained consistent to that throughout my life. I’ve got a lot of energy. I can’t imagine just stopping, why would you? For him, there was always the next thing. And so, in his case, he went back down six years after the expedition that in many people’s eyes was his greatest victory. Yes, he didn’t make the crossing of Antarctica, but he did save everybody and demonstrated this incredible leadership and heroism into the bargain. And he went back one more time and died of a heart attack back at the scene of his greatest victory back at South Georgia the night he arrived. And so that was the final chapter for him, but he was kind of… He went down fighting.

Brett McKay: What have you been doing since this expedition?

Tim Jarvis: Oh, look, since the expedition, I’ve had a project called 25zero, which involves climbing all the mountains at the equator that have a remnant glacier to highlight climate change. And I’ve got through 16 of them and then COVID sort of got in the way and I’ve been working on that. I’ve made a film called Thin Ice, which is a VR experience about Shackleton design really for kids, but more grown-up kids seem to like it than kids, or at least both like it. I’m working with the Australian government on setting up marine protected areas down in the southern Ocean. And we had a big success last year with Macquarie Island, which is one of Australia’s three sub-Antarctic islands now has a big sanctuary of almost half a million square kilometers around it. Lots of things I’m working on. I’ve got a reforestation project I’m working on called the ForkTree Project. I continue to make films, I continue to do trips and I continue to work on the environment stuff. And as far as I’m concerned, they’re kind of all interconnected. Makes sense to me anyway.

Brett McKay: So never the lowered banner for you.

Tim Jarvis: Never the lowered banner. Never the last endeavor.

Brett McKay: That’s right. Well, Tim, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Tim Jarvis: So look, I think the best place to go is probably my website, timjarvis.org. They can go to thinicevr.com and they can go to theforktreeproject.com, which is my reforestation work. And then of course there’s social media Tim Jarvis AM as in Am like the morning, and that’s on LinkedIn and Instagram.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Tim Jarvis, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Tim Jarvis: Thank you, Brett. It’s been wonderful.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Tim Jarvis. He’s the author of the book Chasing Shackleton. It’s available on amazon.com. You can find more information about his work at his website, timjarvis.org. Also, check at our show notes at aom.is/shackleton, find links to resources and we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AoM podcast. Make sure to check out our [email protected] where you find our podcast archives. And while you’re there, sign up for our newsletter. We got a daily option and a weekly option. They’re both free. It’s the best way to stay on top of what’s going on at AoM. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it. If you take one minute to get your review off a podcast or Spotify, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support, and until next time, it’s Brett McKay reminding you to listen to AoM podcast but put what you’ve heard into action.