In the first year of his presidency, the press used Theodore Roosvelt’s name in connection with the word “strenuous” over 10,000 times. He was known as “the strenuous president,” and with good reason: from his youth, TR had lived and preached a life of vigorous engagement and plenty of physical activity.

Today on the show Ryan Swanson, professor of sports history and author of The Strenuous Life: Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of the American Athlete, discusses not only how TR was shaped by what was called “the strenuous age,” but how he shaped it in turn by promoting sports, and participating in athletics himself. We begin our discussion with what was going on during the late 19th century that got people interested in what was then called “physical culture.” We then turn to the beginning of Roosevelt’s introduction to vigorous exercise as a boy, and how he famously decided to make his body. We discuss TR’s fitness routine when he went to Harvard, and how his becoming a fan of football there led to him supporting the preservation of the game as president. We then discuss how TR lived the strenuous life while in the White House, and thereby inspired the American public to live vigorously too. We take a fun look at what TR thought of the game of baseball, how he went to a health farm at age 58 to get back in fighting shape, and what kind of exercise and athletics TR would be into if he were alive today.

Show Highlights

- The culture and society Theodore Roosevelt grew up in

- How folks would “cleanse” themselves in the early 20th century

- TR’s origin story — how he turned his sickly body into a vigorous machine

- Roosevelt’s college experience at Harvard (and how it turned him onto athletics)

- The “renaissance man” nature of TR

- Roosevelt role is saving football

- TR’s “Tennis Cabinet” and how he got important people to partake in vigorous activities

- How TR’s lifestyle influenced the broader public

- Why didn’t TR like baseball?

- TR’s farm experience near the end of his life

- Roosevelt’s lasting legacy on sports in America

- What sorts of sports and physical fitness would TR be into today?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Theodore Roosevelt, Writer and Reader

- The Secret of Theodore Roosevelt’s Greatness

- Theodore Roosevelt on Citizenship

- The Field Notes of Theodore Roosevelt

- Theodore Roosevelt’s Advice on Reading

- The Fists of Theodore Roosevelt

- Theodore Roosevelt’s Reading List

- AoM Comic — I’ll Make My Body!

- How Theodore Roosevelt Saved Football

- The History of Physical Fitness

- Neurasthenia

- A Call for a New Strenuous Age

- William Banting

- Tips and Inspiration on Being a Well-Rounded Man

- “The Strenuous Life” speech

- LetTeddyWin.com

- Take the TR/JFK 50-Mile Challenge

- The Strenuous Life

- Ryan Swanson’s website

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Bayer creates medicine to treat allergy symptoms, so allergies don’t get in the way of a good time. At Bayer, this is why we science.

Saxx Underwear. Game changing underwear, with men’s anatomy in mind. Visit saxxunderwear.com/aom and get 10% off plus FREE shipping.

Thursday Boots. A bootstrapped startup that handcrafts boots and sells them direct to consumer. The highest quality at honest prices. Visit ThursdayBoots.com, use code “manliness” to get free 2-day shipping, and while you’re there, check out my favorite, the Vanguard.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. In the first year of his presidency, the press used Theodore Roosevelt’s name in connection with the word strenuous up to 10,000 times. He was known as the strenuous president, and with good reason. In his youth, TR lived and preached his life with vigorous engagement, and plenty of physical activity. Today on the show, Ryan Swanson, Professor of Sports History and the author of The Strenuous Life, Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of the American Athlete discusses not only how TR was shaped by what was called the strenuous age, but how he shaped and in turn by promoting sports and participating in athletics himself.

We begin our discussion with what was going on during the late 19th century that got people interested in what was then called physical culture. We then turn to the beginning of Roosevelt’s introduction to vigorous exercise as a boy, and how he famously decided to make his body. We discuss TR’s fitness routine when he went to Harvard, how he became a fan of football there, which led to him supporting the preservation of the sport while he was president.

We then discuss how TR lived a strenuous life while at the White House and thereby inspired the American public to live vigorously too. And then we take a fun look at what TR thought of baseball, how he went to a health farm at the age of 58 to get back in fighting shape, and what kind of exercise and athletics TR would be into if he were alive today.

After the show’s over, check the show notes at aom.is/strenuouspresident. Ryan joins me now via clearcast.io. All right. Ryan Swanson, welcome to the show.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah, thanks. Glad to be here.

Brett McKay: So, you are a Professor of History at the University of New Mexico, and you’ve got a book out called The Strenuous life, Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of the American Athlete. Let’s start off by talking about the culture Theodore Roosevelt grew up in, because I think that explains or helps explain why there was a rise in interest in athletics in society as a whole during his lifetime and why TR’s idea of the strenuous life would resonate so much with the public. So what was happening in the late 19th century that helped birth an interest in what they called physical culture?

Ryan Swanson: Yeah. It’s a really dynamic time. If you look at the late 19th century, early 20th century, it’s a really dynamic time in US history. And it’s tough to boil down. There’s a lot of things going on, but if I were to point to two things, I would point to the fact that industrialization and urbanization are peaking in terms of their influence in American society. So, translating those, not to complicated words, but translating nonetheless, I’m a professor after all. More and more people are taking jobs working for somebody else. They’re being employees of factories in many cases, rather than working on a piece of land with their family, as families had done for generations. So, people are working in different ways.

And then in terms of urbanization, it’s at this point in American history about the turn of the 20th century, when more than half of the population now resides in cities. And these cities are fascinating places with lots going on, but they’re also really dirty and crowded and dangerous. And so life has fundamentally changed for the ways that Americans live. And so with all of that going on, there are benefits.

I don’t know about you, but when I think of technology, my mind tends to just go towards positive. New technology means a positive, generally speaking. But if we look at the technology of the 20th century, yes things are mechanized and consumer goods are cheaper, but there’s also a lot of negatives that come with that. These dirty cities, these cramped living quarters, people have to live close to where they work because the automobile is still a couple decades away from being wide spread.

So there’s also during this time of industrialization, urbanization, a rise in general sickness. People are doing to the doctor and they don’t have acute pain, but they go to the doctor and they’re confused about what’s going on. They’ll report things like bloating or fatigue or loss of sexual desire or balding or all of these factors, and there’s a general confusion. People look around and think, “Wait, you have all this progress, and all this change, why is it then that myself and the people around me seem to be less healthy and less vibrant than they used to be?”

So there’s this general concern about these changes going on. So, sports become part of the way of addressing that. This idea that with all this change, maybe I’m losing some of the core activities and realities in terms of what it means to actually be a fully functioning human. So, rise in cities, rise in mechanization, rise in industrialization leads to this concern about health, and so those are some of the things that are going on here at the turn of the century as Roosevelt is both growing up and then moving towards the presidency.

Brett McKay: So there’s a legitimate uptick of sickness and general feeling of malaise going on, but you also highlighted that there were all these articles written during this time talking about the good ole days when men were men back in 1800. And here we are in 1895, we’re weak, we don’t have what it takes anymore, which is funny because that’s the same kind of thing you hear today. That with the rise in technology and convenience, men aren’t as manly or vigorous anymore. So was there a romanticize for the past going on that magnified the problem?

Ryan Swanson: I think so. Absolutely. We’re seeing a combination, or they’re seeing a combination at that time of real issue arising, but also yes a really intense case of nostalgia for the way that life used to be. And the newspapers publish articles in magazines and pamphlets and speakers are going around the country talking about how this nameless example from the 1860s, The Civil War is over and what do men do, they come back from fighting a war, which had been glorious in and of itself, it’s often times portrayed, and then they’re working the land and they’re working alongside their father and they are digging holes and they’re raising crops and they are strong physically, and when their head hits the pillow at the end of the day, they sleep contentedly because they’ve been physically challenged and they’re living the way you’re supposed to live.

So yes, there’s tons of these stories going around about how men are no longer men, because they’re not working the land the same way that they used to. They don’t have the same power over their own lives is often times the narrative too. You’re working for somebody else now. We’re all employees. And I think these are absolutely analogous to some of the things that you’re hearing about society today, and about men today. The idea of toxic masculinity is being much discussed now. We didn’t have that at the turn of the century, but there’s more so this idea that there’s tainted masculinity, what men used to be has been lost with all this so-called progress and technology. So, all that’s creating this brew of angst and opportunity and desires for change.

Brett McKay: And in some of those responses in the physical fitness world, the physical culture world was very similar to some of the things you see today in response some of the concerns people have. So back in the 1890s, you saw the rise of these sanitariums, where people would go and just spend time on a farm and be in nature and walk and hike and do all these things, and it’s similar to what you see today. People would go outside and I’m going to be paleo so I can get back to my roots, they were doing the same thing in 1895, too.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah. To put it in our vernacular, they’re all about the cleanse back then. We’re going to go to a place that isn’t polluted by the toxins of the city. We’re going to eat things that come from the land. There’s even almost an anti-carb movement that goes on at this time. Let’s get back to meats and vegetables.

Brett McKay: Banting, that’s what they called it.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. It’s very analogous. If you do the Whole 30 or the paleo diet today, in some ways you are echoing just what Roosevelt’s time was doing in the ways that they understood. The medicine was a little bit different, but there’s this intense understanding that I am not functioning as well as I could, and I need to change something. And in separating from the city and my job and getting back to nature and getting back to a simplest way of eating, all those things are very popular. Some of the things you read from the time of Roosevelt as this revolution is going on in athletics, could absolutely be written today. The ideas are still pretty similar.

Brett McKay: So there’s some nostalgia going on, but people are also grappling with real mental and physical health problems that came along with urbanization and industrialization. And part of the response to this is to get into physical culture, to exercise, to eat better, to go outside, and this is the world that Teddy Roosevelt came of age in was shaped by.

But he himself also shaped this culture of physical vigorous activity that would become known as the strenuous life. And that’s because he had a personal experience with the difference that pushing back against softness could make. So let’s talk about the origin story of where his idea of the strenuous life came from, which is the story of how he turned his sickly, asthmatic boy body into a strenuous vigorous machine. So, tell us that story.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah, it’s a great story, and Roosevelt loves to tell it and I’m sure some of your listeners know it, but it bears repeating, because it really shapes the way Roosevelt thinks about sports. So, I’ll give you the snapshot version, but Theodore Roosevelt is an amazing child in a number of ways. He’s really smart. He reads a ton of books. He’s got a real scientific mind, and he’s always categorizing things and looking for the Latin name of this animal or that animal. So he’s very precocious, as you might expect from the man he goes on to be.

But his real Achilles heel from about age three until his early teen years is asthma, as you say. He has a terrible case of asthma. And I always urge my students, for example, or other people, to separate Roosevelt’s experience with asthma from perhaps the kid that you knew when you were back in elementary school, who yes had asthma, but had his inhaler but had to maybe sit on the side during PE class. And I’m not minimizing that experience, but for Roosevelt is this crisis. It’s a tragedy that’s taking place on a daily basis, and it absolutely defines his childhood. So, the family is not able to put him in school. He can’t handle school because he’s got these breathing attacks. They try all sorts of crazy remedies to get him cured.

They tried bloodletting, they have a seven year old Roosevelt smoking cigars. The family will go out for rides in the January icy air to try to get his lungs to open. They have him do shock therapy. Unfortunately albuterol inhalers, which become a real step forward aren’t invented until the 1950s. So Roosevelt is just dealing with this asthma on a daily basis, and it disconnects him from his friends. It really keeps him from living any sort of strenuous life as a child.

So he’s just a boy with a brain who’s a precious thinker, but he can’t act like most kids do. So Roosevelt tells this story over and over as an adult. And he’ll point to one pivotal moment. So he struggles, like I said, from about age three until his early teen years with this terrible asthma, and then things hit a crisis point. This struggle that Roosevelt was having put a huge strain on the family. Basically, they’re revolving around Roosevelt, and always trying to stop this next attack from happening. So Roosevelt’s father when Roosevelt is about 13, calls him in for a talk and basically says, we’re done.

And as a father, I certainly think about this, he basically says to Roosevelt, “You’ve got to fix this problem on your own.” And that doesn’t strike me as being particularly fair. Fix your own asthma. But, basically what Roosevelt’s father says is, he expressed his pride in his son. He says, “You’re smart, I’m proud of you,” and he says, to paraphrase, “You got the mind,” and Roosevelt clearly does, “but you’ve got to make your body.”

So Roosevelt takes this challenge, and his sister is actually in the room too, so she’ll tell versions of this story as well. He takes this challenge. He stops for a moment and thinks about it and then according to both of them, he throws his head back and says, “I will do it. I’ll meet your challenge, I’ll make my body.”

So Roosevelt from there going forward really dedicates himself to physical culture and exercise and he does it in a way that the best rich kid could, he has his father build him a mini gymnasium in the home, and then he goes to work training under several professional boxers who are former champions. And something really amazing happens. Basically, Roosevelt’s asthma goes away. Now, it never completely goes away. He’ll struggle with it off and on throughout the rest of his life but it ceases to be this tragedy or this crisis in his life. It becomes more controllable. And Roosevelt understands this as a causal relationship. I exercised, and I pushed myself, therefore I cured myself, and my asthma has gone away.

And I think in all fairness, I would understand it the same way. If I had some real big problem in my life, and I set forth a dedicated plan to solve that problem and that problem went away, I would say that’s what happened here. I did it. We know that it’s pretty common now for kids to age out of the worst effects of asthma as they hit their teen years, and this probably what happens to Roosevelt. It’s not this vigorous boxing, it’s not this exercise, which cures him. Now that helps, but it’s not as simple as Roosevelt understands it to be.

And so Roosevelt, for the rest of his life though will understand this relationship to exist. Push yourself and you will develop. And he’ll hold himself to this idea and as I think more significantly, he’ll hold the nation to the same idea. If we are weak, we should push ourselves, and we will get stronger. So, it’s a rally fascinating story about Roosevelt. And I think one other way to think about Roosevelt, the asthmatic sickly child, it’s the only version of up by your boot straps that Roosevelt can tell about himself. He comes from a rich family with political connections. So, he’s not like Lincoln who can say I’m a self-made man. The only way Roosevelt can really think of himself as a self-made man is in the context of athletics. So, perhaps that’s why he loves to tell people about how sickly he was as a child, once he’s moved past it.

Brett McKay: That story is great. I love that story, and I have been to his little home gym. I went to his house in New York. It’s really cool. It’s not huge but it’s this little room, I think it was a porch or a patio they turned into Indian clubs, medicine balls and the parallel bars. And you can go see that stuff. It’s still there.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah. It’s absolutely worth seeing. I’ve been there as well, and I think it really shows you a physical manifestation of this challenge that Roosevelt undertook.

Brett McKay: And even as a boy, he became known as this president who this vigorous energy and did everything full bore. He did that as boy, and you highlight in the book, he was a meticulous record keeper about his fitness, and you have a picture from 1875, he’d always measure himself, his chest, his waist, his biceps and just kept details about that, whether he beat his brother or not in running. Even as a 13, 14 year old boy, he was a little 25 year old life hacker.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah, that’s a good way to put it. I think, actually I really got some joy out of that part of the story. It’s funny. Roosevelt is self-absorbed as many teenagers are, right? So, he’s meticulously writing down the measurements of his biceps and his chest and am I getting stronger, but the best part is yeah, the older brother competing against his younger brother, and his younger cousins and when he wins he writes it down in this very fastidious official fashion. I don’t know something about this just speaks to me as a middle child as, “You know, look what these older brothers do.” So he’s obviously an amazing intellect and mind, and so when he engages in athletics, he does it in ar lately unique way, a really serious way to a certain extent and keeps all these record. So, that athletic diary that he keeps is a real treasure, I think.

Brett McKay: So, in high school, he starts building his body, asthma starts going away. He goes to college, goes to Harvard, which at the time was a hot bed for early sports in America. Nowadays, you don’t really think of sports and Harvard, but then that’s where sports were happening. What was TR’s athletic career like in college? And what was he like in college?

Ryan Swanson: Roosevelt maybe as much as anything at Harvard is a joiner. He joins every club that will take him. And in our vernacular today, I’d to says he’s got a case of FOMO. Fear of missing out. And this makes sense, given what he had experienced as a child where he’s cut off from opportunity, so he joins all these clubs. He goes in full bore but he does it in a way, which actually shows a lot of confidence. He’s not afraid of being different, and so there’s some really great memories of him in the gym at Harvard and what a unique looking character he was.

One guy remembers meeting Roosevelt for the first time and he basically paints this picture of Roosevelt is over in the corner and he’s got these high red stockings on which look really weird and he’s jumping rope and then he’s working in the parallel bars and he’s pushing himself to the ridiculous point of exertion. So this gentleman talks about Roosevelt goes crazy, and he’s out of breath and he’s basically collapsing and he falls don next to him and says, “Hey. I’m Roosevelt. Who are you?” And introduces himself like that.

So he’s a real character, not afraid to be unique, not afraid to be different. But during his time at Harvard, continue to really push athletically. So Roosevelt will commit his freshman year to visiting the boxing gym five days a week, he says. So he goes every afternoon, he pushes himself, he spars with any number of people he can get to compete against himself and of course, he continues to keep notes. “I beat this person, I lost to this person, I did these things.”

His experience at Harvard, he’s finally at the point where he can compete. He’s not a champion by any means. He’s not a brilliant boxer, but for Roosevelt the fact that he can be on a level playing field and he can go after athletics is a huge move forward, and he really embraces it. It becomes part of his development there at Harvard. He has ridiculously high standards for the kind of men he wants to associate with. He talks about finding a couple of friends at Harvard who were willing to box and wrestle for a couple of hours until about one in the morning, and that he really liked them because then they were willing to let him read some Alfred Lord Tennyson to them for a couple of hours after that.

So think about the standards here. He wants a guy who can wrestle and box and then listen to Tennyson and talk about it in to the wee hours of the morning. So he’s just a unique guy who’s curious and passionate and vigorous and joining everything he can get. He’s doing so at Harvard as you said. Harvard is big time athletics at this point. I don’t know what you would think of as the biggest athletic schools today. I don’t know, Alabama, University of Texas, USC-

Brett McKay: OU.

Ryan Swanson: That’s right. Boomer Sooner. Yeah right, so we think of those as the big athletic schools and as you said, we don’t put Harvard in there, right? Because Harvard doesn’t even offer athletic scholarships today. But during Roosevelt’s era, as he’s experiencing all these athletic things really for the first time, he’s at the big time athletic school. Harvard is the football school. They’ve got an amazing crew team. They win lots of baseball games. So they are the OU of this time, this marquee athletic program. And Roosevelt just to be clear, Roosevelt is nowhere near good enough to play for any of the Harvard teams. But he goes to games and he goes to the boxing gym, and he writes for the Harvard Crimson about athletics and so he’s in this real hot bed of athletics as he’s at Harvard during 1876 to 1880. So, it’s a really interesting time in his life.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about football a bit, which back then was much rougher, more violent sport than it is today. Even though Roosevelt didn’t play for the Harvard team, he’s a big fan of the sport, and remains a fan throughout his presidency.

Ryan Swanson: Absolutely. He’s a fan of football, no doubt about it. He admires the game for a number of reasons. If you think about the Roosevelt picture I’ve been trying to paint a little bit here, Roosevelt appreciates football as a tactical game. Although we’re talking about a cluster of people moving, to organize a group of men to gain territory and to push the ball takes strategy and takes tactics, so he really admires the game for that. He also admires it though on a much simpler level. He thinks it’s good that the sport is violent. He thinks it’s good that people get hurt, and that you test yourself and that you learn how to deal with an injury.

For Roosevelt, football is connected to war and to military, and so he sees that as a real positive. Not that he doesn’t have concerns about the game, but he’s always a fan. He always enjoys it and he always sees it as important as well.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And I think a lot of people at the time thought football is a great way to train young men for war, later on if they have to go to war.

Ryan Swanson: Absolutely. I’m not sure they articulated necessarily what they thought was coming out of it, but if you look at for example when he’s raising the Rough Rider regiment in 1897, 1898, Roosevelt’s able to organize the kind of man that he wants to get for this regiment, and he basically seeks out two types of people. He seeks out people from the Southwest. You know, I’m from New Mexico, we’re tougher I guess. He says he wants people from this frontier region of the country at that time, who are making their own way, they’re tough, they’re outside the normal system, and then the second category he’s looking for are college football players, college athletes. So Roosevelt sees them as ready for war, because they know how to work as a unit, because they know how to suffer together, so he absolutely makes this military football connection, which is, as I know you know, still a connection which exists in our general definition of football today.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I remember when I played football. You got the war pep talk that your coach would give you, pumps you up. I get it. So TR was a fan but there’s this point in his presidency, shortly after he became President, there was this crisis in football in college sports where people were about to get rid of football. Presidents were like, “We’re tired of it, it’s corrupting our students, people are dying,” and then Teddy Roosevelt as President of the United states thought it will be, “No, I’m going to make this a priority as part of my agenda to save football”. What did that look like?

Ryan Swanson: Yeah. So I would make the argument Roosevelt doesn’t save football, because no one person could save football, but as you’re saying, he does play a really important role in the moving forward of football. So to set the scene a little bit, if you get to 1905, Roosevelt has just been re-elected President. He’s very popular. He’s got a lot of political capital to work with, and at the same time in 1905, his oldest son Ted, Jr. is playing football at Harvard, so he’s a football parent that at time, which I think, is always important for Roosevelt. He sees the world, yes as a President, and yes as an intellectual, but he also sees it very much as a father of kids who are playing sports.

So in 1905, the violence that’s always been part of football climaxes, or probably the opposite since it’s a bad thing but in 1905, depending who you ask, 18, 19, 20 young men die on the football field, because of football injuries. So at that time, the abolition movement that exists, there’s a movement very much arguing that football should go away, they’ve got all the material that they need. So they seize on these injuries, and really push to get rid of football, especially as it connected to educational institutions.

So the guy really the forefront of this movement, ironically is Charles Elliot who’s the President of Harvard. And Elliot has always disliked the violence of football. He thinks it takes away from the educational mission of the school and looking at all this, the deaths that are happening, Elliot pushes for Harvard to get rid of football, which would be a huge injury to the sort as a whole. So, I don’t know who off the top of my head the President of Oklahoma is but imagine if he came out said, “We’re getting rid of football.” I can’t really think of that happening, but it would be a huge deal, right?

So that’s who’s leading the abolition of football movement and so because of that, Roosevelt gets pulled into this debate over where the game is going. And so Roosevelt has just won the Nobel Peace Prize, so he’s just been re-elected so football is put on to his plate, actually by the Headmaster of the prep school that his kids are going to. He writes Roosevelt a letter and says, “The game is danger, if somebody doesn’t do something, it’s going to go away, and that someone has got to be you,” he says to the President.

So, Roosevelt does get involved basically, he decides in October of 1905, something has to be done. His own son has actually suffered a couple injuries on the field as well, so he calls a meeting. And I always think this, football is America’s sport, so as George Will said, “It’s got violence and meetings,” right? So Roosevelt calls a meeting at the White House. He invites basically the coach and the administrator from Harvard, Yale and Princeton to come to the White House for a football conference.

And so, just imagine this scene. You’ve got football coaches in the White House sitting across the table from the president, the Secretary of State attends this meeting as well, and for two hours, these men debate back and forth over what should be done about football. And Roosevelt says at the forefront, he’s pro-football. He wants football to survive. But he always wants there to be some changes made. And this meeting goes on for a couple of hour. Unfortunately there’s no transcript. There’s a lot of newspaper reporting from the day after, saying here’s what we heard happens but we don’t know exactly what happens.

But after this two hour meeting is over, Roosevelt has to go back to work and he basically tells these leaders of football, I need a statement right way that’s going to point towards change. What’s interesting about this story in some ways is Walter Camp, who’s the leader of football at Yale, a really influential football founding father, he had a bad attitude the whole meeting, he doesn’t think Roosevelt should be involved and Camp leads this group as they’re going home on the train to draft a really toothless statement saying that, “They met with the president, they all agree football should survive, and the path forward is simply to make sure that the rules that are in place are followed.”

And as I say in the book, I suppose it’s possible that this group could have done less in response to the President, but I can’t see how. They basically do the bare, bare minimum. But with that said, that’s why I think it’s tough to say Roosevelt saved football, with that said, Roosevelt had done some important things. He invited these coaches to the White House. He gave the game another stamp of his approval. People already knew he was a fan. And what happens after Roosevelt’s meeting with these leaders is a series of additional meetings are held, which will lead to the establishment of the NCAA in 1906 and so football is saved for the time being. And Roosevelt’s a part of that process.

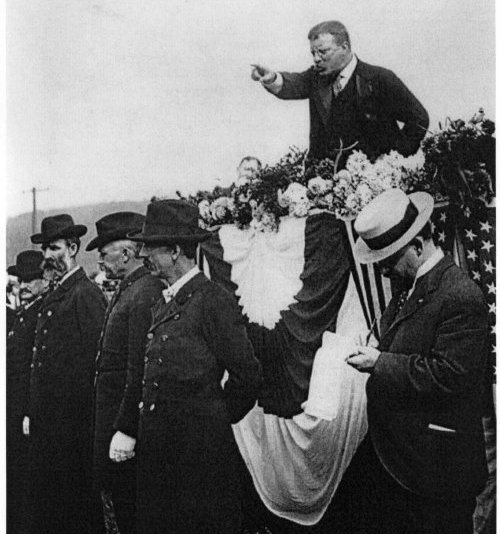

Brett McKay: All right. So as President, Roosevelt helps support athletics by lending his support to football, but he really helps popularize this idea of the strenuous life in general back when he was Governor of New York with the speech he gave in 1899 in which he coined the phrase, “the strenuous life” And this stuck and inspired his fellow citizens and TR didn’t just talk about the strenuous life. He really lived it himself. In the White House, he continued to box until he injured an eye, then he took up Judo, and he famously built or his wife famously built a tennis court outside of his office where he hosted the Tennis Cabinet. So, who was a part of the Tennis Cabinet, and besides playing tennis do they do anything eel strenuous together?

Ryan Swanson: The Tennis Cabinet is a group of about 35 mostly DC insiders, to put it in a broad term. These are people who held positions in the government or the civil service and they were around Roosevelt. So, this is a group that gathers together that plays tennis, as you’d assume from the name, and they become really important, unofficial advisors to Roosevelt. So when you think about the tennis court, as you said, just to give some context to it, Roosevelt comes into the White House in 1901 and the place is in terrible repair, so Roosevelt oversees a massive renovation of the White House. About $600,000 is granted from Congress to do this. A lot of important improvements are made but right outside of the executive office, I’m talking three or four feet from where Roosevelt sits and works is a tennis court.

And there’s some debate over who put it there, as you hinted at. There’s pretty good case to be made, that Edith, Roosevelt’s wife who oversaw the ground’s renovation had put it there in order to encourage her husband, who always battles with his weight, to play tennis. So that’s why the court is there. So this group develops of unofficial advisors who are always willing to come and play with Roosevelt. Three of them become the most important to Roosevelt. James Garfield, the son of the former President who works in the government, he comes and plays. Gifford Pinchot who is the Director of Forestry, a really important conservation voice, and then Jules Jusserand, who’s the Ambassador from France.

And these are individuals who will come, for example, on a January day, when it’s raw and cold in Washington DC and Roosevelt wants some exercise. So they’ll come and play tennis. Or they’ll toss around the medicine ball. Or as is part of the book as well, they’ll head off through a strenuous walk through Rock Creek Park. And they will ford rivers and climb up granite cliffs and all the while talk about what’s going on.

So I think in some ways, these are both informal, yet important meetings. Roosevelt very much works through ideas as he is exercising. His whole life basically, he’s been trying to combine mind and body. And so the Tennis Cabinet is really a way that he does that and the tennis court itself becomes a cultural touchstone, the idea, “Look at the President, he’s got a tennis court right outside of his office. It’s super hot in August but he’s still out there sweating through a three set match, why aren’t you getting out of your office or why aren’t you getting out of the factory and doing the same thing.” So it goes back again to this broader understanding of athletics.

Brett McKay: So did Teddy Roosevelt’s vigorous lifestyle, did that have an influence on the American public? Did people look at hm and be like, “I’m going to exercise just like Mr. President is.”

Ryan Swanson: I think so. I think so in some ways, tracking down the answer to a question like that is difficult, but what we do know is the press over and over tells stories of the President exercising. Which means that there’s obviously an appetite for these kinds of stories. So they will talk about Roosevelt playing tennis. They’ll capture the idea of him going for a long walk, a vigorous walk. For example on the night of his 49th birthday, he goes for a three hour walk in the rain and the press tries to give him space, but they also report on the fact that look at this guy, he’s turning 49 years old and he just went for a 10 mile walk in the cold rain of October. So yeah absolutely, I think the President’s example makes exercise and athletics something more personal for many Americans.

Brett McKay: And he’s probably the first president that actually exercised in a systematic way. I can’t imagine Garfield doing exercises Roosevelt McKinley. It was probably Roosevelt was the guy who started this whole thing.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah, I think so. I think there were presidents before him certainly who did physical labor even. They’d get out and work on the grounds or when they went away from the White House, they would chop wood, they’d do those kinds of things. But yeah, Roosevelt playing sports or going for these trail runs, this is something new. And as I point out, in the first year of his presidency, more than 10,000 times in the press, Roosevelt is described using the strenuous life moniker. The strenuous president, he’s a strenuous walker, strenuous eater, so yeah, the idea that Roosevelt is something new and exciting is absolutely part of the appeal at this time.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about another American sport that has a connection with Roosevelt and that’s baseball, so Roosevelt loved football, was a fan, not so much with baseball. Tell us a story there.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah that’s putting it nicely, not so much with baseball. So Roosevelt never likes baseball. In the book I try to summarize what’s going on. I say that Roosevelt has a cold war with baseball. So, baseball at this time is very popular. It’s by far the most popular professional sport in the United States and Roosevelt comes into the White House as I said, 1901 and during the time that Roosevelt is in the White House, from 1901 until 1909, baseball attendance at professional games doubles. So, the game is really popular.

Also during that time in 1903, the first World Series happens. So baseball is booming. Despite that though, Roosevelt will not give it the time of day. I found it funny, but over the period from 1904, 1905, 1906, into 1907, professional baseball leaders make increasingly desperate attempts to get Roosevelt’s attention. Because what they’re noticing at this point is Roosevelt is strongly associated with strenuous activity and sports. They also know that the President is really popular. He wins re-election in 1904 by a landslide and they also notice he talk about boxing, wrestling, football, these long walks, but he never mentions baseball.

So what baseball leaders do is they come to the White House to visit the President. And Roosevelt is always interested in interesting people. He lets all kinds of guest visit him. And so for example, in 1905, the leader of the American lead, Ban Johnson comes to the White House, and hand-delivers to Roosevelt a golden ticket. And this golden ticket gives Roosevelt entry to any game in the American league, especially the hometown, Washington Senators. He can come for free at any time. He can bring as many people as he wants, gold ticket. Roosevelt thanks Johnson for the ticket, and then promptly never uses it.

And then the same thing happens the next year. The leader of what will becomes baseball’s minor leagues, comes to the White House, gives Roosevelt a golden ticket, says, “You can come to any minor league game in any state for the rest of your life, we’d love to have you.” Roosevelt accepts the golden ticket and never uses it. And after this happens, increasingly baseball friendly writers in the press ask what’s the deal with Roosevelt, why won’t he give the game attention?

And it becomes a rather awkward standoff. But Roosevelt digs in his heels. He will not attend a baseball game. He does not care about the World Series, which is starting and it’s really unusual, given how much he talks about and writes about sports otherwise. And I do speculate best I can about why Roosevelt won’t give baseball the time of day and there are a couple of reasons, which we don’t have nay silver bullet explaining exactly what’s going on.

But Roosevelt doesn’t like that it’s professional. He sees that’s a problem, but I think more practically as that, Roosevelt doesn’t see baseball as fitting his paradigm of what a sport should be. It’s not violent, first of all. It’s not like football. It doesn’t teach men those skills, and then it’s also not physically fatiguing. It’s not the same as going for a 10 mile hike or playing five sets of tennis. You don’t sweat a lot as a baseball player, and it doesn’t make you better in those ways. So Roosevelt just ignores the game throughout his whole life, and his daughter Alice will say at one point, “That Father and us,” she says, “all hated baseball, because it was too mollycoddle.” And you probably know that word or heard that word, it’s basically, it’s not manly enough thing.

Brett McKay: It’s a wussy game, according to Roosevelt.

Ryan Swanson: It’s a wussy game.

Brett McKay: But there’s been some comeuppance in baseball since then, you point out. So there’s the Nationals, they have that race with the presidents, through the bobblehead president looking guy, Roosevelt has never won the race ever.

Ryan Swanson: Well actually, so for a long time the Nationals…. So, yes I point out that the Washington Nationals, for those people who aren’t familiar with this and why would you be unless you lived in DC, in the fourth inning, they have a Presidents bobblehead race. These huge-headed mascots race around the National’s field to keep the fans entertained during the mid-inning change. The same as I think they have sausages run around in Milwaukee and whatever else in other places. And for 525 straight games, Roosevelt was not allowed to win the race and it became a real thing in DC. They did a mock documentary and they got a call for Roosevelt to win, and I argued that whether the Nationals knew it or not this was really great historical comeuppance.

But to bring it around, the Nationals did let him win, and in fact, this season, he has won the season championship among mascot races. For those of your listeners paying attention to baseball right now, you’ll note the Nationals are in the World Series, so perhaps Roosevelt is being totally forgiven by the baseball gods and the Nationals will win the world series. We’ll know, I suppose by the time this airs, but the mascot race and the LetTeddyWin.com community is an interesting way to think about Roosevelt’s legacy in sports that still endures.

Brett McKay: So all throughout his presidency, Roosevelt stayed active. When he left office, he was very active, you didn’t talk about these parts in detail about his life, but he went on a safari in Africa. Then he went and did the River of Doubt thing where he almost died and explored an uncharted part of the Amazon River. But then the part you highlight, his continuation of the strenuous life after his office, is the end of his life, where he goes to this farm, to get in shape. Tell us about that and why did you focus on that part of Roosevelt’s strenuous life.

Ryan Swanson: To be honest, it’s my favorite part of the book, my favorite part of the story, at least in terms of how it resonated for me. So as you said, Roosevelt leaves the White House, 1909, he’s only 50 years old. He has plenty of adventures after, the River of Doubt, he runs for election again in 1912. He does a lot of things.

Brett McKay: He gets shot.

Ryan Swanson: He gets shot, yeah and then gives his speech. So he’s hardly living some ordinary sedentary life, but I would argue that by the time 1917 rolls around, Roosevelt looks around and worries as probably many of us do, that the world is passing us by. He’s getting towards his late 50s. He tries to get Woodrow Wilson to let him be a part of World War I. It’s a delusional, I don’t know maybe noble but certainly delusional idea that I’m going to get a modernized Rough Riders and we’re going to go over there and teach the Germans a thing or two.

Wilson doesn’t go for it of course, you’re not going to send an old president over to this World War that’s going on. So with all that going on, in 1917 in October, Roosevelt decides to go off to training camp. And really at the urging of his wife too. As I mentioned, Roosevelt battles with his weight his whole life. He’s really active, he’s really vigorous, but he eats like a teenager basically his whole life. As much as he wants, whatever he wants, whenever he wants. So he’s always trying to burn off the calories, but the math doesn’t quite work out in terms of how that plays out.

So, 1917 he goes off to Jack Coopers Health Farm it’s called. It’s in Connecticut. And it’s a place dedicated towards, what we were talking about in the beginning, the idea of healing yourself from the ills of modern society. And so, individuals would show up, and get this former boxing champion Jack Cooper to train them for a couple of weeks. So, in my mind this is the best part of Roosevelt’s athletic journey because it’s so relatable. It’s so, I don’t know intriguing, maybe even inspiring in certain ways.

So he gets there. He’s 58 years old. He’s about 30 pounds overweight. Former President, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, all these things, he turns himself over to Jack Cooper and basically says, “Give me your worst, I’m ready. I want to get back in shape.” So Jack Cooper for two weeks, works with Roosevelt and just puts him through the grinder. He gets him up at 5:45 to run three or four miles, then he puts him in the gym for some sparring and then he gives the medicine ball workout and then in between all these things, he has him try some of the inventions, the exercise inventions he’s got.

So he’ll put him on a bicycle, which is cloaked in leather, which has a heater inside of it to try to get him to sweat some of his weight off. Then he’ll have him massaged, then he’ll take a cold shower, and then he’ll repeat the whole process over. So for two weeks, Roosevelt goes through this, and what I think it shows is that at 58, with all of these things behind him, and 30 pounds overweight, Roosevelt is still trying to live the strenuous life. He’s still getting after it, which I think is pretty interesting.

And on the last day of his time at Jack Cooper’s farm, he lets the press in. Roosevelt still loves the attention. He’s not above talking to reporters to his own glory. He lets the press in, and someone who comes is John Mitchell, who is the Mayor of New York City. And so all these people are around, and Roosevelt is talking about the two weeks that he has and he says I’ve lost 14 pounds and everybody is impressed. And this is as World War II is ramping up, and the nation still cares so much about Roosevelt, that this is front page news.

And what’s funny I think to wrap things up is Roosevelt wants to show them the half mile loop that he’s been running every day to try and get back in shape. So he says “Come with me, I’ll show you what I’ve been doing.” So he heads off around this half mile loop around a pond, and in typical Roosevelt fashion, he turns it into a race. Starts slowly jogging and everybody gets spread out behind him. John Mitchell, who thought he was there for this easy cameo, to get some votes, ends up dropping out and half a mile later, Roosevelt comes across what would be the finish line if it was actually a real race and he’s victorious. And the press gathers around him and talks about how vigorous he is.

And Roosevelt for one last time, gets to get expound upon how this strenuous life is a constant struggle, always get after it, always try to get it. So yeah, this is why I end with Roosevelt here, because this comes shortly before his death. He passes away at 60, but think Roosevelt was always going after this strenuous life. So this story, which hasn’t been much covered, I think was good way to round things out as his life is nearing its end.

Brett McKay: Well, your book is called Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of the American Athlete. After spending all this time with Roosevelt and his interaction with this cultural movement in America, what lasting legacy does he have? Would sports be what it is today without Roosevelt or did Roosevelt super charge things?

Ryan Swanson: I would say both of those characterize it. Sports would not be what is today without Roosevelt, at least slightly. He plays a role, he’s not the only part of the story but I think I like your idea and I used the reference to a super collider this time. He super charges sports.

So what I think Roosevelt does is that at a pivotal moment in American history, he helps Americans understand how sports can play a role in making them better individually and collectively. And Roosevelt supports things like sports in schools. He supports college football. He buys into the paradigm of sports being put in place, which still basically exist today, by the way. So I think Roosevelt’s fingerprints are still all over our society as a whole, and especially athletically. So I think the connection is an important and valid one for us to understand.

Brett McKay: So let’s do some armchair psychology speculation. All right. You spent a lot of time with Teddy Roosevelt. I’m curious, we live in, I would say a second strenuous age. We have all this stuff Cross-Fit, power lifting, Jujitsu, MMA, rucking, obstacle races, if Teddy Roosevelt was alive today, which strenuous 21st century activities do you think he’d take part in?

Ryan Swanson: Boy, that’s a good question. So Roosevelt, in some ways he’s trying to balance, right? He’s always looking for something that appeals to his intellectual side, his curious side, but is also challenging. I think Roosevelt would be in favor for example, Cross-Fit. I think he would love the idea of broad participation. Everybody can get in and do it, but at a different level and we all go for the extreme. Whether you start at position zero or position 70, the point is to get as far say from your beginning point as possible. So, I think he’d like Cross-Fit.

Another thing, modern manifestation of this strenuous life that he’d like, I think he’d like some of the endurance, 50K endurance across really difficult terrain or even the mud runs that exist now. Get out and get muddy and go over the obstacles and compete in that way. I think he would like those kinds of things as well. Roosevelt was never about being the champion. He famously said of himself, “I never was champion, but people can learn from my examples of how to be an athlete anyway.” So, he would favor broad participation, extreme sports events.

And one key characteristic of Roosevelt in sports is he was never afraid to look stupid. He would try anything. He didn’t care if he got dirty. He didn’t care if he wasn’t very good. It was about effort and so those would be the kinds of things that he would like. I think more as opposed to MMA, which maybe he would participate on, on some level, but I think it would be more towards Cross-Fit or one of these extreme endurance runs or something like that. But it’s fun to speculate, I think for sure.

Brett McKay: Right. Well speaking of those endurance events, Roosevelt I think plays a direct role in that. So I think when he was President, he came with this idea that all officers in all branches of the military should be able to march 50 miles in a total of 20 hours. And it got forgotten and then JFK, when he was President, resurrected it and I think Bobby Kennedy decided he’s going to try and do this 50 mile walk in his loafers and it was winter time and he did it. Then after that you saw this movement of people in the 60s, 70s and 80s, they would do these 50 mile endurance walks.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah, yeah. I think so.

Brett McKay: And it’s all because of Teddy Roosevelt.

Ryan Swanson: Yeah, I think he absolutely sets that example of it’s not always the high-profile, it’s the struggle. And so an endurance race or an endurance walk is an example of this struggle. It may not be this acute pain that you have at one moment, there may not be this glorious, but can you stay at it for five or six or seven hours? Can you get through this river or this mud? So yeah, I think there’s a real connection to Roosevelt. Because Roosevelt as president gives it value, it allowed it to become more acceptable in society and more sought after, so I think that’s absolutely important.

Brett McKay: Well, Ryan, where can people go to learn more abut the book and your work?

Ryan Swanson: The book is being sold at all places books are being sold and they can find it there. In terms of where you can see some of the other writing that I’ve done, both popular and otherwise, my website is ryanswanson21.com. So ryanswanson21.com. And so I’ve got articles and things posted there that I’d love for people to check out.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well Ryan Swanson, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Ryan Swanson: My pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Ryan Swanson. He is the author of the book The Strenuous life, Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of the American Athlete. It’s available on Amazon.com. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/strenuospresident and find links to resources, where we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you can find our podcast archives plus thousand of articles we’ve written over the year about physical fitness, how to be a better husband, better father and speaking of the strenuous life, check out our online membership program called The Strenuous Life, inspired by Teddy Roosevelt’s idea of the strenuous life. It’s an online membership platform where we help you put into action all the things we’ve been writing about and talking about on the art of manliness website for the past 10 years.

We’ve got badges, based around 50 different skills. There’s hard skills like self-defense, wilderness survival. We also have a Teddy Roosevelt Rough Rider badge where you do some things inspired by Teddy Roosevelt like swimming in rivers, taking long hikes, things like that. We also hold you accountable for your physical fitness, doing a good deed, thinking outside of yourself and we provide weekly challenges that are you going to put you outside of your comfort zone. So check it out. Strenuoslife.co. Our next enrollment is in January 2020, so get your email on our waiting sit to be one of the first to know when enrollment opens up in January 202. S check it out, strenuouslife.co. One more time, strenuouslife.co. I hope to see you signed up as part of the strenuous life in January.

And if you’d like to enjoy ad free episodes, video and podcasts you can do so on Stitcher premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com/signup. Use code manliness to get a fee month trial once you’re signed up. You can download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and start enjoying ad free episodes of the AOM podcasts. If you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already thank you. Please consider sharing this show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support and until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.