For thousands of years, the Spartans have captured the imaginations of Westerners. In ancient Greece, the city-state was admired for its military prowess, civic unity, and dedication to leisurely athletic pursuits. Today, we make movies about Spartans and name sports teams after them. When we moderns think of Spartans, we typically think of them simply as fierce warriors.

But while the Spartans were indeed warriors par excellence, their culture was much more complex. Today on the show, I unpack some of these complexities with historian Paul Rahe. Paul is working on a series of books with Yale University Press which explore both the military and political strategy of the Spartans. We begin our conversation discussing why it’s hard for us moderns to truly understand Sparta. We then dig into the history and culture of Spartans, including where they came from, their economic set-up and relationship with the helot population, and the strenuous upbringing of boys that made them fit for battle. We then talk about the mixed government of the Spartans. We end our conversation discussing how the city-state faded into obscurity, and why the Spartans yet live on in modern culture.

Show Highlights

- How much do we really know about ancient Sparta?

- Why it’s so hard to understand Sparta using our modern cultural framework

- Misconceptions we have of ancient cultures

- The role of secrecy (and brevity) to Spartan culture

- Where did the Spartans originally come from?

- The history of the Helots (the subjugated peoples of Sparta), and why it wasn’t slavery in the way we understand it

- The agoge — the Spartan training program for children

- Where did Spartan boys go after the agoge was completed?

- The role and importance of art — poetry, music, pottery — in Sparta

- Why Sparta was looked up to by their contemporaries

- Laconic wit and brevity

- How Sparta was organized differently than other city-states

- What Spartans were like in battle

- How long did the Spartan regime last?

- Why does popular culture seem to praise and look up to Sparta more than other city-states?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Spartan Way

- Courage vs. Boldness: How to Live With Spartan Bravery

- Manvotional: Spartacus to the Gladiators

- The Power of Secrets in a Transparent World

- What Ancient Greeks and Romans Thought About Manliness

- Homer’s Odyssey

- Helots

- Dorians (ethnic group)

- Tyrtaeus (Spartan poet)

- Hoplites

- The Gates of Fire by Steven Pressfield

- The Tides of War by Steven Pressfield

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Podcast Sponsors

Candid Co. Clear, custom made aligners to straighten your teeth at home. 65% cheaper than braces, saving your thousands of dollars. Get 25% off your modeling kit by visiting candidco.com/manliness.

Thursday Boots. Money. Power. A great pair of boots. You can have it all! Visit ThursdayBoots.com to get your pair today.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the art of manliness podcast. For thousands of years, the Spartans have captured the imaginations of Westerners. In ancient Greece the city state was admired for its military prowess, civic unity and dedication to leisurely athletic pursuits. Today we make movies about Spartans and name sports teams after them. When we moderns, think of Spartans, we typically think of them simply as fierce warriors. But while the Spartans were indeed fierce warriors, their culture is much more complex today. Today on the show we unpack some of these complexities was historian Paul Rahe. Paul is working on a series of books with Yale University press, which explored both the military and political strategy of the Spartans.

We begin our conversation discussing why it’s hard for us moderns to truly understand Sparta, we then dig into the history and culture of Spartans, including where they came from, their economic setup and relationship with the helot population and the strenuous upbringing of boys that made them fit for battle. We then talk about the next government of the Spartans and we end our conversation discussing how the city state faded into obscurity and why the Spartans, yet live on in modern culture. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/sparta and find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic. Paul joins me now via clearcast.io.

Paul Rahe, welcome to the show.

Paul Rahe: Pleasure to be here.

Brett McKay: So you are a professor of history, political history, and you’ve written some books. You’re working on a series of books about Sparta. So the Spartans, I think are intriguing because they enjoy a very prominent place in our collective and popular culture. There’s movies made about Spartans, books written about Spartans, teams remained are named after Spartans, so I think we feel like we know them well. But in your book, on the first one in this series, you quote Winston Churchill, his phrase describing Russia and used it for the Spartans saying there a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. So do we actually know much less about the Spartans than is commonly thought?

Paul Rahe: Well, it depends on what you mean by the word, no. If you mean do we have less information about them than about other communities, the answer is we have more information about them than about most communities. The obstacle to our understanding is the way we see the world. We live in a liberal regime, it’s a product of a certain kind of political science, and we’re used to thinking in terms of say the primacy of economics, are you better off now than you were eight years ago, being the sort of thing a presidential candidate could say in running against someone who is in office, but also we think primarily in institutional terms, separation of powers, federalism and so forth. The ancient Greeks thought in different terms and let me give you an example of how that might be.

In the 19th century, we forced Japan to open up and the Japanese horrified by our military intervention in Tokyo harbor, sent the crown prince to the great capitals of Europe and they invited the European powers to send embassies to Japan. They were looking for support against us and in England, a conversation, I am told, took place between an English civil servant and one of the attendance of the Japanese crown prince and the English civil servant asked, “What were your instructions?” And the Japanese, the attendant to the crown prince said, “I don’t quite know what you mean.” And he said, “Well, we send an embassy to Japan in our instructions were to find out what do they produce that we might buy, what don’t they produce? We might sell to them, what are their defenses like do they have navigable rivers and so forth?”

The Japanese, the attendant to the crown prince responded, “Ah, now I see,” he said, “We were asked to find out what do the English bowed down to.” When we think of a political regime or a form of government, that’s not the first question we ask, but in a way that’s the first question you have to ask in order to understand the Spartans. When I talk about the Spartan regime, I’m talking about a whole way of life, a set of practices that began with birth and end with death, that are set by the spartan laws and by Spartan Customs that essentially have the force of law and not just about the distribution of powers between different magistrates.

When you look at it that way, we have a great deal of information about spartan because Aristotle was interested in this, Plato was interested in this and Plutarch was interested in this, Xenophon was interested in this, and Plutarch had access to certain writings of Aristotle, the constitution of the Lacedaemonians, that we don’t have any drew rather heavily on it. So we get a kind of comprehensive picture of Sparta if you put together what we’re told by Herodotus and Thucydides and Plato and Xenophon, Aristotle and Plutarch, and you can begin to see how the whole way of life works. So that’s one obstacle.

Another obstacle is we tend to think of a city as urban, but the Greek palace actually was rural in character. There was a town, but the vast majority of the citizens were farmers from the countryside and that distinguishes by the way, the ancient Greek city and ancient Rome from places like Venice and Florence, where it’s the titadine who live in the tetons in the city who are citizens and the contadine who live in the rural district called the Cantado are not citizens they’re subjects. So the Greek city is agricultural in character and that shapes it profoundly.

Brett McKay: I guess the problem is it’s hard to know because in a way it’s very foreign to us. We tend to think of Sparta, the Greek city states using what we know about politics or what a city is and when we do that, there’s a mismatch and so you miss the mark a bit.

Paul Rahe: Right, we read certain elements in the makeup of say Athens and we put great emphasis on them because they’re familiar to us, or there’s something like what we know and then we miss what is alien. That’s a common phenomenon and it infects international relations a great deal. We have a tendency to read our own predilections into foreign countries and the consequence is we very often misinterpret what they’re up to because it’s so alien to us. We don’t pay much attention to what we would call cultural differences, but what the ancient Greeks called regime differences.

Brett McKay: Another thing that makes it mysterious than too, we have descriptions from ancient historians and ancient philosophers or injury political scientists like Aristotle, of the Spartan way of life. So because Sparta was really a way of life, you know, it’s not like today where we can look at our government as you were saying earlier, and see these institutions that define us, for Sparta government or the regime it was internal. It was actually something like it was baked into the person and so to really understand that you have to see it in action or see descriptions of it in action. You can’t just look at a constitution and get … You can get some glimpse of it, but you’re not going to get the whole picture.

Paul Rahe: That’s right. You’ve got to look at the way of life. It’s as if to understand America, you have to understand Monday Night Football. Right?

Brett McKay: That makes sense. But also were the Spartans secretive in any way, like were they very reluctant to allow outsiders into their community?

Paul Rahe: They were secretive in two different ways. They were laconic, our word comes from a name for them, Lacones. They were laconic, meaning they prided themselves on the brevity of what they said. It’s like the Vermont farmer who answers every question, up, up. That was one aspect of set of habits. Second aspect of it is they didn’t allow foreigners to come to Sparta except with permission, and they didn’t often give permission, and they didn’t allow their own citizens to travel freely. Once again, you had to have permission and they didn’t give permission for young people to leave, lack a dime on, so they were a mystery even in their own time and sometimes it was hard to get information.

Thucydides in one passage talks about the crypton taste politaires, the secretiveness of the regime. For example, he is trying to figure out how many soldiers they put in the field and it’s hard to get a fix on it for him and he’s actually spent time at Sparta so they’re terse. They’re brief and what they say, they’re secretive and then they have institutions that make it hard to for you to get access to them.

Brett McKay: Well let’s talk … we will get into more of these institutions here in a bit, but let’s talk about the origins of the Spartans. They settled in an area, but they’re not originally from there. Where did the Spartans come from and why do they settle in this one part of Greece?

Paul Rahe: We can only speculate on the basis of legend. They seem to come from northern Greece, from the other side of the Corinthian Gulf. There is a legend that they crossed the Corinthian Gulf on rafts, which it’s quite possible to do, there’s one place where there’s only a mile across and they see themselves as invaders. Now, ordinarily that would be something you wouldn’t say about yourself that are alien to the place because it undercuts your claim to be the legitimate landholders there. The Athenians for example, insists that they’re born from the Arith, that is to say that they sprung up from the territory, their blood and the soil are one and the same. The Spartans make a different claim about themselves and it’s probably true because it’s to their disadvantage.

They counter the attack on them that would be made that they were interlopers, didn’t belong there, claiming that they are the followers of the true owners of the land who were the descendants of the hero, Heracles who was a prince from the northern Peloponnesus who is said to have earned by his laborers a claim to the Peloponnesus as a whole and his heirs down the generations had made multiple attempts to make good on that claim and they only succeed when they are leading these Lacedaemonians into the Peloponnesus and then they move into the richest part of the Peloponnesus in terms of good land, which would be Laconia.

They are Dorian’s, they say, and the Macedonians are Dorian’s too, and came at the same time and they are guys are Dorian’s too and came in the same invasion so these are three peoples who have a common legend. I’m inclined to think there’s probably something to the legend, these things tend not to be made up out of whole cloth. They tend to be … there tends to be a kernel of truth and around that kernel of truth that gets charted up and in a variety of ways. We know that there is a new people in, and we know this from archeology, in Lacedaemon somewhere around the 10th century and at some time in the eighth century BC, we can begin to see evidence of farming settlements.

These people may have invaded and they may have brought flocks with them, that may have been the way they operated. There’s much in their mythology that would suggest a connection with trans humans, that is to say with conducting flocks from the highlands where they would be in the summer down to the lowlands in the winter. We can’t be sure about any of this.

Brett McKay: How soon did we start seeing in political organization that started … we could say that it was okay, this is starting to look like something like Sparta?

Paul Rahe: The evidence would suggest by about 750. You’re beginning to see something more than bands led by chieftains and you’re beginning to see a settling down and a turn towards agriculture and there appear to be five villages and there’s four in one place and then there’s a fifth village, a bit to the south that seems to have been incorporated into Lacedaemon. There’s clearly a population in Laconia, which is where they first go, before they get there and we have legends about that. You can see it in homer’s Odyssey and the account of Telemachus’ voyage from, initially from Ithaca, to Piros in Messena and then onto Lacedaemon where he meets Minereys and Helen and recently, and I mean in the last five, six years they’ve discovered a Mycenaean palace in southern Laconia. Not where Sparta is but south of where sport is and that may well be the palace that Telemachus is supposed to have visited.

There is a kind of overrunning by the Lacedaemonians of Laconia and whatever population is there when they arrive, much of it gets turned into helots, subjects.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about the helots.

Paul Rahe: There are two kinds of helots. There Are helots in Laconia, sometimes they’re called by the Spartans the old helots, the old helots. They are probably a kin in origin, you’ve got to think about the population that existed under Minaretas and Helon. Then there are the helots of Messina. Sometime towards the end of the 8th century and are our dates become a little more solid when you get towards the end of the eighth century, say 720, 715, the Spartans cross Mt. Taygetus, which is a range of mountains that run north and south between Laconia in the east and Messina in the West. They cross those mountains and they conquer the river valley in Messina, the Valley of the Permessos, which is even richer than the river valley in Laconia where they live, and they subject the people of Macedonia who are Dorian’s like the Spartans, and they then draw income mainly in the form of agricultural products from Messina.

It’s at this point that the Spartans begin, we have some reason to think, to develop a way of life based on leisure and on leisure devoted to gymnastics and to sports and of course the war.

Brett McKay: So the helots, people often think of them as slaves. Were they slaves, like similar to other Greek city states practice slavery, was it different?

Paul Rahe: No, they’re not slaves in the traditional sense. They’re not chattel, they can’t be sold. They’re not owned by a particular Spartan individual. They are subject to Sparta as a community and in a sense are owned by Sparta as a community, but they don’t operate for the most part in the households of individual Spartans. They operate on farms from which they are required to provide a kind of competence for individual Spartans. So there’s an allotment of land assigned to each individual Spartan, more or less at birth, probably takes possession of that land when he completes the agoge and becomes an adult, and then he receives from that land a portion of the crop. So these helots or like sharecroppers, but they’re also like serfs because they’re bound to the land and there’s something like slaves because they really have very limited rights.

Once a year the Spartan efforts declare war on the helots and it’s an opportunity to kill a helot if you want to kill a hell lot so it’s an unenviable status to say the least, but it’s not like slaves. So for example, if you’ve got to Athens, they have loads and loads of slaves. Most of the slaves are barbarians and they are owned by individual Athenians and they don’t have families, they’re not settled on land that they have some sort of claim to. The helot has a claim to the share, to a share of the crop that he produces from the land that he works so it’s a more complex status. In some ways better off than slaves are because these helots of families and they have some sort of claim to a share of the crop. In other ways which have to do with the brutality of the Spartans, maybe they’re worse off than slaves.

Brett McKay: The noticeable thing about the helots is that they outnumbered the Spartans considerably, I think it was that one number was estimated seven to one.

Paul Rahe: The information we’re provided by Herodotus suggest a ratio of seven to one. They’re modern scholars who think that’s impossible on the basis of sort of social science analysis and land and how many people it will support and so forth. I’m skeptical of such analyses.

Brett McKay: Whatever the number was, how did the Spartans keep these guys in control? There’s the annual killing, how else did the helots outnumbering them influence how they organize themselves or organized their culture?

Paul Rahe: Probably, and we don’t have evidence for this, but it’s hard to believe that the Spartans didn’t have garrisons in Messina and it’s hard to believe that they didn’t have magistrates that oversaw the helots in particular areas. But the main thing that they used to keep the helots down was terror and it worked in two ways. One, this annual declaration of war and second, they had a way of training 18 year olds. You complete the agoge, which is the upbringing, the kind of formation that runs from about seven, age seven to about 18, and looks like a rather more serious version of the cub scouts and the boy scouts and the explorers.

They then spend a year in which they are given a dagger and they hide out and they have to steal their food. My guess is that a lot of this takes place in Messina and the food is stolen from helots and they do it by night and one of the reasons that they may have this institution of the criptaya is there are mountainous areas in Messenia in particular, and it’s extremely difficult to police mountainous areas. If you look at the Persian empire, for example, there are certain mountainous areas that sometimes the Persian king has to travel through and he doesn’t really control those mountainous areas, there are wild tribes that control them and he has to pay a kind of penalty for passing through.

The reason is it’s not worth the effort and the expense of putting soldiers into those mountains and keeping them there to police those mountains and there’s a long history in the Balkans and elsewhere in the world where there are mountainous areas of bandits and abandoned gangs that maintain control in these wilder areas. One way to counteract that possibility within Messenia is you send out young Spartans with daggers and their task is not to bring back scalps in the literal sense, but their task is to kill these helots, runaways.

Brett McKay: You mentioned the agoge which start at age seven, walk us through it. You said it’s like an extreme form of cub scouts, boy scouts, so what was it like? You’re seven years old, what happens when you turn seven if you’re a boy?

Paul Rahe: You leave your mother and you leave your father. Now your connection with your father is not that strong because he doesn’t really live at home, he visits. He lives in the Sesedia with his fellows in a kind of squad and takes meals there and spends the night there most of the time, may slip off to visit his wife from time to time. But you take the boy away from his mother and you take them into a kind of camping arrangement with other boys his age and you teach him the traditions of Sparta, but you put him through exercises all the time and you teach him poetry. There’s a kind of … they’re choirs of Spartan boys, music is central to spartan life, and as you move from seven to 12, they’re kind of boundaries in this. Then onto 17 and 18, you rise through age … you’re a member of an age class, and as you get older, they do different things with you in the way of the games that you play, in the ways of the ordeals that you go through.

So it, it gets more and more intense as time goes on and more and more physically demanding. You’re being prepared for full citizenship and full citizenship involves military service, but you’re also being prepared for being cunning and being able to operate on your own. One of the striking features, about Sparta in say the 5th century is you, the Spartans could send one Spartan to Syracuse to help the Syracuseans against the Athenians and that can be decisive. A single spartan providing leadership and guidance can so heartened the Syracuse that they outwit the Athenians and defeat them. Similarly, you can send brassiness with a group of emancipated helots and a mercenary army, no other Spartians, up into northern Greece towards Amphipolis and Thrace and he can wreak havoc because the kind of education that he has received makes him self reliant to a degree that is astonishing for the other Greeks. So single spartan can tip the balance.

Brett McKay: You mentioned a few things there that I’d like to unpack. You mentioned part of the agoge training was poetry singing songs, which is interesting because I think a lot of times people think Spartans, they think, oh, they had no culture, they didn’t have an appreciation for art, but right there they have an appreciation for art.

Paul Rahe: Yes, yes. And actually, at least in the early days, the art that is produced within Laconia and I’m thinking of pottery, is quite beautiful there. There seems to be a turning away from that later, but poetry’s absolutely central to their lives and the poetry is focused on war, on the accomplishments of individual Spartans in particular situations. We have snatches of it from a poet called Tortillas who’s a contemporary, he’s sort of two generations after the original conquest of Messenia at a time when Messenia rebelled and the Spartans or reconquering it and his poetry mostly has to do with that reconquest, but it’s very impressive and they memorize it, they memorize large swathes of poetry. Poetry may be more central to spartan life than it is to Athenian life.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that’s interesting. That’s counterintuitive as we think that the Athenians are more cultured and they would put it into some.

Paul Rahe: Yeah. It’s a different kind of culture focused on comedy and tragedy, which you don’t have in Sparta. Sparta, what you’ve got is lyric poetry.

Brett McKay: It’s kind of like ballads of great deeds.

Paul Rahe: Yes, that’s right.

Brett McKay: That’s the other question. I mean, it was like why? The Spartans were able to live this life of leisure thanks to the helots, but why did they decide we’re just going to spend all that leisure time that we have freed up time to become the best warriors possible where, you know, in other city states they like Athens and be like, well, when you have lots of leisure that allows you to do philosophy, why did the Spartans go that way?

Paul Rahe: Well, you got to be a little careful about this claim about Athens and philosophy. The people who did philosophy were considered freaks, they were marginal in character. It’s not an accident that Socrates was executed. The ordinary Athenian … His focus would be more on tragedy and comedy than on philosophy. Philosophy really is marginal. It’s very important to us, it’s the thing about Athens that may be the most important to us, but it’s not so terribly important to 5th century Athenians, at least to the common people. Now the well to do, the hoity toity, the men of great aristocratic families, they dabbled in it. When you think about Sparta, you have to think about it as a kind of combination of a military camp and maybe a baseball camp where you’re working out before the season begins and you have to think about the Spartans as people who love sports.

They love sports, they love horse races, they love hunting, in other words it is not altogether grim. They do not eat meals that you and I would enjoy and in fact they’re notorious for the sort of simplicity of their fair, but when you move into the sphere of sports, it’s a kind of exciting life that they lead and it’s a life of leisure that the upper classes elsewhere in Greece envy the Spartans for, that’s another thing we have trouble with. We admire Athens, but the Greeks generally admired Sparta much more than Athens.

Brett McKay: What do they admire about it? They just admire their pursuit of excellence and-

Paul Rahe: They admired their accomplishments on the battlefield. When he’s in the funeral oration that Thucydides lays out wants to make the case for Athens, the foil is always Sparta and the deciding factor, the thing that decides that Athens is superior to Sparta is Athens wins on the battlefield. That’s the standard and it’s the accepted standard even in Athens so the Spartan success on the battlefield is envied. Their leisure is envied, that’s what everyone would like to have, not to have to work. Their use of that leisure for horse racing, for hunting, that is also admired and the role of music in their lives, that is also admired.

The people in Greece who are most critical of the Spartans are people like Plato and Aristotle who intimate that the Spartans raised their children like beasts. But if you look at the well to do throughout Greece, throughout fossils and Fiplis and so forth, what they admire is this way of life, which of course is based upon a very large subject population. No one in Greece feels any shame about enslaving other human beings, that’s another thing, we have trouble getting our minds around it. It’s just an accepted institution. Aristotle in his politics raises the question whether or not a lot of the people who are in practice enslaved are worthy to be free men with the implication that perhaps a lot of the people who are free men are worthy to be enslaved. So he sets another kind of standard, but you’ve got to keep in mind the philosophers are on the margins here. The mainstream of people are proud of their domination of other people’s.

Brett McKay: I think you were mentioning that the other Greeks, upper class Greeks and other city states admire the Spartans, didn’t some of them actually send their kids to the Spartan agoge?

Paul Rahe: Well, yes. Xenophon did for example, an Athenian. There wasn’t a whole lot of that and it may not have happened in the 5th century. It certainly happens in the 4th century because we begin hearing about it in the 4th century and the Spartans open up a bit in the fourth century because after the Peloponnesian war, which they, when they establish an empire throughout Greece, more or less an imitation of the empire that the Athenians had had and in establishing an empire, they have to open themselves up to the larger world and that that is consistent with bringing people to Sparta and putting them through the Spartan agoge. One consequence of this, by the way, is our best information about Sparta comes in the 4th century when they’re forced to open up in this way in the writings of Xenophon, Plato and Aristotle.

Brett McKay: We mentioned the agoge, that’s something that the kids went through their education. What happened after that? You mentioned they kind of got assigned to a squad basically?

Paul Rahe: Well, in between comes the krypteia, the sort of testing time where as individuals they’re given a dagger and they are sent out into the wilds to fend for themselves. So that’s a rite of passage, and at the end of this rite of passage, they can be elected to a particular sesedia which is a men’s dining club/military squad. It is one of the elements within the Spartan army so if you were to fight in the Spartan army, you will fight alongside or quite near in the battle line, the members of your sesedia and until you’re 45, at least that’s what I think, there are others who think that there’s an earlier date on this, you take your meals in the sesedia with your fellows who have elected you to member, sit in it and one of them doesn’t want you, they can blackball you, it’s like certain fraternities.

Second, you spend the night with your squad. So Sparta is like an encampment, a military encampment. There are houses for the women and the children, the men have something to do with those houses, but they tend to spend their nights with the military squad. So in an emergency, a king can have an instrument called the solpinks blown and they can rise up, they’re already in their military units. They can rise up, form up into a battle line and fight

Brett McKay: What do they do in these clubs? They just talk and joke, what do they do in these dining clubs?

Paul Rahe: Telling stories, telling jokes, it is this that gives rise to their brevity. In other words, there’s a certain style. It’s a little bit like Twitter, you’ve got to get everything into a certain number of words, so quips as something that they’re very proud of and it’s a kind of literary style. You’ll say something to a Spartan and he’ll have a zinging comeback, not unlike a fred astaire Ginger Rogers movie.” I can think of one where a woman says, to Ginger Rogers, “You’re not as dumb as you look.” And she says, I wish I could say the same for you.” That’s the kind of comeback that a Spartan would have.

Brett McKay: You said the Spartans every now and then went and saw their families, when did they go see their families?

Paul Rahe: They may have visited them in the daytime in between the other things that they’re doing there. There are stories about them slipping off at night to visit their wives which is how procreation takes place.

Brett McKay: Interesting. It sounds like the life of a Spartan, it was very public. You didn’t really have much of a private life. You did, everything with other people. There really wasn’t much going on that you had for yourself.

Paul Rahe: No, there’s not much. After 45, maybe there’s a little more if you live that long, and of course not everybody lives that long. The likelihood is that when you get to be 45, you’re in the grave, but not always and then they live at home, but there’s another side to it. This attack on privacy, pulling young people into the public sphere at age of seven when they leave their mothers and the keeping of the men in the public sphere through the sesedia until they’re 45, it may provoke a reaction. One of the interesting things is that we have the sayings of the Spartan women.

You’d think the Spartan women would be inconsequential and yet we know much more about Spartan women than we know about Athenian women. It could be that if you take a boy away from his mother at the age of seven, you intensify the relationship between the boy and the mother by depriving him of the close contact and a lot of the sayings of the Spartan women are sayings of Spartan women to their sons, you know, come back with your shield or on it, meaning come back with your shield, not having thrown it away as a coward does or on it as a dead man, those are the choices. Think of having a mother like that.

It also they could be the relations between a spartan men and their wives are quite intense because they’re kept apart the way they’re kept apart and so you cherish the time together much more. It’s very hard to tell, but when you have a society that is organized in such a way that it emphasizes the public, you may get a kind of natural human reaction that emphasizes the private. I mention this because one of the other things that were told about the Spartans by Plato in particular is their houses are very simple on the outside, but they’re very luxurious on the inside. Another thing we’re told, and it seems almost certainly to be true, is the Spartans are notoriously opened to bribery. In other words, there is this kind of suppressed private concern for wealth and the suppression intensifies rather than eliminating it.

Brett McKay: The Spartans also were famous for their sumptuary laws where … they couldn’t even own money publicly. They used these big metal.

Paul Rahe: But apparently in the houses there’s money buried.

Brett McKay: Right, that’s interesting. When you suppress it, when you say, oh, we do not do this for money, we do everything for glory. If you suppress that desire for wealth then people privately are going to go crazy with wealth.

Paul Rahe: Yeah. Yeah. Look, if you have separate schools for boys and girls, their interest in one another is intensified, not Reduced.

Brett McKay: We haven’t talked about Sparta as government. Tell us about that, how is it unique from other Greek city states?

Paul Rahe: As far as the first constant has the first sort of institutional structure that we know of that involves what you might call a distribution of powers and a kind of checking and balancing. In the beginning that the dominant figures at Sparta are the two kings. There are two kings, two different families, both tracing their ancestry back to Heracles. Purportedly at some time, very early in Spartan history, a king had twin sons and the kingship was divided between them and so you have the uaponted house and you have the ageid house. Sparta almost certainly begins as two bands of raiders led by chieftains, each of whom claims to be of Heraclid derivation. Around 750 there appears to have been a kind of rebellion by the notables within Sparta and what you get out of that is the establishment of a council of elders.

It’s called the Gerousia and Gerousia has the same root as geriatric or gerontology, it refers to old people. In the period where we know a lot about it, you have to be 60 years old to be eligible for election to the Gerousia and it’s drawn from certain families in that period which suggests that there is a time in which a balance is established between a spartan aristocracy, an aristocracy within the Spartan community and the two kings later and there’s an office that is used to check the king that is called the effort. The eforoy, they are called and there are five of them, perhaps one to each of the constituent villages of Sparta, but maybe not that way in the beginning and in fact maybe there are only three in the beginning representing the three ancestral tribes of the Dorians.

There some indication there, spartan colonies that only have three efforts, which suggest that very early on there were only three and that suggests that they are drawn from the well born within these three tribes, these three Dorian tribes. But by the middle of the 7th century, the there seemed to be five efforts which would fit the five constituent villages and there appears to have been a kind of democratic reform. One that left intact the Gerousia, changing nothing there, left intact the kingship, the two families, but took the effort and democratized it and there’s reason to think this takes place in the 7th century in connection with a military reform that takes place in which you have the emergence of the hoplite Phalanx. This is built on a particular piece of equipment called the aspice and sometimes called the hoplon, which is carried by a hoplite, and what it is it’s a large circular shield of the sort that people see on Greek vases, for example and at the center of the shield is a hook.

You put your left arm through that Hook and you carry the weight on the left arm based on that Hook and a hook on the right rim of the shield. So you have your arm through the hook in the middle of the shield and you grasp the hook on the right side of the shield. And if you think about this, this is a shield that will cover your left side but not your right side. And so it’s a shield that’s only good in a phalanx where the man next to you in the battle line holds a shield that covers your right side and his left side. The shield would be disadvantageous in ordinary fighting because it leaves your right side uncovered and it’s very hard to make use of that shield to cover the right side. So it seems to be designed for a particular military formation and that’s the hoplite Phalanx.

Well, the strength of the hoplite Phalanx depends to a very great degree, it’s an infantry Phalanx, just, it depends to a great degree on the number of people in it. So what you want to do if you’re forming a hoplite army, is to maximize the number of people in the battle line, in the battle line of the Phalanx and it’s eight men deep in the standard battle line. So if somebody gets killed, somebody else shoves in to replace them in the position that they hold and here’s the virtue of the hoplite Phalanx. A cavalry charge can’t affect it because the horses will not go through a shield wall. They will rear, they will pull back, you can’t get a horse to do what human beings sometimes do, bang their head against a wall.

A horse that is a blind, a horse that is mad with the pain, might plow into a phalanx, but the other horses, they’re going to veer away from it. So you form this shield wall and you’re pretty much impervious to cavalry except on your flanks and of course if they come at you from behind. Then the battle is actually like a rugby scrum with shoving and pushing and something, you don’t get in a rugby scrum at least ordinarily stabbing and killing and y need manpower for this to make this thing work whereas the old manner of fighting suggested in homer may involve cavalry that at certain points dismount. Horses are very expensive, it’s like owning a Porsche so the cavalry warfare is the warfare. They’re wealthy in all human periods. Infantry warfare, especially the kind that you see with the hoplite phalanx is the warfare carried on by ordinary men and quite naturally, if you’re going to fight for your country, you’re going to want to have a say in the decisions of whether to go to war or not.

So there appears to be at Sparta, a constitutional change that takes place 650, somewhere around that time, then the whole thing is pretty much set. So what you have is a monarchical element with the two kings and aristocratic element with the Gerousia elected from among certain families, and the democratic element with efforts who seem to be, at least according to Plato, chosen by some sort of method that has kinship with a lottery to represent the common people. The final element in it is there is an assembly. And in that assembly it’s one man, one vote. So it’s a mixed regime and different elements in it have different powers. For example, once a month the kings get together, the two kings with the five efforts, and the king swear they’ll uphold the laws and the effort swell swear that they will uphold the power of the kings as long as they uphold the laws.

There’s a thread in that and we know that in the 5th century, I know of only three kings in the 5th century who are not known to have been put on trial by the efforts on a capital charge. So there’s, there’s a lot of infighting that goes on within the spartan constitution and it seems to turn on the two kings and the evidence we have mainly from the 4th century suggests that each king has his adherence. It’s almost as if you have a two party system, one representing the appointed line in the other representing the aged line, and the trial if a king has tried, takes place before a court made up of the efforts and the Gerousia.

There are 28 members of the Gerousia plus the two kings and their five efforts so the Gerousia plays a crucial role at that point. And when the assembly meets, it’s the Gerousia working as a you to council that sets the agenda for the assembly. So it’s a very complicated political system and its function seems to be to prevent anything from happening unless there’s consensus and to produce consensus. And the agoge in the Spartan way of life is also aimed at producing consensus. There should not be at Sparta any kind of competition for wealth because everyone is provided for within allotment, a farm by helots and the city provides them with that so the kind of competition that comes from a difference of economic interests would be eliminated. The kind of competition that might come from religious interests is eliminated because they all share a common religion, it is a religious community.

The kind of competition that comes from a difference of opinions is restricted because they receive a kind of indoctrination during the agoge from age seven to 18 and they live in a highly communal setting because of the sesedia. What competition is left? Well, the rivalry for honor and for glory and of course the rivalry between the two royal houses.

Brett McKay: I’m curious, during all these reformations that happened to establish these checks on different groups, did Lycurgus, was he a real person to deep play a role? Was that. Or was that just sort of a myth that was invented?

Paul Rahe: Well, again, I don’t think anything is very likely to be completely invented, but there may be accretions. By the 5th century, if you asked a Spartan what did their form of government come from and their way of life, they would say Lycurgus did everything, but we have other evidence suggesting that the kingship goes way, way back, that the Gerousia and perhaps three efforts go back to about 750 and there was a list of efforts of the lead effort, of the eponymous effort after whom the year was named. They don’t give numbers two years, they named them after the eponymous effort goes back to about 753, that suggests that change. At some point there clearly was a change from three efforts to five efforts and that seems to come with Hoplite warfare, so who was like Lycurgus? The most likely answer is he is the figure, a member of the royal family of one of the two royal families, but not in line to be a king, who led the aristocratic opposition that produced the Gerousia.

In other words, if you look at what we’re told about him, clearly there are accretions, that is to say things are attributed to him that couldn’t have been done by one person because they’re done at radically different times, and the legendary character of him, the fact that he’s kind of lost in legend suggests that he lived early and the likely time is about 753. We are told a story in Plutarch which is almost certainly derivative from Aristotle’s constitution of the Lacedemonians that points to that early period and to his connection with setting up the Gerousia and that makes perfect sense. And the later changes with regard to the effort, there are sources that attribute those to two Spartan kings acting in cooperation with one another, and eropaunted and an aged and we can date those spartan kings and a rough and ready way to the first half of the 7th century.

Brett McKay: So Sparta had a very pretty sophisticated political regime setup. How long did it last?

Paul Rahe: Well, it depends on what you mean by lasting. The Spartans are rather successful from about 750 down to 320, 362, excuse me, BC and actually a little before that, say 371 BC and the foundation that emerges that allows them to be such a force is their conquest of Messenia. So they have all this land and they have all of these laborers which allows them to articulate their way of life and to be a military power, you deprive them of Messenia, which is what the helots under Epaminondas did in the second quarter of the 4th century BC, you deprive them of Messenia, and in the process you are undermining their capacity to put an army of any size into the field and they never really come back after 371.

If you mean by their way of life and Laconia. And as a kind of backwater, something like Disneyland, it survives into the later Roman empire. So there’s a strong tradition there, there are helmets in Laconia and there are small number of Spartians, many, many smaller than there had been in the 5th century and they continued to lead a life of leisure dedicated to hunting and gymnastics and so forth, but they’re completely inconsequential. One of the reasons that that Sparta, the Sparta of the helonistic period and the Roman period is not destroyed, is why bother, they’re inconsequential. It’s a kind of relic of an earlier age, but the real thing is over at when Epaminondas frees Messenia and it is confirmed at the battle of Messenia in 362 when the Spartans try to make a comeback and they fight the battle to a stalemate.

So nothing changes, Messenia remains independent, Arcadia, which is to the north of Sparta, had been organized into a league by Epaminondas and a city established to the northwest of Sparta, sort of between an area to the north of Sparta and Messenia, between Sparta and Messenia. In other words, to the north of Mt. Taygetus, at a place called Megalopolis the big city, that remains too. So it’s pretty much done for the Spartans in 371 and their attempt at a comeback in 362 fails.

Brett McKay: So it was about a 400 year run?

Paul Rahe: Yeah, which is pretty good.

Brett McKay: It’s pretty good.

Paul Rahe: We haven’t made it 400 years yet.

Brett McKay: We haven’t made it yet and now we’ve got a quite a while to get to that point. Throughout this conversation you’ve been talking about, and I’ve kind of slipped into it to where we praise and we feel like we have the most in common with Athens, but what’s interesting, and you mention this in your book, is that Sparta figures much more prominent in our popular culture. Like I said at the beginning, we don’t make movies or write books about Athens really-

Paul Rahe: Not so very many.

Brett McKay: Not so very many. And even if when we do, they’re not that popular compared to the ones about Spartan. Like Steven Pressfield who is a novelist, fictional accounts of Athens and Sparta, he did one about the battle of Thermopylae with the gates of fire and the 300 and that’s got over 1500 reviews on Amazon. Then he has a novel that centers on Athens and that only has, Tides of War, that only has 182 reviews. We feel like we have more in common with Athens, but we actually … when we make our choices about what we want to watch or read, it’s about Sparta?

Paul Rahe: Or what we want to name our football teams after. I’m in Michigan here and Michigan State has the Spartans and I wish that they would invite me to give a lecture during halftime at a Michigan state game about the real Spartans, but they haven’t done that yet. I haven’t even been invited to give a talk on Sparta at the university proper yet. Someday it may come, someone may think, Gosh, we really ought to do this, but it’s Thermopylae that gives the Spartans their sort of cultural leverage.

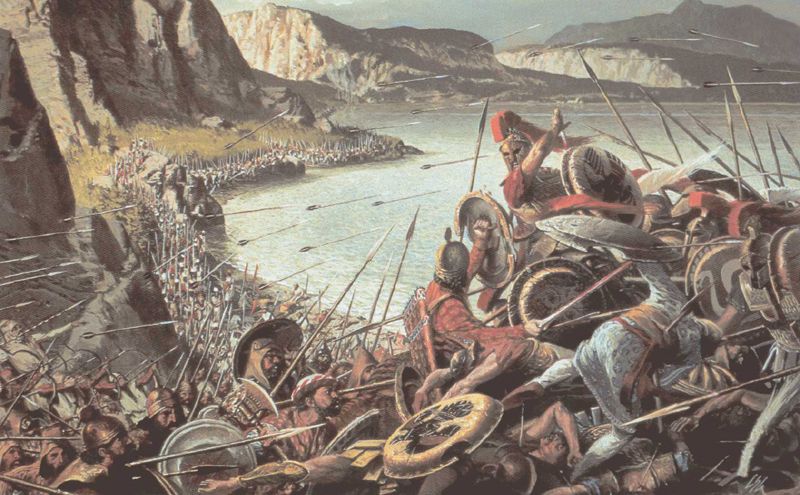

You have 300 men who fight to the death against an invading Persian army knowing perfectly well that they’re going to die and this impressed the Greeks, it actually impressed the Spartans back home a lot. It set a standard for them that it was hard to live up to and it impressed the Greeks enormously. The Athenian victory at Salamis was extremely important, but it didn’t impress the Greeks as much as the Spartans’ willingness to die at Thermopylae in the way they did. And their relative success in stopping the whole Persian army at a choke point, until Xerxes sends 10,000 Persians around the mountain to get behind the Spartans. That story is very, very powerful.

If you look at the public schools in Britain, they weren’t modeled on Athens, they were modeled on Sparta. If you think about the United States marines, they’re not modeled on Athens, they’re modeled on Sparta so it’s odd. Within a bourgeois society organized around commerce, around sort of global trade and so forth that more nearly resembles Athens we still don’t think first of Athens. The scholars do, the literature on Athens is probably a thousand times as great as the literature on Sparta, the secondary literature, and until I started writing these books on Sparta no one had ever written more than one volume on Sparta.

It was sort of an anthropological oddity from the perspective of the scholarly world and so people would write a single volume sort of describing Spartan institutions and Spartan practices, but to actually look at their history and to study the situations they find themselves in and how they cope, there’s very little on that, everything is ethnocentric. But in the popular world, Sparta is more of a focus than Athens or even Rome really.

Brett McKay: You’re working on a series of books about Sparta. There’s the spartan regime, and then there’s the grand strategy of classical Sparta is there any more coming out in this series?

Paul Rahe: Yes. In next September, Yale University press will publish Sparta’s first addict war, the grand strategy of classical Sparta, 478 to 446 BC. That book is in pres now, it’s been copy edited, it is about to be sent into production, which means they’ll produce a page proofs. There’s a book coming after that, it is been accepted for publication by Yale. It is called Sparta’s second attic war, the grand strategy of classical Sparta 446 to 418 BC. The first of these two volumes is about what scholars have called the first Peloponnesian war writing from an Athenian perspective, it’s the Peloponnesian war, but which at the time was called by people in the Peloponnesus, the first attic war.

The second volume is about what scholars call the great Peloponnesian war, Thucydides’ Peloponnesian war, and it’s about the first 14 years of that war and the onset of that war, which was called Sparta’s second attic war. So I’m following … I’m trying to look at the world through Spartan eyes and that’ll come out in September 2020.

Brett McKay: Well Paul, this has been a great conversation. Thanks for coming on.

Paul Rahe: My pleasure.

Brett McKay: My guest today was historian Paul Rahe, he is now working on a series of books about ancient Sparta. You can find two of them right now, The Spartan Regime and the Grand Strategy of Classical Sparta on Amazon. Just look at Paul Rahe, that’s R-A-H-E, and he’s got a few more coming out in this series so be on the lookout for that. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/sparta, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the art of manliness website @artofmanliness.com, and if you enjoyed the show, you’ve gotten something out of it, I’d appreciate if you’d take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. That helps out a lot and if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with your friend or family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for your continued support and until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.