You’ve probably heard of the “Most Interesting Man in the World.” He’s the popular Dos Equis brand-spokesman who’s lived a life of adventure, has great stories to tell, and feels comfortable rubbing shoulders with the common and rich alike.

Of course he’s a fictional character made up by clever ad executives.

But back in the late 19th century there was a real-life guy who would put “The Most Interesting Man in the World” to shame. In his own time, he was known the world round, yet hardly anyone has heard of him today. Well, we’re going to help change that with this installment of the podcast.

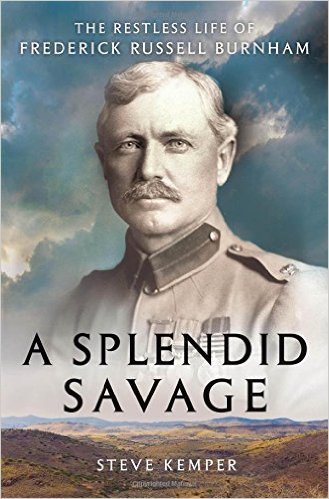

Today on the show I talk to writer Steve Kemper about his book, A Splendid Savage: The Restless Life of Frederick Russell Burnham. We discuss the adventures and world-wide exploits of the military scout, prospector, and real-life inspiration for the Boy Scouts, as well as what men today can learn from this “splendid savage.”

Show Highlights

- How Frederick Russell Burnham was literally born in fire on the Minnesota frontier [04:00]

- How Burnham’s childhood experience with the Sioux influenced the rest of his life [06:00]

- Why Burnham stayed behind in California by himself when he was just 12 years old while his family moved back to the Midwest [06:30]

- Burnham’s teenage schooling under some of the most famous and skilled mountain men [07:30]

- The extreme measures Burnham took to train himself to be a scout [10:00]

- The books Burnham read as a child that inspired his romantic quest to become a great frontier scout [11:00]

- Burnham’s involvement as a teenager in the Apache Wars and America’s bloodiest family feud [14:00]

- The beginning of Burhman’s career as a gold and minerals prospector [19:00]

- The kind of woman who’d marry Burnham and follow him on all his adventures for the rest of his life [22:00]

- How Burnham fulfilled his childhood dream of scouting in Africa while getting right in the mix of the Boer Wars [26:00]

- How the Boer War made Burnham a household name world-wide [32:00]

- Burnham’s prospecting in Africa [33:00]

- Burnham’s prospecting in the Klondike [35:00]

- Burnham’s famous, rich, and powerful friends, including Teddy Roosevelt and Winston Churchill [36:30]

- Did Burnham make up his adventures and exploits? [40:00]

- How Burnham helped inspire the Boy Scouts [41:00]

- Why hardly anyone knows about Burnham today [44:00]

- Burnham’s prospecting in Mexico and how he helped thwart an assassination attempt on President McKinley [45:30]

- How Burnham finally became wealthy in the oil fields of Los Angeles after a lifetime of prospecting the entire world [46:00]

- What drove Burnham’s quest for adventure his entire life [47:30]

- What men today can learn from the life of Frederick Russell Burnham [49:00]

Resources/Studies/People Mentioned in Podcast

- Dakota Sioux War of 1862

- Sioux wisdom on becoming a man

- Sioux warrior toughness training

- Dime novels

- Apache War

- Tonto Basin Feud

- George Crook

- Jack London (my podcast interview with London biographer Earle Labor)

- Klondike Gold Rush

- British South African Company

- Matable War

- Boer Wars

- The Boers

- Cecil Rhodes

- Winston Churchill’s Guide to Adulthood

- H. Rider Haggard

- Lord Baden-Powell

If you’re a history buff, you’ll definitely enjoy A Splendid Savage. If you’re looking for a kick in the pants to start living a life of adventure, this book is for you too.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Carnivore Club. Get a box of artisanal meats sent directly to your door. Use discount code AOM at checkout for 10% off your first order.

Fulton and Roark. Check out Fulton and Roark’s new aftershave wipes. Use discount code “ARTOFMAN” at checkout for 15% off any purchase of $20 or more.

Freshbooks. FreshBooks is offering a month of unrestricted use to all of our listeners totally free right now. To claim your free month, go to FreshBooks.com and enter “Art of Manliness” in the “How Did You Hear About Us?” section.

Five Four Club. Take the hassle out of shopping for clothes and building a wardrobe. Use promo code “manliness” at checkout to get 50% off your first box of exclusive clothing.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here. Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. We’ve probably all seen that the Dos Equis’ most interesting man in the world commercials. A guy goes on great adventures, has great stories to tell, is friends with the rich and famous. He’s a fictional character but here’s the thing, there was a guy in the 19th Century that would put the most interesting man in the world to shame.

His name is Frederick Russell Burnham. He was a world’s famous scout that did time with TR and the great mountain men of the American West. Not only scouted in America, and took part in the Apache Wars, he went over to Africa for some adventures and took part in the Boer Wars that were going on over there in Colonial Africa. All the time prospecting for diamonds, oil, gold, you name it. He was doing that on the side as well. He went to the Klondike to do some prospecting there. He went to Mexico to go on some adventures and take part in some of the hijinks of the Mexican Revolution.

He also was friends with some of the most influential men in world history. Teddy Roosevelt was a close friend of his. He was friends with some of the big capitalists of the day. Friends with Lord Baden-Powell, the Founder of the Boy Scout Movement. In fact, as well, see, Frederick Russell Burnham had a significant amount of influence on the Boy Scout Movement.

Anyways, lots of stories on this guy. There’s a new book out about his life. It’s called A Splendid Savage: The Restless Life of Frederick Russell Burnham. The author is Steve Kemper, and I have him on the show today to discuss this guy who’s not only many people know about him today but he’s lived in amazing life. We’re going to talk about his stories. He’s a complex character. He’s a product of his times, why he went on all these adventures, what was driving him, and what we could possibly learn from him. Without further ado, Steve Kemper, a Splendid Savage, Frederick Russell Burnham. Steve Kemper, welcome to the show.

Steve Kemper: Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: You wrote the biography of what … I’ll go out there and say, he’s quite truly the real life most interesting man in the world. His name is Frederick Russell Burnham. He was a famous scout, prospector. This guy did it all. We’re going to get into his exploits that he did during his life, but let’s start from the beginning because his life was interesting from the very beginning. He was born in the Minnesota Frontier. Figuratively and literally, he was born in fire. Can you tell us a little bit about Burnham’s early years in the Minnesota Frontier and hos his experience with the Sioux Native Americans, in particular, formed the foundation for the rest of his life?

Steve Kemper: Sure. He was the son of a preacher man who was a very educated guy who took a lot of higher education from the east, and went to a Winnebago Indian Reservation on the Minnesota Frontier, and that’s where Frederick was born. His timing, as usual, was impeccable for trouble. A year and a half after he was born, the Dakota Sioux started a war when a lot of the men were with our Civil War.

One of the consequences was they attacked Burnham’s homestead. Burnham’s father was away trying to get some lead to melt down for bullets. Burnham’s mother was there with him, and she saw them coming, and she picked him up and ran. She realized “If I keep running with this baby, they’ll catch us both and kill us both.” She stuffed him in a shack of green cornstalks, and kept running, and told him not to move. The next day, she came back. He homestead was burnt down, cornstalks are scorched in a few parts here and there. Lying in there quietly is her son, Frederick Russell Burnham. That was his introduction to frontier life and Indian warfare.

Brett McKay: Beyond that introduction, that initial introduction, did he encounter the Sioux later on his childhood or I guess, at one point, his family moved to California.

Steve Kemper: The settlers in Minnesota, and it really was a frontier. It’s just a few edge of the frontier. It was turning into something else by the time Frederick was born. They kicked all the Sioux out and killed some of them but made the rest go to reservation. There were no legal Sioux there for Frederick’s early childhood but there were plenty of other Indians around. He played with them, all the children did. That’s partly he stated his interest in woodcraft in Indian ways.

You’re right. Then, they moved to California because his father got sick. They want to go to a new place, a warmer place in hopes that it would help his health. It didn’t. He died when Frederick was 12. The mother and Frederick’s younger brother decided to go back to Iowa because they had no means of making a living. Fred said, at age 12, “No, I am going to stay. I am going to be fine down here.” That’s what he did.

Brett McKay: That was amazing. The reason he stayed behind is he wanted to pay off his mother’s debt because I hear she had to borrow some money to get back to Iowa because their family was destitute. Here’s this 12-year-old kid saying, “I got to take on my family’s obligation.” He started doing these odd jobs around California. Then, he ended up traveling around the southwest. This is the time when the southwest was the Wild West. What kind of work did Frederick do during this time and what skills did he acquire with the jobs that he did that helped him later on in his career as a scout?

Steve Kemper: He started at age 12 as a messenger of Western Union Telegram. He delivered telegrams from the inner city of the pueblo. Los Angeles was really small at that time with less than 10,000 people. He did that 16 hours a day delivering telegrams to ranches and villages outside of the pueblo.

He got tired of that because it was regimented and he became a freelance hunter for freighters camps in the mountains of California. The freighters were hauling silver and lead bullion from the mines in the mountains of California to Los Angeles which became the ornaments of the Gilded Age eventually. All the guys who were on the wagons needed to eat and Frederick learned it was a good shot, and he was a horseman. He earned a living by hunting for supplying meat to these camps.

In that meantime, he also met some of the old frontiers and some of the old Indian fighters from earlier campaigns and began picking their brains about how to read tracks, how to follow a horse, how to know what the size of someone that you’re tracking, the number in their party, how to avoid being picked off and killed by someone who is looking for you. All these skills he began to pick up as a youth in the southwest.

Brett McKay: That was amazing. He had this great apprenticeship during the southwest period. It was interesting. Did he seek these mountain men out or did he just somehow come across them, and he impressed these mountain men, and they took him under his wing?

Steve Kemper: My impression is that he sought them out. He had decided in Minnesota that he wanted to be a scout. He knew that from a young age. The people who were the repositories of this knowledge were, as you can imagine, gruff, ruff old timers who didn’t have a lot of patience for teenagers who wanted to ask a lot of questions. He basically had to hang around until they saw that he was serious, and that he had some talent, and that they couldn’t scare him off. That’s how he learned.

For Burnham, scouting, it was, I supposed, romantic in some ways but essentially, it was a very hard discipline that you had to practice every day and learn. A writer, later on, referred to him as the Paderewski of Scouting because he had devoted so much time, discipline, and work to doing the things that he could do out in the wild.

Brett McKay: His training was intense. He’s almost like a monastic warrior with some of it. I guess, one of the things he’d do, he’d prick himself with pins so he could learn how to withstand pain.

Steve Kemper: Yeah. He thought that a good scout had to be able to still function when he was exhausted, very thirsty, very hungry, and alone for long periods of time which for Burnham, that was the hardest part because your mind would start to play tricks on you. As we all know, if you’re alone too much, you become weird. There’s a fine line in between scouting and staying alert and scouting as psychopathology. He knew he had to thread that line.

Brett McKay: You said that his desire to become a scout, there was some romantic notions to it because, I guess, Burnham, like a lot of young boys growing up in Victorian England and America, he read and devoured these adventure books written at the time. These are the same books like Teddy Roosevelt read as a boy, Winston Churchill. Can you tell us a little bit about this adventure genre of Victorian Anglo world, I guess we’ll say, that inspired Burnham and a lot of other young men to become adventurers?

Steve Kemper: Yeah, it’s a symptom of both the expansion west and the early symptoms of its ending because that’s when you become nostalgic and romantic about these things, but these books became very, very popular in the 1860s. Most of them were highly embroidered biographies of frontier heroes such as Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, and Kit Carson.

This is also the decade and the era when dime novels became available everywhere, and they weren’t expensive, and had wide distribution, and these were just unbelievable fantasies where heroes had names like Deadwood Dick, and Mustang Sam. The titles were things like The Scalphunters, or Search for a White Buffalo, or Steel Coat, the Apache Terror. Of course, the boys can eat this stuff up. I did. When I was a kid, I loved those old frontier stories and things.

Burnham was reading these as a child in Minnesota and thinking, like any kid would, “Wow, I would love to be out there with the Apache terror, and the white buffalo, and Deadwood Dick.” There’s a romantic side of this. Then, you get out there and you realize it’s the Wild West. It’s Indians who want to kill you. It’s rough manners trying to scratch a living, most people failing. There’s a lot of alcoholism, and none of this stuff appeared in the books.

Brett McKay: Right. Also, the scouts in the books often appear to be … Burnham even talked about this in his writings that as a child, he read about these scouts in the Wild West that you just solve things or like Sherlock Holmes but he says, actually, the job of the scouts were really tedious, and boring, and monotonous.

Steve Kemper: Yeah, because you’re sitting on a rock waiting for something to show up, or move, or reveal itself so that you can report back, and yet to stay constantly alert because somebody is looking for you too to move and find out what you’re doing, and the plans that you have to take. It’s all about preparation, patience, being able to bear all these hardships, and bring back information that’s valuable to your commander. It’s not for everybody.

Brett McKay: Yeah, but Burnham had that drive. Speaking of this, you read these stories about the Apache wars. Burnham actually got involved in some of the Apache conflict that was going on in the southwest, as well as this feud that he had no idea that happened during the Wild West that was bigger than the Hatfield and McCoys. Can you tell us a little bit about Burnham’s involvement with not only the Apaches but this family feud that was going on?

Steve Kemper: Sure. We still haven’t even gotten him out of his teen years.

Brett McKay: Right, still a teenager. This is a crazy thing, he’s still a teenager and he’s done all this stuff.

Steve Kemper: Yeah. The Tonto Basin Feud, it’s the bloodiest feud in US history and it was a ranch war, essentially, between sheep men and cattlemen in this isolated part of Arizona which was the most isolated part of America at that time. It was the wildest part. It was the last part that was settled. It was the last state let into the union because it was so wild. That’s where the Apaches were to, the Chiricahua and the White Mountain Apache. This is their stronghold as well.

It was very volatile. The Tonto Basin Food, there were two main families, and all the men on both sides were killed except for the one last guy who killed the last guy on the other side, and got away with it. He went to trial twice but got off because he had good lawyers. He was funded by the wealthy sheep man. Burnham was associated with this. He got sucked into it as everybody did in Central Arizona because you either were for one side or the other, or you had to have allies or you’re going to get killed. Burnham was forced to choose, and he did, and he was on the wrong side, and he was chased a few times, I guess. There was a price on his head but he got away and lived. There’s that.

The Apaches, he admired the Apaches very much. They were, for him, exemplars of scouting because they had armed bodies, they had armed wills, and they knew everything about their environment. They could survive in any conditions. They could disappear. As George Crook, who is the best fighter against them, he called him the tigers of the human species because they were such great guerrilla fighters. Burnham admired them very much even though he fought them.

This is one of the things about him. His attitudes were based upon the perspective from the saddle, not from the armchair. I try to keep that in mind when he’s doing some of the things and saying some of the things about native people in his life.

Brett McKay: It was the contradictions that he had. We’re going to be talking about this. he’s a guy filled with contradictions but like a lot of 19th Century Americans, he had these ideas about native people and white people, superiority of the white race, but at the same time, he respected not only Native Americans but he went over to Africa. There was a lot that he admired about the Native Africans there in Colonial Africa. At the same time, he had this disdain for them as well. This was something, I am sure, that it wasn’t just him. It was like Winston Churchill. Theodore Roosevelt even had the same attitudes. This mixture of disdain and admiration.

Steve Kemper: Burnham, he made strong choices. He admired the Apaches. Other Indians, he did not care for very much. He admired the Apaches because of their military culture and their absolute devotion to physical fitness, self-reliance, self-discipline, war, hunting, camouflage, scouting. Other Indians weren’t that way. He didn’t care much for them.

Africa is the same thing. The Ndebele Tribe, he admired very much because it was a warrior culture. They were incredibly brave. They were incredibly fit, devoted to mastery of their art which was war. Other tribes, he didn’t care for much.

He thought he was on the progressive side of history. It didn’t matter what qualities these other people had because if they were inevitably, in his view, going to be churned up by the progress of the white race which was the march in history which was inevitable, and he was glad to be doing his bit to make it happen. He was a racist but he was also a progressive. It’s not a contradiction in the mind of people like Roosevelt, Churchill, and Burnham.

Brett McKay: Right. That’s a mentality that’s really hard for modern Americans to understand but I think you did a good job explaining the mentality that why they would have that mentality. This is time that of the desert southwest but what’s interesting too, while he’s doing all this scouting in the southwest, he caught gold fever. This was something that would chase him the rest of his life. How did his scouting and prospecting were in tandem with each other?

Steve Kemper: That’s a good question. He was always after money as well. He’s always after that.

Brett McKay: He’s always after money. You know what, he reminded me of Jack London a little bit. Jack London was always after money. The reason why he wrote all these books was so he could have money.

Steve Kemper: Yeah. He was up there in Klondike. Burnham, he mentioned him, I believe, but I don’t know if they actually knew each other when Burnham got up there but you’re right, he wanted action and he wanted income. Those two things often drew him to the frontiers because that’s where he could find the action and you might find a bonanza because you were one of the first ones in. it hadn’t been rigged over yet.

I think there’s that excitement and there’s also the risk, of course, of both scouting and mining. You’re taking a huge risk. You’re going in unknown territory. You don’t know what you’re going to find. You don’t know if it’s going to be good fortune or failure. Both of them require knowledge of landscape and being able to read it for signs of what should and shouldn’t be there. You have to know how to spot the signs of gold or silver if you’re going to be a miner.

Then, you have to be able to track those because usually they appear as what’s called float, just loose stones that have flakes of gold, or veins, or remnants. Then, you have to figure where do this come from. You have to track it back to the vein where they eroded from or the load of where it came from, and see if there really was anything there or if it’s just going to be another empty hole. I guess, there’s some similarities between the two things.

Brett McKay: During this time, I guess, was he making his own claims during this time when he was scouting the southwest?

Steve Kemper: He didn’t want it and then he did the other. He alternated. He would need money so he’d kept going into the desert to look for things that would give him a paycheck. Sometimes, that was as a hunter for mining camps and sometimes, it was as a prospector. Then, if a war broke out and Apache uprising occurred, he would get himself hired on as someone who could help do that. He was still very young when the last Apache campaigns were held but he learned from some of those old scouts for crook and kept mastering, and learning, and developing that. That’s what he took to Africa with him when he finally felt like the west was getting too hemmed in, and he had to go someplace new.

Brett McKay: He’s done this, he’s still in his 20s, early 20s. What’s interesting though was this is a guy who was filled with wanderlust, desired action, but the guy still got married. He was married to the same woman his entire life. Can you tell us a little bit about his wife, Blanche, and the type of woman she was? Why does she put up with Burnham? Because it seemed like she liked that he was so action-oriented, and then he took her on these adventures, but at the same time, you could tell in her diary and her letters that she just wanted to settle down. Why did she stay with Burnham for their entire life?

Steve Kemper: That’s a really good question and the only answer is that completely illogical one, love. It makes people do crazy thing. They really loved each other. This is a love story, there’s no doubt about it. She liked the excitement that she brought to his life. She wanted to travel with him. I don’t think she wanted to settle down so much as she just wanted to be with him because she went with him all over the globe in some pretty rough places, and liked it.

In fact, she got impatient in London just like he did and said, “I want you to take me to Patagonia. Let’s get out of here and go do something remote,” but often, Burnham was away because these places were often no place for women or he was at war, and that was no place for a woman at the time. She penned for him and he penned for her too, but it didn’t stop him from going.

That’s one of the contradictions in him, I think. Their letters were filled with longing for each other. Romantic love all the way to the end. It’s an amazing thing. They did finally when Burnham was in the ‘60s get to start spending their time together.

Brett McKay: He gets married early 20s, decides to fulfill his childhood dream of going to Africa because things in the Wild West were just not wild enough for him. Again, so it seemed like in Africa, Burnham had two things going on the same time. He had the scouting and prospecting going on at the same time. Let’s talk about his scouting first. Who was he scouting for? I think you had to like dig in deep into colonial African history first because this was completely new to me when I read your book. Who is he working for down in Southern Africa?

Steve Kemper: It was a British South African Company which is what they called a chartered company. The British Government had given a charter to the British South African Company to settle and man a vast section of Africa which these days is known as Rhodesia and it encompasses some of the other countries near Rhodesia which is now Zimbabwe.

Burnham wanted to go there because this was an exciting new frontier. He wanted to help the white raise progress, and he wanted to make money, he wanted to prospect. Southern Africa had made millionaires of a number of people because of the diamonds for coming out of South Africa and the gold, the famous Rand and the famous Diamond Mines of the De Beers. They were booming and Burnham thought, “I want some of that.”

He goes over there for that. Just as he reaches the settlement, and there were only two little forts at that time in this part of Africa. Just as he reaches there, war breaks out with the natives. Instead of becoming a prospector, he has to become a scout. He and another American and a Canadian were the three main scouts for the settlers, the militia that went to war against this very powerful kingdom of black warriors of the Ndebele tribe. They won because they had a gun that could mow down the natives. It’s one of those things where a few hundred people can dominate thousands because of artillery, guns, drums, and steel.

Brett McKay: Yeah. He had his skirmishes with the natives but then, there’s these fights and wars with the Boers can you tell us a little bit about the Boer Wars and Burnham’s involvement with that?

Steve Kemper: Sure. Just a little bit more background, they won that first war against the natives. Another war broke out against the natives. The natives rebelled eventually. Naturally, they tried to take back their land. Then, Burnham went to the Klondike. Then, when he’s in the Klondike, the Boer war broke out in Southern Africa.

The British were getting there behind, handed them by the Boers who were terrific guerrilla fighters because they knew the landscape. They’ve been there for a long time. The British were arrogant. They marched in solid blocks of land that were used in the mow-down. They had no intelligence. They didn’t have military intelligence. I guess, it’s the same thing as intelligence in war, isn’t it? You have to have one or you don’t have the other.

The commander of the British Troops, Lord Roberts, heard from one of his officer, “The best scout I ever had was this American guy named Burnham. I think he’s on the Klondike. Let’s see if we can find him.” Lord Roberts sends a telegram and gets to Skagway. Burnham, he gets it. He comes home and tell his Blanche, “We’re leaving in two hours. I’ve been appointed Chief of Scouts for the British Army in Southern Africa.”

That’s how he got involved in the Boer War and that’s where he became really famous. He’d done some exploits before that in the famous events in the native wars, but the Boer War is what really brought him to world attention and kept him there co he was behind the enemy lines over a hundred times. He was always doing things that were extraordinary and surviving them. He got captured, he escaped, and then he’s blowing out railroads, and that sort of thing. He became very well-known. He was in the London papers a lot at that time.

Brett McKay: Yeah, not just London. He also made his way over to America in the New York Times. His exploits would be there too.

Steve Kemper: Yeah, yeah. He was well-known but, of course, most Americans were for the Boers in that war, not the British. He was well-known but he was not as appreciated as he was in Britain, I guess, you could say by some people.

Brett McKay: For those who aren’t familiar with the Boer Wars, the Boers were, I think, Dutch Settlers that had settled their first in Southern Africa. Is that right?

Steve Kemper: Yes, that’s correct.

Brett McKay: Right. It was like Europeans fighting Europeans.

Steve Kemper: Yeah. It was the white men’s war, they called it. Of course, a lot of black people had to pay the price for the white men’s war but it was a horrible, horrible, war. It was very costly to the British. It was terrifically costly to the Boers who were the equivalent of the Apaches in some way, the small group of mobile guerrilla fighters taking on an empire. They held the British Bay for years and years. The British drained them. It was like their Vietnam. It also was the beginning of concentration camps and of trench warfare. It was things that the 20th Century adopted and were horrified by in the First World War but it happened first in the Boer War.

Brett McKay: Burnham gained world fame, I guess, after the Boer War. He and his wife, they went up to London. They had to entertain all these dignitaries. I think even Queen Victoria wanted to meet with him but she had to cancel for some reason.

Steve Kemper: Yeah, she got sick and that’s why she canceled. Burnham was awarded the Distinguished Service Order which is the highest medal that a foreigner can receive in Britain, and he received that from King Edward the VII because of his actions in the Boer War.

Brett McKay: While this was going on, in between these times that he scout when he was in war, he’s also doing prospecting in Africa. How did his prospecting in Africa turned out or was that a bust?

Steve Kemper: I guess, it depends on how you look at it. He discovered many very wealthy veins and rifts, they’re called, of gold, veins of copper, a lake of sodium carbonate that he thought all these things were going to be his fortune because they were so fabulously wealthy and he was partners. He never wanted to just be on the payroll. He wanted to have a percentage because he was an entrepreneur and a risk-taker.

Then, things kept getting in the way. Sometimes, another war would crop up so that you couldn’t get to the veins, or his partners would run out of money and they wouldn’t develop the veins, or his partners would screw him so he couldn’t get the money that he deserved to get. It’s really incredible how tantalizing so many of these things were that he did the work for, and then never cashed in on, but he did do well enough to save enough money so that his children can be educated and so that he could take care of Blanche for the rest of her life, and Blanche’s parents, and his own mother.

He sent quite a bit of money back to the US just before the Boer War. He had enough mining interest and land interest to do that. He wasn’t fabulously wealthy. He just was keeping his family above poverty. They knew that they would never have to live in poverty which is not the same thing as being wealthy.

Brett McKay: Right. Despite of being above poverty, he was world-famous.

Steve Kemper: Yeah, and his military staff, but that also made him attractive because he was successful at finding these mineral deposits. He was a mineral explorer. He was hired by syndicates to explore other places in Africa, the gold coast of Africa on the west coast which is Ghana. We call it Ghana now. He led an expedition there that was very successful in terms of gold but he never sow much money from that at all. Also, in British East Africa which is now Kenya, he found this soda lake and a lot of rich agricultural land, and he sow nothing from either of those things either.

Brett McKay: Let’s do a recap here of this guy’s life because we’ve only skimmed the surface. Almost got burnt by Sioux during the Civil War in Minnesota. Goes to California, as a 12-year-old boy by himself. He works for a Western Union delivering telegrams. Meets mountain men. Gets apprenticed by mountain men during his teenage years. Late teenage years, early 20s, he is taking part on one of the greatest, biggest feuds in American history, fights Apaches, gets married, goes to Africa, is a scout when these native wars for this charter company. Then, he goes to the Klondike to take part in the gold rush that was going on there. Comes back to be a scout during the Boer War. All a while in Africa, he is prospecting, buying property, et cetera. That’s a lot. He became world famous. By that time, he’s at his 40s, right?

Steve Kemper: Yeah, I think he’s in his late 30s in the Boer War.

Brett McKay: Yeah. What’s crazy too, this guy had some crazy adventures but during his life, he rubbed shoulders with some of the most influential people in the world during the late 19th and 20th Century. Who were some of the famous men that Burnham, this humble American scout from the Wild West, who were some of these men that he called friend?

Steve Kemper: For starters, it would Cecil Rhodes who was the main partner in the British South African Company who had this vision for Southern Africa as the next great outpost of British civilization. He became friends with Rhodes and even business partners with Rhodes. They were a lot alike in some ways, risk takers, the odds didn’t matter, the vision is what mattered. He knew Rhodes.

Brett McKay: Rhodes is the guy, the Rhodes Scholar is named after him, right?

Steve Kemper: That’s right. Rhodes was one of the wealthiest man in the world at the time that Burnham met him but he didn’t care much about the trappings of wealth. He was more interested in this vision of what to do in Africa, and how to turn it into this gigantic extension of British Civilization. He’s extraordinary. Rhodesia, of course, was named after Rhodes after the native wars. Then, Rhodes funded what became the Rhodes Scholarship because he also was interested in preserving some of the ruins that you found in Africa. They didn’t believe that that the natives had built them. They thought that maybe Phoenicians had come down and done it. In keeping with the racial attitudes of the days, it couldn’t possibly be a product of Negative Culture, and it was, of course.

He knew Rhodes. He knew Winston Churchill because of the Boer War. They were shipmates on the way back when Burnham, who had been severely wounded while he was blowing up a railroad and had to crawl back to British lands. He cut up the Canvass Gun Powder suction, put him on the sands so he could crawl back to the British lands. They were on the same boat back to Britain. Churchill had just escaped from the Pretoria Jail which is a famous episode in his life. They became friends.

He was good friends with H. Rider Haggard who was one of the most popular novelist of the day. He wrote things like She, and King Solomon’s Mines, and he said about Burnham, “In real life, he is more interesting than any of my heroes of romance,” which is quite a compliment.

Then, of course, Roosevelt. He met Roosevelt when Teddy Roosevelt was police commissioner of New York. They became good friends. Roosevelt asked him to become a Rough Rider but Burnham, at that time, was on the edge of the Yukon River waiting for the ice to break up so he could go down river to the gold. He couldn’t do it. Later on, he asked Burnham to be one of the 18 officers for his volunteer corp that was going to go to World War 1 but Woodrow Wilson, he towed that idea because he didn’t want Roosevelt to get any more publicity.

He was very good friends with him all his life and some of the big capitalists of the day, John Hays Hammond, the Guggenheims, Harry Payne Whitney, Edward Herrmann, the railroad baron. These were people that Burnham was in partnership with various of times. He knew a lot of well-known people, and they all admired him. One mutual friend of he and TR said that Burnham was the only man who could turn TR into a listener which is a pretty high compliment.

Brett McKay: Yeah. It’s amazing. It sounds like a story. Like someone wrote a story like it’s fiction right from the 19th Century. You’d see some movie like the Extraordinary League of Gentlemen. Burnham was like the real life, most interesting man in the world.

Steve Kemper: His life was so incredible that some people have called him a liar, by the way, and have said that he made stuff up. Of course, you can imagine I’m a reporter. This is pretty disturbing to me when I came across these allegations about some of the key events in Burnham’s life. I looked into this pretty hard. I must say that I found the evidence sent to nonexistent that he was a liar, that he made anything up. He did all this stuff. A lot of it is collaborated by contemporary accounts, his letters to all sorts of people, corroborate things that he was called a liar about. It is extraordinary. It is almost unbelievable that he did all these things but he did.

Brett McKay: Yeah, he was also friends with Lord Baden-Powell, the Founder of the Boy Scout Movement. This is interesting. Burnham actually had an influence on the scouting program. He specifically talked about some of the insights or influence that Burnham provided Baden-Powell when he started the scouting program.

Steve Kemper: Yeah, sure. He got to know Baden-Powell in Rhodesia during the Second Matabele War. Baden-Powell was an officer assigned there. The two of them went on, at least, one long scout together. Burnham appears in Baden-Powell’s book about the uprising. He was struck by how much Burnham could discern by just looking at what was around him.

This mesh with Bade-Powell’s worry that the boys of Britain were losing the masculine values that he associated with an outdoor life, self-sufficiency, resourcefulness, knowledge of nature, physical toughness, mental toughness. He thought that things should be preserved and he wanted to teach them, the boys, through some sort of organization. He talked about this with Burnham. Burnham said that, “That’s a great idea, you should do that.”

Eventually, as we know, Baden-Powell founded the Boy Scouts and other influence. They became really good friends. Baden-Powell, for decades, would write letters picking Burnham’s brain about woodcraft, and how to do things in the woods, and how to tell things, and read nature, and everything. Baden-Powell also, by the way, was an ardent advocate of scouting in military because he predicted that since the British had turned their backs on scouting, it was going to be disastrous militarily, and that’s exactly what happen in the Boer War.

Anyway, to get back to Burnham, Baden-Powell came to Southern Africa with the usual regalia of the British Officer that pit home at the Red Coat. Burnham said, “You need to take that off if we’re going scouting because you look like a target.” He adopted Burnham’s stiff, brimmed, brown Stetson hat and neckerchief. Of course, those two things became the main emblems of the Boy Scout uniform in later years.

Brett McKay: There you go.

Steve Kemper: I wonder if the motto came from Burnham too. I have no proof of it but, “Be prepared,” was certainly one of Burnham’s mantras. I wonder if he got that from Burnham.

Brett McKay: I’m curious if that happened too. Burnham lived a fascinating life. I am curious, why do so few people know about Burnham today despite being world-famous and all the stuff that he did during his lifetime?

Steve Kemper: That’s the vagaries of history and fame. There’s not a real answer that I’ve come up with about that. He just burned brightly and disappeared. He didn’t do anything that was extraordinary that made him stand out as a historical monumental figure. He just did his job, and seemed to be everywhere the action was. He knew a lot of famous people. I don’t know. Definitely, I think, he should be, at least, as well-known as Kit Carson and some of the other famous frontiers at US that we have.

I think that’s partly the answer. He was a scout at a time when those skills were not in demand or valued as much. He came after the miss myths of the scout. He was the real deal but he was after it. He missed the mythology. I’m just muttering on that. I don’t really know why.

Brett McKay: I think it’s a good theory. It’s a really good theory. How did Burnham spend his twilight years? Did he still have that itch for adventure even when he was 60, 70, 80 years old?

Steve Kemper: Yeah, I don’t think he ever lost that. He became wealthy, finally. We’ve left out in Mexico. By the way, they left at Mexico.

Brett McKay: Yeah, he went down to Mexico.

Steve Kemper: He got mixed up in that Mexican Revolution. At one point, he probably helps save President McKinley from being assassinated.

Brett McKay: He was a bodyguard for that big meeting between Diaz and McKinley at Wars in El Paso

Steve Kemper: Yeah, yeah. He did that but, anyway, in his later years, he started looking into oil, and became a partner with some wealthy people who trusted him to become a scout for oil. He said, “We need to dig at this place.” It was basically almost right outside downtown Los Angeles.

I don’t know if you’ve ever seen photos of Los Angeles in the ‘20s and the ‘30s but there are derricks everywhere. You could see them from any place in Los Angeles. A lot of people have drilled there already. His backer said, “No, I don’t want to do it.” Burnham said, “I know it’s there. I know it’s there.” They drilled and became one of the most productive wells in California. It made Burnham a millionaire. That was in his 60s. Finally, he got his bonanza in his boyhood home. I love the symmetry of that.

He lived to be 86. He died in bed in his sleep which doesn’t seem possible for a man who lived the life that he did from scouts on the frontier to the atomic bomb, but that’s what he did.

Brett McKay: Even in his 70s, we’ll see a brush with death. There was a car accident that he tumbled down a mountain in Hollywood Hills.

Steve Kemper: He was ran off the road and the car was pancake. You couldn’t kill the guy. He just would not die. He survived that like many other things and got married very late in life to his secretary. His wife Blanche died and he married another woman when he was in his early 80s. I think his zest for life did never diminished.

Brett McKay: What was driving Burnham this entire time? Was is it just like this romance or he just had this itch for novelty? Was it money, fame? Why did he put himself in these dangerous areas over and over again?

Steve Kemper: I guess, the cheap, simple explanation, we’d call him an adrenalin junky these days. He had to be where the action was. He wanted to be taking risks. He was drawn to frontiers and places of volatile action. That’s where he thought he felt most the laugh. I remember in his memoir, he talks about coming under gun fire for the first time when he was 10 years old in California. Most of us would think, “I’d prefer not to have anybody shooting at me ever again.” Burnham said, “It was thrilling and it influenced my entire career.” He had that in him since he was a boy.

Also, of course, income. He’s restless. He’s looking for historical action, risks. He’s looking for prospects. He’s looking for money. It just kept his feet on fire. He kept moving until he could find satisfaction in all those different areas.

Brett McKay: I’m curious, Steve, after your researching and writing about Burnham, is there anything about his life that inspired you to change yours a bit, like model your life a little bit after Burnham’s?

Steve Kemper: I’ve been a freelance writer for over 30 years. I have that riskiness, I guess. What this really did was allow me to not only revisit my boyhood, but then to think about it and to think about American history in a much more complicated way than I was able to do when I was 10, and writing on the range in my backyard. Do you know what I mean?

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Steve Kemper: It gave me deep pleasure to read and to write about all these mountain men, the Apaches, the soldiers, the prospectors, and the miners, but then also to bring to it a vast awareness of how these things happened, and why they happened, and which parts of them are appalling, which parts are admirable because it’s all America. It’s how we got where we are. If we don’t understand that, we’re not going to move ahead.

Burnham was against immigration. Look at him, he went to Africa to start over as an immigrant. His ancestors came to America to start over as immigrants. He was against the Mexican immigration after growing up in Los Angeles. It doesn’t make sense. Then, you look at our presidential candidates, two of them were the sons of immigrants, and they were running on an anti-immigration platform.

In America, these things, they keep popping up the racial stuff, the stuff about immigration, the stuff about military might. What should we do and what is our place in the world? It all keeps popping up. It’s very rich, rich material especially if you come to it with some knowledge of what came before.

Brett McKay: You can get that knowledge by reading about the life of Burnham because he lived it all. Steve, this has been a great discussion. Literally, we scratched the surface. As you say, we skipped over parts of his life, his exploits in the Klondike, in Mexico. Where can people find out more about your book and your work?

Steve Kemper: I have a website. It’s www.stevekemper.net. There’s some information about Burnham and the book there. You can read the prologue to the book on the website, or you can go to your local bookstore, or an online bookstore, and you can find the book, and buy it, and read it. I hope that you’ll enjoy it.

Brett McKay: Steve Kemper, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Steve Kemper: It sure has. Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest here was Steve Kemper. He’s the author of the book, A Splendid Savage: The Restless Life of Frederick Russell Burnham. You can find that on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Really, go out and get it. It is a fascinating story. Some of them are unbelievable but they all happened. Go check that on amazon.com. For show notes for the show, after you’re done listening, check out aom.is/kemper.

That wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure you check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed the show and got something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. Help spread the word about the show. As always, I appreciate your keenly support and until next time. This is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.