While it might not seem so at first blush, the history of the bachelor in America is complex and truly fascinating. When colonists first settled America, the bachelor as an identity didn’t even exist. But as time passed, bachelors became one of the driving forces shaping our concept of manliness in America. In fact, many of the popular ideas we have about manliness today (and that we talk about on the site), emerged out of bachelor culture, particularly from the late 19th century.

My guest today on the podcast delved deep into this often overlooked part of history to show that many of the qualms that society has about single men today have in fact existed since the founding of the country. Howard Chudacoff is a professor of history at Brown University and the author of The Age of the Bachelor: Creating an American Subculture. In today’s podcast, Professor Chudacoff and I discuss the evolution of the bachelor throughout American history.

Show Highlights

- Why colonial Americans charged a special tax on bachelors

- The nickname Ben Franklin gave to bachelors

- Why there was an explosion of bachelors beginning in the 19th century

- Why the 19th century was the “Age of the Bachelor”

- What role barbershops, saloons, and pool halls played in the lives of American bachelors

- America’s first, great men’s interest magazine — The National Police Gazette

- John L. Sullivan — King of the Bachelors

- The status of the American bachelor today

- And much more!

If you’re a history buff and a fan of AoM, you’ll certainly enjoy The Age of the Bachelor. It’s filled with great insights on the origins of what a lot of us consider “manly” today.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Special thanks to Keelan O’Hara for editing the podcast!

Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. Whether you are married with kids, divorced, a grandparent with grandchildren, a widower, or an unmarried man, what we all have in common, as men, is that at one point in our lives, we have all been bachelors, that is an unmarried man. It’s funny, we don’t really refer to unmarried men as bachelors anymore. We also don’t talk about unmarried women as spinsters. We’re going to talk about why today. What’s fascinating is that even though all men have been bachelors at one point in their life, there isn’t a lot of history or sociology written about the culture of bachelorhood that grows up around unmarried men because it’s different from the culture of married men or grandparents or divorced men. It’s completely different.

I found a few books and one of my favorite is by Brown history professor Howard Chudacoff. It’s called The Age of the Bachelor: Creating an American Subculture. In it, he explores the history of bachelorhood in America, starting in the colonial days of America, going all the way to the late 20th/early 21st century, but a big portion of the book is dedicated to the culture of bachelorhood that sprung up during the late 19th/early 20th centuries. It was during this time that bachelors, American bachelors, and companies catering towards bachelors created a lot of the culture, a lot of the aesthetic of what we consider old-school manly today, so facial hair, like mustaches and the big beards was big during that time. American bachelors were pushing it.

The barbershop exploded during the late 19th century/early 20th centuries, saloons, billiards halls, gambling became huge and it was all because of American bachelors. Popular men’s magazines first got their start during this time. They were driven by and catered to American bachelors. Sports were huge, particularly boxing, baseball, and football. John L. Sullivan, the bare-knuckle pugilist that is at the top of the Art of Manliness header, he was a huge American celebrity in his time. He was considered the king of the bachelors, even though he wasn’t a bachelor for most of his life, so yeah, a lot of stuff we think of as old-school manly was started by bachelors during this time period. Today on the podcast, Professor Chudacoff and I are going to discuss this golden age of bachelorhood and its influence that we can still feel today on American masculinity. You’re a long-time Art of Manliness reader, you love the whole old-school man thing, you’re really going to enjoy this podcast because you’re going to find out a lot of great insights about where this stuff that you like sprung up and got its start, so without further ado, Professor Chudacoff with The Age of the Bachelor.

Howard Chudacoff, welcome to the show.

Howard Chudacoff: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: Okay, so you published a book a few years ago called The Age of the Bachelor. A few years ago, I did a series of articles on the site about the cultural history of bachelorhood in America and in my research, I was surprised how few books there were on the topic and still are. Yours is one of the few. I think there’s 2 others that I found. Why haven’t historians or anthropologists or sociologists, why haven’t they looked into this subculture of America?

Howard Chudacoff: I don’t know. I can’t speak for them. I guess because they didn’t think that it was a popular enough topic somehow. I think other stages of life have attracted more attention, maybe because people thought they were more consequential, whether it was adolescence or infancy or old age. Of course, bachelorhood is tied up with issues of gender and maleness that you’re interested in. Women’s history and women’s culture, I guess, was far more attractive to a number of historians, so I’m not really sure. I guess those are what answers I can think of.

Brett McKay: Sure. In your book, you call bachelors both a subgroup and a subculture. What’s the difference between the two and how does bachelorhood in America fit those two definitions?

Howard Chudacoff: I’m not an anthropologist, so I’m using these definitions very loosely and these concept, so I probably am open to criticism on that. Culture is often described or defined as a way of life of a group of people, their values, their symbols, their beliefs that they pass on almost automatically from one generation to the next. The subculture of bachelorhood is one that exists within male culture and I guess that I call it a subculture because maybe it does not adopt all of the values of male culture and, therefore, is a subgroup within it. I guess I’m maybe interchanging the terms subgroup and subculture. I don’t recall how often I used the term subgroup, but maybe I did. I can’t remember for sure.

Brett McKay: You raise an interesting point because throughout the book about that bachelorhood is a subculture of male culture and that there was a tension between bachelors and married men. What was that tension? Was it a tension about what it meant to be a man? Were bachelors seen as less of a man?

Howard Chudacoff: Yeah. I think it was not less, behavioral in some ways and that is there’s always pressure on men and women to get married, always has been, historically. That’s been the standard way of going through adulthood, so there’s tension there, not that bachelors were necessarily opposing married males, but especially because most bachelors eventually do get married. As I said in my book, every male is a bachelor for at least some part of his life, but the bachelor subculture has always been associated with a kind of alternative and sometimes oppositional behavior that the more settled and traditional men who are married and raising families sometimes feel is too deviant, too far out, too unacceptable, so the bachelor subculture sometimes pushes the extremes of behavior and in doing so, causes some tensions between the unmarried and the married.

Brett McKay: What was the status of the bachelor in early American history, from colonial times up until the mid-19th century?

Howard Chudacoff: One of the factors, of course, that’s affects bachelorhood probably as much as any, if not more, is the marriage market, that is in many early American communities, there was an excess of men. Going over well into the 19th century, as the country moved westward, a lot of the societies and territories of the United States had large majorities of men, so bachelorhood, in some respects, was the consequence of there just not being enough women to marry, or, at least, to marry in the traditional, legal way. There, of course, lots of stories of men having quasi-marital arrangements with Native Americans or African slaves, but the formal marriage structure was affected by these sex ratios.

Brett McKay: Interesting. During this time, too, if I recall, in early American history, there were taxes sometimes levied against bachelors. They were called bachelor taxes.

Howard Chudacoff: Yeah, right, because in order to have an established community, you need to have established families that are procreating and raising a new generation. Those men who were not married, at least beyond a certain age, were deemed to be not contributing to the community in a way that was desired, so there were taxes levied against them as a means to induce them to marry and penalize them for not being married.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I also think it’s interesting some of the pamphlets and other essays put out by … Some of the Founding Fathers, like Benjamin Franklin, was kind of harsh on bachelors for some reason. He’s really a proponent of the married life. I think he called them rogue elephants, is that correct?

Howard Chudacoff: Yeah, I remember that, yeah, rogue elephants. That really goes back to what I was saying about the supposed deviant behavior of bachelors and especially any kind of wild carousing activities that they might’ve been engaging in, so Benjamin Franklin called them rogue elephants as these outliers of the community.

Brett McKay: Early American history there were probably a lot of bachelors because of the marriage market because men were usually the first ones to arrive to a new territory to settle an area and then the women followed couple years later. It seemed like in the 19th century, in the middle of the 19th century, late 19th century, there was a boom in the number of bachelors. Why did this bachelor boom happen in the mid-19th century?

Howard Chudacoff: The boom in bachelors happened, I think, because marriage was postponed. It wasn’t that there was a big boom in the number proportion of committed bachelors, that is bachelors who never married, but as marriage age rose, and I’m sorry, I don’t have the figures at hand, it meant that men were, and women too, were staying unmarried for a longer period of time than they had been in the past. Now there are several reasons for explaining the rise in the age of marriage. I like to think that it was because there were simply alternatives to marriage, that is there were reasons not to get married because both economically, some men couldn’t afford it and those men who could afford it had diversions that kept them unmarried for a while. Remember, this is beginning of the flowering of community, of consumer culture, and the beginnings of mass entertainment, the beginnings of diversions that men and women could participate in outside of marriage and were accepting and buying into that postponed their marriages for sometimes 2, 3, 4, 5 years.

Brett McKay: Did the influx or the migration to urban areas contribute to that as well?

Howard Chudacoff: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Howard Chudacoff: Yes.

Brett McKay: I think it’s interesting, too, how you talked about people delayed marriage this time and think it’s funny how today, we wring our hands about how young people are putting off marriage longer and longer, but then if you go back to their great-great grandparents, it’s basically about the same age that people are getting married, late 20s. I guess the ’50s and ’60s was an anomaly in American history about marriage age.

Howard Chudacoff: Right. Yeah, today, the average age of marriage is higher than it’s ever been, but of course, the circumstances under which that occurs today are a lot different than the past because there are large numbers of people who live in marital arrangements, but are not formally married as with licenses and vows and everything else that accompanies formal marriage. It’s a little bit difficult to make comparisons between the present and the past because of the circumstances today of married couples, or quasi-married couples, but not formally married couples, and so the age of formal marriage is now much higher than it had been. Now back in the 1950s and ’60s, there was, of course, pressure by society for people to get married and pressure on families to have children and primarily, the circumstance in which children were born then was to a married couple. The sooner that men and women got married, then the sooner that they would begin having children.

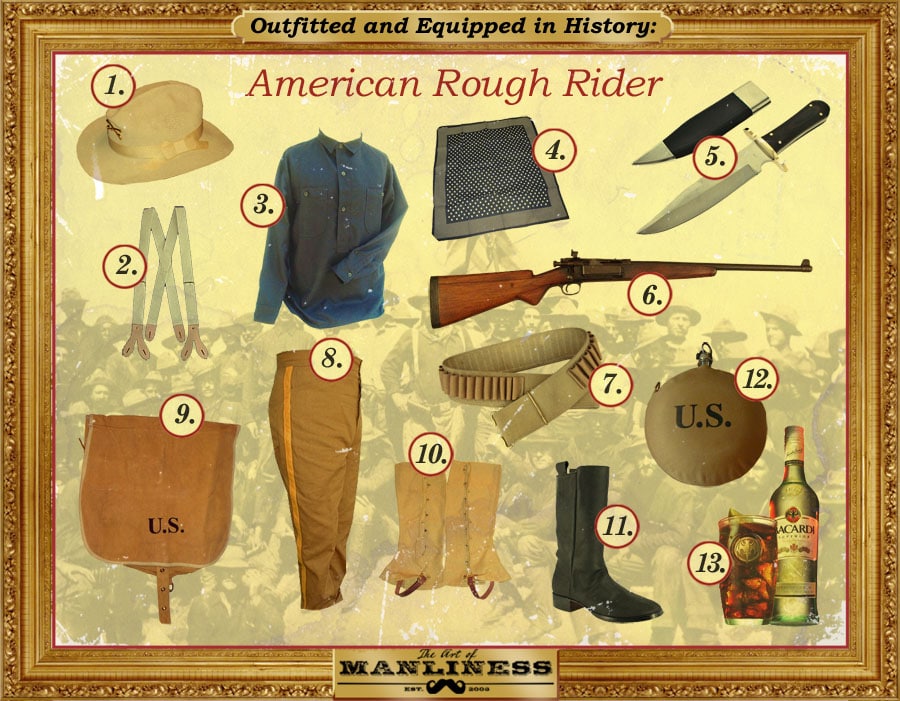

Brett McKay: Let’s go back to the 19th century, so there’s all these things going on. We have a boom in bachelors because people are putting off marriage, an influx of young people to urban centers, urban areas, cities. We have the rise of mass consumerism, the rise of mass entertainment, mass media, and all this brewed together to create the bachelor culture. You call the 19th century the age of the bachelor and as I was reading this, I thought it was interesting that a lot of the things that we consider manly today, right, if you’ve seen our website, we have this vintage aesthetic, it came from this period of time. What were the some of the bachelor institutions that developed during this period that we still see remnants of today?

Howard Chudacoff: Sports, for one thing, the rise of mass sports and the rise of commercial institutions like saloons, barbershops, which barbershops were real hangouts for unmarried men, the boarding house that was the place where bachelors lived when they moved into the cities, and commercial amusements, amusement parks, and then later movie theater, movies, these sorts of things were the establishments that unmarried people patronized quite a lot.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I think you mentioned pool halls, as well, was another …

Howard Chudacoff: Pool halls, yes, right.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I think what’s interesting that all of these, what they have in common, is that, again, going back to that idea that bachelors are somewhat social deviants, right, so it’s saloons, pool halls, where there’s lots of drinking, gambling, smoking going on, these are the institutions. I guess the tension between married men and the rest of society increased between bachelors and them during this period?

Howard Chudacoff: Yeah. My research didn’t focus on getting any hard evidence of that, but there are certainly hints about that, yes.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Going back to sports, too, this was the rise of professional sports and I guess it was primarily bachelors who were participating and watching. Baseball was one and then boxing was the biggest, if I remember correctly.

Howard Chudacoff: I think yeah, boxing and horse racing, have to include that and baseball, yeah. Football was primarily still a college sport then and there weren’t a lot of people in college at the time, so I think it was primarily baseball, boxing, and horse racing.

Brett McKay: Then speaking of boxing, on our website, the unofficial icon is John L. Sullivan. He became, during this period, he was America’s first celebrity, in a lot of ways, and he became the king of the bachelors.

Howard Chudacoff: He was, in the sports world anyway, as a celebrity. Even though he was formally married, he led what many people would call a bachelor’s life of carousing and womanizing and traveling around and brawling and earning and spending money on himself and others instead of developing a family.

Brett McKay: He’s a married man living as a bachelor?

Howard Chudacoff: Yes.

Brett McKay: Yes. Another interesting topic you’ve delved into, which I was aware of this magazine, for some reason, I don’t know, I came across a whole bunch of old copies one time, but the National Police Gazette.

Howard Chudacoff: Oh, yeah.

Brett McKay: It’s a defunct magazine, but at the time, it was considered the bachelor bible. Can you tell us a little bit about the National Police Gazette and the content that young men would find in this magazine?

Howard Chudacoff: I describe the National Police Gazette as a combination of Sports Illustrated, National Enquirer, and Playboy because it focused on all three, as well as True Detective. It started off as an urban publication publishing stories of sensational crimes, abductions and murders and even rapes and these kind of things, but in the back of the newspaper was always sporting news that the publisher, Richard K. Fox expanded over the years. He even himself became a boxing promoter and even promoted some of the fights that John L. Sullivan was involved in, but we had a stormy relationship with Sullivan. Then on some of the inside pages, there were gossip stories or drawings and then later photographs of what were called soubrettes, that I guess we would today call starlets, young, attractive women of the stage whose pictures were published simply to appeal to the prurient interests of men. There were also drawings and illustrations of these crimes against women with these drawings of men trying to abduct women and the women’s clothing falling off their shoulders, but also a lot of stories about women took revenge against men, against cheating husbands and boyfriends and that sort of thing. It was a fascinating publication.

It is very hard to estimate how many men actually read it because its subscription figures don’t tell the whole story. It was delivered weekly to most saloons and pool halls and barbershops in urban areas and therefore, saw it on the table, and men who were just there to hang out or waiting for a haircut would read it, so every issue had multiple readers, most of whom, of course, were men. I’m sure a great proportion of those men were unmarried men, so they were exposed to all these different kinds of exciting stories and sporting news and all of the rest.

Brett McKay: Yeah, Richard K. Fox, he was a savvy businessman the way he promoted that magazine, first with promoting the boxing matches. I think for a while, the National Police Gazette, they were the ones who determined the world champion boxer for a period of time.

Howard Chudacoff: Yes.

Brett McKay: Then distributing the magazine to barbershops because I think he had a section I thought was really interesting, it’s tonsorliorists, is that the word for …

Howard Chudacoff: Yes, it’s the Barber of the Week.

Brett McKay: Yeah, Barber of the Week. I guess that encouraged barbers to subscribe, so they can possibly be the Barber of the Week.

Howard Chudacoff: I think he also, if I remember correctly, I could be wrong, also did the same thing for bartenders.

Brett McKay: That’s correct, he did.

Howard Chudacoff: I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it, yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I’ve seen that, as well.

Howard Chudacoff: Salonkeeper of the Week.

Brett McKay: Yeah, so if you’re listening to this, I think that you can find some facsimiles online. We did a post about it a few years ago, but some of the stories you’re going to find in it, some of them are just outrageous, some of them are just really funny. They had this common series going on about women doing manly things, so they’d have an illustration of a woman wearing pants to church and everyone’s looking scandalized, women smoking, women playing baseball.

Howard Chudacoff: Remember, there also were ads in the publication for male-oriented products both for sexual aids, for playing cards and gambling materials, for tonics of variety sorts, and those sorts of things that were only to be consumed by men.

Brett McKay: It seems like, I guess, things haven’t really changed that much because if you go to the back of most men’s magazines today, you’re going to find advertisements for products that can enhance sexuality or improve virility, same thing happened 150 years ago.

Howard Chudacoff: Yes, that’s right.

Brett McKay: Interesting. What’s the legacy of the age of the bachelor? Did the status of the bachelor change during the early part of the 20th century or did a lot of what began in the 19th century carry over into the early part of the 20th?

Howard Chudacoff: I think it carried over, as I said, and as you suggested yourself, in the immediate post-World War 2 era with the baby boom was, of course, preceded by a marriage boom. There was a lot of social proscription against bachelorhood and encouragement to get married, but by the time you get to the late ’60s and the early ’70s, the notion of the swinging single becomes far more appealing in American society. I attribute it, to some extent anyway, with the rise of the popularity of Playboy, which, of course, replaced the National Police Gazette as the bachelor’s main organ and main publication. Playboy celebrated all of those different qualities of singlehood, of bachelor behavior with wine and women and sports and sexuality and all of the rest that helped to reinforce this swinging single image of men in American society that actually hasn’t really subsided, I don’t think.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Would it be safe to say that in the early part of American history and even up through the 19th century, bachelorhood was something that happened because the marriage market … It wasn’t a choice, oftentimes. Did it slowly and over time become more of a choice, people just decided I’m going to be single and that’s what I’m going to do?

Howard Chudacoff: I want to be single for longer period of time, yes, right.

Brett McKay: What’s the status of the bachelor today? I don’t think I’ve ever heard a man refer to himself as a bachelor, even though …

Howard Chudacoff: No, you don’t. It’s interesting.

Brett McKay: Yeah, why is that? Do we just not identify with that anymore, is it just a word from a bygone era?

Howard Chudacoff: I think it is. I’ve moved on to researching other things, so I haven’t given this much thought and I’m trying to process that myself. There are probably others more qualified to speak about that than I am, but of course, I think it’s because being unmarried has become much more acceptable in American society. Just as you don’t hear the term bachelor used very much, how many times do you hear the word spinster used very much anymore.

Brett McKay: You don’t, so I guess they’ve become pejorative, what’s the word, they’re insults that we don’t use.

Howard Chudacoff: Yeah, that was politically incorrect, I guess, yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah, politically incorrect. Professor Chudacoff, this has been a fascinating discussion. Thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Howard Chudacoff: Thank you very much. I’ve really enjoyed speaking with you and saying hello to your audience.

Brett McKay: Our guest today was Howard Chudacoff. He’s the author of the book The Age of the Bachelor: Creating an American Subculture. If you are a history buff, definitely pick up this book. It’s a fun, fun read and you can find it on amazon.com. That wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com and if you enjoy this podcast, you get something out of it, I’d really appreciate it if you’d go to iTunes or Stitcher, give us a review. Also, please share us with your friends, the more the merrier. Your reviews, your shares, I really appreciate that. Thank you so much. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.